IMDb-BEWERTUNG

6,9/10

6035

IHRE BEWERTUNG

Füge eine Handlung in deiner Sprache hinzuA mystery novel-loving American tourist witnesses a murder in Rome, and soon finds herself and her suitor caught up in a series of killings.A mystery novel-loving American tourist witnesses a murder in Rome, and soon finds herself and her suitor caught up in a series of killings.A mystery novel-loving American tourist witnesses a murder in Rome, and soon finds herself and her suitor caught up in a series of killings.

- Auszeichnungen

- 1 Gewinn & 1 Nominierung insgesamt

Letícia Román

- Nora Davis

- (as Leticia Roman)

- …

Walter Williams

- Dr. Alessi

- (as Robert Buchanan)

Giovanni Di Benedetto

- Professor Torrani

- (as Gianni De Benedetto)

Dante DiPaolo

- Andrea Landini

- (as Dante Di Paolo)

Mario Bava

- Uncle Augusto

- (Nicht genannt)

Geoffrey Copleston

- Asylum employee

- (Nicht genannt)

Adriana Facchetti

- Woman in Sguattera Restaurant

- (Nicht genannt)

Empfohlene Bewertungen

La Ragazza Che Sapeva Troppo/The Girl who Knew too Much(1963) is the first of the giallo genre that didn't blossom until the late 1960s. Also the final film by Mario Bava to be done in black and white. Although a Giallo, the film follows the plot lines of the more traditional mystery story with a few twists. The film that uses the perverse and violent elements of the Gialli or Giallo is Blood & Black Lace(1964). Mario Bava's next film, Blood and Black Lace(1964) is less interested in story and more interested in mood and style. The plot involves a woman who misinterprets the meaning of a murder she witnesses. The first horror picture that John Saxon was in.

Bava in a rare instance uses naturalistic lighting. Usually the lighting in a Bava film is drenched in artful color. The only other film by Mario Bava to use naturalistic lighting is Rabid Dogs(1974). Lacks the sex and violence that dominates the gialli novels. The director was fascinated by the deception of appearences in this film and in his entire filmography. He seemed to have little optimism about human behavior or human nature. There are only three murders that occur in the film while the others happen before the story begins.

The Girl who Knew Too Much(1963) deals with Bava's favorite theme of greed. The murderer before being overcome with bloodlust does these deeds because of obsession with money. Greed is the seed of destruction for the characters in Blood & Black Lace(1964), A Bay of Blood(1971), and Rabid Dogs(1974). Part Alfred Hitchcock and part Edgar Wallace. The acting in the film is good. Leticia Roman is excellent as the naive and attractive Nora Davis. Mario Bava was not interested in doing the film but due to money reason directed it anyway.

Downplays the romantic subplot involving Nora Davis and Dr. Marcello Bassi. The scenes that uses suggestions of drug use were cut for the USA release. I love the scene where Nora sets up a booby trap to catch the murderer with disasterous results. The camera was in love with the figure of Leticia Roman during the scene at the beach while panning from her face to her feet. The short love scene between Nora and Marcello has a short spurt of eroticism. One of the writers who worked on the film was Django director, Sergio Corbucci. John Saxon does some fine acting as the leading man.

Mario Bava and John Saxon did not get along due to many misunderstandings during filming. The director it seems didn't think too highly of actors or actresses. Dante Dipaolo plays the newspaper reporter with sympathy. The use of the tape recorder by the murderer is cleaver. Valentina Cortese gets the top acting honors as the mysterious Laura Terrani. The discovery of the murderer is one of the film's main highlights. Impressed Dario Argento when he did The Bird with the Crystal Plumage(1969) and thus being responsible for the longevity and success of the Giallo in Italy.

Bava in a rare instance uses naturalistic lighting. Usually the lighting in a Bava film is drenched in artful color. The only other film by Mario Bava to use naturalistic lighting is Rabid Dogs(1974). Lacks the sex and violence that dominates the gialli novels. The director was fascinated by the deception of appearences in this film and in his entire filmography. He seemed to have little optimism about human behavior or human nature. There are only three murders that occur in the film while the others happen before the story begins.

The Girl who Knew Too Much(1963) deals with Bava's favorite theme of greed. The murderer before being overcome with bloodlust does these deeds because of obsession with money. Greed is the seed of destruction for the characters in Blood & Black Lace(1964), A Bay of Blood(1971), and Rabid Dogs(1974). Part Alfred Hitchcock and part Edgar Wallace. The acting in the film is good. Leticia Roman is excellent as the naive and attractive Nora Davis. Mario Bava was not interested in doing the film but due to money reason directed it anyway.

Downplays the romantic subplot involving Nora Davis and Dr. Marcello Bassi. The scenes that uses suggestions of drug use were cut for the USA release. I love the scene where Nora sets up a booby trap to catch the murderer with disasterous results. The camera was in love with the figure of Leticia Roman during the scene at the beach while panning from her face to her feet. The short love scene between Nora and Marcello has a short spurt of eroticism. One of the writers who worked on the film was Django director, Sergio Corbucci. John Saxon does some fine acting as the leading man.

Mario Bava and John Saxon did not get along due to many misunderstandings during filming. The director it seems didn't think too highly of actors or actresses. Dante Dipaolo plays the newspaper reporter with sympathy. The use of the tape recorder by the murderer is cleaver. Valentina Cortese gets the top acting honors as the mysterious Laura Terrani. The discovery of the murderer is one of the film's main highlights. Impressed Dario Argento when he did The Bird with the Crystal Plumage(1969) and thus being responsible for the longevity and success of the Giallo in Italy.

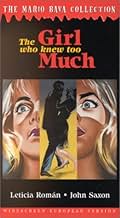

The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1963)

Well, this is a classic worth watching for film buffs interested in the first giallo movie ever made (if we ignore the Hitchcock precedents). Giallo films are purposely simple and gory and filled with dramatic camera-work. In a sense they play off the style, one after another, becoming increasingly about the genre rather than movies that stand on their own. It's like slasher films these days, or maybe even zombie films, where you watch knowing what you're going to get, and that's exactly what you want.

Even the director, Mario Bava, admitted openly this was a silly film with great cinematography. That sums it up. He couldn't even remember the two leading actors. There is a bizarre, cheesy, low-budget thriller aspect to the whole enterprise that makes it fun in a campy way even if you aren't a giallo fan. But it's not good in a traditional sense.

Even the main premise is old as the hills--a serial killer is stabbing women in the back in alphabetical order by last name. This is oddly confused in the plot, because woman C was killed a decade before and we see the next woman killed before our eyes. But the heroine's last name begins with D, as if she is going to be next, and indeed she finds her picture in a file at the end suggesting she really is next in line. So what letter did the woman killed before our eyes have?

One of the weird aspects to the plot might explain this--the woman accidentally smokes a marijuana cigarette at the beginning of the movie, and we come to realize she might have dreamed the whole episode. Never mind there are other deaths and mishaps that seem rather real. And a handsome Italian doctor in love with her.

It's also weird in a funny way that the lead woman is an Italian actress playing an American visitor in Rome. Naturally her Italian is excellent. And the whole movie is centered around the Spanish Steps, which are often completely (completely) empty, not a person around. Adds to the surrealism. There are creaky horror film conventions like the shadowy man seen through the window, or the overdecorated house with creepy lights where the woman is staying, alone of course.

What's to recommend this? The photography. The noir influence (and the Roger Corman one, I suppose) is clear. And beautiful. Now if the story and acting made some modicum of sense we'd be set for a classic over-the-top scary movie. Yes, it's important as a giallo example, but don't overblow the result.

Well, this is a classic worth watching for film buffs interested in the first giallo movie ever made (if we ignore the Hitchcock precedents). Giallo films are purposely simple and gory and filled with dramatic camera-work. In a sense they play off the style, one after another, becoming increasingly about the genre rather than movies that stand on their own. It's like slasher films these days, or maybe even zombie films, where you watch knowing what you're going to get, and that's exactly what you want.

Even the director, Mario Bava, admitted openly this was a silly film with great cinematography. That sums it up. He couldn't even remember the two leading actors. There is a bizarre, cheesy, low-budget thriller aspect to the whole enterprise that makes it fun in a campy way even if you aren't a giallo fan. But it's not good in a traditional sense.

Even the main premise is old as the hills--a serial killer is stabbing women in the back in alphabetical order by last name. This is oddly confused in the plot, because woman C was killed a decade before and we see the next woman killed before our eyes. But the heroine's last name begins with D, as if she is going to be next, and indeed she finds her picture in a file at the end suggesting she really is next in line. So what letter did the woman killed before our eyes have?

One of the weird aspects to the plot might explain this--the woman accidentally smokes a marijuana cigarette at the beginning of the movie, and we come to realize she might have dreamed the whole episode. Never mind there are other deaths and mishaps that seem rather real. And a handsome Italian doctor in love with her.

It's also weird in a funny way that the lead woman is an Italian actress playing an American visitor in Rome. Naturally her Italian is excellent. And the whole movie is centered around the Spanish Steps, which are often completely (completely) empty, not a person around. Adds to the surrealism. There are creaky horror film conventions like the shadowy man seen through the window, or the overdecorated house with creepy lights where the woman is staying, alone of course.

What's to recommend this? The photography. The noir influence (and the Roger Corman one, I suppose) is clear. And beautiful. Now if the story and acting made some modicum of sense we'd be set for a classic over-the-top scary movie. Yes, it's important as a giallo example, but don't overblow the result.

With The Girl Who Knew Too Much, director Mario Bava planted the seed that would evolve into the sub-genre known as the giallo. In fairness, it doesn't much resemble the films that would typify this genre in the 70's. Bava's next film Blood and Black Lace would truly be the definitive template film that would inform the giallo. But there is no doubting that some of the recurring motives and ideas of this most Italian film genre began here.

As the title suggests, The Girl Who Knew Too Much is indebted to Alfred Hitchcock more than anything else. The idea of an innocent thrust into the middle of a deadly situation is one Hitchcock used many times. While the romantic sub-plot and moments of light comedy also recall his work. These latter two elements are mainly what mark out TGWKTM as a cross-over film, as they are certainly not features of giallo cinema as it would develop. But the light, comic approach is one of the things that make this one of the most playful and upbeat films that Mario Bava ever made. Unlike his three other gialli, this film actually has sympathetic characters. While it doesn't have the melodramatic tendencies that those ensemble movies had either. The approach is much more restrained, with a fairly simple amateur sleuth narrative being the framework. Completely different too is the black and white aesthetic. Bava is of course rightfully famous for his masterful use of colour but in this film he shows that his use of light and contrast is just as impressive. This is a very handsome looking movie. Letícia Román adds to this aesthetic too of course, seeing as she is a very beautiful woman. Visually, this is a terrific film. Story-wise, it's certainly less interesting. The fairly mechanical plot is sufficient enough in taking us from A to B but it isn't particularly memorable. But it does introduce some of the motives that would go on to form an important part of giallo cinema such as the convoluted mystery, the bizarre reasoning for murder and the importance of optical subjectivity as well as the focus on style over substance.

The Girl Who Knew Too Much is a film that should be seen by fans of Mario Bava as well as dedicated students of all things giallo. It's a film that is as breezy and light as the genre ever got. It's a lovely and beautiful looking flick from a master film-maker.

As the title suggests, The Girl Who Knew Too Much is indebted to Alfred Hitchcock more than anything else. The idea of an innocent thrust into the middle of a deadly situation is one Hitchcock used many times. While the romantic sub-plot and moments of light comedy also recall his work. These latter two elements are mainly what mark out TGWKTM as a cross-over film, as they are certainly not features of giallo cinema as it would develop. But the light, comic approach is one of the things that make this one of the most playful and upbeat films that Mario Bava ever made. Unlike his three other gialli, this film actually has sympathetic characters. While it doesn't have the melodramatic tendencies that those ensemble movies had either. The approach is much more restrained, with a fairly simple amateur sleuth narrative being the framework. Completely different too is the black and white aesthetic. Bava is of course rightfully famous for his masterful use of colour but in this film he shows that his use of light and contrast is just as impressive. This is a very handsome looking movie. Letícia Román adds to this aesthetic too of course, seeing as she is a very beautiful woman. Visually, this is a terrific film. Story-wise, it's certainly less interesting. The fairly mechanical plot is sufficient enough in taking us from A to B but it isn't particularly memorable. But it does introduce some of the motives that would go on to form an important part of giallo cinema such as the convoluted mystery, the bizarre reasoning for murder and the importance of optical subjectivity as well as the focus on style over substance.

The Girl Who Knew Too Much is a film that should be seen by fans of Mario Bava as well as dedicated students of all things giallo. It's a film that is as breezy and light as the genre ever got. It's a lovely and beautiful looking flick from a master film-maker.

The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1963) is director Mario Bava's gleeful homage to Hitchcock; and one of the earliest examples of the Italian Giallo sub-genre of horror/suspense cinema that would go on to inspire an entire generation of horror filmmakers throughout the subsequent two decades. If you're at all familiar with the work of director Dario Argento for example, then you can see the roots of films like The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970), Deep Red (1975) and Tenebrae (1982) already being established by the skillful blending of low-key thrills, character development and good old fashioned murder mystery, as captured by Bava in this excellent, slow-burning suspense piece. Although it may take some viewers a while to settle into the overall tone of the film - with those first few scenes presenting us with a veritable bombardment of information, both narrative and thematic, before the first murder has even taken place - the eventual unravelling of the plot, and Bava's excellent direction eventually draw us deeper into a story that is here punctuated by a charmingly romantic subplot, a miniature travelogue around the tourist traps of Rome, some subtle moments of almost slapstick humour, and the director's always inventive use of visual experimentation.

The usual Gialli trademarks are already beginning to take shape here, with the film focusing on a foreigner - in this case, twenty-year old American student Nora Davis - who travels to Rome to visit her ailing aunt and inadvertently witnesses a murder. Alongside this central plot device, which would be utilised by Argento in many of his greatest films, such as the three aforementioned, we also have the ideas of sight and perception; with the central protagonist unintentionally witnessing something that is shrouded in elements of doubt and abstraction, and thus having to prove what she saw to sceptical police officers and those nearest to her. Bava's film is also given a neat touch of self-referential sub-text; opening with a shot of the central character herself reading a Giallo murder mystery, casting some doubt as to whether or not the film plays out in the literal sense, or whether it is a merely a constructed reality, taking place in her own mind as she reads the book to herself. This is a thread of interpretation that is examined throughout by the filmmaker, with the title of the book itself, "The Knife", having an importance on the plot that perhaps surreptitiously suggest some element of imagined fantasy.

Once we get through those hectic opening sequences, which introduce the characters and a number of potential sub-plots that are essentially window-dressing to throw us off the trail, the film settles into the murder mystery aspect and the burgeoning relationship between Nora and her young doctor friend, Marcello Bassi. Through the relationship, Bava introduces a subtle comment on the Holmes vs. Watson partnership recast as a romantic dilemma, whilst also creating space within his story to let the audience catch up and think about the potential clues already collected in order to lead us to the eventual discovery of the killer's identity. The use of sight and Bava's directorial slight-of-hand is used meticulously for the initial murder sequence; with the director creating a literal feeling of hazy disconnection and a distorted perspective through a somewhat dated visual effect and the always masterful use of light and shadow. Although the actual effect - which replicates the look of ripples on a pond - might lead a more contemporary audience to giggle or cringe, it does tie in with the continual use of water-symbolism in Bava's work, from the final story in The Three Faces of Fear/Black Sabbath (1963), and A Bay of Blood (1971) most famously, as well as a somewhat cheap gag about marijuana cigarettes that will pay off in the film's closing moments.

Again, the use of humour taps into the spirit of Hitchcock, with intrigue, voyeurism, suspense and murder being reduced to mere complications in the continual romantic wooing of Nora by the charming Dr. Bassi. Nevertheless, the thriller aspects are what we remember most clearly; with Bava's always atmospheric direction, iconography and ability to create tension from the slightest movement of the camera. Once the credits have rolled, we release just how subtle much of Bava's use of sight and perception actually was; with a number of scenes leading on from a moment of confusion by the central character, in which she thinks she sees something that turns out to be nothing of the sort. Again, it shows the director playfully undermining the central character; presenting Nora as someone unable to trust her own eyes, and thus, unable to be trusted with the ultimate unravelling of the plot. Nonetheless, Bava also succeeds in throwing us into this enigmatic mystery; undermining our own perspective of the story by showing us important information early on, allowing us to feel superior to Nora with our benefit of a forewarning, only to then cast further doubt in our mind as the gallery of suspects mount up.

Though still something of a minor work for Bava, The Girl Who Knew Too Much is undoubtedly great; enlivened by the fine performances from the two leads, John Saxon (a cult actor with an impeccable list of credits) and the delightful Leticia Roman (I'm honestly quite smitten), and absolutely brimming with style and energy. The gag at the end is in-keeping with Bava's work, but certainly doesn't lessen the impact of the more thrilling scenes that came before, or the air of grand mystery and excitement suggested by his excellent approach to editing, cinematography and design. Beware that the film also exists under the title The Evil Eye; re-edited by Bava for the American market as more of a light-hearted romp (Tarantino calls it's a masterpiece). The version reviewed here is the original Italian version, a minor masterpiece of Giallo thrills, cinematic abstractions and an old-fashioned approach to storytelling that grips us from the start and never lets us go.

The usual Gialli trademarks are already beginning to take shape here, with the film focusing on a foreigner - in this case, twenty-year old American student Nora Davis - who travels to Rome to visit her ailing aunt and inadvertently witnesses a murder. Alongside this central plot device, which would be utilised by Argento in many of his greatest films, such as the three aforementioned, we also have the ideas of sight and perception; with the central protagonist unintentionally witnessing something that is shrouded in elements of doubt and abstraction, and thus having to prove what she saw to sceptical police officers and those nearest to her. Bava's film is also given a neat touch of self-referential sub-text; opening with a shot of the central character herself reading a Giallo murder mystery, casting some doubt as to whether or not the film plays out in the literal sense, or whether it is a merely a constructed reality, taking place in her own mind as she reads the book to herself. This is a thread of interpretation that is examined throughout by the filmmaker, with the title of the book itself, "The Knife", having an importance on the plot that perhaps surreptitiously suggest some element of imagined fantasy.

Once we get through those hectic opening sequences, which introduce the characters and a number of potential sub-plots that are essentially window-dressing to throw us off the trail, the film settles into the murder mystery aspect and the burgeoning relationship between Nora and her young doctor friend, Marcello Bassi. Through the relationship, Bava introduces a subtle comment on the Holmes vs. Watson partnership recast as a romantic dilemma, whilst also creating space within his story to let the audience catch up and think about the potential clues already collected in order to lead us to the eventual discovery of the killer's identity. The use of sight and Bava's directorial slight-of-hand is used meticulously for the initial murder sequence; with the director creating a literal feeling of hazy disconnection and a distorted perspective through a somewhat dated visual effect and the always masterful use of light and shadow. Although the actual effect - which replicates the look of ripples on a pond - might lead a more contemporary audience to giggle or cringe, it does tie in with the continual use of water-symbolism in Bava's work, from the final story in The Three Faces of Fear/Black Sabbath (1963), and A Bay of Blood (1971) most famously, as well as a somewhat cheap gag about marijuana cigarettes that will pay off in the film's closing moments.

Again, the use of humour taps into the spirit of Hitchcock, with intrigue, voyeurism, suspense and murder being reduced to mere complications in the continual romantic wooing of Nora by the charming Dr. Bassi. Nevertheless, the thriller aspects are what we remember most clearly; with Bava's always atmospheric direction, iconography and ability to create tension from the slightest movement of the camera. Once the credits have rolled, we release just how subtle much of Bava's use of sight and perception actually was; with a number of scenes leading on from a moment of confusion by the central character, in which she thinks she sees something that turns out to be nothing of the sort. Again, it shows the director playfully undermining the central character; presenting Nora as someone unable to trust her own eyes, and thus, unable to be trusted with the ultimate unravelling of the plot. Nonetheless, Bava also succeeds in throwing us into this enigmatic mystery; undermining our own perspective of the story by showing us important information early on, allowing us to feel superior to Nora with our benefit of a forewarning, only to then cast further doubt in our mind as the gallery of suspects mount up.

Though still something of a minor work for Bava, The Girl Who Knew Too Much is undoubtedly great; enlivened by the fine performances from the two leads, John Saxon (a cult actor with an impeccable list of credits) and the delightful Leticia Roman (I'm honestly quite smitten), and absolutely brimming with style and energy. The gag at the end is in-keeping with Bava's work, but certainly doesn't lessen the impact of the more thrilling scenes that came before, or the air of grand mystery and excitement suggested by his excellent approach to editing, cinematography and design. Beware that the film also exists under the title The Evil Eye; re-edited by Bava for the American market as more of a light-hearted romp (Tarantino calls it's a masterpiece). The version reviewed here is the original Italian version, a minor masterpiece of Giallo thrills, cinematic abstractions and an old-fashioned approach to storytelling that grips us from the start and never lets us go.

This Bava film (whose title is clearly a nod to Alfred Hitchcock), credited with being the first giallo, was also one I could have watched earlier – having long considered picking up the now-OOP Image DVD, not to mention via a DivX copy I've owned for some time – but thought it best to wait for this definitive edition (complete with a Tim Lucas Audio Commentary).

Anyway, I don't know whether it's because I preceded it with Riccardo Freda's delirious and luridly-colored THE GHOST (1963) or the fact that the film retains an incongruous light touch (and leisurely pace) throughout – including the heroine's ruse to ensnare her stalker by the unlikely methods adopted in the pulp thrillers she avidly reads – but, while I enjoyed it a good deal, it felt to me like an altogether minor work from the maestro! Similarly, the murder sequences – a stylized highlight of later giallos – are pretty mild here. Still, Bava's consistent virtues – as a director – for creating tremendous suspense and the fantastic lighting and crisp cinematography that come with his intimate knowledge of the camera are well in evidence.

The first half-hour is pretty busy plot-wise, as all sorts of things happen to the charming leading lady (the striking-looking Leticia Roman, daughter of Oscar-winning costume designer Vittorio Nino Novarese): first she gets involved with a drug-dealer, then the old woman she was to live with dies on her, after which she roams outside in a frenzied state to be held up by a small-time crook and witness a knife-murder across Rome's famous Piazza di Spagna! Her disoriented frame-of-mind is effectively rendered by Bava through simple expedients, such as distorting lenses and focus-pulling. Incidentally, the foreigner-investigating-a-series-of-murders-in-Italy plot line prefigures such notable Dario Argento films as THE BIRD WITH THE CRYSTAL PLUMAGE (1970) and DEEP RED (1975). Interestingly, since there was no yardstick for the genre as yet, Bava relied on such familiar film noir trappings as first-person narration to push the story forward.

The film also features a young John Saxon in his first of many "Euro-Cult" outings as Roman's boyfriend and Valentina Cortese as her wealthy, eccentric landlady; the script provides plenty of suspects, but the final revelation comes as a surprise (though, in hindsight, it seems pretty obvious) – and this is followed by a lengthy explanation of the motive behind the killings, which became a standard 'curtain' for this type of thriller. There's an amusing final gag involving a packet of cigarettes and a priest, while Adriano Celentano's catchy pop song "Furore" serves as a motif during the course of the film.

Additional footage was prepared for the U.S. version (snippets of which are present in the accompanying trailer), while the title was changed to THE EVIL EYE and Roberto Nicolosi's score replaced with that of Les Baxter (as had already proved to be the case with Bava's BLACK Sunday [1960])! It would have been nice to have had this cut of the film (which is said to stress the comedy even more) included for the sake of comparison – and it had actually been part of the original announcement for "The Mario Bava Collection Vol. 1", along with the similar AIP variants for BLACK Sunday itself and BLACK SABBATH (1963), but these were subsequently retracted! Incidentally, I now regret not renting the alternate version of THE GIRL WHO KNEW TOO MUCH on DVD-R while I was in Hollywood – but, back then, I wanted first to watch the film as the director intended.

In John Saxon's otherwise entertaining interview on the Anchor Bay DVD (in which he recounts his experience working on this film and other stuff he made during his tenure in Italy), he erroneously mentions that he worked with director Lucio Fulci – whose name he even mispronounces as Luciano! Despite there being a considerable amount of dead air throughout Tim Lucas' Audio Commentary, it does a wonderful job at detailing the film's background – plus offering his own take on events: it does prove enlightening on several aspects of the film I had initially overlooked, such as how the costumes were carefully chosen to define character or the impressive contribution given by Dante di Paolo (George Clooney's uncle!) as the dour journalist investigating the murder spree. Surprisingly, Lucas also mentions that some of Bava's camera moves are more elaborate and graceful as seen in THE EVIL EYE (which makes me want to see it even more!) – but, then, important dialogue stretches heard in the Italian original involving the creepily asexual voice of the killer were bafflingly left out of the American version!!

Anyway, I don't know whether it's because I preceded it with Riccardo Freda's delirious and luridly-colored THE GHOST (1963) or the fact that the film retains an incongruous light touch (and leisurely pace) throughout – including the heroine's ruse to ensnare her stalker by the unlikely methods adopted in the pulp thrillers she avidly reads – but, while I enjoyed it a good deal, it felt to me like an altogether minor work from the maestro! Similarly, the murder sequences – a stylized highlight of later giallos – are pretty mild here. Still, Bava's consistent virtues – as a director – for creating tremendous suspense and the fantastic lighting and crisp cinematography that come with his intimate knowledge of the camera are well in evidence.

The first half-hour is pretty busy plot-wise, as all sorts of things happen to the charming leading lady (the striking-looking Leticia Roman, daughter of Oscar-winning costume designer Vittorio Nino Novarese): first she gets involved with a drug-dealer, then the old woman she was to live with dies on her, after which she roams outside in a frenzied state to be held up by a small-time crook and witness a knife-murder across Rome's famous Piazza di Spagna! Her disoriented frame-of-mind is effectively rendered by Bava through simple expedients, such as distorting lenses and focus-pulling. Incidentally, the foreigner-investigating-a-series-of-murders-in-Italy plot line prefigures such notable Dario Argento films as THE BIRD WITH THE CRYSTAL PLUMAGE (1970) and DEEP RED (1975). Interestingly, since there was no yardstick for the genre as yet, Bava relied on such familiar film noir trappings as first-person narration to push the story forward.

The film also features a young John Saxon in his first of many "Euro-Cult" outings as Roman's boyfriend and Valentina Cortese as her wealthy, eccentric landlady; the script provides plenty of suspects, but the final revelation comes as a surprise (though, in hindsight, it seems pretty obvious) – and this is followed by a lengthy explanation of the motive behind the killings, which became a standard 'curtain' for this type of thriller. There's an amusing final gag involving a packet of cigarettes and a priest, while Adriano Celentano's catchy pop song "Furore" serves as a motif during the course of the film.

Additional footage was prepared for the U.S. version (snippets of which are present in the accompanying trailer), while the title was changed to THE EVIL EYE and Roberto Nicolosi's score replaced with that of Les Baxter (as had already proved to be the case with Bava's BLACK Sunday [1960])! It would have been nice to have had this cut of the film (which is said to stress the comedy even more) included for the sake of comparison – and it had actually been part of the original announcement for "The Mario Bava Collection Vol. 1", along with the similar AIP variants for BLACK Sunday itself and BLACK SABBATH (1963), but these were subsequently retracted! Incidentally, I now regret not renting the alternate version of THE GIRL WHO KNEW TOO MUCH on DVD-R while I was in Hollywood – but, back then, I wanted first to watch the film as the director intended.

In John Saxon's otherwise entertaining interview on the Anchor Bay DVD (in which he recounts his experience working on this film and other stuff he made during his tenure in Italy), he erroneously mentions that he worked with director Lucio Fulci – whose name he even mispronounces as Luciano! Despite there being a considerable amount of dead air throughout Tim Lucas' Audio Commentary, it does a wonderful job at detailing the film's background – plus offering his own take on events: it does prove enlightening on several aspects of the film I had initially overlooked, such as how the costumes were carefully chosen to define character or the impressive contribution given by Dante di Paolo (George Clooney's uncle!) as the dour journalist investigating the murder spree. Surprisingly, Lucas also mentions that some of Bava's camera moves are more elaborate and graceful as seen in THE EVIL EYE (which makes me want to see it even more!) – but, then, important dialogue stretches heard in the Italian original involving the creepily asexual voice of the killer were bafflingly left out of the American version!!

Wusstest du schon

- WissenswertesMario Bava was a big fan of Alfred Hitchcock, and Hitchcockian touches abound in the film, including a cameo by the director. In the scene where Letícia Román is in her bedroom at Ethel's home, the portrait on the wall with the eyes that keep following her is that of Mario Bava.

- PatzerWhen Nora answers the phone in the Torrani house, "hello" is heard before she speaks, even while the receiver is being lifted to her mouth.

- Zitate

Nora Davis: [into the phone] Oh mother, murders don't just happen like that here.

- Alternative VersionenAIP released this as The Evil Eye, a recut version with material used just in some countries out of Italy.

- VerbindungenFeatured in Mario Bava: Maestro of the Macabre (2000)

- SoundtracksFurore

(Appears in the Italian version)

Sung by Adriano Celentano

Written and Composed by Adriano Celentano (as Adicel) and Piero Vivarelli (as Vivarelli)

Published by Edizioni Nazionalmusic and Disco Jolly

Top-Auswahl

Melde dich zum Bewerten an und greife auf die Watchlist für personalisierte Empfehlungen zu.

- How long is The Evil Eye?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Laufzeit1 Stunde 26 Minuten

- Farbe

- Sound-Mix

- Seitenverhältnis

- 1.66 : 1

Zu dieser Seite beitragen

Bearbeitung vorschlagen oder fehlenden Inhalt hinzufügen

Oberste Lücke

By what name was La ragazza che sapeva troppo (1963) officially released in India in English?

Antwort