Abstract

The electrocatalytic two-electron oxygen reduction reaction (2e−ORR) for the synthesis of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is an efficient, green, and sustainable technology. However, due to the scaling relationship of the adsorption energy of reaction intermediates, there has long been a trade-off between the activity and selectivity of catalysts, unfavorable in realizing the Sustainable Development Goals. This work comprehensively studies the feasibility of achieving efficient 2e−ORR using pyridine nitrogen-coordinated p-block metal-based single-atom catalyst (SAC) (P@Nx) through density functional theory (DFT) calculations, analyzing its thermodynamic stability, catalytic activity, and H2O2 selectivity. The results show that P@Nx can partially break the scaling relationship between ΔG*OOH and ΔG*O through the transformation of adsorption configurations and the relaxation deformation of the metal–nitrogen (M–N) bonds in the substrate. By regulating the degree of charge transfer, the ΔG*OOH can be tuned into the optimal range for 2e−ORR activity, while maintaining the selectivity descriptor ΔΔG at a low level, thereby enabling a synergistic enhancement in both activity and selectivity. Furthermore, we combine multivariate correlation analysis and multiple linear regression to construct a comprehensive descriptor ϕ based on material property parameters, which quantitatively elucidates the influence weight of material properties on ΔG*OOH. Our work not only screens out P@Nx catalysts with promising application potential but also offers key theoretical insights for the rational design of high-performance p-block metal-based SACs for H2O2 electrosynthesis. It is thereby expected to advance the development of green, sustainable electrochemical synthesis technology and beyond.

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

1. Introduction

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), as an important basic chemical, is widely used in fields such as chemical synthesis, environmental remediation, and bleaching [1–5]. The sustainable production of H2O2 is critical for supporting several United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, including fostering industry innovation, ensuring access to affordable and clean energy, and so on [6]. At present, industrial production of H2O2 primarily depends on the anthraquinone process. However, its multi-step reaction processes and high energy consumption characteristics conflict with the core principles of green chemistry and sustainable development. It is thus necessary for researchers to actively explore greener and more sustainable alternatives [7–9]. The electrochemical two-electron oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) has become a highly promising H2O2 synthesis pathway due to its environmental friendliness and high efficiency [10–12].

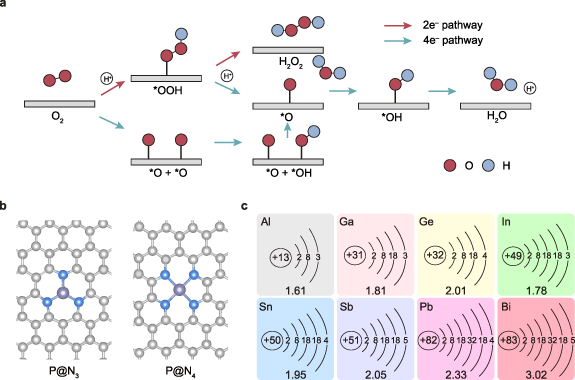

In the electrocatalytic ORR process, there are two competing reaction pathways: the two-electron (2e–) pathway to produce H2O2 (O2 + 2e− + 2 H+ → H2O2) and the four-electron (4e−) pathway to produce H2O (O2 + 4e− + 4 H+ → 2H2O) (figure 1(a)) [5, 13, 14]. To achieve efficient electrochemical synthesis of H2O2, an ideal catalyst should exhibit not only high activity and high selectivity but also excellent stability. From the theory perspective of the adsorption energy of reaction intermediates, strengthening the adsorption of the *OOH intermediate favors improved reaction activity, whereas suppressing the adsorption of its dissociated product *O contributes to enhancing the selectivity toward the 2e−pathway [7, 15, 16]. However, because of the intrinsic scaling relationship between the adsorption energies of key intermediates such as *OOH and *O, simultaneously achieving both high activity and high selectivity remains a significant challenge [17–19].

Figure 1. (a) Reaction pathways along with ORR. (b) Schematic diagrams of P@N3 and P@N4. (c) Valence electron configurations and electronegativities of eight p-block metal atoms.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageSingle-atom catalysts (SACs), featuring well-defined active centers and nearly 100% atomic utilization, offer the possibility to overcome the limitations imposed by the scaling relationship [20]. The coordination environment of the atomically dispersed site can effectively regulate the electronic structure of the central metal atom, thereby optimize the adsorption behavior of intermediates and achieve the ‘dual high’ goal of activity and selectivity [21]. In recent years, p-block metal-based catalysts have gradually attracted great attention in ORR for H2O2 electrosynthesis, owing to the advantages of regulating the adsorption conducts of oxygen-containing species and suppressing unwanted side reactions (such as hydrogen evolution reaction and 4e−ORR) [22]. However, there are still relatively lacking studies on quantitatively analyzing the influence of the coordination interaction between p-block metal single atoms and supports on electrocatalytic performance, as well as the structure-activity relationship between the valence p-orbital electronic configuration and the adsorption energy of intermediates [23, 24]. Therefore, a comprehensively exploration of the catalytic mechanisms and design principles of such catalysts is of great significance for advancing green and sustainable catalytic technologies, such as the synthesis of H2O2 via the 2e−ORR [25, 26].

In this study, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were employed to comprehensively investigate the catalytic performance of SACs which have eight common p-block metals (Al, Ga, Ge, In, Sn, Sb, Pb, Bi) (P@Nx, where P denotes the p-block metal center) been deployed as active centers and pyridine nitrogen as the linkage site for H2O2 synthesis. The stability, selectivity, and activity of two representative coordination configurations, P@N3 and P@N4, were systematically investigated (figure 1(b)). The valence electron structures and electronegativities of these metals are shown in figure 1(c), and the diversity provides an ideal platform for studying the electronic level structure-performance relationship. In addition, we employed multivariate analysis and multiple linear regression methods to uncover the interaction mechanisms between adsorbates and catalysts, establish quantitative descriptors for the intrinsic properties of P@Nx, and elucidate its inherent structure-performance relationship. This work not only screens out P@Nx catalysts with promising application potential but also provides new theoretical methods and design strategies for high-performance H2O2 electrocatalysts.

2. Computational methods

The spin-polarized DFT calculations were performed with the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Program. The exchange and correlation energies were described by generalized gradient approximation in the Perdew–Burke Ernzerhof form. The plane wave base set was used with a cutoff energy of 400 eV. The convergence criteria of energies and forces for structural optimizations were set to 10−5 eV and 0.05 eV Å−1. DFT-D3 method is used to consider Vander Waals interactions. The method of Bader charge calculation was used to analyze the charge transfer properties. A vacuum layer of at least 15 Å was implemented perpendicular to the surface to eliminate artificial interactions between periodic images.

The formation energy (Ef) was calculated using equation (1), where EP@Nx is the energy of P@Nx catalysts, EV-gra is the energy of defective graphene. μC, μN, and μP are the chemical potentials of each C, N and p-block metals, respectively,

We applied the computational hydrogen electrode [27], when calculating the changes of Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of intermediates during ORR. This model defines the free energy of protons and electrons as

The calculated electronic energy is converted into Gibbs free energy by adding zero-point energy and entropy contribution, and U is the applied potential relative to the standard hydrogen electrode. For molecules, translational, rotational, and vibrational entropies are considered, while for adsorbed intermediates, only vibrational entropy is considered, and the contributions of translational and rotational entropies can be neglected. Since the accuracy of DFT calculations for triplet O2 molecules is relatively limited, all free energies were calculated relative to H2O and H2 [28].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Stability and electronic properties of P@Nx

To evaluate the thermodynamic stability of the P@Nx catalyst, we calculated the Ef of embedding a single p-block metal atom after introducing nitrogen doping in graphene. A smaller (more negative) Ef indicates a stronger binding ability between the metal atom and the nitrogen-doped graphene substrate, making it more difficult for the catalyst to agglomerate or detach during the reaction, thus resulting in higher thermodynamic stability.

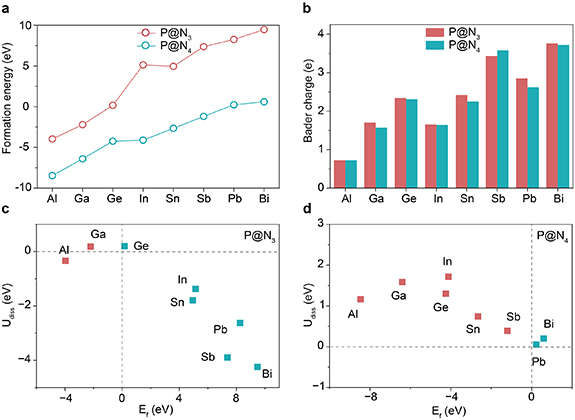

Figure 2(a) shows the Ef values of the P@N3 and P@N4 catalysts examined in this study, with all data arranged according to the increasing atomic number of the central p-block metals. The results show that in both P@N3 and P@N4 configurations, Ef of the system presents a monotonically increasing trend with the increase of the atomic number of p-block metal atoms. This phenomenon can be well explained by the periodic variation law of element properties, within the same period, the electronegativity of p-block metals increases gradually from left to right, while the atomic radius decreases gradually [29, 30]. Specifically, although a smaller atomic radius theoretically promotes stronger orbital overlap, the substantial increase in the electronegativity of the metal atoms reduces the electronegativity difference between them and the pyridinic nitrogen atoms (electronegativity ≈ 3). On the one hand, this weakens the ionic component of the M–N bond, thereby reducing the electrostatic interaction. On the other hand, the increased competitive attraction of the more electronegative metal atoms for the bonding electrons, conversely, weakens the net bonding strength. The combined effect of the two causes a weakening of the overall binding ability between the metal and the nitrogen-doped carbon substrate, which increases the energy required for metal atoms to be embedded into the substrate, manifesting as an increase of Ef toward positive values. When moving across the different periods, although electronegativity decreases, the atomic radius increases significantly. The increased radius leads to a longer bond length between the metal atom and the pyridinic nitrogen in the nitrogen-doped carbon substrate, reducing the efficiency of orbital overlap, and weakening of the covalent component of the bond. Although the decrease of electronegativity may enhance the bonding polarity, the geometric mismatch and increased interaction distance become the dominant factors, which also result in a reducing binding capacity. This observation aligns with the periodic trend in the bonding properties of p-block elements as a function of atomic number [31].

Figure 2. (a) Formation energies of P@Nx. (b) Bader charge values of central atoms in P@Nx. Udiss of (c) P@N3 and (d) P@N4.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageIn addition, by comparing the Ef of the two configurations, the Ef of N4-coordinated SACs is generally more negative than that of N3-coordinated ones. In the N4-coordinated structure, both the Ef of the substrate double-vacancy defect and the steric hindrance during metal atom anchoring are smaller, allowing the atomic spacing to more readily reach the lowest energy state during structural relaxation, ultimately resulting in stronger M–N bond binding [32].

To quantify the charge transfer behavior of the active centers (metal atoms) in P@Nx catalysts and clarify the electronic state characteristics, this study investigated the charge distribution of metal centers in different configurations through Bader charge analysis (figure 2(b)). Because they directly affect the adsorption strength and electron transfer efficiency between the catalyst and reaction intermediates (such as *OOH, *O). The results indicate that in both coordination configurations, the changes in the metal center’s charge strictly follow the group number rule for p-block metals: as the group number increases from Group 13 to Group 15 (corresponding to an increase in the number of outer valence electrons), the net charge of the metal center gradually increases. Moreover, the charge number of all metal centers is lower than that in their elemental state. This is because the pyridine nitrogen atoms have strong electronegativity and will withdraw electrons from the metal centers through coordinate bonds, resulting in partial electron deficiency of the metal atoms. In addition, except for SbN3, the number of electrons at the metal center in all N3-coordination configurations is greater than or equal to that in N4-coordination configurations. This phenomenon is attributed to that N4-coordination has one more electron-withdrawing nitrogen atom than N3. The stronger electron-withdrawing effect further decreases the electron density at the metal center in the N4-coordinated structure [5].

Given that the p-orbitals of p-block metals are usually not fully filled with electrons, they can effectively overlap with the valence orbitals of reaction intermediates (such as the 2p-orbital of oxygen atom). This property enables them to directly participate in the formation and breaking of chemical bonds. In addition, the electron occupancy of p-orbitals and their energy level positions can significantly regulate the adsorption energy of intermediates. Therefore, the electronic structure of the p-orbital ultimately regulates the adsorption behavior and reaction activity of the catalyst [22].

In addition, the dissolution potential (Udiss) reflects the stability of the catalyst in an electrochemical environment. A more positive Udiss indicates that the metal atoms on the studied SACs are sufficiently strongly bound to the support, which can prevent the dissolution of metal atoms under electrochemical conditions. Figures 2(c) and (d) show the relationship between the Udiss and Ef of P@Nx, from which the stability of P@N4 is significantly better than that of P@N3. This is consistent with the previous law of energy formation.

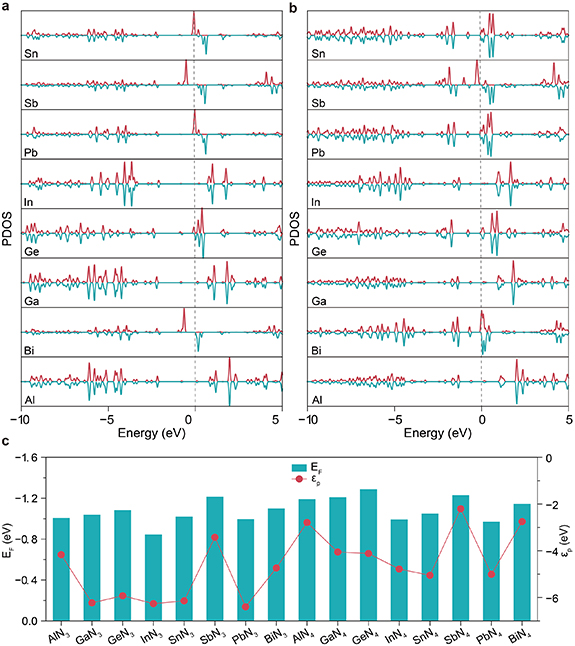

To reveal the influence of Udiss, we employed the projected density of states (PDOS) method to study the electronic structure of the p-orbitals of the metal center. As shown in figures 3(a) and (b) (the PDOS of px-, py-, and pz-orbitals are shown in figures S1–16.), the four metal centers Bi, Pb, Sn, and Sb in the P@N3 configuration exhibit significant spin polarization near the Fermi level (EF). The peak position of the up-spin orbital is below the EF, corresponding to the electron-occupied state; the peak position of the down-spin orbital is above the EF, corresponding to the electron-unoccupied state. This asymmetric distribution of spin orbitals makes the system generate a weak magnetic moment (table S1). The combined effect of the valence p-orbital electrons (2 or 3) of these metals and the orbital splitting induced by the N3 (odd-numbered) coordination environment leads to asymmetric splitting of the metal’s valence p-orbitals. As a result, the orbital electrons cannot be fully paired. The superposition of the spin magnetic moments of the unpaired electrons forms a net magnetic moment of the system. While N4 is an even-numbered coordination, the orbital splitting is symmetric, and electrons can easily achieve full pairing, thus the magnetic moment is weakened or disappears [33]. This phenomenon directly demonstrate that the parity of the number of coordinated nitrogen atoms around the metal center will affect the electron spin distribution and overall electron allocation by regulating the symmetry of orbital splitting, thereby influencing the magnetic moment and activity of the catalyst.

Figure 3. PDOS of the central atom’s p-orbital of (a) P@N3 and (b) P@N4. (c) Fermi levels of P@Nx and p-band centers of their central atoms.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageIn addition, for the four metals Al, Ga, Ge, and In, the peak intensity of the occupied states in the low-energy region of their P@N3 configuration is significantly higher than that of the P@N4 configuration. This result is well consistent with the conclusion of the previous Bader charge analysis, the number of nitrogen atoms coordinated by N3 is less than that by N4. This results in a weaker electron-withdrawing effect, allowing higher electron density to be retained at the metal center. Consequently, more electrons tend to occupy orbitals with lower energy, which ultimately manifests as an increase in the intensity of the occupied-state peaks at lower energy levels.

Figure 3(c) shows the Ef of each system and the position of their p-band center (p) relative to Ef. It can be found that the

p of all P@N3 configurations are significantly lower than those of the P@N4 configurations. It usually means that the metal centers on the P@N3 surface may have a weaker ability to adsorb reaction intermediates, considering that higher

p (closer to the EF) is generally associated with stronger adsorption bonds [34]. However, under the same coordination configuration, the position of the

p does not show an obvious monotonic relationship with the atomic number of the metal. This indicates that, beyond the intrinsic electronic structure determined by the atomic number, factors such as the local geometry of the M–N coordination environment, bond lengths (figures S17 and S18), and specific orbital hybridization modes may collectively determine the final position of

p [35].

3.2. ORR thermodynamic properties of P@Nx

The adsorption behavior of oxygen intermediates (such as *OOH and *O) onto metal active sites is a key factor when determining the catalytic activity and selectivity of the ORR [36]. To comprehensively understand the catalytic performance of P@Nx materials, we first calculated the adsorption free energy of the above intermediates on different P@Nx structures. Based on these energy data and the evaluation criteria established in previous studies, we further estimated the thermodynamic stability, intrinsic activity, and 2e−/4e−pathway selectivity of each catalyst in the ORR [37].

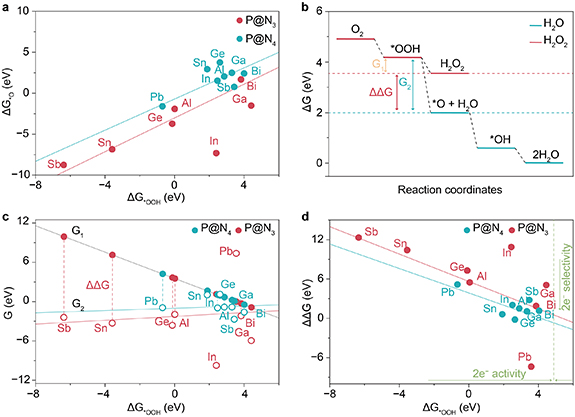

The ORR activity of P@Nx depends on ΔG*OOH in largely. As the adsorption free energy of another key intermediate in the ORR reaction, the correlation characteristics between ΔG*O and ΔG*OOH reflect the synergy of the catalyst in regulating the adsorption of intermediates, which is also an important entry point for understanding the intrinsic P@Nx ORR activity. As shown in figure 4(a), the ΔG*OOH values of all P@N3 and P@N4 configurations are less than 4.2 eV, which indicates that they have a strong adsorption capacity for *OOH. Furthermore, the ΔG*OOH and ΔG*O of some P@Nx materials exhibit a significant linear scaling relationship. This is because the adsorption of both *OOH and *O species on the P@Nx metal center primarily involves the formation of p-block metal–oxygen (P–O) bonds, with their adsorption strengths being uniformly regulated by the electronic structure of the metal center. When the electron density at the metal center decreases, for example, when the electron-withdrawing effect of N4-coordination is enhanced, the binding energy of the P–O bond weakens accordingly. As a result, both ΔG*OOH and ΔG*O increase simultaneously. This behavior forms a linear correlation, which is consistent with the general scaling law of the adsorption energy of ORR intermediates [38]. Therefore, the ΔG*OOH of P@N3 is generally lower than that of P@N4, with a broader distribution range. Some materials deviate from the scaling relationship. This may result from pronounced M–N bond and angle relaxation during *OOH adsorption, which redistributes the electron density on the metal surface and promotes dual-oxygen adsorption (figures S19–22, table S2). This can be supported by the fact that the distortion energy and relaxation energy of P@N4 are mostly higher than those of P@N3 (figure S23). As a result, the change range of *OOH adsorption energy is much larger than that of O, breaking the original linear correlation (figures 4(a) and S24). The linear fit between ΔG*O and ΔG*OOH yields a coefficient of determination (R2) as low as 0.48 (table S3). This phenomenon provides the possibility to improve the selectivity of highly active catalysts.

Figure 4. (a) Scaling relationships between ΔG*OOH and ΔG*O for P@N3 and P@N4. (b) Free energy diagrams for 2e−and 4e−ORR, along with the definitions of G1, G2, and ΔΔG. (c) Functional relationships between G1, G2, and ΔG*OOH. (d) Selectivity plot with ΔΔG as a function of ΔG*OOH.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe ORR selectivity is essentially determined by the two competing reduction reactions of *OOH: the direct reduction of *OOH to H2O2 and its further dissociation into *O. To quantitatively describe this selectivity difference, we use the free energy difference between two competing reactions as the selectivity descriptor (ΔΔG) [39]. Conversely, the 4e−pathway is more likely to occur. It is worth noting that the value of ΔΔG is largely influenced by ΔG*O. The more negative the ΔG*O value (indicating more stable *O adsorption), the easier it becomes for *OOH to dissociate into *O. Consequently, ΔΔG increases, and the selectivity shifts toward the 4e− pathway. The ORR thermodynamic free energy step diagram in figure 4(b) clearly shows the energy change relationship between the 2e−and 4e−pathways, in which two key free energy differences are defined. G1 is the free energy difference between the product H2O2 and the intermediate *OOH in the H2O2 generation pathway, thus reflecting the thermodynamic feasibility of the 2e−pathway. G2 represents the free energy difference between the intermediate *O and *OOH in the 4e−pathway, reflecting the thermodynamic tendency of *OOH dissociation. The selectivity descriptor ΔΔG is calculated by the difference between G1 and G2 (ΔΔG = G1–G2).

The calculation results for all P@Nx catalysts reveal that the variation range of G1 is significantly greater than that of G2. As ΔG*OOH increases toward the optimal energy range for the 2e−ORR (about 4.2 eV), G1 decreases. This leads to a reduction in ΔΔG. Consequently, the catalyst’s selectivity for the 2e—pathway is enhanced, as shown in figure 4(c). The underlying reason for this behavior in P@Nx catalysts is the structural deformation during *OOH adsorption [37]. These structural adjustments break the scaling relationship between the adsorption energies of *OOH and *O. The regulatory effect of structural adjustment on the adsorption strength of *OOH (directly correlated with G1) is much stronger than its impact on the adsorption strength of *O (correlated with G2). As a result, G1 changes more significant. This leads to the observed trend where ΔΔG decreases as ΔG*OOH increases. The P@N4 configuration shows a more pronounced effect. In general, the G2 value of P@N4 is higher than that of P@N3. This is because the N4-coordination environment has greater steric hindrance. Nitrogen atoms also exert a stronger electron-withdrawing effect. These factors strongly influence the adsorption configuration and bonding interactions of *OOH. Thus, P@N4 more effectively breaks the scaling relationship and preferentially tunes *OOH adsorption, leading to improved selectivity.

Figure 4(d) further shows the overall trend of ΔΔG as a function of ΔG*OOH. As ΔG*OOH increases, ΔΔG generally decreases. At the same value of ΔG*OOH, the ΔΔG of P@N4 is lower than that of P@N3. For the 2e−ORR to exhibit optimal activity, ΔG*OOH should be around 4.2 eV. Therefore, tuning the coordination environment of P@Nx or the electronic structure of its metal center to adjust ΔG*OOH to approximately 4.2 eV is a promising strategy. This approach can simultaneously achieve high catalytic activity and enhance 2e−selectivity by reducing ΔΔG. Such a catalyst would be ideal for the efficient synthesis of H2O2.

3.3. Descriptors of key intermediates of ORR on P@Nx

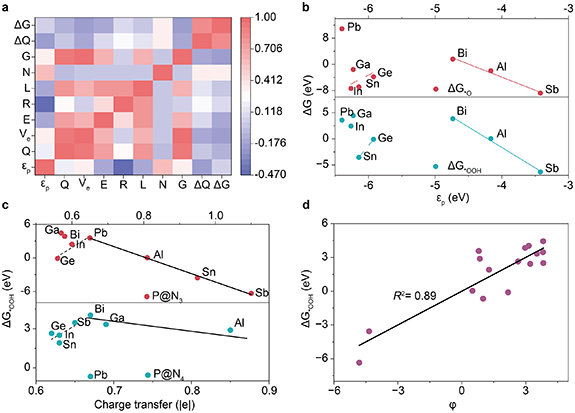

To identify the key factors regulating the adsorption of *OOH on P@Nx catalysts, we selected nine parameters for Pearson correlation analysis. These parameters include the coordination number (N), number of transferred electrons (ΔQ), p-band center of the central atom (p), number of valence electrons (Ve), Bader charge (Q), electronegativity (E), atomic radius (R), period number (L), and group number (G). The main goal was to find a dominant descriptor for ΔG*OOH. This discovery would provide a theoretical basis for the targeted design of P@Nx catalysts.

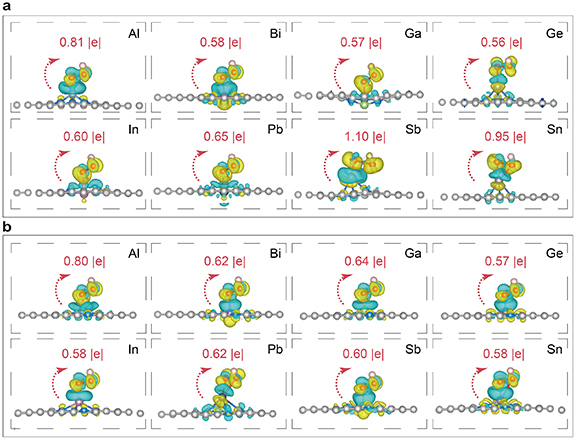

Figure 5 shows the adsorption configuration and electron transfer of the *OOH intermediate on the central atom of P@Nx. The charge density difference diagram reveals an electron transfer mechanism between *OOH and the catalyst. In this process, the occupied orbitals of the p-block metal atom push electrons into the antibonding orbitals of *OOH. This electron donation occurs through the two oxygen atoms. Consequently, the O–O bond becomes significantly activated, which is evidenced by a noticeable elongation of the O–O bond length.

Figure 5. (a) Optimized adsorption configurations and charge density differences of *OOH chemisorbed on (a) P@N3 and (b) P@N4.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 6(a) shows a strong linear correlation between ΔQ and ΔG*OOH. This correlation aligns with the fundamental principle that electron density regulates adsorption energy. Specifically, a greater number of transferred electrons increases the electron density on the metal center. The higher electron density strengthens the bonding interaction in the P–O bond. This results in more stable OOH adsorption and a lower ΔG*OOH value [38]. Our findings are consistent with the general rule that the adsorption strength of intermediates increases with the electron density of the metal center [40]. This consistency confirms that the number of transferred electrons is a valid key parameter for regulating *OOH adsorption.

Figure 6. (a) Pearson correlation coefficients between key properties of P@Nx and ΔG*OOH. (b) Relationships between ΔG*OOH, ΔG*O, and p on P@N3. (c) Relationships between ΔG*OOH and transferred electron numbers on P@N3 and (b) P@N4. (d) Relationship between ΔG*OOH and the newly defined descriptor ϕ.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageAlthough linear correlation analysis indicates a weak overall correlation between p and ΔG*OOH,

p remains a key indicator. It effectively describes the interaction between the valence p-orbitals of the metal and the valence orbitals of adsorbed oxygen. Specifically, when

p moves closer to the EF, the overlap between the metal p-orbitals and the oxygen 2p-orbital increases (figures S25–S29). This enhanced overlap strengthens orbital hybridization. Consequently, the bonding interaction between metal and oxygen becomes stronger, leading to a lower ΔG*OOH [41].

Further analysis by dividing the data into intervals reveals an energy-level-dependent relationship between ΔG*OOH and p (figure 6(b)). In the low

p range (below-5 eV), no significant correlation is observed. Here,

p is far from EF, resulting in minimal orbital overlap. Thus, the adsorption of OOH is dominated by other factors, such as steric hindrance, which masks the effect of

p. In contrast, a clear trend emerges in the higher occupied p-band center range (above-5 eV). As

p approaches EF, orbital hybridization becomes the dominant factor for adsorption. The P–O bond energy increases significantly with enhanced orbital overlap. This ultimately causes ΔG*OOH to decrease markedly as

p rises [41].

We further analyzed the relationship between ΔQ and ΔG*OOH by configuration. When ΔQ exceeds 0.6 |e|, a strong negative linear correlation is observed in the P@N3 configuration. In contrast, the linear relationship is much weaker in the P@N4 configuration (figure 6(c)). This difference likely arises from the higher geometric flexibility of the N4-coordination site. This flexibility allows the system to achieve lower free energy through more pronounced structural relaxation. Consequently, the effect of charge transfer on adsorption energy is partially offset [42].

In the low charge transfer regime (ΔQ < 0.6 |e|), both configurations exhibit a weak positive correlation. This trend suggests that other factors become dominant in this range. Possible factors include electrostatic interactions or steric hindrance. These factors may overshadow the influence of charge transfer on the adsorption energy, leading to the observed weaker overall correlation [37].

In summary, the ΔG*OOH on P@Nx catalysts is regulated by a complex synergy of various intrinsic factors. The influence of each factor varies across different numerical ranges, with some exhibiting clear scaling relationships and periodic patterns. A single descriptor cannot fully demonstrate this complex structure-activity relationship. To overcome this limitation, we employed multiple linear regression model. This model integrates key parameters related to electronic and geometric structures, including p, ΔQ, Ve, E, N, and Q. The goal was to construct a comprehensive predictive descriptor, ϕ. Its mathematical expression is as follows,

In this model, each term quantifies the weight and direction of the contribution made by its corresponding physical parameter to ΔG*OOH. The constant term represents a baseline offset (table S4). Essentially, the model approximates the complex physical process of multi-factor adsorption energy regulation. It does this by linearly superimposing the independent effects of key parameters.

Figure 6(d) shows that this comprehensive descriptor, ϕ, strongly correlates with ΔG*OOH (R2 = 0.89). This excellent correlation indicates that ϕ successfully captures the key physical factors affecting *OOH adsorption and their synergy. Its predictive ability is far superior to any single descriptor, and captures the scaling deviation between ΔG*OOH and ΔG*O (figures S30 and S31, table S3). This result confirms the reliability of the multi-parameter cooperative regulation mechanism. More importantly, the ϕ descriptor provides a powerful theoretical tool. It can be used to efficiently pre-screen new P@Nx catalyst materials with ideal ΔG*OOH values [43].

Guided by these insights, we sought to further optimize the 2e−ORR performance of P@Nx catalysts. We focused on regulating the electronic structure of P@N4-type catalysts, such as Bi@N4, which are already near the high-activity range for 2e−ORR. The core strategy was to reduce the charge transfer, ΔQ, from the central atom to *OOH. As shown in figures S32 and S33, we doped electron-withdrawing groups (O) to tune the electron density of Bi atoms in Bi@N4. This adjustment successfully increased ΔG*OOH into the target range for high 2e−ORR activity. It also maintained a low ΔΔG, thereby ensuring high selectivity. This outcome verifies the effectiveness of our regulation strategy [44]. Such targeted regulation optimizes *OOH adsorption strength while preserving high selectivity, without being affected by the solvent environment or pH conditions (figures S34 and S35). This approach is expected to accelerate the rational design of high-performance 2e−ORR catalysts.

4. Conclusion

This study systematically investigated the ORR performance of P@Nx catalysts using DFT calculations. We analyzed the scaling relationships between the adsorption free energies of key intermediates. The variation patterns of activity and selectivity descriptors for the 2e−ORR pathway were also examined. Our results demonstrate that P@Nx catalysts can partially break the inherent scaling relationship between ΔG*OOH and ΔG*O. This is achieved through transformations in adsorption configuration and relaxation of the substrate M–N bonds and angles. The effect is more pronounced in catalysts with N4-coordination. Furthermore, when ΔG*OOH increases into the optimal range for the 2e−ORR, ΔΔG decreases synchronously. This enables the synergistic optimization of both activity and selectivity. Through multi-parameter correlation analysis and multiple linear regression, we constructed a comprehensive descriptor, ϕ. This descriptor integrates key catalyst property parameters. It quantitatively reveals the regulatory weight of various material properties on the ORR activity, thus providing an effective tool for screening high-potential catalysts. In summary, this work clarifies the core mechanism behind the 2e−ORR performance of P@Nx catalysts. It also offers a theoretical basis for rationally designing high-performance, p-block metal-based SACs for H2O2 electrosynthesis. These findings contribute to the development of green electrochemical synthesis technologies.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the financial support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22306201 to Y Q Z and 22306202 to S J Z), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20231026 to Y Q Z), the Young Scientific and Technological Talents Support Project of Jiangsu Association for Science and Technology (No. JSTJ-2024-414 to S J Z) and Research Project on the Standardization of Tibetan Medicine (No. ZYBZ2025002 to Z Y Wu, C B and S J Z).

Data availability statement

All data from this work is available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no known competing interests in this work.