As Allen Ginsberg talks about his life and art, his most famous poem is illustrated in animation while the obscenity trial of the work is dramatized.As Allen Ginsberg talks about his life and art, his most famous poem is illustrated in animation while the obscenity trial of the work is dramatized.As Allen Ginsberg talks about his life and art, his most famous poem is illustrated in animation while the obscenity trial of the work is dramatized.

- Directors

- Writers

- Stars

- Awards

- 2 wins & 8 nominations total

Kaydence Frank

- Allen's Girlfriend

- (as Kadance Frank)

Allen Ginsberg

- Self

- (archive footage)

- Directors

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

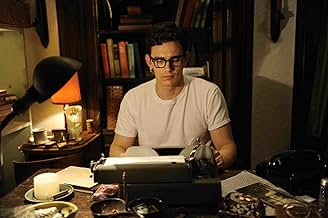

'Howl (2010)' is an offbeat experimental historical film about Allen Ginsberg's 1956 poem "Howl," the subject of a highly-publicised obscenity trial on its initial publication. James Franco plays Ginsberg, the reluctantly homosexual poet who poured his fears and frustrations into a four-part magnum opus, deemed a masterpiece and an obscenity in equal measure. I haven't read all that much poetry (though I have been known to recite Poe's "The Raven" in my most Vincent Price-ish voice), but I did like Ginsberg's poem, which is lyrical and evocative in a manner resembling the songwriting of Tom Waits. Several computer-animated sequences attempt to ascribe visuals to Ginsberg's words, but I wasn't sure about these: the CGI animation seemed too clean, too ordered, to represent such inner torment. Worth seeing, but perhaps not for everyone.

In admiration of James Franco and his portraying a literary person is why I wanted to see this film. Since I'd never read the poem "Howl" by Allen Ginsberg (& I knew of Ginsberg in his later years as he was fairly renown as almost an elder poet statesman), I actually dug up a copy of "Howl" and read it before I viewed the movie. It turns out that it wasn't necessary to have read "Howl" -- the film sufficiently presents the poem and its complete text so that the viewer gets a good understanding just from the movie itself (at least I thought so...). This occurs in not only Franco's public reading of "Howl," it is brought out in the animation aspect of the film -- for me the animation was unexpected yet not intrusive. What is the film's major strength is James Franco's portrayal of Ginsberg. Franco's actual physical resemblance to the younger Ginsberg adds to his portrayal and his public reading of "Howl" is also quite good.

What is additionally satisfying in my mind is the evoking of a time and place (mid 1950s America) when a group of writers and quasi-vagabonds lived their lives on their own terms (& not in accordance to what was then considered the status quo) and wrote about it. This is brought out in depictions of Ginsberg's relationships and also in the court room obscenity battle about "Howl."

What is additionally satisfying in my mind is the evoking of a time and place (mid 1950s America) when a group of writers and quasi-vagabonds lived their lives on their own terms (& not in accordance to what was then considered the status quo) and wrote about it. This is brought out in depictions of Ginsberg's relationships and also in the court room obscenity battle about "Howl."

I was lucky to watch this movie at the Athens Film Festival last Saturday and, despite its occasional flaws, I loved it. Ginsberg is fairly known to Greece , though most people (myself included) got to know him through his connection with Dylan. In that sense, I wasn't familiar with HOWL or the obscenity trial. For me , the movie's main attraction is the fact that it is not a biopic but a study on the creation of poetry, the power and magic of the words, the creator's struggle for genuineness through a dark path of madness and sexual frustration. The film is an unusual blend of poetry recitation, psychedelic animation, a graphic dramatization of Ginsberg's interview and a straight-forward dramatization of the trial.Some of them work fine and some not. Franco catches the right spirit of a young poet striving to find his way of expression and he is magnetic both in the recitation and in the interview scenes.The trial scenes , though well acted, seemed a little flat to me as compared to the vibrant tone that the poem itself imposes to the film . The animation was a bit uneven , in cases great (the Moloch section was terrific) , in cases indifferent and sometimes, for me, annoying. Apart from those parts that didn't work for me to the extend that I expected , the film is a unique docudrama, a magnificent and courageous ode to the power of words and the freedom of speech and a great depiction of the personal struggle of an artist to be truthful to himself.

Poetry can seriously damage your health. That's the main thing I've learned from recent biopics in which Johnny Depp's pox-ridden John Wilmot (The Libertine), Ben Whishaw's consumptive Keats (Bright Star) and Gwyneth Paltrow's depressive Sylvia Plath (Sylvia) have cornered the market in self-destructive behaviour.

I approached Howl, a movie about Beat Generation poet Allen Ginsberg, with a mixture of excitement and trepidation. On the one hand, it stars James Franco as Ginsberg and Mad Men's Jon Hamm as his lawyer, Jake Ehrlich. I'd watch these two ridiculously handsome actors in just about anything, but I really didn't want to sit through another Ode to Angst.

Directors Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman -- The Times of Harvey Milk, The Celluloid Closet – are renowned for their documentary work and this film was originally conceived along those lines. Ginsberg's epic poem "Howl" was first published in 1955, but its explicit references to drugs and homosexuality (amongst other things) led to the prosecution of his publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti in 1957. The intention was to commemorate the 50th anniversary of those events.

But instead of a straight documentary, the film-makers have opted to show us three sides of "Howl". There's the poem itself, with Franco trying to channel the spirit of Ginsberg as he addresses a rapt audience, in the b/w sequences from 1955. By contrast, the trial scenes are shot in colour and feature many voices with differing opinions about the merit of Ginsberg's work. Finally, the poet's own thoughts are recorded by an unseen interviewer. At the centre of all this, "Howl" is also given visual form, with a series of animations created by artist Eric Drooker.

For me, the courtroom scenes are the most enjoyable and thought-provoking element of the film. A succession of expert witnesses – some pompous, some just prejudiced – try to get to grips with issues of literary merit and the nature of obscenity. David Strathairn is admirably straight-faced in the role of prosecuting attorney Ralph McIntosh, as he tiptoes through a minefield of sexual imagery and baffling phrases like "angel-headed hipsters". Hamm's tight-lipped defence lawyer brings a sense of intellectual superiority to the proceedings – he's a crusading Don Draper with the added bonus of a moral compass.

Ginsberg himself wasn't on trial here and wasn't present at the proceedings, but the debate about whether the law is an effective tool for censoring and constraining artists remains highly topical. As one of the more thoughtful witnesses (played by Treat Williams) explains, "You can't translate poetry into prose. That's why it is poetry." The poet's own perspective on his life and work is captured in conversation with an off-camera reporter. A bearded, chain-smoking Ginsberg talks openly about his homosexuality, his mother's psychiatric problems, and fellow writer Carl Solomon, to whom "Howl" was dedicated. This strand of the film was inspired by a never-published interview that Ginsberg gave to Time magazine, but the film's dialogue is culled from a variety of sources.

Trying to explain the process of translating feelings into verse is a hard thing to pull off on film. Perhaps that's why most film-makers prefer to concentrate on the broken marriages and substance abuse that go hand in hand with tortured literary geniuses. Epstein and Friedman, who also wrote the screenplay, have done a good job trying to condense biographical detail and literary theory into what is basically a monologue – without being pretentious or boring. Brief flashbacks of Ginsberg pounding away at his typewriter, with his friend Neal Cassady, and in bed with long-term partner Peter Orlovsky, help to round out a portrait of the artist.

The final piece in the jigsaw – the poem – is the most problematic aspect of the film. How much of the work does the audience need to hear, and how do you hold their attention through some long and difficult passages? I quickly became bored of Franco's declamatory style, as he reads to a gathering of smug-looking hipsters at the Six Gallery in San Francisco.

When the recitation continues over Eric Drooker's animation, the effect is even worse. It's a matter of taste whether you thrill to the repeated imagery of fire, the minotaur-like Moloch and weirdly elongated bodies flying across the night sky. I prefer not to have someone else's interpretation of the verse foisted on me. Archive footage from the period would have been another option to fill the gap, but overall I think the poetry should have been used more sparingly.

Howl is bold, stylish attempt to capture a period in the mid-20th century when writing poetry could be an act of political rebellion – a shot across the bows of dull, conformist, heterosexual America. By casting the handsome and charismatic James Franco as Ginsberg, the directors could have turned this into yet another movie about the cult of personality. Instead they've largely succeeded in keeping the focus on the verse and on the act of writing. As the man said, "There's no Beat Generation. Just a bunch of guys trying to get published."

I approached Howl, a movie about Beat Generation poet Allen Ginsberg, with a mixture of excitement and trepidation. On the one hand, it stars James Franco as Ginsberg and Mad Men's Jon Hamm as his lawyer, Jake Ehrlich. I'd watch these two ridiculously handsome actors in just about anything, but I really didn't want to sit through another Ode to Angst.

Directors Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman -- The Times of Harvey Milk, The Celluloid Closet – are renowned for their documentary work and this film was originally conceived along those lines. Ginsberg's epic poem "Howl" was first published in 1955, but its explicit references to drugs and homosexuality (amongst other things) led to the prosecution of his publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti in 1957. The intention was to commemorate the 50th anniversary of those events.

But instead of a straight documentary, the film-makers have opted to show us three sides of "Howl". There's the poem itself, with Franco trying to channel the spirit of Ginsberg as he addresses a rapt audience, in the b/w sequences from 1955. By contrast, the trial scenes are shot in colour and feature many voices with differing opinions about the merit of Ginsberg's work. Finally, the poet's own thoughts are recorded by an unseen interviewer. At the centre of all this, "Howl" is also given visual form, with a series of animations created by artist Eric Drooker.

For me, the courtroom scenes are the most enjoyable and thought-provoking element of the film. A succession of expert witnesses – some pompous, some just prejudiced – try to get to grips with issues of literary merit and the nature of obscenity. David Strathairn is admirably straight-faced in the role of prosecuting attorney Ralph McIntosh, as he tiptoes through a minefield of sexual imagery and baffling phrases like "angel-headed hipsters". Hamm's tight-lipped defence lawyer brings a sense of intellectual superiority to the proceedings – he's a crusading Don Draper with the added bonus of a moral compass.

Ginsberg himself wasn't on trial here and wasn't present at the proceedings, but the debate about whether the law is an effective tool for censoring and constraining artists remains highly topical. As one of the more thoughtful witnesses (played by Treat Williams) explains, "You can't translate poetry into prose. That's why it is poetry." The poet's own perspective on his life and work is captured in conversation with an off-camera reporter. A bearded, chain-smoking Ginsberg talks openly about his homosexuality, his mother's psychiatric problems, and fellow writer Carl Solomon, to whom "Howl" was dedicated. This strand of the film was inspired by a never-published interview that Ginsberg gave to Time magazine, but the film's dialogue is culled from a variety of sources.

Trying to explain the process of translating feelings into verse is a hard thing to pull off on film. Perhaps that's why most film-makers prefer to concentrate on the broken marriages and substance abuse that go hand in hand with tortured literary geniuses. Epstein and Friedman, who also wrote the screenplay, have done a good job trying to condense biographical detail and literary theory into what is basically a monologue – without being pretentious or boring. Brief flashbacks of Ginsberg pounding away at his typewriter, with his friend Neal Cassady, and in bed with long-term partner Peter Orlovsky, help to round out a portrait of the artist.

The final piece in the jigsaw – the poem – is the most problematic aspect of the film. How much of the work does the audience need to hear, and how do you hold their attention through some long and difficult passages? I quickly became bored of Franco's declamatory style, as he reads to a gathering of smug-looking hipsters at the Six Gallery in San Francisco.

When the recitation continues over Eric Drooker's animation, the effect is even worse. It's a matter of taste whether you thrill to the repeated imagery of fire, the minotaur-like Moloch and weirdly elongated bodies flying across the night sky. I prefer not to have someone else's interpretation of the verse foisted on me. Archive footage from the period would have been another option to fill the gap, but overall I think the poetry should have been used more sparingly.

Howl is bold, stylish attempt to capture a period in the mid-20th century when writing poetry could be an act of political rebellion – a shot across the bows of dull, conformist, heterosexual America. By casting the handsome and charismatic James Franco as Ginsberg, the directors could have turned this into yet another movie about the cult of personality. Instead they've largely succeeded in keeping the focus on the verse and on the act of writing. As the man said, "There's no Beat Generation. Just a bunch of guys trying to get published."

I'm surprised that this film worked as well as it did, and that it has been received as well as it has here. I read Howl about 5 years after Ginsberg wrote it, when I was in high school, and, like it or not, it became part of my thinking in the fifty years since then. Still in high school, I could quote passages from the poem at my friends, who would follow up with the next passage, etc. Boooring. But if you had told me that a film would be made about it, with a script constructed of trial transcripts and interviews in the public record, alternating with a recreation of Ginsberg's first public (paying-public; there was ONE previous reading of the full poem) reading of the poem, I wouldn't have expected much. And I would have been wrong. It's well-done and well-acted, and no excuses are made for anything about Ginsberg or his work. I was dismayed at first to see the poem interpreted into animation, but the filmmakers were savvy enough to produce the animation in the style of the times, i.e., 1955, when Disney's Fantasia was still the state of the art, and the animation in Howl could have come out of the Night on Bald Mountain section. In the end, it worked, I think, by keeping the viewer visually in the world of the poem itself, rather than in the biographical material about Ginsberg or the trial and the litigants. So if you want to watch a movie about a poem, and the poet and his friends, but mainly about the poem, this one does a pretty good job.

Did you know

- TriviaShot in 14 days around New York City in March/April 2009.

- GoofsAbout 29 minutes in, Franco (as Ginsberg) lights up a cigarette. You can clearly see a layer of digital shading (meant to darken Franco's beard) that is overlaid onto his face, esp. his left jaw. This shading also goes over Franco's hand in this scene.

- Quotes

Allen Ginsberg: There's no beat generation. It's just a bunch of guys trying to get published.

- SoundtracksTonight at the Sands

Written by Jack Arel and Jean-Claude Petit (as Jean-Caude Petit)

ZFC Music (ASCAP)

Courtesy of FirstCom Music

- How long is Howl?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box office

- Gross US & Canada

- $617,334

- Opening weekend US & Canada

- $51,185

- Sep 26, 2010

- Gross worldwide

- $1,614,810

- Runtime

- 1h 24m(84 min)

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.85 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content