Nachdem der Berufskiller Jef Costello von Zeugen gesehen wird, treiben ihn seine Bemühungen, sich selbst ein Alibi zu verschaffen, weiter in die Enge.Nachdem der Berufskiller Jef Costello von Zeugen gesehen wird, treiben ihn seine Bemühungen, sich selbst ein Alibi zu verschaffen, weiter in die Enge.Nachdem der Berufskiller Jef Costello von Zeugen gesehen wird, treiben ihn seine Bemühungen, sich selbst ein Alibi zu verschaffen, weiter in die Enge.

- Regie

- Drehbuch

- Hauptbesetzung

- Auszeichnungen

- 1 Nominierung insgesamt

Cathy Rosier

- La pianiste

- (as Caty Rosier)

Jacques Léonard

- Garcia

- (as Jack Léonard)

Empfohlene Bewertungen

Melville's masterpiece about a contract killer, a modern day samuraï. He makes brilliant use of the city he loved so much, Paris. The feel, the sounds, the streets, the noise, it's all hauntingly cold and distant but at the same time he makes Paris seem like the coolest city in the world.

In the beginning of the film Melville uses a beautiful static shot of over 4 minutes to establish the audience with a seemingly empty room, then we see smoke circling upwards. There must be someone in the room but it's practically impossible to determine where the smoke is coming from. Finally Jeff Costello gets up from his bed, which wasn't recognizable as such in the first place, and appears on screen. The whole set-up is more reminiscent of a moving replica of a painting by the surrealist Paul Delvaux than anything else in modern cinema. Another surreal set piece is when after his first hit, all possible suspects are brought in at a police station, including Delon himself. Not one by one but all of 'em at the same time. In the next scene we see at least a hundred "gangsters", all wearing trench coats and hats, in a large hall, where they will be interrogated "en plein public". Genuinely strange procedures but handled with such care and stylishness that it becomes completely believable. It gives the somewhat humorous suggestion that the streets of Paris are populated by hundreds, even thousands, of trenchcoat-wearing gangsters, all loners, only seeing each other at card games and occasions like this.

Alain Delon is the perfect embodiment of gangster coolness in this career-defining role as a hit-man in Paris, a modern-day samuraï. "Le Gangster", as the French lovingly call them. Off course, these gangsters don't exist anymore and they probably never existed at all. French Gangsters must have been redefining their look after seeing Delon in this film. His association in real life with French criminal circles, in particular the Marseille underworld, has always given his performances a very strange aura.

As a kid, I regularly visited my grandmother who lived near the city of Marseille and on French television I saw lots of French gangster movies (well, my parents let me watch with them). Alain Delon was in quite a few of them. When I grew older and could identify most of the French screen legends, Delon as no other came to represent the ultimate gangster. An stylized icon of urban cool. I'm also convinced that his character Jef Costello in Le Samouraï was the inspiration for the hissing and whispering fellow in the trench coat in Sesame Street (did he have a name?), something like a gangster, a criminal. A mysterious strange man you should avoid as a kid. I'll be damned if I'm wrong, but I still see Alain Delon in Sesame Street!

In the beginning of the film Melville uses a beautiful static shot of over 4 minutes to establish the audience with a seemingly empty room, then we see smoke circling upwards. There must be someone in the room but it's practically impossible to determine where the smoke is coming from. Finally Jeff Costello gets up from his bed, which wasn't recognizable as such in the first place, and appears on screen. The whole set-up is more reminiscent of a moving replica of a painting by the surrealist Paul Delvaux than anything else in modern cinema. Another surreal set piece is when after his first hit, all possible suspects are brought in at a police station, including Delon himself. Not one by one but all of 'em at the same time. In the next scene we see at least a hundred "gangsters", all wearing trench coats and hats, in a large hall, where they will be interrogated "en plein public". Genuinely strange procedures but handled with such care and stylishness that it becomes completely believable. It gives the somewhat humorous suggestion that the streets of Paris are populated by hundreds, even thousands, of trenchcoat-wearing gangsters, all loners, only seeing each other at card games and occasions like this.

Alain Delon is the perfect embodiment of gangster coolness in this career-defining role as a hit-man in Paris, a modern-day samuraï. "Le Gangster", as the French lovingly call them. Off course, these gangsters don't exist anymore and they probably never existed at all. French Gangsters must have been redefining their look after seeing Delon in this film. His association in real life with French criminal circles, in particular the Marseille underworld, has always given his performances a very strange aura.

As a kid, I regularly visited my grandmother who lived near the city of Marseille and on French television I saw lots of French gangster movies (well, my parents let me watch with them). Alain Delon was in quite a few of them. When I grew older and could identify most of the French screen legends, Delon as no other came to represent the ultimate gangster. An stylized icon of urban cool. I'm also convinced that his character Jef Costello in Le Samouraï was the inspiration for the hissing and whispering fellow in the trench coat in Sesame Street (did he have a name?), something like a gangster, a criminal. A mysterious strange man you should avoid as a kid. I'll be damned if I'm wrong, but I still see Alain Delon in Sesame Street!

This film starts off with the same sound like Sergio Leone's 'C'era un volta il west', but it's just that here the sound is made not by a plate, but a canary, the cold-blooded killer's canary.

This film was made in 1967, the French nouveau vague already apparent all over the place, but with much more subtle undertones than, say, a work by Truffaut.

No, Melville's films were old-school, but at the same time revolutionary, in a delicate way. Take for example the 'chase' scene through the Metro. Practically nothing happens: there are no gunfights, no combat sequences, perhaps just a small chase. But it is Melville's camera and Delon's inimitable performance that keep the audience mesmerized all the way.

The camera practically flirts with the audience throughout the whole movie, picking the most interesting angles and achieving so much practically without any effort. Delon's character changes his expression only once or twice during the movie, shoots faster than even Leone's gunslingers and never forgets to feed his canary. To me, one of the most accomplished antiheroes of the whole genre.

The dialogue is barely there, but when it is, then it's something you'd probably wish you would have come up with yourself. It is a minimalist work that achieves the absolute maximum. Simply put: one of the best crime noirs ever made.

This film was made in 1967, the French nouveau vague already apparent all over the place, but with much more subtle undertones than, say, a work by Truffaut.

No, Melville's films were old-school, but at the same time revolutionary, in a delicate way. Take for example the 'chase' scene through the Metro. Practically nothing happens: there are no gunfights, no combat sequences, perhaps just a small chase. But it is Melville's camera and Delon's inimitable performance that keep the audience mesmerized all the way.

The camera practically flirts with the audience throughout the whole movie, picking the most interesting angles and achieving so much practically without any effort. Delon's character changes his expression only once or twice during the movie, shoots faster than even Leone's gunslingers and never forgets to feed his canary. To me, one of the most accomplished antiheroes of the whole genre.

The dialogue is barely there, but when it is, then it's something you'd probably wish you would have come up with yourself. It is a minimalist work that achieves the absolute maximum. Simply put: one of the best crime noirs ever made.

I just recently saw this film for the first time (a la Criterion) and I was completely blown away. This film can be summed up with a single word: minimalism.

This is a work of true cinema. Hollywood tends to forget that cinema is first and foremost a visual art. Le Samurai is a film that could've been made as a silent movie. The director establishes meaning not with dialog but with the best tools available to a director; editing, mise en scenes, cinematography and composition. There is a constant feeling of solitude and isolation. Even when the protagonist finds himself in large groups, his face is pale, his eyes are cast downward and he is still a constant outsider.

On another note, the film looks surprisingly modern. There's none of the graininess of many other 60s and 70s films. Rather, the lighting and the whole visual aesthetic is pitch perfect, from the black and white nightclub (dualism) to the sparse gray apartment to the subterranean eeriness of the Paris subway.

Personally, I would not recommend this film to people not interested in real cinema, people who like 'movies' rather than 'film', simply because there's a strong possibility it will seem extremely annoying and boring to you. On the other hand, if you're a fan of serious cinema, do yourself a favor and watch this film.

This is a work of true cinema. Hollywood tends to forget that cinema is first and foremost a visual art. Le Samurai is a film that could've been made as a silent movie. The director establishes meaning not with dialog but with the best tools available to a director; editing, mise en scenes, cinematography and composition. There is a constant feeling of solitude and isolation. Even when the protagonist finds himself in large groups, his face is pale, his eyes are cast downward and he is still a constant outsider.

On another note, the film looks surprisingly modern. There's none of the graininess of many other 60s and 70s films. Rather, the lighting and the whole visual aesthetic is pitch perfect, from the black and white nightclub (dualism) to the sparse gray apartment to the subterranean eeriness of the Paris subway.

Personally, I would not recommend this film to people not interested in real cinema, people who like 'movies' rather than 'film', simply because there's a strong possibility it will seem extremely annoying and boring to you. On the other hand, if you're a fan of serious cinema, do yourself a favor and watch this film.

For once, a bad guy who really acts like a bad guy should! This hit-man is one cold, non-descript and calculating man who plans and executes his hit with the utmost precision. About the only character I remember who did a more thorough job was the hit-man in Day of the Jackal. The police also seem very bright and competent--and repeatedly nearly trip up the baddie (Jef). Because of all this realism, I strongly commend this movie. On top of the realism, I really liked the ending. All in all, a fine film and there are no negatives that I can think of--except that this type of film is probably NOT everyone's cup of tea, so to speak. There really isn't any romance and no one is particularly likable, but what do you expect in a film like this?

The film begins with a preface : 'Il n'y' a pas plus profound solitude que Celelle samurai Si Ce Nést Celle Dún Tigre Dans la jungle..Peut-etre..'Le Bushido. Samurai's solitude is only comparable a tiger into jungle . Stars Jef Costello (Alain Delon as excellent anti-hero) is a cold professional killer , he establishes an alibi with the help his lady-lover (Nathalie Delon) and unexpectedly in an act of almost unknown compassion by a club's piano player (Rosier). Meanwhile , he's double-crossed and an obstinate police inspector (Francois Perier) track him down . The precise murderer is pursued throughout the Paris'underground . Then the doomed Costello becomes an avenging angel of death seeking for vengeance.

This is the best of Melville's thrillers with magnificent Alain Delon as the expressionless murderous . Delon has striven in vain to repeat this success in numerous subsequent movies at the same genre , similar others known actors as Lino Ventura , Jean Paul Belmondo and generally directed by Henri Verneuil , Jose Giovanni and Jacques Deray . The movie packs a splendid cinematography by Henri Decae , the photography glitters as metallic and cold as a gun barrel . The picture was perfectly directed by Jean Pierre Melville , giving a memorable work . Later his beginning as a post-war forerunner of the 'Nouvelle vague' , he left his style in several different ways as a purveyor of a certain kind of noir movie , creating his own company and a tiny studio . Although retaining its essential French touch and developing a style closer to the world of the American film Noir of the 1940s than any of their other such foray s. Dealing with character-studio about roles damned to inevitable tragedies , powerful finale , stylized set pieces heightens the suspense and tension have place all around the Melville's filmmaking . His movies and singular talent are very copied and much-admired by contemporary directors, specially the 'Polar' or noir French cinema , such as : 'Second breath' , 'The red circle', 'Dirty money' and , of course , 'Le samurai'.

This is the best of Melville's thrillers with magnificent Alain Delon as the expressionless murderous . Delon has striven in vain to repeat this success in numerous subsequent movies at the same genre , similar others known actors as Lino Ventura , Jean Paul Belmondo and generally directed by Henri Verneuil , Jose Giovanni and Jacques Deray . The movie packs a splendid cinematography by Henri Decae , the photography glitters as metallic and cold as a gun barrel . The picture was perfectly directed by Jean Pierre Melville , giving a memorable work . Later his beginning as a post-war forerunner of the 'Nouvelle vague' , he left his style in several different ways as a purveyor of a certain kind of noir movie , creating his own company and a tiny studio . Although retaining its essential French touch and developing a style closer to the world of the American film Noir of the 1940s than any of their other such foray s. Dealing with character-studio about roles damned to inevitable tragedies , powerful finale , stylized set pieces heightens the suspense and tension have place all around the Melville's filmmaking . His movies and singular talent are very copied and much-admired by contemporary directors, specially the 'Polar' or noir French cinema , such as : 'Second breath' , 'The red circle', 'Dirty money' and , of course , 'Le samurai'.

Alain Delon's Top 10 Films, Ranked

Alain Delon's Top 10 Films, Ranked

To celebrate the life and career of Alain Delon, the actor often credited with starring in some of the greatest European films of the 1960s and '70s, we rounded up his top 10 movies, ranked by IMDb fan ratings.

Wusstest du schon

- WissenswertesWhen Jean-Pierre Melville brought a copy of the script to Alain Delon, Delon asked him what the title was. When he was told the title was "Le samouraï", Delon had Melville follow him to his bedroom, where there was only a leather couch and a samurai blade hanging on the wall. Melville had written the screenplay with Delon expressly in mind for the lead.

- PatzerThe streets change from bone dry to soaking wet and raining when Jef flees from the female undercover cop in the Paris Metro.

- Zitate

[hitman enters the room of the bar owner]

Martey, Nightclub Owner: Who are you?

Jeff Costello: Doesn't matter.

Martey, Nightclub Owner: What do you want?

Jeff Costello: To kill you.

[shoots him]

- Crazy CreditsThe movie's Opening Credits include an epigraph: " "There is no solitude greater than a samurai's, unless perhaps it is that of a tiger in the jungle." - The Book of Bushido."

- Alternative VersionenThe West German theatrical version was cut by approximately eight minutes.

- VerbindungenFeatured in Zomergasten: Folge #10.3 (1997)

- SoundtracksLe Samouraï

Written and Performed by François de Roubaix Et Orchestre

Top-Auswahl

Melde dich zum Bewerten an und greife auf die Watchlist für personalisierte Empfehlungen zu.

Details

- Erscheinungsdatum

- Herkunftsländer

- Sprache

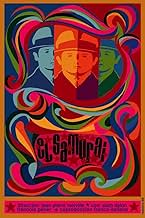

- Auch bekannt als

- El samurai

- Drehorte

- Produktionsfirmen

- Weitere beteiligte Unternehmen bei IMDbPro anzeigen

Box Office

- Bruttoertrag in den USA und Kanada

- 216.696 $

- Eröffnungswochenende in den USA und in Kanada

- 14.899 $

- 31. März 2024

- Weltweiter Bruttoertrag

- 343.363 $

- Laufzeit

- 1 Std. 45 Min.(105 min)

- Seitenverhältnis

- 1.85 : 1

Zu dieser Seite beitragen

Bearbeitung vorschlagen oder fehlenden Inhalt hinzufügen

![Bande-annonce [OV] ansehen](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/M/MV5BY2YwZTkyOWYtNjU4My00NmVjLWE4ZjMtZTdmZDMyMzJlMjk0XkEyXkFqcGdeQUlNRGJWaWRlb1RodW1ibmFpbFNlcnZpY2U@._V1_QL75_UX500_CR0)