Abstract

The development of non-flammable, non-volatile electrolytes is important for safer lithium and sodium batteries, to facilitate our transition to a net zero economy, but the reliance on fluorine-containing anions brings significant environmental concerns. Here, acesulfamate based ionic liquids (ILs), sodium acesulfamate (Na[ace]) and lithium acesulfamate (Li[ace]) are introduced as promising new fluorine free materials as a more sustainable alternative to the perfluorinated anions (BF4, PF6, FSI and TFSI) currently utilised in energy storage devices. The resulting ammonium, phosphonium and pyrrolidinium acesulfame ILs showed promising physicochemical properties with a relative high conductivity (e.g. 1.4 × 10−4 S cm−1 at 30 °C for [N1222][ace]) and a wide electrochemical stability window (∼4 V). Lithium and sodium acesulfamate salts were synthesised from potassium acesulfamate (ACE-K) via an acid-base reaction. The use of acesulfamate ILs as electrolytes was investigated by mixing with sodium or lithium acesulfamate salts and characterisation of their physicochemical and electrochemical properties. Polyethylene oxide based free standing membranes composed of [N2222][ace] with Na or Li [ace] were fabricated and tested in symmetrical Li or Na metal cells, demonstrating good electrochemical performance in both variable current density tests and longer-term cycling at elevated temperatures. Thus, the new Li and acesulfamate salts, the ILs and their mixtures, represent valuable new materials for the development of fluorine free electrolytes for energy storage devices.

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

1. Introduction

Cost and performance optimisation has been the driving force behind the development and manufacturing of lithium and sodium ion batteries. Advancements in battery technologies will enable the more effective storing of energy from sustainable sources, to enable mobility and further integration of unpredictable renewable sources. However, the development of battery materials often neglects safety and sustainability considerations [1], depending on hazardous, toxic and environmentally harmful chemicals used in the electrodes and/or the electrolyte formulation [2].

The electrolyte is a vital component of the battery as it facilitates the transport of metal ions between the electrodes and therefore must meet multiple requirements [3]. The need for high ionic conductivity [4, 5], good film-forming ability [6], and sufficient electrochemical stability [7], has driven the use in commercial electrolytes of highly fluorinated salts such as lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6) dissolved in cyclic and linear organic carbonates [8], resulting in numerous compromises in terms of safety [9] and sustainability [2]. Currently, fluorinated and perfluorinated chemicals are subject to increasingly strict regulation under various laws and regulations, including the Toxic Substances Control Act [10] in the United States and the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) regulation in the European Union [11], and some countries have established their own specific laws and regulations to govern their production, use and disposal. These new legislation are often aimed at restricting the use of these chemicals due to their persistence in the environment and potential negative impacts on human health and the environment [12].

The use of hexafluorophosphate salts in carbonate solvents is a prevalent approach in commercial lithium and sodium-ion batteries due to their high ionic conductivities, electrochemical stability and effective protection of the metal current collector against corrosion [13, 14]. However, despite their advantages, hexafluorophosphate (PF6−), and bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide (FSI−)), ions are susceptible to hydrolysis and may result in the release of fluoride ions, causing potential toxicity [15]. The bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (TFSI−) anion is a more recyclable and stable alternative to the FSI− and PF6− anions, however is known to be environmentally persistent [16].

Given the drawbacks of the use of fluorinated chemicals, the development of non-fluorinated anions is important [16]. Anions investigated to-date include bis(oxalate)borate (LiBOB, NaBOB) [17, 18], dicyanamide (LiDCA, NaDCA) and tricyanomethanide (TCM) [19], and Hückel anions [20]. However, achieving sufficient conductivity and electrochemical stability can be a challenge [21].

The quest to shift away from conventional flammable electrolytes [20], has led to the emergence of ionic liquids (ILs) as promising alternatives [22–26]. These materials are considered safer and more durable electrolytes, owing to their good thermal stability and minimal vapour pressure, and many possess additional advantageous characteristics such as broad electrochemical stability windows, high conductivity and chemical stability [27].

For the development of solid electrolytes, to eliminate leakage, solid polymer electrolytes (SPEs) based on polyethylene oxide (PEO) have been widely researched and are utilised in personal electronic devices using lithium metal batteries [28]. However, one of the major drawbacks of SPEs is their lower ionic conductivity compared to their liquid counterparts [29]. Of all the attempts to increase their conductivity, the plasticizing of the SPEs with ILs is worth highlighting as ILs are non-flammable and often more thermally and electrochemically stable than the polymer and thus contribute to the safety of the cell. These ternary SPEs (TSPEs) have been widely investigated and it is known that the IL increases the segmental motion of the polymer segments and thereby accelerates the metal ion transport. Unfortunately, from an environmental point of view, lithium salts and ILs for SPEs and TSPEs are almost exclusively based on highly fluorinated anions, such as TFSI. There are just a few example of non-fluorinated lithium salt and ILs (e.g. LiDCTA and N-butyl-N-methyl pyrrolidinium DCTA respectively) where ILs have been used to improve the sustainability and safety of TSPEs [24–26, 30–32]. Thus, more effort is required to develop more sustainable alternatives, and in this work a PEO solid state electrolyte is developed utilising the new acesulfamate-based salts and IL.

In the literature, biocompatible and biodegradable ILs have been introduced, mostly in the biomedical field as additives for active pharmaceutical ingredients [33, 34]. Choline-based ILs show better properties than other ILs such as low-toxicity, biocompatibility and biodegradability due to the use of the choline cation as a basic component of vitamin B4 [35]. This compound is classified as provitamin in Europe, and is considered safe by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Food Safety Agency and other regulatory agencies [36]. Acesulfame was introduced as an anion in choline based ILs, showing promising hydrogen bonding properties and high biocompatibility, however no electrochemical data of this anion was available [35]. The authors reported a 48 h EC50 value (the concentration estimated to immobilise 50% of Daphnia magna, a freshwater crustacean) of 1378 mg l−1, which is indicative of low toxicity. Pernak et al [37] introduced tetralkylphosphonium acesulfamate ILs for solvent extraction and as anti-electrostatic agents and solar cells electrolytes, and a cyclic voltammetry (CV) was reported, but no further electrochemical or thermochemical studies were performed. Guanidinium acesulfamate ILs have been synthesised as room temperature ILs [38], and tetra-alkyl ammonium acesulfamate ILs were suggested as an additive in consumer product formulation [39]. Stachowiak et al [40] and Kaczmarek et al [41] independently introduced tetraalkoxy acesulfamate ILs and dicationic tetraalkyl ammonium acesulfamate ILs and as antifeedant agents, and recently, Jones et al [42] reported the synthesis of triphenyl-2-pyridylphosphonium acesulfamate.

The purpose of this work is to introduce acesulfamate sodium and lithium salts, ILs and new electrolytes developed using acesulfamate salt/IL combinations. The acesulfamate anion, [ace]−, is a safe, cost effective, commercially available, stable anion derived from the well-known sweetener (ACE-K) with interesting thermochemical and electrochemical properties (i.e. Eox 2.5 V vs Fc+/Fc) [37]. It is proposed that Li and Na Ace salts are unlikely to release harmful products up to their degradation temperature (i.e. above 200 °C) [39], be water stable [39], which will assist with recycling, and less environmentally persistent than perfluorinated anions. In the future, these new non-fluorinated Na and Li salts could be used for electrolyte development by combination with other ILs/polymers/solvent systems. Thus, this work addresses the UN SDGs by contributing to the development of energy storage technologies, to support renewable energy use, and promoting the use of less harmful, more environmentally friendly chemicals.

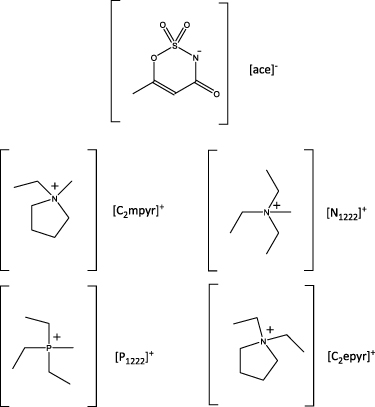

Here, the cations used to synthesise the acesulfamate ILs, [N1222]+, [P1222]+, [C2mpyr]+, [C2epyr]+ (figure 1) were chosen based on previous work that showed the good electrochemical and transport properties achieved when these cations were combining with anions such as FSI [20, 43]. Subsequently, the new IL [N1222][ace] was selected for investigation in Na and Li[ace] mixtures because of the widest electrochemical window stability and good ionic conductivity. Finally, this work demonstrates good Li electrochemistry in these mixtures with an initial investigation of the metal plating and stripping on nickel, and the fabrication and testing in symmetrical coin cells of PEO solid state electrolytes comprising of the [N1222][ace] IL with Na or Li [ace]. Thus, this work contributes a promising new anion in the drive towards the development of high performance, fluorine-free ionic electrolytes.

Figure 1. Structures and abbreviations of cations and anion used in this work: 6-methyl-3,4-dihydro-1,2,3-oxathiazin-4-one 2,2-dioxide), [ace]−; N-ethyl-N-methylpyrrolidinium, [C2mpyr]+; N-triethyl-N-methylammonium), [N1222]+; methyltriethylphosphonium, [P1222]+; N,N-diethylpyrrolidinium, [C2epyr]+ .

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image2. Experimental

2.1. Materials and methods

ILs and Li, Na salt precursors. The four new ILs, namely triethylmethylammonium 6-methyl-3,4-dihydro-1,2,3-oxathiazin-4-one 2,2-dioxide, [N1222][ace]; N-ethyl-N-methylpyrrolidinium 6-methyl-3,4-dihydro-1,2,3-oxathiazin-4-one 2,2-dioxide, [C2mpyr][ace]; N,N-diethyl-N-methylpyrrolidinium 6-methyl-3,4-dihydro-1,2,3-oxathiazin-4-one 2,2-dioxide, [C2epyr][ace]; methyltriethylphosphonium 6-methyl-3,4-dihydro-1,2,3-oxathiazin-4-one 2,2-dioxide, [P1222][ace]; sodium (6-methyl3,4-dihydro-1,2,3-oxathiazin-4-one 2,2-dioxide), Na[ace]; and lithium (6-methyl-3,4-dihydro-1,2,3-oxathiazin-4-one 2,2-dioxide), Li[ace], were synthesised (vide infra) using the following reagents (ex. Aldrich, 99%) without further purification: N,N-diethylethanamine, methyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate, N-methylpyrrolidine, N-ethylpyrrolidine, methyltriethylphosphonium methyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate, ethyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate, potassium 6-methyl-1,2,3-oxathiazin-4(3H)-one 2,2-dioxide, hydrochloric acid, sodium hydroxide, lithium hydroxide, poly ethylene oxide (106 Da). When required, dichloromethane, acetone, chloroform were dried using standard methods prior to use.

3. Methods

The ILs [N1222][ace], [P1222][ace], [C2mpyr][ace], [C2epyr][ace], and salts Li[ace], Na[ace] were synthesised according to the schemes reported in Scheme 1, and characterised using 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, 22Na-NMR, 7Li-NMR spectroscopy, and electrospray mass spectrometry (ESMS). All salts and ILs were dried at 50 °C for at least 24 h before use and subsequently handled in an Ar glove box. The ILs [N1222][ace], [P1222][ace], [C2mpyr][ace], [C2epyr][ace] were studied by examining conductivity, thermochemical properties differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), electrochemical oxidative stability and electrochemical stability window. The IL [N1222][ace] and its Na[ace] and Li[ace] mixtures were further investigated in terms of solid–liquid equilibria (SLE) and metal plating/stripping process utilising CV techniques.

NMR. Liquid state 1H, 13C, 7Li, 22Na-NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance III 400 MHz spectrometer and an Oxford X-pulse NMR 40 MHz.

ESMS. ESMS measurements were carried out on an Agilent 1200 series HPLC system. Both positive and negative ions were detected. Samples were injected as dilute solutions in ethanenitrile.

DSC. DSC-scans were recorded using a Netzsch DSC 214 Polyma model with a scan rate of 10 °C min−1 (sample size 5–10 × 10−3 g prepared in an aluminium pan under inert atmosphere). For each sample, three scans were run, and the heat flow and temperature were calibrated with cyclohexane.

Inductive coupled plasma-MS. The content of lithium, sodium, potassium and chloride in the samples was quantified by inductively coupled plasma MS on PerkinElmer NexION 2000.

Determination of SLE. The cloud point of a material was used to measure the onset of solid–liquid immiscibility. Cloud points were determined at atmospheric pressure using visual detection of the phase demixing (naked eye observation of turbidity followed by phase separation). Samples of the solutions were prepared in a closed Pyrex-glass vial with a stirrer inside [44].

Electrochemical characterisation. All CV was carried out using a Biologic SP200 potentiostat in an argon-filled glove box. The electrochemical stability window of the ILs was tested using CV. The acesulfamate salts were tested in an ethanonitrile mixture (1 g l−1) at room temperature. The electrode used were glassy carbon (working electrode), Pt wire (counter electrode) and Ag/Ag trifluoromethanesulfonate (OTf) (reference electrode). The electrochemical window of the ethanenitrile was recorded in a mixture with TBABF4 (1 g l−1).

Symmetrical Li and Na metal coin-cells were fabricated in an Ar-filled glovebox with the ≈150 µm PEO membrane as the SPE. The Na0 electrodes were prepared by rolling-out a Na0 chunk into a foil. 8 mm diameter disks were punched from the respective Li0 (100 µm thick) and Na0 (≈150 µm thick) foils. The coin-cells were tested using a VMP3 potentiostat (BioLogic) placed in heating chamber at 70 °C. After resting for 24 h at that temperature, the cells underwent a C-rate test of 10 cycles at each current density (0.02; 0.04; 0.06; 0.08; 0.1; 0.25 and 0.5 mA cm−2), with 1 h charge and 1 h discharge per cycle. Long term cycling was also performed at 0.1 mA cm−2.

4. Synthesis

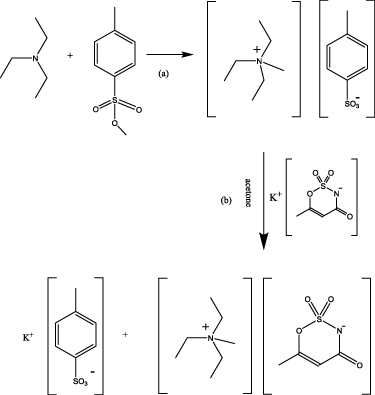

Here a novel synthetic approach is described to produce ammonium and pyrrolidinium tosylate precursors for the preparation of halide free ILs.

4.1. Synthesis of [N1222][ace]

(a) Synthesis of [N1222][oTs], (N,N-diethylethanaminium) methyl4-methylbenzenesulfonate: A mixture of the distilled N,N-diethylethanamine (10.00 g, 0.0988 mol) and methyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate (18.40 g, 0.0988 mol) was stirred (500 rpm) at room temperature in air for 2 d. The white residue was then washed with ethoxyethane (20 cm3, two times), cyclohexane (20 cm3, two times) and finally was concentrated using a rotary evaporator in vacuo at 40 °C to leave a hygroscopic white solid, which was subsequently dried in vacuo on a Schlenk line (0.05 mbar) at 35 °C for 2 d (22.36 g, 78% yield). 1H NMR (δH/ppm, 400 MHz, (CD3)2CO): 1.32 (t, 9H); 2.31 (s, 3H); 3.10 (s, 3H); 3.66 (m, 4H); 6.20 (q, 6H); 7.11 (d, 2H); 7.66 (d, 2 H).

(b) Synthesis of [N1222][ace]: potassium acesulfamate (3.50 g, 0.0174 mol) was added to a solution of the methyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate salt (5.00 g, 0.0174 mol) in acetone (20 cm3), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 d, after which it was filtered to remove the solid. The solvent was removed from the filtrate in vacuo using a rotary evaporator at 30 °C to leave a white solid, which was subsequently dried in vacuo (0.05 mbar) on a Schlenk line at 35 °C for 2 d (3.88 g, 80% of yield). ES-MS (CH3CN): calculated. M+: 116.14, M-: 161.99; found M+: 116.0, M-: 162.0. 1H NMR (dH/ppm, 400 MHz, (CD3)2CO): 0.74 (t, 9H); 1.45 (s, 3H); 2.42 (s, 3H); 2.80 (m, 4H); 4.80 (s, 1H). 13C NMR: 167.72, 159.51, 101.90, 54.82, 45.84, 29.74, 19.36, 7.27.

4.2. Synthesis of [C2mpyr][ace]

(a) Synthesis of [C2mpyr][oTs], N-ethyl-N-methylpyrrolidinium methyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate. A mixture of the distilled N-methylpyrrolidine (5 g, 0.587 mol), and ethyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate (11.76 g, 0.587 mol) was added in air to a round bottom flask. The mixture was then stirred (500 rpm) at room temperature 25 °C for 2 d. The off-white residue was then washed with ethoxyethane (20 cm3 two times), cyclohexane (20 cm3, two times) and finally was concentrated using a rotary evaporator in vacuo at 35 °C to leave a hygroscopic white solid, which was subsequently dried in vacuo on a Schlenk line at 35 °C for 2 d (10.33 g, 62% of yield). 1H NMR (dH/ppm, 400 MHz, (CD3)2CO): 0.80 (t, 3H); 1.61 (m, 4H); 1.84 (s, 3H); 2.49 (s, 3H); 2.97 (m, 4H); 6.66 (d, 2H); 7.02 (d, 2H).

(b) Synthesis of [C2mpyr][ace]. Potassium acesulfamate (2.96 g, 0.0175 mol) was added to a solution of the ethyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate salt (5.00 g, 0.0175 mol) in acetone (20 cm3), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 d, after which it was filtered to remove the solid. The solvent was removed from the filtrate in vacuo using a rotary evaporator in vacuo at 35 °C to leave a white solid, which was subsequently dried in vacuo on a Schlenk line at 35 °C for 1 d (3.75 g, 78% of yield). ES-MS (CH3CN): calcd. M+: 114.13, M-: 161.99; found M+: 113.9, M-: 162.0. 1H NMR (dH/ppm, 400 MHz, (CD3)2CO): 0.72 (t, 3H); 1.41 (m, 4H); 1.73 (s, 3H); 2.33 (s, 3H); 2.65 (m, 4H), 5.34 (s, 1H). 13C NMR: 170.82, 165.31, 99.34, 62.78, 55.25, 22.78, 21.44, 22.43, 9.18.

4.3. Synthesis of [C2epyr][ace]

(a) Synthesis of [C2epyr][oTs], N,N-diethylpyrrolidinium methyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate. A mixture of the distilled N-ethylpyrrolidine (5.00 g, 0.0504 mol), and ethyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate (10.10 g, 0.0504 mol) was added in air to a round bottom flask. The mixture was then stirred (500 rpm) at room temperature 25 °C for 2 d. The white residue was then washed with ethyl ethanoate (20 cm3 two times), cyclohexane (20 cm3, two times) and finally was concentrated using a rotary evaporator in vacuo at 35 °C to leave a hygroscopic white solid, which was subsequently dried in vacuo on a Schlenk line at 40 °C for 3 d (12.02 g, 80% of yield). 1H NMR (dH/ppm, 400 MHz, (CD3)2CO) 1.20 (t, 6H), 1.92 (m 4H), 2.18 (s, 3H, 3.37 (q, 4H, 4.19 (m, 4H), 6.97 (d, 2H), 7.54 (d, 2H).

(b) Synthesis of [C2epyr][ace]. Potassium acesulfamate (2.82 g, 0.0167 mol) was added to a solution of the ethyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate salt (5.00 g, 0.0167 mol) in dichloromethane (20 cm3), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 d, after which it was filtered to remove the solid. The solvent was removed from the filtrate in vacuo using a rotary evaporator in vacuo at 35 °C to leave a white solid, which was subsequently dried in vacuo on a Schlenk line at 40 °C for 1 d (3.25 g, 67% of yield). ES-MS (CH3CN): calcd M+ 128.14, M 161.99: found M+: 128.0, M-: 162.0. 1H NMR (dH/ppm, 400 MHz, (CD3)2CO) 1.37 (t, 6H), 2.19 (s, 3H, 2.23 (m, 4H, 3.55 (q, 4H, 5.04 (m, 4 H), 6.40 (s, 1H). 13C NMR: 171.85, 168.35, 97.52, 62.78, 55.25, 22.78, 21.44, 20.62.

Synthesis of [P1222][ace]. Potassium acesulfamate (3.31 g, 0.0164 mol) was added to a solution of the methyltriethylphosphonium methyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate salt (5.00 g, 0.0164 mol) in acetone (20 cm3), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 d, after which it was filtered to remove the solid. The solvent was removed from the filtrate in vacuo using a rotary evaporator in vacuo at 35 °C to leave a white solid, which was subsequently dried in vacuo on a Schlenk line at 40 °C for 1 d (2.67 g, 55% of yield). ES-MS (CH3CN): calcd. M+: 131.11, M−: 161.99: found M+: 131.0, M−: 162.0. 1H NMR (dH/ppm, 400 MHz, (CD3)2CO): 1.30 (m, 9H); 1.88 (s, 3H); 1.98 (s, 3H); 2.44 (m, 6H); 5.27 (s, 1H). 13C NMR: 169.70, 160.95, 103.66, 20.48, 14.25, 13.71, 6.23, 3.43, 2.71.

4.4. Synthesis of Li[ace] and Na[ace]

(a) Synthesis of H[ace]. Potassium acesulfamate (10.00 g, 0.0497 mol) in MQ water (20 cm3) was added to a solution of HCl 37% (5.43 g, 0.0497 mol), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h, after which it was transferred into a separating funnel and dichloromethane added for a subsequent solvent extraction. The dichloromethane fraction was transferred into a round bottom flask and dried using a rotary evaporator in vacuo at 40 °C to leave a white solid, which was subsequently dried in vacuo on a Schlenk line at 35 °C for 1 d. The protocol was repeated until the semi-quantitative yield was reached (7.33 g, 90% of yield). 1H NMR (δH/ppm, 400 MHz, CDCl3): 2.81 (s, 3H); 6.48 (s, 1H); 7.91 (s, 1H).

(b) Synthesis of Li[ace]. Lithium hydroxide (9.50 g, 0.0472 mol) solution in water (20 cm3) was added to a solution of the hydro (6-methyl-3,4-dihydro-1,2,3-oxathiazin-4-one 2,2-dioxide) (10.00 g, 0.0472 mol) in MQ water (20 cm3), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature and titrated to a neutral pH value (7.0), after which it was transferred into a round bottom flask and the water removed using a rotary evaporator in vacuo at 50 °C to leave a white solid, which was subsequently dried in vacuo on a Schlenk line at 40 °C for 1 d (9.63 g, 93% of yield). ES-MS (CH3CN): calcd M+–M− adduct: 233.0; found M+–M− adduct: 233.0. 1H NMR (δH/ppm, 400 MHz, D2O): 2.27 (s, 3H); 5.83 (s, 1H). 7Li NMR (δH/ppm, 400 MHz, D2O) 10.5 13C NMR: 168.45, 160.02, 102.56, 19.20. Combined melting and decomposition temperature >200 °C.

(c) Synthesis of Na[ace]. Sodium hydroxide (9.50 g, 0.0472 mol) solution in water (20 cm3) was added to a solution of the hydro 6-methyl-1,2,3-oxathiazin-4(3H)-one 2,2-dioxide (10.00 g, 0.0472 mol) in MQ water (20 cm3), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature and titrated to a neutral pH value (7.0), after which it was transferred into a round bottom flask and the water removed using a rotary evaporator in vacuo at 50 °C to leave a white solid, which was subsequently dried in vacuo on a Schlenk line at 40 °C for 1 d (10.36 g, 91% of yield). ES-MS (CH3CN): calcd. M+-M- adduct: 249.0; found M+-M- adduct: 249.0. 1H NMR (δH/ppm, 400 MHz, D2O): 2.25 (s, 3H); 5.81 (s, 1H). 22Na NMR (δH/ppm, 40 MHz, D2O) 8.65; 13C NMR: 169.72, 160.45, 103.22, 19.11. Combined melting and decomposition temperature >200 °C.

4.5. Fabrication of the PEO/Li[ace] solid state electrolyte

Free-standing PEO-Li[ace] polymer membranes were prepared by mixing PEO and Li[ace] and N1222[ace] in water (100 ml). The mixture was left stirring at room temperature for 24 h to improve the homogeneous dissolution of Li[ace] in PEO. The mixture was then left drying at room temperature to obtain a polymeric membrane, and subsequently in vacuo on a Schlenk line at 40 °C for 1 d. The resulting material was sandwiched between Mylar foil sheets and hot-pressed for 1 min at 60 °C with an applied pressure of 0.2 bar, obtaining a self-standing membrane. The thickness of the resulting membrane, in the range of 200 ± 5 µm, was controlled by use of a spacer (Mylar foil), and then the membrane was dried in vacuo on a Schlenk line at 40 °C for 3 d. The specific EO:Li+ or EO:Na+ molar ratios, together with the Li[ACE]:N1,2,2,2[ACE] and Na[ACE]:N1,2,2,2[ACE] ratios, are detailed in the corresponding sections and SI. For results in the main text, SPEs were prepared with EO:x[ACE]:[N1,2,2,2][ACE] in a 12:0.25:0.75 molar ratio, where x = Li+ or Na+ as specified.

5. Result and discussion

IL synthesis and characterisation. The synthesis of [N1222][ace], [C2mpyr][ace], [C2epyr][ace] and [P1222][ace] (figure 1) further advances the state of the art on the synthesis of acesulfamate based ILs by using the methyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate synthetic route (scheme 1) [45]. This synthetic route avoids halogen impurities (e.g. Cl−) which can have an effect on the material physical properties (e.g. ILs with [Cl−] ∼0.5 mol kg−1 Cl− can lead to a 36% increase in viscosity) and electrochemical stability/performance [34] 1H-NMR and ES-MS data confirmed the identity and purity of these novel liquids. In particular, the integration of the 1H-NMR spectra confirmed the 1:1 molar ratio between the anion and the cation and the absence of organic impurities.

Scheme 1. Synthetic scheme for the preparation of [N1222][ace]: (a) quaternisation of the tertiary amine, (b) anion metathesis.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image5.1. Thermal and transport properties of the neat ILs

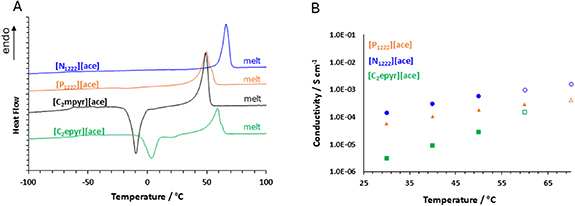

DSC was used to study the thermochemical properties of the acesulfamate ILs. All the synthesised salts exhibited melting points below 100 °C (see figure 2(A)), allowing their classification as ILs [27]. These materials have melting points between 40 and 70 °C, which is in the same range as other previously reported acesulfamate based ILs [40, 46, 47]. For all four new ILs the reported entropy of fusion (ΔSf) is between 40 and 90 J mol−1 K−1 and, with the exception of a very small peak in the first heating trace of the [N1222]+ salt in only the first heating trace, no solid–solid phase transitions were observed. Thus, unlike the FSI and TFSI salts of these cations [27, 48], they show no plastic crystal behaviour according to Timmermans classification [49].

Figure 2. (A) DSC thermograms (heating rate 10 °C min−1, 2nd cycle) of the acesulfamate-based ionic liquids. (B) Ionic conductivity of acesulfamate ionic liquids recorded during second heating cycle, measured by EIS as a function of temperature (30 °C–70 °C). The filled symbols represent the data of the materials in the solid state and the hollow symbols represent the data of the liquid state.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe glass transition temperature range for the [C2mpyr][ace] and the [C2epyr][ace] (−63 °C and −60 °C, respectively) is similar to the Tg of the acesulfame ILs described in the literature, which also reports that elongation of the alkyl chain in the cation results in an increase in Tg. For example, Stachowiak et al reported a Tg of −57.3 °C for [N112(1O1OH)][ace], although this material is reported to be liquid at room temperature as a result of the hydroxylated alkyl chain on the ammonium cation [40]. Furthermore, here both pyrrolidinium ace ILs show a crystallisation before their melting point (a cold crystallisation). This indicates a structural rearrangement upon heating and more hindered kinetics of crystallisation than in the phosphonium or ammonium salts, although the [P1222][ace] also shows significant supercooling (figure S4).

The conductivity as a function of temperature is given in figure 2(B). For comparison to other solid salts, the [C2epyr][ace] displayed a conductivity of 3.1 × 10−6 S cm−1 at 30 °C, which is lower than the FSI analogue (1.9 × 10−5 S cm−1)[50]. In contrast, the conductivity of the [P1222][ace] (5.8 × 10–5 S cm−1) is higher than the corresponded [P1222][FSI] (2 × 10−7 S cm−1 at 30 °C)[51]. Imaging studies have shown that the conductivity of the FSI salt depends on the thermal history of the sample (i.e. slow cooling vs rapid cooling), and the significant supercooling observed for the [P1222][ace] (figure S4) suggests that thermal history may also be important in this new material. The [N1222][ace] has a conductivity of 1.4 × 10−4 S cm−1 at 30 °C, which is higher than [N1222][FSI] (9.9 × 10−6 S cm−1) that has been demonstrated as a potential electrolyte for Li batteries [48]. As the [N1222][ace] showed the highest conductivity of the new ILs reported here, this material was chosen for further investigation for electrolyte development.

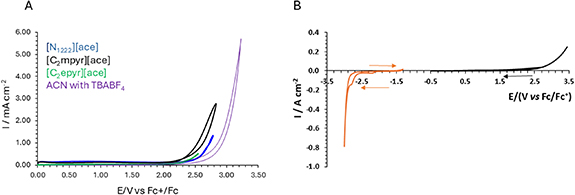

5.2. Electrochemical properties

The stability towards oxidation and reduction is a key property for ionic electrolytes utilised in energy storage technologies, strongly influenced by the functional groups and the molecular structure of the ion pair[52]. Here, the oxidative stability of acesulfamate ILs was tested using a procedure similar to Pernak et al [37] for phosphonium acesulfamate ILs, where they reported an oxidation potential of ∼2.2 V vs Fc/Fc+. Measurement of the oxidation potential of the ammonium and pyrrolidinium acesulfamate ILs was carried out in ethanenitrile mixtures (1 g l−1) using glassy carbon as working electrode (figure 3(A)). All the acesulfamate ILs showed oxidative stability between 2.1–2.5 V vs Fc/Fc+, which is in good agreement with the oxidative potential previously reported for other ace-salts [37]. These oxidation potentials are also very similar to piperidinium FSI− and TFSI− salts, Eox = 2.4 V and 2.5 V vs Fc/Fc+[53].

Figure 3. (A) CV of the [N1222][ace], [C2epyr][ace] and [C2mpyr][ace] dissolved in ethanenitrile 0.1 g l−1, ACN with TBAPF6 0.1 g l−1 recorded with scan rate 10 mV s−1 on GC working electrode, with Pt counter electrode and Pt as pseudo reference electrode. (B) CV of molten [N1222][ace] at 10 m V s−1, on GC working electrode, Pt counter electrode and Ag/AgOTf as reference electrode at 60 °C in an Ar filled glove box.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe [N1222][ace] showed the highest oxidation stability therefore further tests were carried out on the neat material above its melting point. The electrochemical stability of the IL [N1222][ace] was evaluated using CV at 60 °C, shown in figure 3(B). The IL shows the main reductive peak below −3 V (V vs Fc/Fc+), and oxidation peak above 2 V (V vs Fc/Fc+). This stability for the neat materials is sufficient to encourage their further investigation as electrolytes for Li and Na batteries, also noting that the addition of Li/Na salts may further increase the electrochemical stability[54]. Furthermore, thermogravimetric analysis of this salt shows a decomposition temperature (5% weight loss) of 242 °C (figure S10)

5.3. Thermal properties of the IL-acesulfamate salt mixtures

The [N1222][ace] showed the highest ionic conductivity of the new acesulfamate ILs (1.4 × 10−4 S cm−1 at 30 °C), the best oxidative stability and lowest melting point (Tm = 55 °C), therefore this IL was used for investigation of the applicability as an electrolyte by mixing with the new Li and Na acesulfamate salts.

In electrolyte development, Na and Li salts can be mixed with salts that are solid at RT to obtain eutectic mixtures, aimed at achieving high alkali metal mobility and superior ionic conductivity [55, 56]. The depth of the eutectic point for these mixtures depends on the strength and nature of the physicochemical interaction of the sodium or lithium salts with the IL [57]. For example, a pyrrolidinium TFSI salt mixed with NaTFSI or LiTFSI has shown different phase behaviour, where the eutectic composition and temperature differ substantially: 63 °C at 15 mol% for the Na mixture and 30 °C at 33 mol% for the Li mixture [55]. There is also increasing recognition of the benefits of high salt concentration (e.g. 50% salt) electrolytes [58, 59]. Here the partial phase diagram and the ionic conductivity of the Li and Na mixtures have been used to guide the development of the electrolytes with optimum transport properties.

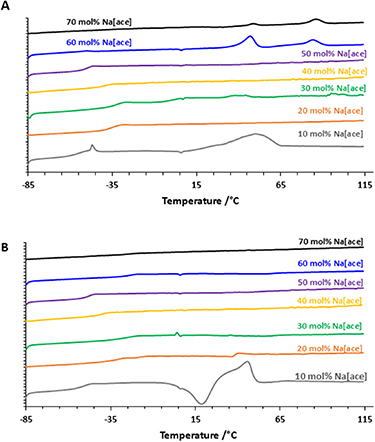

Addition of Sodium acesulfamate to [N1222][ace]. DSC heating traces for the mixtures of [N1222][ace] with Na[ace] salt are presented in figures 4(A) and (B). The addition of sodium salt to [N1222][ace] significantly changes the thermal behaviour: the mixtures with an increasing amount of sodium salt are characterised by lower melting point (e.g. 30 °C at 10 mol% of Na[ace]) and different glass transitions. The melting point is not detectable by DSC between 20 and 50 mol% of sodium salt, and it is then detected again at 80 °C for the 60 and 70% mol mixtures.

Figure 4. DSC thermograms, heating rate 10 °C min−1, cycle 1 (A) and cycle 2 (B) of the acesulfamate based ionic liquids and their Na[ace] mixtures at different molar concentrations.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageAnalysis of the second cycle of heating-cooling (figure 4(B)) shows the consistent loss of order of the structure after melting for the mixtures between 20 and 50 mol % of Na[ace] salt. The 10 mol % Na[ace] shows a broadened and asymmetric melting peak (Tm = 53 °C) on the first heating cycle (figures 4(A))and(a) cold crystallisation peak (Tc = 19 °C) on the second heating cycle. The small solid–solid transition that was observed in the first cycle of the neat material is also visible in the 10% mixture, but again does not appear in the second scan, and is not visible at higher salt concentrations. The broadening of the melting peak and its shift toward lower temperatures relative to the neat IL and Na[ace] is a common observation of this type of salt mixture, attributed to each substance acting as an impurity within the other which promotes disorder and reduces the energy required to melt the sample.

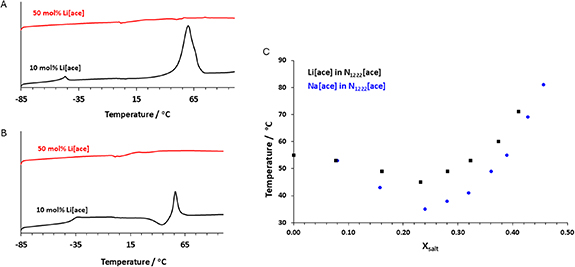

Addition of Lithium acesulfamate to [N1222][ace]. DSC heating traces of mixtures with Li[ace] (red and black) at 10 and 50 wt% are presented in figures 5(A) and (B). As it was hard to identify melting points using DSC (due to the very broad transitions) this analysis was only performed on the 10% and 50% lithium systems, before the full range was examined using visual melting as detailed below.

Figure 5. DSC thermograms (heating rate 10 °C min−1) of the acesulfamate ILs and their Li[ace] mixtures at two different molar fractions, (A) 1st scan, (B) 2nd scan. (C) Visual melting point of the Li[ace]/ [N1222][ace] and Na[ace]/ [N1222][ace] mixtures, measured in an Ar glove box. The melting point was measured on repeated heating and cooling cycles in a Pyrex conical vial and continuously stirred sample.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe neat IL is characterised by one solid–solid phase transitions (at −43 °C) on the first heating cycle followed by melting at 55 °C. Mixtures with Li[ace] are characterised by lower melting point (e.g. 50 °C at 10 mol % of Li[ace], figure 5). The first heating cycle for the 10 mol % Li[ace] in [N1222][ace] showed the melting point peak, but there is supercooling that results in the appearance of Tg then a cold crystallisation peak followed by the melting on the second heating cycle. Similar behaviour was observed for the Na[ace] salt mixtures and has been reported for Na and Li salt mixtures with organic ionic plastic crystals [60, 61].

As the broad peaks in the DSC of the salt-containing electrolytes make detection of the melting points difficult, the visual melting points of the electrolytes were analysed to further understand the phase behaviour. The data points in figure 5 indicate the temperature below which there is a solid phase present.

The mixtures of the [N1222][ace] and the Na [ace] (in blue) and Li [ace] (in black), figure 5(C), displayed a lower melting point compared with the neat [N1222][ace], in agreement with the DSC data. Interestingly, both salt mixtures exhibit a melting point minimum at around 25 mol% of salt, and the eutectic temperature is lower for Na than Li: approximately 35 °C for the Na[ace] mixture and 45 °C for the Li[ace] mixture. Following these results, the transport properties of the 25% mixtures were then evaluated and compared to those of the neat and 50% mixtures, discussed below.

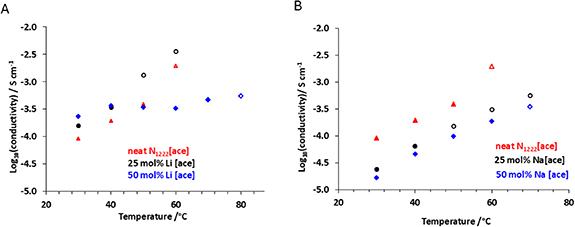

5.4. Ionic conductivity of IL and Li[ace], Na[ace] mixtures

The ionic conductivity of the [N1222][ace] mixtures with Li[ace] and Na[ace] was measured across a range of temperatures, shown in figure 6. The neat IL showed a relatively high conductivity across the studied temperature range, and the 25% Li[ace] mixture is slightly higher with the same temperature trend (see figure 6(A)). However, the 50% Li[ace] mixture is solid over a wider temperature range and thus has lower conductivity at the higher temperatures.

Figure 6. Ionic conductivity of acesulfamate based IL mixtures recorded during the second heating measured by EIS, (A) Li[ace]/[N1222][ace] mixtures, (B) Na[ace]/[N1222][ace] mixtures. The filled marks represent the data of the materials that are either fully or partially solid, and the empty marks represent the data in the liquid state.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe data shown in figure 6(A) demonstrate a consistent trend with the expected higher value of the ionic conductivity when the mixture is in a liquid state (empty circles compared to the solid mixtures, filled circles, in figure 6(A). The 25% Li [ace] sample also has consistently higher conductivity than the neat OIPC. The ionic conductivity of the [N1222][ace] with Na[ace] mixtures, figure 6(B), shows similar conductivity vs temperature trends to the neat material, within the temperature range studied, but with slightly lower conductivity.

5.5. Li and Na electrochemistry

The Li and Na [ace] salts showed promising properties when mixed with [N1222][ace], with ionic conductivity in the order of 10−4 S cm−1; values that have been shown to produce promising electrolyte formulations for both Li and Na ion batteries [62, 63]. To assess the suitability of the electrolyte to support lithium electrochemistry, the lithium metal plating and stripping of 40 mol % of Li[ace] in [N1222][ace] at 65 °C (above the melting point) was investigated in a three electrode cell using a Ni working electrode. The CVs, shown in figure S4(A), show two reductive features in the first cycle indicative of SEI formation followed by an onset potential for Li deposition of −3.5 (V vs Fc/Fc+), and an increase in the striping peak current by the 10th cycle. The voltammogram profile is in good agreement with well-studied Li salt-in-IL mixtures such as [C4mpyr][TFSI]-LiTFSI] [64], but with the advantage that the new [ace]− based electrolyte removes the fluorinated component from the system.

For further assessment of electrochemical performance, the lithium or sodium ace salt and the [N1222][ace] IL were combined with poly(ethyleneoxide), PEO, a well-known and well-characterised polymer matrix, to make free standing and flexible membranes. PEO has been demonstrated to exhibit high compatibility with lithium salts, flexible mechanical properties, stability against lithium-metal and easy processing, thus, it has been extensively investigated as a polymer-based solid-state electrolyte combined with different conductive salts [28, 54, 65, 66]. This polymer has been mostly studied for lithium-based electrolytes, nevertheless, with sodium emerging as a highly promising alternative as mentioned above, research has also commenced on this system, yielding favourable outcomes [67, 68]. Here, PEO shows good compatibility with the ace salts, making it an ideal candidate for testing this novel salt in a real solid-state battery system. PEO can provide ionic conductivity since its polyether segments coordinate with lithium ions via coulombic interactions. This mostly occurs in the amorphous region of the polymer, dominated by an enhanced chain movement. However, at room temperature and below its melting point at 65 °C, PEO exhibits high crystallinity, and thus, low ionic conductivity [69, 70]. To improve that, here the electrochemical measurements were performed at a higher temperature (70 °C–80 °C as specified).

Initial electrochemical testing to demonstrate the stability of the ace anion against metal anodes was performed using a polymer electrolyte of Li[ace] and PEO, at a ratio of ethylene oxide units:Li+ (EO:Li) = 8:1, combined with the [N1222][ace] (8 mol %) to form a solid-state electrolyte that was tested at 75 °C. The cells were able to cycle for up to 277 h (figure S5) with some soft short circuit appearing mostly in one of the two cells. The electrochemical stability and Li deposition and stripping was also demonstrated using this polymer composition (figure S5). For initial testing in sodium cells, the Na[ace] was incorporated into a freestanding PEO membrane (11 mol% Na[ace] in PEO) and tested in a symmetrical coin cell assembly at 80 °C (figure S5(E)). The cycling of both the Li and Na symmetric cells without any significant increase in polarisation demonstrates that the chemical composition of the metal/electrolyte interface is stable within this time, indicating the suitability of the fluorine-free acesulfamate anion.

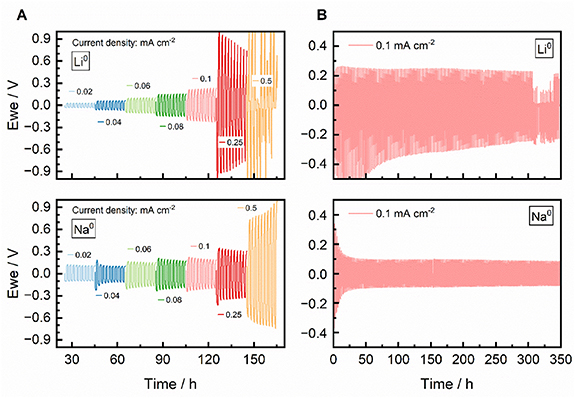

Following these promising results, the lithium and sodium electrochemistry was further improved using SPEs prepared with EO:x[ACE]:[N1,2,2,2][ACE] in a 12:0.25:0.75 molar ratio, where x = Li+ or Na+. Figure 7 shows the plating—stripping electrochemical performance of the Li0 and Na0 symmetrical cells, including both variable current density tests and longer-term cycling at 1 mA cm−2.

Figure 7. Electrochemical performance of SPEs with EO:x[ACE]:[N1,2,2,2][ACE] in a 12:0.25:0.75 molar ratio, where x = Li+ in the upper plots and x = Na+ in the lower plots. (A) 1 h plating—stripping at varying current densities and (B) 1 h plating—stripping at 0.1 mA cm−2, both measured in symmetrical Li0 and Na0 cells at 70 °C.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageIn figure 7(A), at lower current densities (<0.1 mA cm−2), the Li cell exhibits a lower initial overpotential compared to the Na cell. However, in the Li cell, a slight increase in polarisation is observed with each cycle. In contrast, the Na cell demonstrates an improved behaviour at higher current densities (> 0.1 mA cm−2), with a more stable and lower overpotential. Interestingly, at lower current densities, although the Na cell starts with a slightly higher overpotential than Li, it gradually decreases upon cycling, indicating the creation of a stable interface. In the longer-term cycling test (figure 7(B) and expanded version in figure S8), both Li and Na cells exhibit a stable performance up to 350 h. The overpotential in the Na cell decreases significantly from ca. 0.4 V to ca. 0.1 V, highlighting a more pronounced interfacial improvement compared to the Li cell, which decreases from ca. 0.4–0.3 V. This progressive reduction in overpotential, particularly in the Na system, demonstrates a formation of a robust and stable interface layer, obtaining promising cyclability. Therefore, the overall stable overpotential throughout the tests, without any significant increase in polarisation during the whole cycling, supports the suitability of the fluorine-free acesulfamate anion for use with both Li0 and Na0 anodes in Li- and Na-metal batteries.

6. Conclusions

Here, the synthesis of new non-fluorinated Li and Na salts and ILs is reported, utilising the cost effective, commercially available, biocompatible, and toxicologically safe potassium acesulfamate sweetener. The thermal and electrochemical properties and ionic conductivity demonstrate that the new [ace]− based ILs and their salts exhibit comparable advantageous properties to materials previously successfully utilised as electrolytes for energy storage, but with the additional advantage of no fluorination and a non-toxic anion. The ILs were also synthesised halide free in high yield using the tosylate route. The [ace]− ILs introduced in this work have melting points of 50 °C–60 °C and good ionic conductivity at 30 °C, e.g. 1.4 × 10−4 S cm−1 for the tetraalkylammonium [ace] IL, making them promising as electrolyte components.

The Na[ace] or Li[ace] salts were used to fabricate solid state electrolytes with promising thermal, transport and electrochemical properties by mixing the [N1222][ace] and PEO. Reversible lithium and sodium deposition and stripping in symmetric cells (70 °C–80 °C) is demonstrated, with good rate capability and stability, showing the feasibility of using these electrolytes in lithium or sodium batteries. For both the Li and Na electrolytes, optimisation of the salt, IL content and polymer type are predicted to yield further improvements in device performance. The Li[ace] and Na[ace] could also be used as a replacement for the commonly used FSI or TFSI salts in other polymer and IL systems to reduce the fluorine content. The initial electrochemical results reported here clearly demonstrate the suitability of the non-fluorinated ace anion to support both Li and Na electrochemistry and enable the development of safer, more environmentally friendly battery electrolytes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC) through the ARC Training Centre for Future Energy Storage Technologies IC180100049 (storEnergy).

Data availability statement

All data that support the findings of this study are included within the article (and any supplementary information files).

Supplementary data available at http://doi.org/10.1088/2977-3504/ae3d3d/data1.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work described in this study.