Abstract

Agro- and food-waste biomass such as oat hull (Oh) or spent coffee ground (SCG) biomass can yield sustainable adsorbents for water treatment. However, adsorbents in powdered form often face constraints in practical applications (column applications due to backpressure, ease of handling and recovery), which can be alleviated with granular adsorbents that may have lower surface area and adsorption capacity. Granular adsorbents were prepared from 50% Oh or SCG, 10% Kaolinite (K), and 40% chitosan (Chi) as binder that offer active site for surface modification. Surface modification via crosslinking and furfuryl-pyridinium (Py) led to adsorbents SCG50-Py and Oh50-Py. These adsorbents were assessed to remove methyl orange (MO; anionic dye) or methylene blue (MB; cationic dye) from water. Materials characterization employed 13C solids NMR and FT-IR spectroscopy, thermogravimetry and solvent swelling (water & cyclohexane). Dye adsorption isotherms employed the Sips isotherm model to characterize the adsorption parameters. The water uptake of SCG50-Py and Oh50-Py was 100%, while the weight increased for Oh50-Py by 16% and SCG50-Py by 8% in cyclohexane. Prior to furfuryl-pyridinium modification, electrostatic forces dominated the adsorption process where either MO or MB dye adsorption occurred. Upon modification, SCG50-Py showed 74 mg g−1 MO and 24 mg g−1 MB dye adsorption capacity, whereas Oh50-Py observed 121 mg g−1 MO and 17 mg g−1 MB dye adsorption capacity. Surface modification via chemical crosslinking favored stable Oh50-based adsorbents, while the Py modification resulted in dual adsorption of anionic and cationic dyes. SCG50-based adsorbents observe higher stability, as compared to Oh50-based adsorbents without crosslinking. Valorization of under-utilized biomass for concerted MO and MB removal was achieved through a facile granulation and surface modification strategy. Future planned kinetic adsorption studies are anticipated to provide mechanistic insight, along with adsorbent reusability studies in laboratory and environmental water sources to further establish the utility of these systems for practical applications.

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

1. Introduction

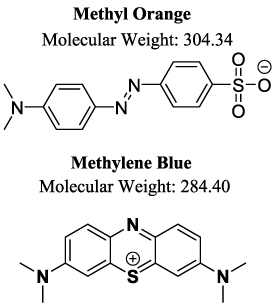

Surface water contamination by dyes occurs through uncontrolled discharge by a variety of industries (e.g. textiles to auto parts) [1, 2]. Approximately 65%–70% of synthetic dyes contain the toxic azo-function, which presents health and environmental hazards, especially in developing nations [3–6]. Commonly employed model dye systems such as methyl orange (MO; anionic) and methylene blue (MB; cationic) have similar molecular weight (see Scheme 1 for the structure of MO and MB dyes) [7–12].

Scheme 1. Molecular structure of methyl orange and methylene blue (without counter ions), including their molecular weight (g mol−1).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageDye removal from aqueous media is accomplished via a variety of advanced methods ranging from biological to chemical methods. Various treatment methods include catalytic or chemical degradation, membrane technology or adsorption with various materials as cost-effective technology [13–18]. The latter methodology has also seen a recent shift into biopolymer-based adsorbent technology for increased sustainability [8, 19–27].

Adsorbents exist in various morphologies, which influence their applicability for filtration and remediation purposes. In contrast to granular pellets, powdered adsorbents generally show higher surface area and site accessibility. Enhanced surface area can favor the adsorption capacity and kinetics of adsorption. However, powdered adsorbents create practical issues in form of high backpressure and column bed cracking, among other handling challenges such as recovery from solution [28]. For practical water treatment applications, granular adsorbents are preferred for fixed bed column applications [29, 30]. Many studies have focused on powdered adsorbents, whereas this study reports on the preparation of granular adsorbents and their potential utility for practical steady state applications. For example, such granular composites comprised of chitosan (Chi), kaolinite (K) and agro-waste biomass have successfully been employed for the remediation of sulfate, methylene blue, and Pb (II) ions [31–33].

Chi is a highly abundant material derived from chitin sourced from crustaceans, fungi, or insects. Glucosamine is one of the co-monomer units of chitosan, where its amine-groups are protonated under acidic conditions [34]. However, Chi is a comparatively costly material, where filler materials are incorporated into such granular composites to reduce the amount of chitosan whilst preserving the adsorption capacity. In turn, Chi may serve as a binder and active site for anionic contaminants within a composite matrix. Also, biomass from agricultural production (e.g. oat hull; Oh) or spent coffee ground (SCG) food waste are low value biomass that can function as filler materials that can be valorized into high value biomass composites. SCG is composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, proteins, lipids, and polyphenols among other constituents. In contrast, Oh is an agricultural biomass by-product, where Saskatchewan holds half of Canada’s oat production. By comparison, kaolinite is a natural clay mineral that functions as a filler and binder via electrostatic interactions within chitosan composites [35].

Herein, the focus was on granular adsorbents that enable practical application due to their unique morphology [36]. The valorization of Oh composites is limited due to its relatively low mechanical strength, especially in aqueous media [37]. In contrast, the incorporation of SCG into granular systems has led to mechanically stable composites in solution. To increase the stability of Oh composites, crosslinking may be employed, which may reduce the adsorption capacity if steric effects influence active site accessibility. Crosslinking under alkaline conditions prevents adsorption of anionic species after neutralization or surface modification. Chemical modification consists of grafting unsaturated cyclic and aromatic moieties in the form of furfuryl and pyridinium onto the backbone of chitosan. This is posited to increase the surface functionalization of the biopolymer to enhance the adsorption of organic dyes from aqueous media. Furfural was selected as it can be derived from a variety of sugars through dehydration [38–45]. Furfural functionalization presents a facile and low-cost strategy of incorporating cationic species on the adsorbent surface, as demonstrated in previous works [46, 47].

Herein, we posit that crosslinking and furfuryl-pyridinium surface modification can yield viable Oh composites for either MO or MB adsorption. The Oh composites are further contrasted with SCG biomass, a common food-waste that is under- utilized. The overall goal of this research was to prepare granular surface modified biocomposite adsorbents for the controlled removal of dyes (MB and MO) at equilibrium conditions. This overall goal is divided into several sub-objectives: (i) preparation of granular composites; (ii) crosslinking and pyridinium surface modification of the composites; and (iii) evaluation of dye adsorption properties at equilibrium conditions. An outcome of this study is to develop a valorization strategy for such under-utilized biomass, and to demonstrate the utility of a unique pyridinium-modified biocomposite adsorbent under steady state conditions for remediation of dye-laden (anionic, cationic) wastewater.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Richardson Milling (Martensville, SK. Canada) provided the Oh. The (SCG; Tchibo Coffee) were collected after brewing, along with drying, and were used as prepared. Low molecular weight chitosan (DDA 82%), kaolinite, FT-IR-grade KBr, epichlorohydrin (ECH; 99%+), methylene blue, and methyl orange were acquired by Sigma Aldrich (Oakville, ON, CA). Glacial acetic acid (99.7%), NaOH (97%), NaHCO3, HCl (aq; 37%) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Ottawa, Canada). Formic acid (98%) and methanol (HPLC grade) was purchased from EMD (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Furfural was acquired from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Ethanol (100%) was sourced from Greenfield Global (Brampton, Canada). Millipore water (18.2 MΩ) was used throughout, and all chemicals were used as received, unless otherwise stated.

2.2. Pellet preparation

2.2.1. Oh50 & SCG50

To obtain granular adsorbents with 50% biomass by dry weight, 10 g of biomass (50%; Oh or SCG) were mixed with 8 g chitosan (40%) and 2 g kaolinite (10%). Approximately 40 ml of 0.2 M acetic acid was added and mixed until a uniform paste was obtained. The paste was spread across small pistol primer trays (S&B; Czech Republic) until all spots were filled and the excess was removed. The pellets were removed after drying for 24 h at 22 °C.

SCG, kaolinite, and chitosan were used as received without further grinding. Particle size ranges (based on dry weight; wt.%) for Chi were 88.6 wt.% between 425 µm and 150 µm, 7.5 wt.% between 150 µm and 125 µm and 3.9 wt.% between 125 µm and 75 µm. For SCG, 20.2 wt.% was > 425 µm, 77.0 wt.% ranged between 425 µm and 150 µm, 2.8 wt.% ranged between 150 µm and 125 µm. K had 70.3 wt.% that ranged between 425 µm and 150 µm, 16.5 wt.% between 150 µm and 125 µm, and 13.1 wt.% between 125 µm and 75 µm. Oh had 65 wt.% that range between 425 µm and 150 µm and 35 wt.% was < 150 µm.

2.2.2. Cross-linked (CL) Oh50-CL & SCG50-CL

The prepared pellets (10 ± 0.1 g) of the prepared, unmodified pellets (same for Oh and SCG pellets), were added to 250 ml 0.5 M NaOH with 1% (2.5 ml) ECH and mildly agitated for 24 h at 22 °C. The pellets were washed multiple times and soaked in Millipore water until a neutral pH was obtained. The pellets were tamped dry via a paper towel to remove excess moisture and employed for the next step without further drying.

2.2.3. Oh50-pyridinium (Oh50-Py) & SCG50-Pyridinium (SCG50-Py)

To obtain pyridinium-modified pellets, 10 ± 0.1 g of the CL pellets (SCG50-CL and Oh50-CL; tamped dry) were added to a 500 ml round bottom flask with condenser and 300 ml 50% ethanol solution was added. 1 ml formic acid and 25 ml furfural were added to the mixture and refluxed for 3 d. Then, the pellets were neutralized first in sodium bicarbonate solution and further washed until a neutral pH was reached by washing with copious amounts of water. Next, the pellets (Oh50-Pyridinium; SCG50-Pyridinium) were dried for 48 h at 22 °C.

To enable comparison for NMR and thermogravimetry analysis (TGA) studies only, only, 6-8 pellets (Oh and SCG) were combined with the same concentration ratio together with furfural and HCOOH, which sat for 3 d without heat and similarly washed (Oh50-Fu; SCG-Fu).

2.3. Characterization

2.3.1. 13C solid state NMR spectroscopy

13C solids NMR spectra were obtained with a 4 mm DOTY cross polarization with magic angle spinning (CP-MAS) probe with a Bruker AVANCE III HD spectrometer operating at 125.77 MHz (1H frequency at 500.13 MHz). The 13C spectra under CP with total suppression of spinning sidebands (CP/TOSS) were obtained at a sample spinning speed of 7.5 kHz, a 1H 90° pulse (5 µs), and contact time (2.0 ms) with a ramp pulse on the 1H channel. Spectral acquisition required 2500 scans with a 1 s recycle delay, along with a 50 kHz SPINAL-64 decoupling sequence. 13C NMR chemical shifts were referenced to adamantane at 38.48 ppm (low field signal).

2.3.2. Thermogravimetry analysis (TGA)

The weight loss profiles were obtained with a Q50 TA Instruments thermogravimetry analyzer (TA Instruments, USA). The samples were placed in an open aluminum pan under N2 atmosphere, equilibrated at 30 °C for 1 min and then heated to 500 °C at a fixed rate (10 °C min-1).

2.4. Hardness tests

Pellet hardness was measured in Newton (N) in the hydrated state via compression testing with a Mark-10 force test stand, ESM 1500LC (based on ASTM D613-14) where the pellets were evaluated while on their side. A 500 N load cell with Mark-10 Model 51 force indicator was used. Pellets were soaked for 1 d in Millipore water and the test conducted in triplicate.

2.5. Adsorption experiments

Adsorption isotherms were performed by adding one pellet (30 ± 1 mg) in a 4-dram vial (10 ml dye solution) at ambient pH (6.8 for MB and 6.2 for MO). Samples were shaken overnight at 22 °C on a rotary shaker (L.E.D. Orbital Shaker, Lab-Line Instruments, Melrose Park, USA). Adsorption isotherms were analyzed via the Sips isotherm model (see equation (1)) due to its utility for describing Langmuir and Freundlich adsorption behavior:

Qm represents the maximum monolayer adsorption capacity, while Ka represents the equilibrium adsorption constant. Ceq is the equilibrium concentration in solution, while n stands for the heterogeneity factor, and qe is the equilibrium adsorption capacity (mg g−1), according to equation (2):

Co represents the initial dye concentration at t = 0, Ce is the residual dye concentration in water at equilibrium after adsorption, m is the weight of the adsorbent and V is the volume. Duplicate adsorption isotherm experiments were conducted, where the error was estimated via standard deviation. For the sorption of liquids (water and cyclohexane), the uptake was determined after soaking for 24 h at 22 °C by subtracting the initial dry weight (in triplicates) from the final weight (tamped dry of residual liquid).

2.6. Regeneration experiments

To evaluate adsorbent regeneration of SCG50-Py and Oh50-Py for MO and MB removal, 1 pellet was submerged in 100 mg l−1 dye and the adsorption capacity was determined by equation (2). After the adsorption experiment (triplicate), the respective pellets were submerged in a solution (1 M NaCl for MO, methanol for MB) and shaken for 4 h. The pellets were rinsed with Millipore water and submerged in the respective dye solutions for 16–18 h for the next cycle.

3. Results and discussion

Herein, the characterization of the granular adsorbents was performed via 13C solids NMR spectroscopy and thermogravimetry. Structural characterization included the precursor systems (non-modified, furfuryl-modified without pyridinium content) for comparison with the composites. The adsorption properties were investigated via solvent swelling (water, cyclohexane) and isotherm equilibrium adsorption profiles with MO and MB dyes. Herein, the focus was on the incorporation of the furfuryl-pyridinium-moieties, where a more detailed characterization was reported earlier [32, 47].

3.1. Characterization

3.1.1. Solids NMR spectroscopy

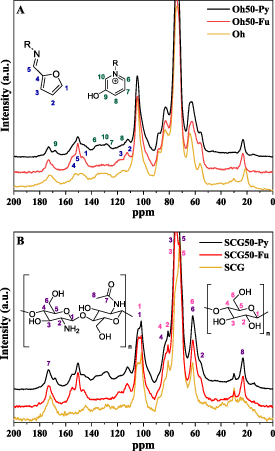

13C solids NMR spectral results provide structural insight on the short-range order and local environment of the 13C nuclei of carbonaceous materials. The effect of pyridinium-modification is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. 13C solids CP-TOSS (cross-polarization total sideband suppression) NMR spectra of the raw materials (Oh (A), SCG(B)) and pyridinium-modified pellets (Oh50-Pyridinium (A), SCG50-Pyridinium (B)) and furfural-modified pellets for comparison to estimate the conversion of furfuryl- to pyridinium moieties (Oh50-Furfuryl (A), SCG50-Furfuryl (B)). Simplified structures of pyridinium- and furfuryl moieties as well as simplified chitosan (50% deacetylated) and cellulose structures for peak assignment included.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageIn both cases, the polysaccharide fingerprint region covers the 60–110 ppm region, while signatures around 20–30 ppm and 175 ppm stem from the acetyl group of chitosan [32]. SCG without modification shows signals between 160–115 ppm and near 170 ppm, ascribed to components such as lignin, tannins, etc [48, 49]. To assign 13C signatures attributed to pyridinium modification and ligneous constituents in Oh/SCG composites, we compared imine-linked Oh50-Furfuryl/SCG50-Furfuryl and pyridinium-modified systems, along with SCG50-pyridinium and Oh50-Pyridinium samples. As noted in figure 1, aromatic and ligneous signatures occur between 120–160 ppm in Oh (A) and SCG (B). This fraction is removed upon washing in NaOH (aq) and subsequent crosslinking, whereas the signals between 145–160 ppm indicate an imine-linked furfuryl moiety. Additional signals near 135 ppm in both figure 1(A) and 1(B) reveal incomplete conversion (ca. 20%–30%) into pyridinium moieties incorporated into both structures with significant furfuryl-content, according to 13C NMR estimates. However, it should be noted that this is a provisional estimate due to the nature of the experimental conditions.

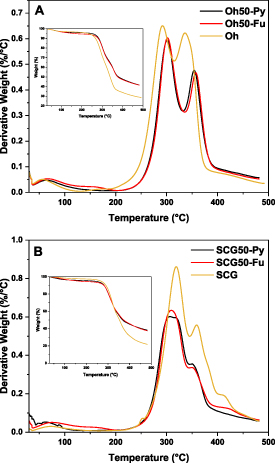

3.1.2. TGA

TGA and the resulting decomposition profiles enable the study of structural changes within composite materials at variable temperature, as evidenced in figure 2. In figure 2(A), pristine Oh observes a distinct decomposition event (maximum 280 °C) which overlaps with a second decomposition event (maximum 340 °C). The first event with an onset above 200 °C can be ascribed to hemicellulose, while the second decomposition event was assigned to cellulose [50]. Furfuryl- and pyridinium modification appears to slightly shift the decomposition events to higher temperatures, which can be attributed to introduction of arene or unsaturated moieties with double-bond functionality versus the role of ECH-crosslinking [32]. On the other hand (figure 2(B)), SCG reveals its first decomposition event near 330 °C (360 °C and 410 °C for the maximum of the second and third event). This indicated the presence of hemicellulose, cellulose, and arene/ligneous compounds with increased thermal stability [49, 51]. The absence or decrease of the event around 410 °C in the modified composites indicates removal of lignin via the NaOH-washing step during the crosslinking step. Crosslinking did not yield any notable increase to the thermal stability of the composite materials, as compared to the unmodified SCG50 or SCG50-Fu. The aromatic and imine-linked moieties (pyridinium, furfuryl) may be inferred through presence of the second event (with an event near 360 °C) for the composites, as compared to non-modified composites, which concurs with results from a previous study [32].

Figure 2. DTG (differential thermogravimetry) profiles of oat hulls, pyridinium modified oat hull composites and furfuryl-modified Oh-composites for comparison: (A), spent coffee grounds, pyridinium modified SCG-composites and as comparison, furfuryl-modified SCG-composites (B).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image3.2. Adsorption experiments

3.2.1. Solvent swelling

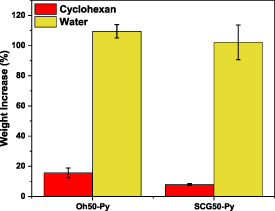

The solvent uptake evidenced by a weight increase of both cyclohexane and water for both granular systems gave information about the hydrophile–lipophile balance of these adsorbents. The relative solvent uptake was evaluated and compared to the dry weight of the pellets (see figure 3).

Figure 3. Comparison of the water and cyclohexane uptake via weight increase (%) of the granular adsorbents intended for the adsorption experiments, as referenced to the dry wt. of adsorbent.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe cyclohexane uptake is less than 16% compared to doubling the weight of both pellet systems through sorption-based water uptake. Thus, both composites are similarly polar, whereas Oh50-Py also shows slightly greater apolar character, as evidenced by greater cyclohexane uptake. This may be due to a reduced accessibility of the arene-moieties in SCG50-Py, in conjunction with potentially lower pyridinium-content (see figure 1).

3.2.2. Dye adsorption studies

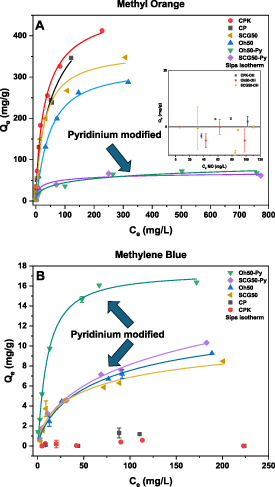

Chitosan as a binder and crucial component in all pellet systems requires acetic acid to facilitate its dissolution in water via protonation to enable formation of the pelletized adsorbents. In turn, protonated amino sites can adsorb MO via electrostatic interactions. In turn, neutralization via NaOH during the surface modification and crosslinking results in deprotonation, which favors MB adsorption. The role of the synthetic conditions on the dye adsorption properties was investigated. A comparison with controls (non-neutralized and only NaOH-washed granular adsorbents with and without waste biomass) is illustrated in figure 4.

Figure 4. Sips adsorption isotherms for (A) MO adsorption (mg g−1) with CP and CPK with no NaOH or surface treatment (30 ± 1 mg pellet in a 10 ml MO solution, pH 6.2). This is compared with the inset showing neutralized pellet systems (CPK-OH, Oh50-OH, SCG50-OH without furfuryl-pyridinium modification); and (B) MO adsorption of waste-based pellet systems with CP, CPK, SCG50, and Oh50 (non-neutralized) as a comparison (30 ± 1 mg pellet in a 10 ml MB solution, pH 6.8). Error bars not visible for cases when the error is smaller than the data point symbols.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe Sips isotherm model (also known as Langmuir–Freundlich hybrid model) was chosen to investigate the dye adsorption properties. The Sips model combines features of the Freundlich and Langmuir models that serve to address the limitations of either respective model. The Freundlich isotherm model is valid at low concentration, which reveals a continual rise in adsorbed quantity at high concentrations and accounts for multilayer adsorption onto heterogeneous sites. In contrast, the Langmuir model assumes adsorption onto homogeneous sites of constant energy in a monolayer profile. The Sips isotherm combines features of both isotherm models whilst accounting for a breadth of adsorption properties. The case for the heterogeneity factor (n) that equals 1, the Sips isotherm converges to the Langmuir model behavior for the case of monolayer adsorption onto homogeneous sites [52, 53].

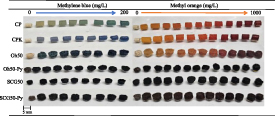

The neutralized (OH) pellet systems chitosan-kaolinite pellets (CPK-OH), Oh50-OH, and SCG50-OH do not show any notable MO uptake. Similarly, protonation with acetic acid attenuates the MB uptake of CP and CPK (cf. table 3 for the adsorption capacities all pellet systems with MO). Refer to figure 5 for a visual comparison of selected pellet systems after MO and MB adsorption. With reference to the influence of NaOH-washing (neutralization in 0.5 M NaOH), a previous report revealed a maximum adsorption capacity towards MB of 54 mg g−1 and 83 mg g−1 for SCG40 and SCG60, and 32 mg g−1 and 34 mg g−1 for Oh40 and Oh60 were reached [32]. We posit that electrostatic interactions govern the binding mechanism for MO uptake. By comparison, MB shows binding affinity toward ligneous and arene components in Oh and SCG result in minor uptake through H-bonding and cation-π interactions. Visual comparison of the pellet systems prior to and after exposure to dye solutions with variable concentration reveal that variable swelling effects of the granular composites occur after 24 h of immersion. As well, we observe a relative color change based on the relative dye uptake for each dye concentration. A notable feature is the cracking and loss of shape of the unmodified Oh50 systems during the adsorption process, as compared to other granules (cf. Figure 5). A previous study of the mechanical properties of granules evaluated the hardness (N) of CL and non- CL Oh and SCG adsorbents without pyridinium modification. The assumption is that pyridinium-modification does not appreciably increase the hardness or the Young’s moduli. Further, it is assumed that the values for the surface modified pellet systems are intermediate to that of the reported adsorbents in table 1 [37]. An appreciable difference relates to lower levels of NaOH (0.5 M) for the preparation of the CL adsorbents herein.

Figure 5. A visual comparison of the adsorption of MO and MB dyes onto SCG50-Py and Oh50-Py pellet systems with pure chitosan (CP) without K, CPK (10% K, 90% Chi), SCG50 and Oh50 (no modification) as comparison. The left most pellet without dye in its dry state is denoted by ‘0’. The arrow denotes incremental dye concentration, where images of the pellets were recorded after collection of the isotherm data (section 2.4).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 1. Hardness (N) for dried granular adsorbents and Young’s moduli (MPa) of cross linked (-CL) and non-cross linked Oh and SCG pellets (40% and 60% waste biomass content) in both hydrated and the dry state. Adapted from an external study [37].

| Hardness (N) | Young’s modulus (dry; MPa) | Young’s modulus (hydrated; MPa) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPK | 100 ± 13 | 629 ± 29 | 86 ± 8 |

| SCG40 | 99 ± 19 | 779 ± 31 | 26 ± 3 |

| SCG40-CL | 120 ± 9 | 954 ± 47 | 87 ± 9 |

| SCG60 | 93 ± 15 | 674 ± 39 | 25 ± 3 |

| SCG60-CL | 124 ± 35 | 348 ± 26 | 37 ± 3 |

| Oh40 | 30 ± 10 | 597 ± 33 | 67 ± 6 |

| Oh40-CL | 58 ± 21 | 748 ± 46 | 236 ± 16 |

| Oh60 | 19 ± 5 | 344 ± 30 | 11 ± 1 |

| Oh60-CL | 58 ± 21 | 519 ± 27 | 201 ± 11 |

A brief confirmation of the applicability of the hardness estimates from table 1 to this study are evidenced by SCG50-Py as the selected material, which yielded a hardness of 123 N ± 33 N. The trend is comparable to SCG60-CL (124 N ± 35 N) and validates the assumption that the hardness values in table 1 can be extrapolated to pyridinium-modified pellets. In general, crosslinking was required to prepare stable and durable Oh-derived pellets, while SCG-derived adsorbents did not benefit from crosslinking. Without crosslinking, the hardness of Oh-derived pellets was at a maximum value of 76 N (20% Oh content). The hardness decreased with greater Oh-content, whereas pellets with 80% Oh-content were unstable in water. The role of hydration and shear stress in water may affect these adsorbents in differently than their hardness properties in the dry state. Hence, the hardness was measured for pellets in the wet state due to the relevant application of the pellets in aqueous media, where such stability counts (see table 2).

Table 2. Hardness (N) for wet granular adsorbent systems (after 24 h water immersion) used in this experiment with focus on CP, CPK, Oh50 and SCG50 for non-cross-linked systems in contrast to Oh50-Py and SCG50-Py after both crosslinking and pyridinium modification.

| Adsorbent | Hardness (N) |

|---|---|

| CP | 13.9 ± 0.5 |

| CPK | 11.1 ± 0.5 |

| Oh50 | 2.5 ± 0.8 |

| Oh50-Py | 10.5 ± 3.3 |

| SCG50 | 11.5 ± 1.8 |

| SCG50-Py | 16.7 ± 3.7 |

As indicated, Oh-based pellets observe the lowest hardness in their hydrated state with ca. 2.5 N, whereas crosslinking increased their hardness to ca. 10.5 N (hydrated). In contrast, SCG50-Py shows a hardness of 16.7 N in contrast to 11.5 N for SCG50 in the hydrated state, which exceed the hardness of Oh-based composites. This trend supports that Oh-based adsorbents require crosslinking for increased stability in solution, further necessitating the role of surface modification to enhance dye adsorption towards MO and MB.

These trends suggest that future research requires a more comprehensive study of the mechanical properties under variable (dry vs. wet) conditions to establish the utility of these adsorbents for practical applications.

In general, while CPK showed an adsorption capacity with MO of 485 mg g−1 (similar to CP), unmodified agro- and food-waste-based pellet systems (Oh50 and SCG50) with 40% chitosan content showed 324 mg g−1 and 364 mg g−1 uptake (table 3). By contrast, the pyridinium-modified pellet systems showed similar dye uptake (comparable within the margin of error) between 74–121 mg g−1 at equilibrium. A heterogeneity factor (n ∼ 1) is noted for the unmodified pellet systems, whereas a lower value (n = 0.5) is noted for SCG50-Py and Oh50-Py is indicative of their heterogeneous adsorption sites.

By contrast, markedly lower adsorption capacities were observed for MB (see table 4) as compared with MO. While positive charges were crucial in enabling MO uptake, MB was not favorably adsorbed onto these pellet systems. MB uptake was contingent on neutralization to avoid electrostatic repulsion, indicating that electrostatic interactions govern the adsorption process for non-modified pellet systems.

Table 3. Methyl Orange adsorption capacities (mg g−1) based on the Sips isotherm model for several biomass pellet systems. A comparison of chitosan-based pellets as control systems (CP, CPK; CPK-OH, Oh50-OH, SCG50-OH; pH 7) is provided.

| Methyl orange | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| qe (mg g−1) | n | K | R2 | |

| CP | 602 ± 154 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.990 95 |

| CPK | 485 ± 20 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.998 07 |

| CPK-OH | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Oh50 | 324 ± 11 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.998 00 |

| Oh50-OH | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Oh50-Py | 121 ± 66 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.003 ± 0.01 | 0.967 73 |

| SCG50 | 364 ± 22 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.990 95 |

| SCG50-OH | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| SCG50-Py | 74 ± 15 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.04 ± 0.04 | 0.956 79 |

NA = No Adsorption

Table 4. Methylene blue adsorption capacities in mg g−1 (Sips isotherm model) for several biomass-based pellet systems, as compared to chitosan-based pellet systems (CP, CPK; pH 7) without biomass.

| Methylene blue | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qe (mg g−1) | n | K | R2 | |

| CP | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| CPK | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Oh50 | 14.0 ± 2.6 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.994 67 |

| Oh50-Py | 17.4 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.97 ± 0.01 | 0.995 50 |

| SCG50 | 12.1 ± 7.0 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.01 ± 0.03 | 0.939 97 |

| SCG50-Py | 24.4 ± 11.7 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.993 30 |

NA = No Adsorption

Although the adsorption capacities are an order of magnitude lower for MB vs. MO, the pyridinium-modified Oh50-Py system show measureable improvement over the unmodified systems (K-value ∼1; high adsorption capacity at low concentrations). Also, while Oh and SCG enable MB dye adsorption, SCG50-Py present a heterogeneity factor of 0.6 in contrast to Oh50-Py (∼1). This trend indicates the role of homogeneous adsorption sites, which are contrasted with the heterogeneous adsorption sites of SCG-derived adsorbents.

For SCG50-Py, the furfuryl-pyridinium modification slightly enhances the uptake of MB, while enabling appreciable MO dye uptake after NaOH-washing and crosslinking. However, SCG50 without any treatment can drastically exceed MO uptake, while still exhibiting MB adsorption. For Oh50-Py, the modification enhances the MB uptake capacity compared to Oh50, which also affords comparable MO uptake (cf. Table 5 for a survey of the literature).

Table 5. Comparison of the individual MB and MO adsorption capacity of SCG50-Py and Oh50-Py with different adsorbents from the literature and various adsorption models ranging from Langmuir (L), Freundlich (F), Temkin, Redlich–Peterson (R–P), to the Sips (S) isotherms.

| Adsorbent | Material | Models | MO | MB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | Type | qe (mg g−1) | qe (mg g−1) | |

| Oh50-Py (this study) | Pellet | Sips | 121 | 17.4 |

| SCG50-Py (this study) | Pellet | Sips | 74 | 24.4 |

| Biochar[55] | Powder | L, F, T | 220 | 91 |

| Activated carbon[22] | Powder | L, F, T | 33 | 38 |

| Nano-fiber-pads[56] | Pads | L, F, S, R–P | 519 | 352 |

| Tire (pyrolyzed)[57] | Powder | L, F | 264 | 278 |

| Poly(aniline-co-metanilic acid)[58] | Powder | L, F | 588 | 345 |

| Activated carbon[59] | Powder | F, L, T, R–P | 287 | 816 |

| Ag/Cu nanoparticles[60] | Powder | L, F | 192 | 374 |

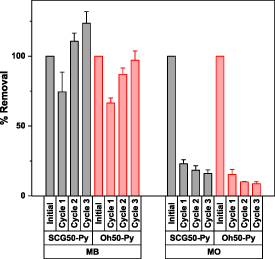

Notably, while most adsorbents (except the nano-fiber-pads) are in powdered form, SCG50-Py and Oh50-Py are in granular form. Hence, lower adsorption capacities are expected for granular systems, while also providing an option for research under dynamic (column) conditions by offsetting backpressure and other concerns. Yetgin and Amlani45 reported the effect of granular vs. powdered adsorbents for powdered and washed (but otherwise non-modified) wheat hulls, rice hulls, and garlic stalks for the uptake of MB. The corresponding uptake capacities between 55–370 mg g−1 were reported (lowest for rice hull, highest for garlic stalk) [54]. As a further point of comparison, Gaber et al investigated methylene blue removal via palm peat (particle size range 1–8 mm) and noted MB removal at 24.5 mg g−1 with an initial concentration of ca. 35 mg l−1 [10]. Additionally, considering the inherently low stability in the wet state of Oh50 compared with Oh50-Py, SCG50 and SCG50-Py, chemical modification (crosslinking and pyridinium modification) is necessary to develop Oh-composites for practical applications in environmental remediation. For regeneration experiments, regenerant screening with methanol and 1 M NaCl solution revealed that more MO was desorbed in 1 M NaCl compared to MeOH. This trend is in contrast to MB regeneration, which showed more desorbed dye in MeOH solution than 1 M NaCl. Subsequently, MeOH was selected for MB and 1 M NaCl selected for MO (see figure 6).

Figure 6. Relative removal efficiency of both pellet systems (SCG50-Py, Oh50-Py) with MO and MB dye systems over 3 cycles.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageWhile MB appears to have reasonable regeneration capabilities over 3 cycles for SCG-Py, the removal efficiency drops to ca. 70% compared to the initial removal for Oh50-Py prior to resuming to the original value. In contrast, both pellet systems dropped to 10% of the initial removal of MO after the third cycle. To enable improved regeneration, the solvent regenerant and time sequence of the process require additional optimization.

As noted above, the focus of this study was on the role of the pyridinium-modification of the pellet surface, the conducted isotherm studies are limited based on the overall insight into the adsorption process. Further insight about the adsorption process is envisaged through a systematic study directed toward the dye adsorption kinetics. Future dynamic adsorption studies are anticipated to support practical field applications, evaluation of the adsorbent performance, and potential for improved adsorbent regeneration.

3.2.3. Summary cost-benefit analysis

The granular adsorbents prepared herein were crosslinked to obtain more stable pellets for greater utility in practical column-based applications, in contrast to powdered adsorbents. Based on the raw material inputs outlined in a previous study [32], a cursory cost-benefit analysis is summarized in table 6.

Table 6. Approximate cost-benefit analysis based on raw material inputs for prices per kg (large quantity orders) in USD and maximum equilibrium adsorption capacity. This analysis excludes water or production costs. The price for SCG and Oh were assumed to be similar (US$ 0.15 kg) and based mostly on transport costs [32].

| MO | MB | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | US$/kg | g dye/US$ | |

| SCG50-Py | 13.14 | 5.63 | 1.32 |

| Oh50-Py | 9.21 | 1.86 | |

By contrast, CPK costs approx. US$30 per kg adsorbent for chemical inputs without further modification, [32] whereas agro- and food-biomass incorporation drastically reduce the cost for the adsorbent preparation. Looking forward, we recommend that future studies assess the role of adsorbent regeneration and re-use to evaluate the adsorbent and the operational costs. Although 20 g batches are feasible for pellet preparation via the suggested methodology, 10 g batch size are favored to enable uniform paste consistency. However, scale-up and modified methodology for extrusion seems feasible for large batch systems. In turn, the chemical surface modification herein relies on widely available industrial chemicals (NaOH, EtOH, furfural, epichlorohydrin, formic acid), where further process optimization is possible.

4. Conclusion

This study reports the preparation of granular adsorbents with Oh and SCG biomass via crosslinking and surface modified biomass (Oh50-Py and SCG50-Py) via pyridinium-moiety incorporation. Partial conversion of furfuryl- into pyridinium moieties for both SCG50-Py and Oh50-Py systems (20%–30%) occurred. Solvent swelling with cyclohexane solvent showed a wt. increase of 8% for SCG50-Py and 16% wt. increase for Oh50-Py. By contrast, a wt. increase of ca. 110% (Oh50-Py) and 102% (SCG50-Py) were observed. This trend relates to a lower pyridinium-content when compared to SCG50-Py or lower arene-site accessibility, which may enable greater uptake of apolar substances from water.

In contrast to SCG-based adsorbents, Oh-based pellet systems are generally unstable in the wet state and require crosslinking for stability. However, unmodified pellets observe only MO uptake, whereas modified/neutralized pellets only show MB uptake. The introduction of the pyridinium moiety enables dual adsorption of MB and MO. Oh50-Py revealed an uptake capacity of 121 mg g−1 for MO and 17 mg g−1 for MB. SCG50-Py reveals 74 mg g−1 MO and 24 mg g−1 MB dye uptake, respectively.

Thus, the benefit of the pyridinium-modification enables pH independent adsorption of anionic dyes such as MO. We demonstrate a sustainable route for biomass valorization as part of the design of biocomposite adsorbents that compare favorably to conventional powdered materials. Future research that improves the conversion of furfuryl-into pyridinium moieties may serve to address the optimization of the adsorption capacity for MB reported herein. Also, future mechanistic studies that build upon this work by employing dye kinetics, dynamic column systems, and adsorbent regeneration in synthetic and real water will contribute to the development of these granular systems for advanced water treatment technology.

Acknowledgment

LDW acknowledges the support provided by the Government of Canada through the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC Discovery Grant Number: RGPIN 04315-2021). Dr Mariam Mir is acknowledged for conducting the solvent swelling tests. The authors acknowledge that this work was conducted in Treaty 6 Territory and the Homeland of the Métis. We pay our respect to the First Nations and Métis ancestors of this place and reaffirm our relationship with one another.

Data availability statement

All data that support the findings of this study are included within the article (and any supplementary information files).