|

The entrance (north) front of Ferne Park,

the home of Viscountess Rothermere.

Built 2000 to 2002 to designs by Quinlan Terry.

Image via QFT. |

After the sale of

Daylesford (see previous posts on the quintessential Cotswolds country house

here, here, here, and

here) to Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza, was Viscount Rothermere left without a proper country seat? Not for long. Jonathan Harmsworth,

4th Viscount Rothermere (born 1967, son of Vere and Pat "Bubbles" Harmsworth, see earlier post

here), built an exemplary new country house, 2000 to 2002, on the 200 acres known as

Ferne Park.

|

An aerial view of Ferne Park.

Image via QFT. |

The present house is the third that had stood on the site with a view to the Dorset Hills. The second house had been demolished in 1965. The Harmsworths had been looking for a property with views and old out-buildings that could be developed; Ferne Park filled those requirements. The local planning authority had three restrictions that were gladly respected: the house must be built of local stone, be classical in design, and be no larger than the previous house that had occupied the site. As of this writing, Viscount Rothermere spends most of his time at his chateau in the Durdogne where he is visited by his wife and children who otherwise live at Ferne Park.

|

The approach to Ferne Park is on an angle

rather than axial, characteristic of

many Palladian buildings.

Image via QFT. |

Claudia Caroline Clemence Harmsworth, the Viscountess Rothermere, was familiar with the work of classicist English architect

Quinlan Terry who with his son Francis are principals in the firm

Quinlan Francis Terry LLF in Dedham, England; subsequently, the firm was engaged to create a new classical mansion on the property.

One of the inspirational models for the new house was Came House, built in 1754, in Winterborne Came, Dorset. Lady Rothermere thought it an imbalance, however, to have the three smaller upper windows between the engaged columns. So the upstairs windows at Ferne Park are all the same size. (There is no traditional hard-and-fast rule on this, it must be noted. There are other examples of similar houses of the eighteenth-century that also had all the upstairs windows the same size).

|

Came House, Dorset, influenced the

design for Ferne Park.

Image via Wikipedia. |

The house has views to both Dorset and Wiltshire, both having rich resources of building stone. Four different stones were used on the exterior of the house with the slight variations adding to the visual interest.

|

The entrance elevation of Ferne Park.

Photo via QFT. |

The principle stone used for the facades was Chilmark stone, a Jurassic oolitic limestone. In the 13th century, it was used for Salisbury Cathedral; in the 16th century, for Langford Castle; and in the 17th century for Wilton House.

|

The entrance elevation of Ferne Park

showing the subtle variation of stones.

Photo from RADICAL CLASSICISM:

THE ARCHITECTURE OF QUINLAN TERRY |

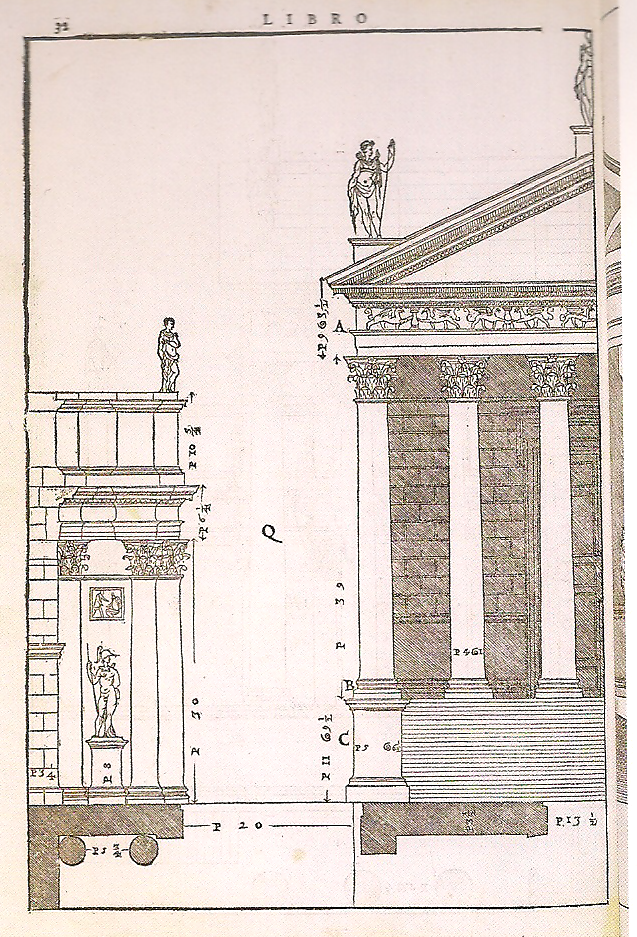

Portland stone, another local Jurassic oolitic limestone, was used for the rusticated basement story, the columns, the entablature, and the chimneys. Andrew Tanser carved the Rothermere coat of arms for the pediment, a feature seen in almost all the houses Palladio illustrated in

Quattro Libri (The Four Books of Architecture).

|

The capitals of the engaged columns

are over 6 feet tall and in the composite style.

Photo via RADICAL CLASSICISM

THE ARCHITECTURE OF QUINLAN TERRY |

|

Quinlan Terry's drawing of the capital

and corner pediment of Palladio's

S.Giorgio Maggiore, Venice, 1564 to 1580,

a model for the capitals at Ferne Park.

Image via RADICAL CLASSICISM

THE ARCHITECTURE OF QUINLAN TERRY

|

|

A detail of the door surround of the main entrance.

Photo from RADICAL CLASSICISM:

THE ARCHITECTURE OF QUINLAN TERRY.

|

|

The Rothermere coat of arms, supporters, and crest

fill the entrance front pediment of Ferne Park.

Photo from RADICAL CLASSICISM

THE ARCHITECTURE OF QUINLAN TERRY.

|

Upper Greensand sandstone, another local stone but of the post-Jurassic period, was also used. This pale green-ish gray stone was used as ashlar in many of the important 18th century Dorset buildings.

|

The long cheek walls of the entrance stairs

was inspired by the Temple of Antionius and Faustina,

Rome, AD 141. From Palladio, I QUATTRO LIBRI, 1570.

Image via RADICAL CLASSICISM:

THE ARCHITECTURE OF QUINLAN TERRY.

|

The fourth stone, not local, was York stone. For durability, it was used for the entrance front staircase and the south terrace paving.

|

The Garden (South) Elevation of Ferne Park.

Photo from RADICAL CLASSICISM:

THE ARCHITECTURE OF QUINLAN TERRY. |

|

Quinlan Terry's drawing of the design

for the south terrace balustrade at Ferne Park.

Image from RADICAL CLASSICISM:

THE ARCHITECTURE OF QUINLAN TERRY.

|

The balusters of the (south) garden terrace utilize a design of alternating forms in order to meet building safety regulations that would prevent a child from falling through. A Baroque rhythm, such as that used at Longhena's Ca' Pesaro in Venice, 1649 to 52, provides an appropriate solution to modern demands on classical architecture.

|

Jonathan and Claudia Harmsworth,

the Viscount and Viscountess Rothermere.

Photo by Francois Halard for Vanity Fair,

November 2006, via Indy Media. |

Although the floor plans were well thought out in terms of proportion and natural light, they might not be suitable to the lifestyles of many American billionaires in terms of expected convenience.

|

A collage of images of Ferne Park by

Francois Halard for Vanity Fair ,

via Indy Media. |

That said, the simplicity of plan does allow some grand Georgian rooms with handsome details. Interior designer

Veere Greeney was brought in early in the design process to help create a comfortable décor compatible with the architecture.

|

Another collage of images of Ferne Park by

Francois Halard for Vanity Fair,

via Indy Media.

|

In an article for Country Life magazine, May 5, 2010, David Watkins writes, "Oil paintings, watercolours, drawings and engravings of an exceptionally wide range of dates and styles, create the impression of a collection that has grown over many years. All the [bathtubs] are old ones that have been refurbished, but there are no coloured marbles or gold taps in the bathrooms, which are plain and discreet."

|

The Entrance Hall of Ferne Park.

Photo via QFT. |

When the house is filled with guests, the Entrance Hall also serves as a Sitting Room. The doorway behind the folding screen leads to the service stairs and, beyond, the Kitchen. On the opposite wall, there is a doorway to a vestibule with a coat closet and powder room, with a sitting room beyond.

|

The Staircase of Ferne Park.

Photo via QFT. |

It is difficult to see in this photo of the stairs, but there are 'Venetian' or 'Palladian' windows, an arched head window flanked by a narrow flat head window, on both the first (main) and second floors at each end, as the house was originally built.

|

The Drawing Room at Ferne Park.

Photo via veeregrenney.com |

The Drawing Room on the center of the south side has a shaped, ornamented plaster ceiling. On either side is a Dining Room (which later became the Breakfast Room) and the Study.

|

Veere Grenney's fabric "Ferne Park."

Photo via Veere Grenney Associates |

No views of the second floor have been published, but this photo of designer Veere Greeney's fabric "Ferne Park" might offer a glimpse. It appears to be the corner of tailored bedhangings, the be-ribboned flat-pleated corner of the canopy in a Georgian room.

(T.D.C.'s note: this detail was later discovered to be from the designer Veere Grenney's own bedroom).

|

The gardens of Ferne Park were designed

by Rupert Golby.

Paul Highnam photo via gardenmuseum.org. |

The gardens, designed by

Rupert Golby, are occasionally open to the public to benefit charities or non-profit organizations. Such was the case on at least two occasions earlier this year.

|

The garden front of Ferne Park

viewed through a gate.

Photo via QFT. |

Check the Events website of the

Garden Museum for the schedule of Garden Open Days for private gardens that are open on behalf of the Garden Museum Development Appeal which supports the creation of the Garden Design Archive. It is an excellent way to visit exceptional properties such as this.

|

Another garden gate view at Ferne Park.

Photo via Southern Spinal Injuries Trust. |

There are several entrances to the estate and one still maintains a carriage entrance for the second house that stood at Ferne Park.

|

Original gateway from the second Ferne Park.

Photo via Images of England. |

Architect Quinlan Terry used the original design as a model for a larger, modern entrance that was an interpretation of the historic precedent.

|

Quinlan Terry's entrance gateway to Ferne Park

based on the design for the previous house.

Photo via Indy Media. |

The outbuildings from the time of the second house were made more picturesque in some instances and renovated to suit modern needs of the family.

|

An outbuilding at Ferne Park that has

been renovated and adapted to modern use.

Photo via MOULDING. |

In 2006, an application was made to extend the main house. Adding a Library on the west and a Dining Room on the east main floor level, plus a Billiard Room and additional service areas on the basement level, the extensions maintained the symmetry and original design concept of the house.

|

The extended garden front at Ferne Park.

Photo from private collection. |

False windows of the north face in the added rooms conceal a fireplace and chimney. Venetian/Palladian windows look out to the garden.

|

The extended east end of Ferne Park

showing the Library addition.

Photo via MOULDING. |

The main house won The Georgian Group award for the Best Modern Classical House in 2003. In 2008, The Georgian Group cited the added Pavilion, also designed by Quinlan and Francis Terry, with the award for Best New Building In The Classical Tradition.

|

The Pavilion at Ferne Park.

A loggia spans this side of the new building.

Photo via The Georgian Group. |

William Kent's Praeneste at Rousham in Oxfordshire was given as the inspiration for the new Pavilion. A seated statue of the influential philosopher Immanuel Kant is placed in the ornamental pool.

|

The Pavilion at Ferne Park.

Photo via MOULDING. |

There has been much speculation in the British Press that the Viscount's French residency status is a scheme to avoid paying British taxes. As there are several other countries that would have a much more favorable tax structure than France, that theory is inconclusive. In any case, the new construction at Ferne Park is a great monument to new classicism in residential design and what can be accomplished with talent, taste, and a lot of money wisely spent in the concentrated effort.