Adicionar um enredo no seu idiomaIn the woods, a 13-year-old boy is grabbed by an escaped convict and told to bring money later that day. The boy does as he's told, only to be attacked by the convict's partner. A murder ens... Ler tudoIn the woods, a 13-year-old boy is grabbed by an escaped convict and told to bring money later that day. The boy does as he's told, only to be attacked by the convict's partner. A murder ensues, and through happenstance, the murderer and the boy's mother form an alliance. All thi... Ler tudoIn the woods, a 13-year-old boy is grabbed by an escaped convict and told to bring money later that day. The boy does as he's told, only to be attacked by the convict's partner. A murder ensues, and through happenstance, the murderer and the boy's mother form an alliance. All this takes place in four days during which the boy has his first communion, his separated par... Ler tudo

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Artistas

- Prêmios

- 3 indicações no total

- Suzan

- (não creditado)

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Elenco e equipe completos

- Produção, bilheteria e muito mais no IMDbPro

Avaliações em destaque

"Scene of the Crime" has many of the virtues of "Wild Reeds,"--a film that will inhabit you for weeks after you've seen it--chief among them Techine's intelligence and sensitive handling of character and flair for melodrama. If Thomas Hardy were alive today, he'd probably be Techine's script-writer.

The film's two concerns are repression and freedom. Thomas--a sullen angry 13 year old--and Lili--his dreamy, distractedly neurotic mother-- undergo several collisions and unions with a young escaped convict and his friends: they are left to pick up the pieces and reconfigure their lives. Both mother and son are bound by a repressions whose roots are in family, community and religion. And each conflict with others binds them like a rope, so that Thomas futilely lashes out in anger while Lili attempts to lose (and in doing so) find herself with an act of impulsive negation. We could trace much of the repression toward the less likable characters--other criminals or family members--but doing so is futile. Techine understands what Renoir meant when said "everyone has his reasons," and so this film isn't about the difficulty of living with other people, but the difficulty of living in this universe.

Techine has often been called a "novelistic" director; meaning he takes you deep inside his characters' thoughts and motivations. This doesn't involve voiceover, just Techine's direction and the melodramatic plots that force their characters into confrontations ordained by the strength of their passions. Melodrama asks the most of its characters; requires them to feel and undergo all they can. It's numerous coincidences, and run-ins can seem like an amplified version of life's randomness and havoc. Techine's approach involves an analytical acceptance of melodrama's approach to narrative; a willing and measured use of its conventions, resulting in narratives that often seem more vivid than reality and paradoxically more truthful and satisfying. The emotions unearthed are more intense than those brought out by reality, but possess the inner truth of reality.

His technique is not flashy, attention-getting or hyper-formalistic: which means it works discreetly and extremely well. There is an ever-present analytical attention to the natural (and un-) surroundings that surround his characters, along with an intense intimacy toward them. He follows very few rules, and mixes quick cutting with measured long takes and a mobile camera. All this allows us to move back and forth and toward and away from his characters, sympathizing with them in close-up one moment, then judging at a detached angle or pan to another character's reaction. It is a wonderfully effective method, and constantly reminds us of each character's motivations (as do the relentless melodramatics.)

Techine's films aren't formally difficult, but if you lose track at one point it's hard to catch up, because his characters will have accumulated even more motivations and reactions by then. The intense sensitivity of his style allows us to accurately register each character's accumulating layer of emotions, which continually enlarge their motivations. To lose track of that accumulative process is probably what happened to Roger Ebert, who wrote the film should have been a gangster drama made in 1939, so that the melodramatic plot would seem more acceptable and Techine's moments of psychological insights wouldn't seem so "out of place." (The film IS primarily flawed in the sketchiness of the convict's lover and the overly-rushed pace of the climactic sequence.)He doesn't consider that the melodrama of the plot is precisely what allows for those moments of psychological insight. And desire for the film to be an old-fashioned crime noir seems inexplicable, when this is obviously a family drama where crime serves to provoke a shake-up and re-evaluation of family relations and the life-directions the characters have chosen. At the end of "Scene of the Crime" we're not sure whether Thomas and Lili have either recovered or damaged forever. And as Lili hauntingly remarks, after a certain point, losing and finding yourself may be the same process.

Let me make my bias clear: I am an Alfonso Cuarón fan, and his adaptation of Great Expectations remains my favorite. Still, even the subtle nod to Dickens in Téchiné's work had me wishing, "If only Téchiné would direct a Charles Dickens adaptation!"

With assistance from co-writers Pascal Bonitzer and Olivier Assayas (both of whom have since become directors themselves), Téchiné weaves narrative twists that obscure some of the plot's illogical turns, keeping the audience constantly guessing.

Pascal Marti's signature unsettling camera movements and deceptively simple editing style evoke the tension and immediacy of rapid sketches. From the first frame to the last, nearly every scene is imbued with a sense of anticipation and menace. This is a post-New Wave work where human and psychological motivations take precedence over formal innovation, yet it carries the unmistakable traces of New Wave cinema-elements we sorely miss in contemporary French filmmaking.

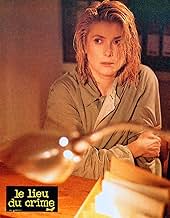

The casting is praiseworthy, particularly Catherine Deneuve, who delivers a subtle and commanding performance, and Nicolas Giraudi, whose portrayal of a lost child searching for a father figure is equally compelling.

Thomas's mother Lili (Catherine Deneuve) runs a club on the lake. After a violent altercation between Martin and his accomplice, an injured Martin goes to the club where he meets Lili. She feels attracted to him and decides to help Martin.

The film is full of nuances. The dynamics between Thomas and his parents, and his grandparents and parents is cleverly and in an understated manner brought to our attention. A good example of that is the strained atmosphere and undercurrents at the grand luncheon held to celebrate Thomas's first communion.

The soundtrack is outstanding too. In one of the scenes in the woods where suspense is reaching breaking point, André Téchiné uses the sound of cicadas and crickets building up to a crescendo to accentuate the tension. A very clever technique indeed.

Cinematography is of the highest quality too.

If there is one thing I will remember, it is the quality of the performances; they all are really good. Special mention must be made of the commanding performances by Catherine Deneuve, and by Danielle Darrieux who plays Thomas's grandmother.

I score this film a high 8/10.

Here Catherine Deneuve stars as Lili Ravenel, who has a 13-year-old son, Thomas (Nicolas Giraudi), who is not doing well at school, a father who no longer cares about people at all, including members of his own family, and a mother who is emotionally close and distant by turns. Lili is estranged from her husband, a man she no longer loves, if ever she did. She is a woman of a certain age who finds diversion in managing a night club. Thus we have the familiar psychology of the bored middle class woman who, we know, will be drawn irresistibly to the excitement of an outsider. Directors who find themselves in the enviable position of directing the beautiful, cool and stately Deneuve seem themselves irresistibly drawn to showing her in compromised situations. I'm thinking of Belle de Jour (1967) and Mississippi Mermaid (1969), directed respectively by Luis Buñuel and Francois Truffaut. In the former Deneuve is a day-tripping prostitute and in the latter she is a criminal on the run. For some odd reason there is something deeply moving about seeing Deneuve give into her baser nature. (I think.)

Anyway, here she does indeed give herself to the rough young man who has killed his companion, and she does so without a hint of regret or lingering doubt. Incidentally in Téchiné's Ma Saison Préférée, mentioned above, there is a scene in which a young intern has his way with Deneuve using much the same approach that Wadeck Stanczack, who plays Martin, an escaped con, employs here. That Lili's sexuality is aroused by his crude demand is the psychology that Téchiné wants to concentrate on; but because one of the weaknesses of his movie is a lack of focus, the impact of her desire is not as strongly felt as it might be. For a most striking and stunning exploration of this theme see Vittoria De Sica's unforgettable The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (1971).

Another weakness of this movie is some unconvincing action and dialogue in places. The opening scene in which Thomas is threatened by Martin who demands money to help him escape is a case in point. Martin's threats seem mild and ineffective. One wonders why Thomas is compelled to return. I also wonder about the boy's response to seeing his mother in bed with Martin. His first reaction is to say, "He will kill you!" and then later he asks his father, "Is that love?", which doesn't seem like something a 13-year-old would say. A six-year-old, maybe. Also a puzzle is why Claire Nebout, who is interesting as Alice, the girl involved with the two escapees, stops her car in the rain to pick up Thomas only to throw him out a few minutes later. Why did she stop at all? As the scene was shot he seemed to be in the middle of the road, so she couldn't avoid him, but considering that it was dark and it was raining, I don't think that would happen. At any rate, the purpose of the scene is to show that Thomas, like his mother, is starved for excitement, begging Alice to take him with her.

My favorite Téchiné movie is Rendez-Vous (1985) starring a very young and vital Juilette Binoche, who is clearly adored by the director. It is, like this movie, uneven in places, but Binoche is incredibly sexy and captivating. If you are a Binoche fan, see it. You will experience a side of her not shown in her American movies.

By the way, when this was filmed Deneuve was about 43-years-old and had already appeared in at least 67 films. She is the kind of woman who grows more beautiful as she grows older. I found her much more attractive here than when I first saw her in the celebrated The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964), released when she was 21.

(Note: Over 500 of my movie reviews are now available in my book "Cut to the Chaise Lounge or I Can't Believe I Swallowed the Remote!" Get it at Amazon!)

Você sabia?

- CuriosidadesThe film underwent an HD restoration in 2018 by Eclair, with the support of Arte France's cinema unit and MK2 Films.

- Erros de gravaçãoWhen Thomas first tries on his suit that "itches", his top shirt button is undone. But when he undresses in his room shortly after that, he undoes that button too.

- Versões alternativasVideo version runs 74 minutes.

- ConexõesFeatured in Danielle Darrieux: Il est poli d'être gai! (2019)

Principais escolhas

- How long is Scene of the Crime?Fornecido pela Alexa

Detalhes

- Data de lançamento

- País de origem

- Idioma

- Também conhecido como

- Scene of the Crime

- Locações de filme

- Auvillar, Tarn-et-Garonne, França(street scenes, hotel, bridge over river)

- Empresas de produção

- Consulte mais créditos da empresa na IMDbPro

Bilheteria

- Faturamento bruto nos EUA e Canadá

- US$ 164.187

- Tempo de duração1 hora 30 minutos

- Mixagem de som

- Proporção

- 2.35 : 1

Contribua para esta página

![Assistir a Bande-annonce [OV]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/M/MV5BMGZlMGQ4MjQtNTJkNC00MmMzLWFhYzgtMjZlNWFmY2NhMGY0XkEyXkFqcGdeQXRyYW5zY29kZS13b3JrZmxvdw@@._V1_QL75_UX500_CR0)