Füge eine Handlung in deiner Sprache hinzuImmigrant radical Bartolomeo Romagna is falsely condemned and executed for a payroll robbery. Years later, his son Mio sets out to find the truth of the crime and to bring to account the gan... Alles lesenImmigrant radical Bartolomeo Romagna is falsely condemned and executed for a payroll robbery. Years later, his son Mio sets out to find the truth of the crime and to bring to account the gangster Trock Estrella.Immigrant radical Bartolomeo Romagna is falsely condemned and executed for a payroll robbery. Years later, his son Mio sets out to find the truth of the crime and to bring to account the gangster Trock Estrella.

- Regie

- Drehbuch

- Hauptbesetzung

- Für 2 Oscars nominiert

- 4 Gewinne & 4 Nominierungen insgesamt

Murray Alper

- Louie

- (Nicht genannt)

Empfohlene Bewertungen

I like this film. It is an interesting retelling of a point of view regarding one of America's most controversial trials - the 1921 - 1927 legal ordeal of Nicolo Sacco and Bartholomeo Vanzetti for the murder of two men in a payroll robbery in Massachusetts. Both were Italian anarchist immigrants in the U.S. Both were convicted by juries which were local Yankee in make-up, not having any non-Yankees on them. Certainly no Italian Americans. The judge, Webster Thayer, was an openly bigoted man. But thousands of people around the country and the world attacked the verdict, and demanded a retrial. Among those who attacked the trial was George Bernard Shaw, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Sinclair Lewis, Fiorello La Guardia, and (in a move that opened his later great judicial career) Felix Frankfurter. After going through appeals, and the revelations of a fellow prisoner that the payroll robbery was committed by a local criminal gang, the matter was left to a small commission headed by President Lowell of Harvard College. It turned out to be a whitewash. In the end, the two men were electrocuted. Thayer's and Lowell's reputations never recovered from this.

Scholars on the case are still divided on the guilt or innocence of the two defendants - some have suggested they were both railroaded, or that Sacco was more likely to be guilty, but Vanzetti was probably innocent. Today, nearly eighty years after their deaths they still remain a flash point regarding American bigotry. In 1977, on the 50th Anniversary of their deaths, Governor Michael Dukakis formally pardoned both men.

Maxwell Anderson wrote about the subject twice: the play WINTERSET and the play HIGH TOR. Anderson's reputation as a dramatist has been inflated over the years by critics like Brooks Atkinson. He could occasionally write a well done play, but he was not on the level of his contemporary Eugene O'Neill. O'Neill's tragedies (especially his final ones) was based on personal demons from his family and his life. O'Neill was also willing to experiment on stage with masks (THE GREAT GOD BROWN) or with internal counter-dialogs (STRANGE INTERLUDE) or even with trilogies based on Greek originals (MOURNING BECOMES ELECTRA). Anderson only experimented one way - he tried blank verse plays (ELIZABETH THE QUEEN, MARY OF Scotland), and did not do it too well. But here he obviously was passionately determined to defend the memory of the two Italian - American anarchists. His plot is based on developing the thread of the confession (mentioned above) that the murders were planned by a local criminal gang. The gang's leader is Eduardo Cianelli, a brutal criminal who framed the two men by stealing their car as the getaway car.

But the strength of the confession is furthered by claiming the judge was bribed (Thayer was biased but not bribed). Edward Ellis (best recalled as the missing inventor in THE THIN MAN) is the corrupt jurist, who is now a wandering derelict. Vanzetti's famous final letter from the death cell (an elegant final comment that is the basis of contention between Henry Fonda and Eugene Palette in THE MALE ANIMAL) is the basis for the elegant denunciation of the judge in the court by John Carridine (note that his character's first name is also Bartholomeo). Ironically, today, it is believed that elegant final message of Vanzetti may have been written in part by a reporter who supported the defendants.

The son and daughter of the dead men (Burgess Meredith and Margo) are seeking to prove their innocence. But they run against the determination of Cianelli, and his goons. The film is fascinating enough, and concludes satisfactorily (much more than the actual case did). The plot's conclusion also leads to a more prosaic point - if you plan to use a signal to destroy someone, don't forget that signal and use it yourself. See the film to understand that last point.

Scholars on the case are still divided on the guilt or innocence of the two defendants - some have suggested they were both railroaded, or that Sacco was more likely to be guilty, but Vanzetti was probably innocent. Today, nearly eighty years after their deaths they still remain a flash point regarding American bigotry. In 1977, on the 50th Anniversary of their deaths, Governor Michael Dukakis formally pardoned both men.

Maxwell Anderson wrote about the subject twice: the play WINTERSET and the play HIGH TOR. Anderson's reputation as a dramatist has been inflated over the years by critics like Brooks Atkinson. He could occasionally write a well done play, but he was not on the level of his contemporary Eugene O'Neill. O'Neill's tragedies (especially his final ones) was based on personal demons from his family and his life. O'Neill was also willing to experiment on stage with masks (THE GREAT GOD BROWN) or with internal counter-dialogs (STRANGE INTERLUDE) or even with trilogies based on Greek originals (MOURNING BECOMES ELECTRA). Anderson only experimented one way - he tried blank verse plays (ELIZABETH THE QUEEN, MARY OF Scotland), and did not do it too well. But here he obviously was passionately determined to defend the memory of the two Italian - American anarchists. His plot is based on developing the thread of the confession (mentioned above) that the murders were planned by a local criminal gang. The gang's leader is Eduardo Cianelli, a brutal criminal who framed the two men by stealing their car as the getaway car.

But the strength of the confession is furthered by claiming the judge was bribed (Thayer was biased but not bribed). Edward Ellis (best recalled as the missing inventor in THE THIN MAN) is the corrupt jurist, who is now a wandering derelict. Vanzetti's famous final letter from the death cell (an elegant final comment that is the basis of contention between Henry Fonda and Eugene Palette in THE MALE ANIMAL) is the basis for the elegant denunciation of the judge in the court by John Carridine (note that his character's first name is also Bartholomeo). Ironically, today, it is believed that elegant final message of Vanzetti may have been written in part by a reporter who supported the defendants.

The son and daughter of the dead men (Burgess Meredith and Margo) are seeking to prove their innocence. But they run against the determination of Cianelli, and his goons. The film is fascinating enough, and concludes satisfactorily (much more than the actual case did). The plot's conclusion also leads to a more prosaic point - if you plan to use a signal to destroy someone, don't forget that signal and use it yourself. See the film to understand that last point.

From RKO studios in 1936 (though it looks as though it were made in the earliest 30s), during the heyday of the Astaire-Rogers musicals, came something rich and strange. Maxwell Anderson's very serious poetic play was boiled down into a movie that's part Depression-era gangster flick, part Shavian social-issue drama, and part neo-Greek tragedy.

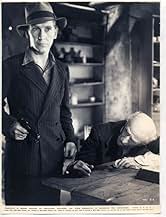

The igniting fuse was the Nicola Sacco/Bartolomeo Vanzetti case of 1927, where two immigrant anarchists were condemned (some would say railroaded) to death supposedly for a robbery in which guards were killed. Anderson pushes it back to 1920 and focuses on a single man, Bartolomeo Romagna (John Carradine), whose auto, filled with anarchist/socialist tracts, is stolen for a similar crime by gangster Eduardo Cianelli. When condemned, Carradine eloquently rebukes the judge (Edward Ellis).

The film now flashes forward to 1936, when Romagna's down-and-out drifter son (Burgess Merdith), spurred by revisionist theories of the case, journeys to New York to confront the surviving principals, including Cianelli, Ellis and a reluctant witness (Paul Guildfoyle). All converge for a reckoning preordained by The Fates....

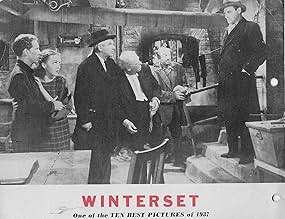

Anderson has heightened his dialogue to lend it immortal aspirations (which may have been a grandiose miscalculation the dominant rhetorical mode of the twentieth century, obvious even by 1936, is flatting). The high-flown posture extends to the look of the film, too a stylized nightscape that's a harbinger of the look of film noir to come a few years later. A low-ceilinged tenement-basement flat is oppressively claustrophobic (markedly so, given the number of actors crammed into it), while the cobblestones and stone arches of the low-rent streets near New York's waterfront glisten wickedly in the pelting rain. (At times the slums look like the central squares of those Transylvanian villages so common in Universal horror pix of this era).

Almost every element of Winterset should seem laughable now but doesn't (though there are a few close shaves). There's an early sequence involving a hurdy-gurdy that lures the slum-dwelling underclass out of its burrows to dance that's hauntingly powerful as is the face of Winterset's love interest, an actress known as Margo, that harks back to the expressiveness of the silents.

The igniting fuse was the Nicola Sacco/Bartolomeo Vanzetti case of 1927, where two immigrant anarchists were condemned (some would say railroaded) to death supposedly for a robbery in which guards were killed. Anderson pushes it back to 1920 and focuses on a single man, Bartolomeo Romagna (John Carradine), whose auto, filled with anarchist/socialist tracts, is stolen for a similar crime by gangster Eduardo Cianelli. When condemned, Carradine eloquently rebukes the judge (Edward Ellis).

The film now flashes forward to 1936, when Romagna's down-and-out drifter son (Burgess Merdith), spurred by revisionist theories of the case, journeys to New York to confront the surviving principals, including Cianelli, Ellis and a reluctant witness (Paul Guildfoyle). All converge for a reckoning preordained by The Fates....

Anderson has heightened his dialogue to lend it immortal aspirations (which may have been a grandiose miscalculation the dominant rhetorical mode of the twentieth century, obvious even by 1936, is flatting). The high-flown posture extends to the look of the film, too a stylized nightscape that's a harbinger of the look of film noir to come a few years later. A low-ceilinged tenement-basement flat is oppressively claustrophobic (markedly so, given the number of actors crammed into it), while the cobblestones and stone arches of the low-rent streets near New York's waterfront glisten wickedly in the pelting rain. (At times the slums look like the central squares of those Transylvanian villages so common in Universal horror pix of this era).

Almost every element of Winterset should seem laughable now but doesn't (though there are a few close shaves). There's an early sequence involving a hurdy-gurdy that lures the slum-dwelling underclass out of its burrows to dance that's hauntingly powerful as is the face of Winterset's love interest, an actress known as Margo, that harks back to the expressiveness of the silents.

Winterset starts out beautifully and profoundly. The story flows well, but the latter scenes are so implausibly constrained that I ended up losing sympathy for the characters. The dialog was hard to make sense of at times, and many of the movie's sequences look like dark scenes from a bad dream... you know, the kind of situation you just can't escape from.

It looks as though, in the transition to turning the stage play into a movie, the makers never gave much thought to overcoming the obvious limitations that the stage imposes on what we now think of as the "action sequences".

I don't regret the time spent watching Winterset. It was interesting, but as a movie (and even allowing for its vintage) it was just "OK".

It looks as though, in the transition to turning the stage play into a movie, the makers never gave much thought to overcoming the obvious limitations that the stage imposes on what we now think of as the "action sequences".

I don't regret the time spent watching Winterset. It was interesting, but as a movie (and even allowing for its vintage) it was just "OK".

The drama itself is interesting to watch in this adaptation of Maxwell Anderson's play, and the themes that it brings out include some particularly weighty ones. The solid cast included at least three performers who were continuing their Broadway roles, and while the production does have a stagy feel at times, it often seems rather appropriate to the material.

The brief prologue shows a political extremist (who is presumably also an immigrant) wrongly accused and executed for a murder committed by a holdup gang. The circumstances are similar to those in some notorious real cases of a slightly earlier era, in which politically unpopular persons were railroaded into convictions because of the public's fear of their beliefs.

The main action starts with Burgess Meredith portraying the executed man's son, now an adult, and determined to get to the bottom of the case despite the obstacles that have come with time. In the course of things, he encounters the judge who had presided over his father's trial, a witness with important information, and a brutal crime boss who is determined to prevent the case from being re-opened. The setup produces some good psychological and ethical tensions, in addition to the drama on the surface.

Most of the supporting cast performs well. John Carradine has a brief role as the father, Margo has a good and important role as a young woman torn between family loyalty and her attraction to Meredith's character, and Eduardo Ciannelli believably portrays the soulless, desperate crime boss. Mischa Auer succeeds in a brief, atypical role as a street agitator. But Edward Ellis gives the best performance, as the judge whose conscience has been tormented ever since the fateful case. The characters and the tragic situation that links them are all effectively portrayed.

The brief prologue shows a political extremist (who is presumably also an immigrant) wrongly accused and executed for a murder committed by a holdup gang. The circumstances are similar to those in some notorious real cases of a slightly earlier era, in which politically unpopular persons were railroaded into convictions because of the public's fear of their beliefs.

The main action starts with Burgess Meredith portraying the executed man's son, now an adult, and determined to get to the bottom of the case despite the obstacles that have come with time. In the course of things, he encounters the judge who had presided over his father's trial, a witness with important information, and a brutal crime boss who is determined to prevent the case from being re-opened. The setup produces some good psychological and ethical tensions, in addition to the drama on the surface.

Most of the supporting cast performs well. John Carradine has a brief role as the father, Margo has a good and important role as a young woman torn between family loyalty and her attraction to Meredith's character, and Eduardo Ciannelli believably portrays the soulless, desperate crime boss. Mischa Auer succeeds in a brief, atypical role as a street agitator. But Edward Ellis gives the best performance, as the judge whose conscience has been tormented ever since the fateful case. The characters and the tragic situation that links them are all effectively portrayed.

I thought Burgess Meredith turned in quite a characterful performance in this otherwise rather dry drama. He is "Mio" whose late father we have already seen at the top of the film being condemned to the chair for his part in a robbery. Now, a generation later he is determined to prove that he was innocent. What quickly becomes apparent is that the investigation at the time was largely based around the "if your face fits" theory, and it doesn't take "Mio" very long to get onto the trail of a far more likely culprit. Meantime, we also discover that a speech made by his dad upon sentencing declaring his innocence and warning the judge that his will be a sort of living death from now on has turned out to be eerily true. That judge (Edward Ellis) has indeed somewhat lost the plot, and is a ghost of his former self wandering the streets with little memory of who he is or was. It might well be that "Mio" could be in a position to salvage more than one should here? The plot clearly seeks to highlight the difficulties for the poverty stricken, slum-dwelling, population of the USA to not just get by in life, but to get a fair hearing from authority. That's not just the court proceedings, but also far more rudimentary aspects of freedom. Even an assembly to dance attracts the police. Ultimately, though, it really does come down to a straightforward style of good and evil, and with the underplayed but effectively sinister effort from Eduardo Ciannelli and a really quite impactful one from Ellis, this can at times be quite a poignant evaluation. Alfred Santelli hasn't done so much to creatively adapt it from the stage though, and that straight transfer to celluloid sees it lose quite a bit of it's intensity. Even with the romantic attachment to "Miriamne" (Margo), much of the intimacy is gone, the dialogue is all too often delivered as if it were set-piece monologues, and none of the characters really come together until very near the end. Just taking it from the theatre to the cinema was always going to compromise some of the nuance, and though this is still a decent effort it just misses a little of the story's soul.

Wusstest du schon

- WissenswertesBurgess Meredith, in his first film with a credited role, recreates the role he played in the original Broadway production.

- VerbindungenFeatured in Sprockets: Masters of Menace (1995)

Top-Auswahl

Melde dich zum Bewerten an und greife auf die Watchlist für personalisierte Empfehlungen zu.

- How long is Winterset?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Erscheinungsdatum

- Herkunftsland

- Sprachen

- Auch bekannt als

- Under New Yorks broar

- Drehorte

- Produktionsfirma

- Weitere beteiligte Unternehmen bei IMDbPro anzeigen

- Laufzeit

- 1 Std. 17 Min.(77 min)

- Farbe

- Seitenverhältnis

- 1.37 : 1

Zu dieser Seite beitragen

Bearbeitung vorschlagen oder fehlenden Inhalt hinzufügen