Abstract

The integration of anaerobic digestion (AD) into pulp and paper mill operations presents a sustainable pathway for managing pulp and paper mill sludge (PPMS), a significant waste stream rich in organic matter. However, the process is constrained by the recalcitrant nature of lignocellulosic biomass, nitrogen deficiency, and low buffering capacity—factors that contribute to reduced methane yields and economic infeasibility. This review critically examines over 200 studies to identify key bottlenecks in the AD of PPMS. It evaluates emerging strategies to enhance biodegradability and economic feasibility, including alkaline pretreatment with green liquor dregs, combining primary sludge and secondary sludge, co-digestion with rejected fibers and nutrient-rich substrates, sequential H2 and CH4 production, and biochar addition. The paper also discusses the role of mechanistic and data-driven modeling in optimizing the AD of PPMS and reviews existing techno-economic analysis and life cycle assessment studies documented in the literature. These insights provide a valuable foundation for further research and supporting the practical implementation of AD within the pulp and paper industry.

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

1. Introduction

The pulp and paper industry (PPI) is a major consumer of water (Pokhrel and Viraraghavan 2004), requiring approximately 300–2600 m3 of water per tonne of printing and writing paper produced (van Oel and Hoekstra 2012). Although advancements in water recycling led to more concentrated waste streams, the treatment of wastewater using both physical and biological methods generates a substantial volume of pulp and paper mill sludge (PPMS) (Priadi et al 2014), which represents one of the primary waste streams in the PPI (Gottumukkala et al 2016). In the United States alone, 4–5 million tons of PPMS are produced annually. Traditional landfilling of PPMS results in considerable greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, approximately 2.69 tons of carbon dioxide and 0.24 tons of methane per ton of sludge. Due to strict environmental regulations, public opposition, and increasing disposal costs, the industry is actively pursuing more sustainable approaches for managing PPMS.

PPMS contains 45%–55% organic matter and essential nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, making it a viable substrate for bioenergy and bioproduct generation (Jackson et al 2000). Anaerobic digestion (AD) has emerged as a promising valorization strategy, offering the dual benefits of converting organic waste into biogas and reducing environmental pollution. However, hydrolysis often acts as the rate-limiting step, leading to extended retention times and suboptimal methane yields. This review examines over 200 relevant studies, highlighting key factors influencing biogas production and proposing strategies to overcome these limitations. This analysis offers practical insights for enhancing the commercial feasibility of biogas production from PPMS.

Importantly, this review aligns with the goals of sustainable development and contributes to several united nations sustainable development goals (SDGs). Specifically, it supports SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation) by promoting safe and resource-efficient sludge treatment; SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy) by enhancing the recovery of renewable biogas; SDG 9 (industry, innovation, and infrastructure) through the assessment of innovative AD technologies and modeling approaches; and SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production) by advocating for the circular utilization of industrial waste. Additionally, by addressing the reduction of GHG emissions from conventional sludge management methods, the review contributes to SDG 13 (climate action) (Baltrusaitis et al 2024). These linkages are critical to advancing sustainable solutions within the PPI while ensuring environmental, economic, and social benefits.

2. Pulp and paper processes and different waste streams

The PPI is one of the world’s major industries (Bajpai 2014). In 2023, global pulp production reached 194.75 million metric tons (FAO 2024). This significant production scale also generates approximately 40–70 billion cubic meters of contaminated wastewater annually, which requires proper treatment before discharge into the environment (Badar and Farooqi 2012).

In general, the papermaking process involves two primary stages. Initially, wood pulp is produced from wood chips through a pulping process. The second stage involves the transformation of pulp into paper, followed by any necessary treatments for its final application (Bajpai 2018). In the pulping process, wood chips are broken down into fibers. Chemical processes are the predominant methods for pulping, aiming to extract cellulose from wood. Among these, kraft pulping is the most widely used method, accounting for approximately 80% of total pulp production due to the high strength of the resulting pulps (Biermann 1996, Iglesias et al 2020).

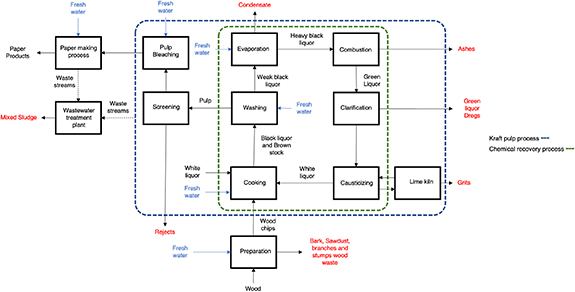

Figure 1 depicts the kraft pulping process and the origin of various waste streams in the PPI. In this operation, wood chips undergo digestion in a cooking unit using ‘white liquor,’ an alkaline solution of sodium sulfide (Na2S) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH), at high temperature and pressure for a few hours (Huber et al 2014). The interaction of lignin with hydroxide and hydrosulfide in this process breaks down lignin into smaller water-soluble fragments, facilitating the separation of cellulose fibers (Kleppe 1970).

Figure 1. Schematic of kraft pulp and paper making process with indication of different waste streams.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageAfter the pulping process, pulp washing operations use process water to remove impurities, such as uncooked chips, and separate cooking liquor from pulp, generating a significant volume of wastewater (Chakar and Ragauskas 2004). Following washing, rejects like barky matter fragments, larger chips, and uncooked chips are removed through screening. These rejects are either recycled into the pulping process or incinerated in the mill’s bark boiler for energy. The screened materials are then directed to the pulp bleaching operation for producing bleached pulp or sent directly to the papermaking operation (Gavrilescu et al 2008, Ashrafi et al 2015, Sharma et al 2020).

In bleaching, the remaining lignin and chromophore groups are removed through oxidation. This occurs in elemental chlorine free or totally chlorine free sequences using agents like ClO2, oxygen peroxide, oxygen, or ozone. Bleaching stages include pulp washing to eliminate solubilized compounds. Despite recycling, this process consumes freshwater and is vital for removing chromophores, leading to a high-load effluent (Huber et al 2014, Sousa et al 2023).

To recycle the chemicals used in the cooking process, a chemical recovery system is crucial during chemical pulping (green dashed line in figure 1). After pulp separation, the dissolved wood with used pulping chemicals forms weak black liquor. This stream is sent to the chemical recovery facility in the mills. The kraft pulping process generates about 10 tons of weak black liquor per ton of pulp (Tran and Vakkilainnen 2008). Dilute black liquor includes lignin, oxidized inorganic chemicals (Na2SO4 and Na2CO3), organic components, and white liquor (Na2S and NaOH) (Bajpai 2015a). The weak black liquor is then processed in the kraft recovery system, where inorganic pulping chemicals are reclaimed, and organic components are burned for energy production in the mill. Evaporators increase the solids content of organics to enhance their heat value.

In the recovery boiler, the combustion of organic components in black liquor generates heat, creating an inorganic smelt enriched with Na2S and Na2CO3, known as green liquor (GL). The addition of a diluted white liquor solution to treat the smelt in the dissolving tank results in the production of GL dregs (GLD) sludge, consisting of solid, undissolved particles (Sewsynker-Sukai et al 2020).

After the recovery boiler, the causticizing process transforms the dissolved Na2CO3 content GL into NaOH. The resulting causticized GL (white liquor) is recycled in the pulping process and returned to the digester. Lime mud (CaCO3) is generated during the causticization process in chemical recovery. It is transferred to a lime kiln and heated to high temperatures to reproduce CaO (Tianzhao et al 2007). The slacker’s white liquor slurry is the source of grits, classified as unreacted lime based on their specific gravity (Kinnarinen et al 2016, Haile et al 2021). Grits, considered solid waste, accumulate in the system and require removal.

2.1. Sludge and advantages of exploiting sludge as a source of cellulose

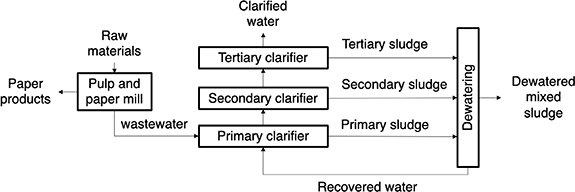

In the PPI, wastewater treatment processes generate organic residue known as sludge (Faubert et al 2016). Figure 2 provides an overview of the wastewater treatment process, identifying primary sources of three common sludge forms. Primary treatments, like neutralization, screening, and sedimentation, remove suspended solids and particulate matter. Secondary biological treatments target biodegradable organic waste, reducing effluent toxicity (Ochoa de Alda 2008). Tertiary treatments, including membrane filtering, UV disinfection, ion exchange, and granular activated carbon, reduce color and further enhance effluent quality (Choi et al 2022). Sludge generation in pulp and paper production varies based on paper grade and the method used. Dewatered sludge from various paper products comprises roughly 20%–40% by dry mass (Haile et al 2021), with primary sludge (PS) constituting 70% of overall sludge (Elliott and Mahmood 2005).

Figure 2. Simplified schematic of paper mill wastewater treatment plant.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageKraft pulp sludge, from the primary clarifier, contains higher cellulose and lower lignin than secondary sludge (SS), making it suitable for biological conversions like fermentation and AD (Migneault et al 2011). The feasible bioconversion of these materials involves breaking down cellulose and hemicellulose polymers into fermentable sugars usable for second-generation biofuels (e.g. biomethane, bioethanol) and biochemicals (e.g. organic acids, bacterial cellulose) (Fatma et al 2018).

Common sludge management practices include landfill disposal, incineration for energy, and land application. These practices can contribute to GHG emissions and environmental concerns when applied to cropland. Paper mill sludges, when discarded in landfills, contribute significantly to the occupation of local landfill space annually. When these sludges are applied to cropland, concerns arise regarding the potential accumulation of trace contaminants in the soil or their runoff into nearby lakes and streams (Bird and Talbert 2008, Bajpai 2015b). Also, a major challenge in using PPMS as fuel is its high water content, necessitating dewatering for efficient incineration with associated costs.

Several studies evaluated PPMS for bioenergy and bioproduct generation using thermochemical and biochemical routes (Gottumukkala et al 2016, Chakraborty et al 2019, Du et al 2020). However, these methods required intensive pretreatment to overcome high ash content, calcium carbonate interference, and chemical residues that hinder enzymatic hydrolysis and microbial activity (Mendes et al 2014). For instance, the production of cellulose nanofiber and nanopaper production from PPMS using organic acid hydrolysis followed by microfluidization demonstrated high yields but remained energy-intensive and costly, limiting its feasibility for large-scale applications (Du et al 2020).

In contrast, AD of PPMS offers a less capital-intensive solution. It can be readily integrated into existing wastewater infrastructure, offering renewable energy recovery without disrupting core mill operations. This approach not only addresses waste management but also enhances the industry’s environmental and economic sustainability (Bajpai 2015a).

3. Microbial conversion of sludge

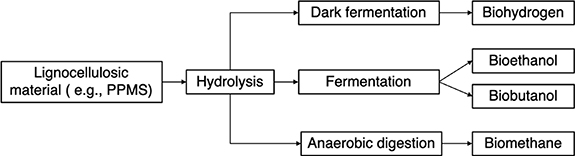

The demand for alternative bioenergy sources is expected to grow significantly due to the rising cost of crude oil and the rising fuel demand. Among the prospective alternative bioenergy resources, lignocellulosic biomass, such as PPMS, has been identified as a promising feedstock for the production of biofuels and other value-added products. The bioconversion of cellulosic components into fermentable sugars is necessary to synthesize industrially significant products. This process is facilitated by cellulolytic microorganisms, including bacteria and fungi, which secrete enzymes to hydrolyze cellulose into glucose monomers.

Cellulose degradation relies on the synergistic action of several enzymes, including endoglucanases, exoglucanases (cellobiohydrolases), and β-glucosidases (Wood and McCRAE 1979). These enzymes are produced by a variety of microorganisms. Fungal species such as Trichoderma reesei, Aspergillus niger, and Clostridium thermocellum (de Vries and Visser 2001, Lynd et al 2002, Bayer et al 2004), and bacterial species such as Cellulomonas fimi and Ruminococcus albus (Walker and Wilson 1991) are notable examples. These microorganisms metabolize glucose via glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway, converting it into pyruvate, which can then enter fermentation pathways to generate bioenergy carriers such as ethanol, hydrogen, or methane (Schink 1997, Lynd et al 2002, Madigan and Martinko 2006).

As illustrated in figure 3, multiple high-value products can be derived from the microbial transformation of PPMS, including biohydrogen via dark fermentation (Clostridium butyricum), bioethanol via yeast fermentation (S. cerevisiae), biobutanol via solventogenesis (Clostridium acetobutylicum), and biomethane via AD (Methanosarcina barkeri) (Balat 2011, Priadi et al 2014, Hay et al 2015).

Figure 3. Biochemical conversion of lignocellulosic material to bioenergy.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageBiohydrogen and biobutanol synthesis from PPMS have been less studied and remain relatively unexplored (Spano et al 1978, Steele et al 2005). In contrast, bioethanol production from PPMS has been relatively well explored at the laboratory scale but faces significant industrial hurdles related to high ash content, water-holding capacity, and viscosity (Branco et al 2018). Despite these challenges, bioethanol benefits from an established production and distribution infrastructure and strong market demand, which enhance its commercial viability. Biomethane production, on the other hand, can utilize nearly all major biomass components (carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins) offering the potential for higher overall conversion efficiency and significant environmental advantages, including effective waste management and reduced GHG emissions (Chandra et al 2012). However, achieving high conversion efficiency in biomethane production strongly depends on successful pretreatment strategies and optimized process conditions (Spano et al 1978, Steele et al 2005).

While several studies evaluated the profitability of bioethanol production from PPMS (Chen et al 2014, Robus et al 2016, Branco et al 2018, Alkasrawi et al 2020), data on the economic viability of biomethane production remain limited. The biogas production method is less mature than fermentation technologies, representing a notable knowledge gap. This underscores the necessity for further research to assess and validate the commercial viability of biomethane production from PPMS.

3.1. AD

Biogas is generated through AD, a process that decomposes organic materials in the absence of oxygen (Adekunle and Okolie 2015). AD has emerged as a promising alternative energy source offering a sustainable option to replace fossil fuels. The PPI is considered well-suited for AD, and integrating proper energy balances into sludge management systems enables the production of high-value biogas. This approach not only minimizes waste but also yields biogas, representing an improvement over traditional biological treatment methods (Kamali et al 2016).

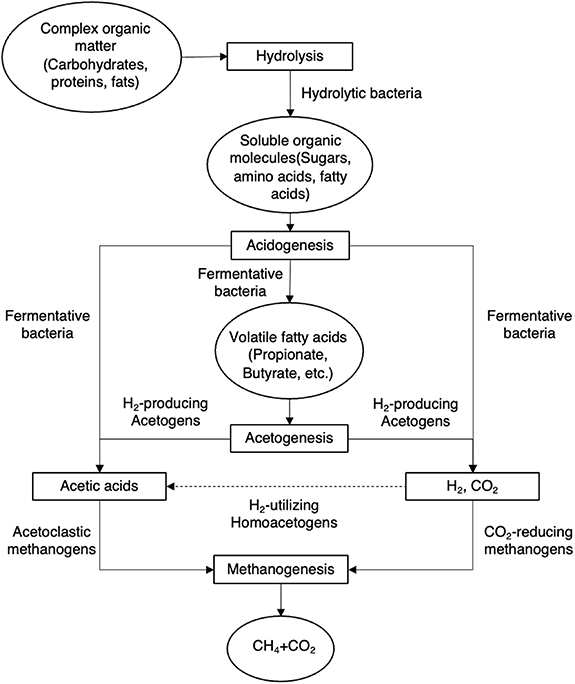

Figure 4 illustrates the four stages of AD: hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis (Adekunle and Okolie 2015). Hydrolysis initiates the breakdown of complex carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids into monomers such as simple sugars, glycerol, amino acids, and fatty acids. Microorganisms then convert these monomers into higher-value products (Liberti et al 2019). During acidogenesis, these monomers are further decomposed into hydrogen, carbon dioxide, ammonia, alcohols, and volatile fatty acids, including propionic, butyric, acetic, and lactic acid. In acetogenesis, acids and alcohols are transformed into hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and acetic acid. The final stage, methanogenesis, involves methanogenic bacteria breaking down acetic acid to produce methane and carbon dioxide. Additionally, methane can be produced via hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis, where hydrogen and carbon dioxide react in the presence of methanogens (Chandra et al 2012, Adekunle and Okolie 2015, Bajpai 2017). The product of the AD process is commonly known as biogas, which typically contains 50%–70% methane, 30%–50% carbon dioxide, and small amounts of other gases such as hydrogen sulfide, water vapor, and ammonia (Muzenda 2014).

Figure 4. Schematic of anaerobic digestion process.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageIn AD, the rate of microbial growth is a key factor. Operational parameters such as retention time, process temperature, pH, carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio, and organic loading rate (OLR) play critical roles in commercial AD plants. These parameters are carefully optimized to maximize microbial activity and, consequently, enhance the efficiency of the AD process (Van et al 2019).

During AD, bacteria metabolize organic materials to generate biogas. Only the organic biodegradable fraction of total solids (TS), referred to as volatile solids (VS), contributes to biogas production (Kumar et al 2006, Lee et al 2015, Liu et al 2021). VS typically constitute over 70% of the TS in suitable biowaste substrates, making them optimal for AD, while those with less than 60% are considered suboptimal (Vögeli 2014).

Table 1 presents VS/TS ratios and methane yields for various organic solid wastes. Pulp sludge exhibits an VS/TS ratio exceeding 80%, indicating its suitability for AD. However, the methane production yield from PPMS is comparatively low, making it commercially challenging to establish a biogas production plant. Inefficient biodegradation of organics leads to reduced biogas yields, which results in lower energy recovery and revenue.

Table 1. Comparison of VS content, methane potential, and biodegradability across organic feedstocks.

| Substrate | VS (% of TS) | Methane yield (ml/gVSadded) | VS removal/ COD removal/biodegradability | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary kraft pulp sludge | 83–86 | 190–240 | 25–40 | (Bayr and Rintala 2012) |

| Pulp and paper secondary sludge | 85 | 46.9 | 11.2 | (Do Carmo Precci Lopes et al 2018) |

| Pulp and paper primary sludge | 96.39 | 72.7 | 47–55 | (Bokhary et al 2022) |

| Energy grass | 81–89 | 221–360 | 62–73 | (Egwu 2021, Egwu et al 2022) |

| Food waste | 94–98 | 370.6–755.5 | 70–80 | (García-Depraect et al 2022, Luo and Pradhan 2024, Pongsopon et al 2023, Ren et al 2023) |

| Cattle manure | 56–66 | 247–387 | 61 | (Akamine et al 2023, Isabel et al 2022) |

| Organic fraction of municipal solid waste | 71–92 | 154–586 | 64 | (Abdoli and Ghasemzadeh 2024, Anaya-Reza et al 2024, Sailer et al 2021) |

| Fruit and vegetables | 94 | 360 | 79 | (Edwiges et al 2020) |

Aligning with established industry standards, considering a TS content of 12% and an OLR of 5 kgVS m−3d−1, the required digester volume for processing 500 tons of feed per day (a typical capacity for a kraft pulping plant) would be substantial and expensive. These high capital requirements, along with additional pretreatment and chemical costs, contribute to the low economic feasibility of biogas production in pulp and paper mills (Hosseini et al 2024a).

Later in this paper, we will examine the key factors contributing to low biogas yields and discuss potential strategies to overcome these challenges.

4. Challenges of PPMS digestion

4.1. High lignocellulosic content

High lignin content is considered one of the most significant drawbacks of fermenting lignocellulosic materials such as PPMS, as it makes lignocellulose resistant to chemical and biological digestion (Seidl and Goulart 2016). Due to the PPMS’s high lignocellulosic content and its intrinsic resistance to hydrolysis, this stage of the AD process is typically the bottleneck (Meyer and Edwards 2014). AD requires a longer sludge retention time to account for the slow microbial development. Longer retention times lead to larger reactors, which means more investment is necessary for industrial-scale implementation.

4.2. Nitrogen deficiency

To generate new cell mass, microorganisms require nitrogen, which they absorb in the form of ammonium. The optimum carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio for AD lies in the range of 20–30 (Veluchamy and Kalamdhad 2017). Previous work revealed that nitrogen deficiency is one of the other major concerns with the AD of PPMS (Puhakka et al 1992a, Bayr and Rintala 2012, Hagelqvist 2013, Meyer and Edwards 2014). A high C/N ratio, as observed in PPMS, results in the rapid consumption of nitrogen by methanogens, which negatively impacts microbial population growth, and slows digestion of available carbon (Verma 2002).

4.3. Low buffering capacity

The optimum pH for a generally stable AD process and high biogas yield lies in the 6.5–7.5. During digestion, hydrolysis and acidogenesis occur at acidic pH levels (pH 5.5–6.5), and methanogenesis is more efficient in the pH range of 6.5–8.2 (Mata-Alvarez et al 2014, Bhatt and Tao 2020). The buffering capacity of an anaerobic system must be always maintained, with an alkalinity level ranging from approximately 1000–5000 mg l−1 as CaCO3 (Waewsak et al 2010). Given the sensitivity of methanogens to acidic pH levels, it is crucial for the anaerobic treatment system to possess sufficient buffering capacity (alkalinity) to counteract pH changes. In a pulp and paper mill, the low nitrogen content of PS leads to a deficiency of ammonia required for microbial demands and a reduction in buffering ability, causing a decrease in pH. Therefore, pH adjustment must be considered when implementing the AD of PPMS. Low ammonia concentration was observed to lead to decreased acetoclastic methanogenic activity, biomass loss, and low methane outputs, attributed to inadequate buffering capacity and a lack of nutrient nitrogen (Puhakka et al 1992b, Procházka et al 2012).

5. Enhancing PPMS degradability for paper sludge valorization

The challenging and resistant nature of lignocellulose content, along with other undesirable characteristics in PPMS, poses a significant barrier to its bioconversion. Extensive efforts were directed toward exploring strategies and technologies to enhance the digestibility of sludge material and increase methane yield, consequently improving the biogas/methane production rate (Elliott and Mahmood 2007). Among these strategies, this review identifies emerging pretreatment technologies, co-digestion, sequential production of H2 and CH4 and biochar addition as more feasible to implement in PPI. More detailed description of the methods and how available resources in pulp and paper mills can be used to make these strategies practical in an AD-centered concept is provided in the following sections.

5.1. Pretreatment

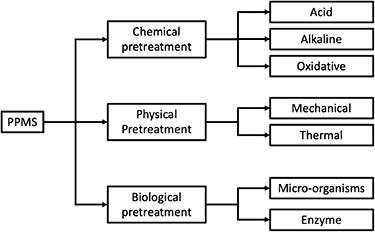

The invention and implementation of sludge pretreatment prior to AD to speed up the hydrolysis of sludge represent a relatively recent technological improvement that has the potential to make AD more viable (González-García et al 2011, Kim 2013, Deviatkin et al 2016, 2017, Sebastião et al 2016, Amiri and Karimi 2018, Poinot et al 2018, Guan et al 2024, Johnravindar et al 2025). Hydrolysable cellulose and hemicellulose in PPMS are generally protected from the enzymatic attack of anaerobic microorganisms by lignin, preventing the PPMS from being broken down into its monomeric, more metabolizable sugars (Veluchamy and Kalamdhad 2017). In order to make cellulose and hemicellulose accessible to enzymatic saccharification, pretreatment procedures are used to remove lignin, reduce cellulose crystallinity, enhance porosity, and increase surface area (Zhao et al 2012, Modenbach 2013, Wu et al 2017). Product recovery and purification in the subsequent processes (Hydrolysis, fermentation, and downstream processing) are all affected by the pretreatment outcome.

Various sludge pretreatment procedures have been explored to advance the AD technology of PPMS (figure 5). These procedures fall into three main categories: physical (Elliott and Mahmood 2007, Saha et al 2011, Bayr and Rintala 2012, Veluchamy and Kalamdhad 2017), chemical (Navia et al 2002, Lin et al 2009, Tyagi et al 2014) and biological pretreatment (Bayr et al 2013, Lin et al 2017, Yunqin et al 2010). The choice of the most suitable method depends on factors such as raw material characteristics, energy requirements, operational conditions, environmental impact, emission of inhibitory chemicals, and cost-effectiveness.

Figure 5. Different pretreatment methods of PPMS.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image5.1.1. Mechanical and thermal pretreatment

Mechanical pretreatments such as chipping, grinding, and milling are primarily employed to reduce particle size and disrupt the crystalline structure of cellulose. This increases the available surface area and improves enzymatic hydrolysis efficiency. However, these methods are typically energy-intensive and do not remove lignin, which limits their effectiveness when used alone (Zheng et al 2014, Veluchamy and Kalamdhad 2017). In a laboratory-scale study, Elliott and Mahmood (2012) evaluated three mechanical pretreatment technologies—mechanical shearing, sonication, and high-pressure homogenization—for their suitability in AD of pulp and paper mill activated sludge. Across all three treatments, the solids retention time (SRT) in the digesters was consistently reduced from 20 d to just 3 d. Remarkably, AD combined with high-pressure homogenization produced methane yields at a 3 d SRT comparable to those from a reference digester operated at 20 d. This finding highlights the potential of effective mechanical pretreatment to reduce digester volume requirements by up to sixfold, significantly improving system efficiency and scalability.

Thermal pretreatment is another effective strategy for enhancing the digestibility of lignocellulosic materials such as PPMS. By rapidly heating the material using hot air, steam, or liquid hot water, thermal pretreatment increases the accessible surface area of cellulose and improves its degradability by microbes and enzymes (Bayr et al 2013). This process typically involves subjecting the sludge to temperatures between 150 °C–200 °C and pressures ranging from up to 2500 kPa, promoting the hydrolysis of holocellulose through rapid decompression (Veluchamy and Kalamdhad 2017). Among the various thermal techniques, liquid hot water pretreatment stands out for its relatively low capital costs and minimal environmental impact, despite requiring a high-water input—approximately 2.63 gallons per kilogram of sugar produced (Tao et al 2013). It is considered one of the most environmentally friendly pretreatment methods due to its negligible global warming potential (GWP). In a study by (Bayr et al 2013), treatment at 150 °C for 10 min—either alone or in combination with other pretreatments—led to a 19%–31% increase in methane yields. This improvement was attributed to enhanced solubilization of chemical oxygen demand (COD), with soluble COD concentrations increasing more than ninefold following treatment. The resulting acceleration in methane production and higher yields suggest that biogas plants could potentially operate at significantly shorter hydraulic retention times (HRTs) than the typical 20–30 d required for untreated PPMS, offering meaningful techno-economic benefits.

5.1.2. Biological pretreatment

Biological pretreatment methods utilize microbial consortia or fungi—such as white-rot fungi or mushroom compost extracts—to degrade lignocellulosic structures under mild, sustainable conditions (Blanchette 1995). These methods are attractive for their sustainability, as they require no chemicals, operate at low energy inputs, and are generally cost-effective and simple to apply to materials like PPMS. However, biological pretreatment tends to be slow, requires significant space, and demands precise environmental control to maintain optimal microbial activity (Veluchamy and Kalamdhad 2017).

Lin et al (2017) investigated the use of the microbial consortium OEM1 for pretreating PPMS prior to AD. The treatment significantly enhanced lignin degradation and effectively reduced persistent pollutants such as adsorbable organic halides (AOXs). As a result, cumulative methane yield increased to 429.19 ml g−1 VS—1.4 times higher than the control. Moreover, the digestion process remained stable, with pH maintained between 6.1 and 7.5, and no signs of volatile fatty acid (VFA) inhibition. In a similar study, Yunqin et al (2010) used Pleurotus ostreatus compost extracts as a pretreatment, achieving a methane yield of 0.23 m3 CH4/kg VS—an increase of 134% compared to untreated sludge.

A study by Lin et al (2017) focused on the AD performance of PPMS pretreated with the microbial consortium OEM1. The AD performance of PPMS was improved after pretreating feedstocks with the active microbial consortium OEM1. During the pretreatment process, the active OEM1 exhibited a selectivity on the lignin deconstruction and highly efficiency on the persistent pollutant AOXs degradation. The cumulative methane yield reached 429.19 ml g−1 VS through this biological pretreatment, which was 1.4-fold compared to the control trial. Moreover, the AD system became more stable with an appropriate pH range (6.1–7.5) and without VFA inhibition after the active OEM1 pretreatment. Similarly, Yunqin et al (2010) used Pleurotus ostreatus compost extracts, leading to improved methane production (0.23 m3 CH4/kgVS), representing 134% of the untreated control.

However, the effectiveness of enzymatic pretreatments has shown mixed results. Bayr et al (2013) tested the commercial enzyme cocktail Accelerase 1500, which includes exoglucanase, endoglucanase, hemicellulase, and β-glucosidase. Although the treatment led to notable increases in soluble COD and VFA concentrations, the improvement in methane yield was limited. Similarly, Karlsson et al (2011) found no significant enhancement in methane production when using a blend of cellulases, proteases, and lipases to pretreat kraft SS. The authors attributed this to the high viscosity of the reaction mixture, which likely hindered enzyme-substrate interactions by limiting access to binding sites.

5.1.3. Alkali pretreatment

Among various pretreatment strategies, alkaline pretreatment is widely recognized for enhancing the biodegradability of complex lignocellulosic materials (Navia et al 2002, Lin et al 2009). This method, typically employing sodium or potassium hydroxide, disrupts lignin structures and increases cell wall permeability, thereby improving microbial and enzymatic access to cellulose (Loow et al 2016). Advantages of alkaline pretreatment include low operational costs, minimal holocellulose degradation, and reduced formation of fermentation inhibitors (Cheng et al 2010). However, high reagent consumption remains a key drawback, highlighting the ongoing need for more cost-effective alkaline reagents (Loow et al 2016).

Wood et al (2010) compared thermal, caustic (alkaline), and sonication pretreatments for enhancing AD of SS from pulp and paper mills. All methods improved biogas yields, with thermal pretreatment being the most effective, followed closely by caustic, and then sonication.

Combining chemical and physical methods often yields synergistic benefits. Tyagi et al (2014) investigated alkali-assisted microwave (MW, 50 °C–175 °C) and ultrasonic (US, 0.75 W ml−1 15–60 min) pretreatments on waste-activated sludge from pulp and paper mills. While MW alone resulted in 33% COD and 39% volatile suspended solids (VSS) solubilization, the addition of alkali (pH 12) boosted solubilization to 78% and 66%, respectively. Similarly, US pretreatment alone achieved 58% COD and 37% VSS solubilization, which increased to 66% and 49% with alkali addition. Biogas yield improved by 47% compared to the control and by 20% over US-alone treatment for the US-alkali combination. However, in the case of MW-alkali treatment, methane production was only 6.3% higher than the control and 8.3% lower than MW alone—likely due to microbial inhibition under extreme conditions.

Thermochemical pretreatments that combine heat and alkali showed particularly strong results (Wood et al 2010). Fioreze et al (2022) evaluated thermal, thermal-alkaline, and mechanical methods for enhancing AD of waste-activated sludge. Thermal-alkaline pretreatment led to over a 7-fold increase in soluble COD and a 4-fold increase in biochemical oxygen demand. The theoretical biochemical methane potential improved from 211 mL CH4/g VS (raw sludge) to 373–378 mL CH4/g VS post-treatment. This approach offered the best performance across all metrics while requiring lower temperatures and retention times compared to thermal treatment alone.

Another promising approach is electrohydrolysis, which combines electrical and chemical (alkali) pretreatment. This process involves passing a direct current through an ionic medium, facilitating solubilization and delignification by breaking polymeric bonds (Zheng et al 2014). Electrohydrolysis enhances biogas production by increasing organic matter liquefaction while reducing the need for high chemical doses or energy inputs, making it a cost-effective and energy-efficient option. Veluchamy et al (2018) conducted a biochemical methane potential (BMP) assay to evaluate the effects of electrohydrolysis on lignocellulosic waste. Methane yield increased by 13.8%, reaching 301 ± 3 ml CH4/g VS. Additionally, a net energy gain of 13 224 kJ was achieved—1.51 times higher than that of conventional thermal pretreatment—demonstrating the strong potential of electrohydrolysis as an energy-positive and scalable strategy for enhancing AD.

5.1.3.1. GLD as an alkaline pretreatment agent

The pretreatment process constitutes a significant portion, up to 40%, of the processing cost for producing biofuels and value-added products from lignocellulosic materials (Kucharska et al 2018). Therefore, it is imperative to explore cost-effective alternatives to the expensive chemicals currently used in lignocellulosic biomass pretreatment. Investigating the application of GLD in alternative processes, such as lignocellulosic pretreatment, can address disposal concerns and enhance the value of waste materials.

The alkaline waste product from the kraft pulping industry, GLD, has gained attention recently. Various alkaline species in GLD waste, including Na2S and Na2CO3, make it suitable for alkaline pretreatment, and the presence of CaCO3 provides exceptional buffering properties (Chen et al 2015). Moreover, GLD’s mixed alkalic salt action suggests an improved and more efficient pretreatment strategy compared to NaOH, which targets specific bonds like the ester bonds between ferulic acid and hemicellulose (Modenbach 2013). The Na2CO3 component in GLD cleaves cell wall matrix ester and glycosidic linkages, resulting in structural changes in lignin, cellular swelling, and partial de-crystallization (Cheng et al 2010). Additionally, the HS species of Na2S facilitate a strong nucleophilic assault, breaking phenolic-aryl ether linkages of lignin and allowing the removal of lignin moieties with only a mild impact on carbohydrates (Gu et al 2013).

Though GL is most famous for its role in the kraft pulping process, it was also used in lignocellulosic pretreatment (Wu et al 2012, Gu et al 2013). GLD waste, chemically identical GL, provides cost-effective pretreatment benefits like high delignification and no fermentation inhibitors under milder conditions. Since it is a byproduct of kraft pulping, using GLD in treatment methods can save money on waste management for the PPI. GLD, with a pH over 10, can replace expensive catalysts like NaOH (pH 13), and its alkaline nature eliminates the need for high-priced materials or complex reactor designs to handle severe reaction conditions and corrosion (David et al 2020, Sewsynker-Sukai et al 2020).

David et al (2020) investigated and optimized GLD as a novel pretreatment method to enhance bioethanol production from corn cobs. The study aimed to design an efficient GLD pretreatment regime to increase glucose yields and ethanol production from cost-effective lignocellulosic wastes like corn cobs, while reducing energy input and bioprocess costs. The findings suggest that GLD pretreatment can perform comparably to potent alkaline catalysts such as NaOH. In another study by David et al (2021), two innovative kraft waste-based pretreatments were optimized for corn cobs. The methods involved microwave-assisted combinations of GLD and paper wastewater, as well as steam-assisted combinations of GLD and paper wastewater. Rorke et al (2021) optimized a surfactant-assisted GLD pretreatment for enhancing the digestibility of paper mill sludge. The study demonstrated a reduction in sugar content by 16.38 g l−1 (0.328 g g−1) under optimal pretreatment conditions. Hydrogen yields of 2.73 ml g−1 in separate hydrolysis and fermentation (SHF) and 3.72 ml g−1 in simultaneous saccharification and fermentation further demonstrated the efficacy of the pretreatment approach. These results suggest that GLD pretreatment could offer significant cost and energy savings for the PPI.

5.2. Co-digestion of PPMS with the industrial wastes

AD of single substrates has various limitations associated with substrate characteristics; most of these issues can be resolved by the addition of a co-substrate. Synergistic effects are attributed to elements that are naturally linked to the qualities and composition of co-substrates. Increased microbial diversity, diluted toxic compounds, enhanced buffering capacity, improved nutrient balance and safe and better quality digestate are all potential benefits (Bolzonella et al 2006, Mata-Alvarez et al 2014, Ebner et al 2016, Xie et al 2018).

5.2.1. Rejected fibers (RFs) as a possible source for co-digestion with sludge

Nowadays, different sorts of waste mixtures are explored and used. A primary factor in deciding which co-substrate to use is how much it will cost to transport it from the place of generation to the AD facility. Therefore, to reduce the transportation cost, paper sludge could be mixed with other waste streams generated in the pulp and paper mill. RF, originating from pulp mills, is a viable co-substrate for AD. While conventionally mixed with black liquor and recycled in the process, RF poses economic potential beyond its current applications. Physically and mechanically RF is close to the exported pulp (Aguayo et al 2018). The high cellulose concentration in RF suggests its potential use as a co-substrate to enhance methane generation from PPMS (Bajpai 2015a).

Few details are available in the literature about RF valorization, despite the high demand for solutions to either reduce RF production or modify its positive features for manufacturing biofuels and value-added products. In order to clarify the synergistic effect, Xie et al (2017) presented anaerobic mono-digestion and co-digestion of primary sewage sludge with two organic wastes (food waste and paper pulp reject). The study revealed that due to its predominantly powdered cellulose nature, paper pulp reject had the lowest hydrolysis rate (kh = 0.18 d−1). However, co-digestion of RF and PS enhanced hydrolysis kinetics, resulting in increased specific methane yields (SMY). This research highlighted the potential of transforming the diverse and abundant waste from pulp and paper mills into valuable resources using conventional and integrated biorefinery technologies.

5.2.2. Co-digestion of PS and SS

For AD, PS is generally preferred over SS due to its more favorable chemical composition. PS contains lower lignin content, which reduces its resistance to hydrolysis—the rate-limiting step in AD—thereby requiring shorter retention times for effective bioconversion. However, as previously noted, the AD process is often constrained by the nutrient deficiency of PS, which limits microbial activity and overall process efficiency.

Nutrient deficiency in PPMS could be compensated by mixing PS and SS in a particular ratio. Primary and SS characteristics vary according to the different wastewater treatment processes. SS has a higher concentration of nutrients than PS. The higher nitrogen value of SS is due to the addition of nitrogen in biological treatment because nutrient levels are already low in wastewater from pulp and paper mills. Therefore, with the addition of SS to the PS with the correct ratio, these two substrates can cover up each other’s process deficiencies and improve the overall methane yield.

To the best of the author’s knowledge, only one study (Bayr and Rintala 2012) compared the mono-digestion of PS with the co-digestion of PS and SS. However, this study found no improvement in methane yield. The investigation focused on a single mixing ratio (3:2) of primary and SS, and the reasons for this observation were not clearly explained. Consequently, more research is required to explore various ratios of mixing PS and SS to identify an optimal blend and investigate the potential synergistic effects between these two substrates.

5.2.3. Co-digestion with nitrogen-rich feedstocks

As previously mentioned, nitrogen deficiency (high C/N ratio) is a major limitation in the AD of PPMS. The rapid uptake of available nitrogen by methanogens can inhibit the overall AD process and slow down organic matter degradation. To address this issue, co-digestion with nitrogen-rich organic wastes is often employed to balance the C/N ratio. This strategy enhances the system’s buffering capacity, improves nutrient availability, and supports a more stable and efficient methanogenic phase (Lin et al 2012, Parameswaran and Rittmann 2012).

Currently, common nitrogen-rich substrates for co-digestion with PPMS includes food waste and animal manure (Lin et al 2011, 2012, 2013, Parameswaran and Rittmann 2012, Chen et al 2013, Li et al 2020). Food waste is highly attractive for AD due to its significant methane potential (zhang et al 2007, Yirong et al 2013). Li et al (2010) noted that food waste contains approximately 23% fat, which, under specific conditions, can significantly enhance methane production from lipid-rich waste such as fats and oils (Wan et al 2011, Zhang et al 2013). However, long-chain fatty acids formed during fat and lipid degradation can be inhibitory at concentrations over 1.0 g l−1 (Appels et al 2008) and toxic to both syntrophic acetogens and methanogens (Hanaki et al 1981), limiting nutrient transport to cells by adsorbing onto microbial surfaces (Pereira et al 2005). Thus, treating only food waste through AD is challenging (Zhang et al 2013).

On the other hand, animal manure, particularly pig waste (PW), poses unique challenges due to its high organic nitrogen content, which is converted to ammonia during SHF (Callaghan et al 2002). This can suppress AD due to the low C/N ratio of animal manure.

Table 2 shows the works on anaerobic co-digestion systems of PPMS with food waste and animal manure. The reviewed studies demonstrate significant improvements in methane production and process stability. Combining PW with PPMS in various ratios revealed that a 3:1 (v/v) PW:PS ratio yielded the highest methane production efficiency while reducing methane production lag times (Parameswaran and Rittmann 2012). Similarly, co-digestion of PPMS with FW in a 1:1 mass ratio resulted in the highest methane yields, COD removal efficiencies, and process stability, with no toxicity observed (Lin et al 2012), findings confirmed in subsequent studies (Lin et al 2013a). Additionally, co-digestion of PPMS with monosodium glutamate waste liquor and pig manure under mesophilic and thermophilic conditions, respectively, also showed high methane yields and stable processes without requiring pH adjustments (Lin et al 2011, Chen et al 2013). These findings underscore the potential of co-digestion strategies in optimizing methane production from mixed organic waste streams.

Table 2. Anaerobic co-digestion systems of PPMS with food waste and animal manure.

| Substrate | Mixing ratio | Tempreture | Reactor | HRT (day) | Methane yield (mlCH4/g-VSadded) | Organics removal | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPMS: Pig manure | 1:1 | Thermophilic | Stirred semi-continuously | 10 | 71.58 ± 8.75 | 55.74 ± 0.27% VS removal | (Chen et al 2013) |

| PPMS: Food waste | 1:1 | Mesophilic–thermophilic | Batch | 30 | 432.3 | 86% SCOD removal | (Lin et al 2013a) |

| PPMS: Pig waste | 1:3 | Mesophilic | Semi-continuous | 80 | — | 49% TCOD removal | (Parameswaran and Rittmann 2012) |

| PPMS: Food waste | 1:1 | Mesophilic | Batch | 55 | 256 | 93.9% SCOD removal | (Lin et al 2012) |

| PPMS: monosodium glutamate waste liquor | — | Mesophilic | Batch | 35 | 200 | 52% VS removal | (Lin et al 2011) |

HRT: Hydraulic Retention Time; VS: Volatile Solids; SCOD: Soluble Chemical Oxygen Demand; TCOD: Total Chemical Oxygen Demand.

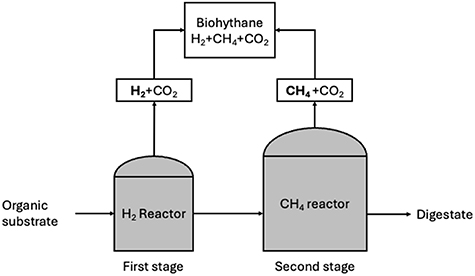

5.3. Two-stage AD

In conventional AD applications, acid-forming and methane-forming bacteria coexist within the same reactor. However, due to significant differences in their physiological characteristics, nutritional requirements, growth kinetics, and susceptibility to external conditions, their interaction is inherently unstable (Pohland and Ghosh 1971). This instability in traditional AD reactor designs led to the exploration of alternative approaches to enhance process efficiency. One such approach involves the physical separation of acidogenic and methanogenic stages, enabling optimal conditions for each microbial group (Demirel and Yenigün 2002, Nasr et al 2012).

In a two-stage process, the first three stages (Hydrolysis, acidogenesis, and acetogenesis) are performed in one digester, and the final step (methanogenesis) is performed in a different digester (figure 6). Complex organic polymers are broken down into simpler molecules by hydrolytic bacteria in the first reactor (stage), which are then fermented by acidogens into hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and organic acids. Finally, all the organic acids are fermented by acetogens into acetic acid, H2, and carbon dioxide. Methanogens convert the byproducts of the first stage into methane and carbon dioxide in a second digester (Roy and Das 2016). This method provides excellent stability to the diverse groups of microorganisms and better process control. This process improves the CH4 yield and energy content in addition to enhancing the first stage of H2 generation and collection (Wang et al 2022). The utilization of a two-stage H2–CH4 (Collectively referred to as biohythane) process showed significantly improved hydrolysis and higher energy outputs compared to a single-stage methanogenic process, making it an attractive alternative for increasing the CH4 content of the biogas produced (Kyazze et al 2007).

Figure 6. Schematic of two stage H2–CH4 production process.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTwo-stage AD has many advantages over one-stage AD, including higher energy recovery, higher COD removal, higher H2 and CH4 yields, shorter HRT and a lower carbon dioxide (CO2) in biogas concentration (Massanet-Nicolau et al 2013, Hans and Kumar 2019). When created at the same time, H2 and CH4 could cancel out each other’s drawbacks and maximize their benefits. Due to their synergistic qualities, the two-stage AD process that involves co-production of H2 and CH4 as biohythane is gaining popularity. In comparison to compressed natural gas, biohythane is an advantageous transportation fuel due to its many advantages, such as its high flammability range, shorter ignition time and lower ignition temperature, absence of nitrous oxide (NOx) emissions, and enhanced engine performance that requires no special configuration (Bauer 2001, Gaffney and Marley 2009, Hans and Kumar 2019).

In an effort to anaerobically digest lignocellulosic substrate, the overall energy yield rose by 38% when a two-stage hydrogen-biogas system was used instead of a single-stage biogas reactor (Massanet-Nicolau et al 2013). The highest hydrogen yield of 64.48 ml g−1 VSfed and the highest methane yield of 432.3 ml g−1 VSfed were obtained in research on mesophilic anaerobic bioethanol synthesis from PPMS and FW using a two-stage H2 and CH4 process by Lin et al (2013). There was no accumulation of volatile fatty acids in the reactor during the hydrogen-methane fermentation, and neither NH3–N nor Na+ inhibited the process. Rates of soluble COD removal between 71% and 87% were attained. This research shows that the two-stage mesophilic, thermophilic process of anaerobic co-digestion of PPMS and FW for hydrogen-methane co-production is a stable, dependable, and successful method for energy recovery and bio-solid waste stabilization.

While two-stage AD systems offer more process stability and adaptability, implementing two-stage AD systems in the commercial sector faces challenges due to the trade-off between increased methane yield and the higher capital expenditure (Chu et al 2008). The current lack of economic feasibility and limited knowledge pose challenges to the commercial implementation and operation of the process. Additionally, the choice of feedstock determines the digester design (Rajendran et al 2020), making it crucial to reduce energy requirements through proper operation. Further research is needed to address uncertainties surrounding the reactor configuration for PPMS treatment.

5.4. Digestate management and nutrient recovery

The AD process generates biogas, which can be used for energy recovery, while producing digestate as a residual waste stream. Digestate is a high-moisture organics/inorganics matrix rich in nutrients and contaminants. Typically, digestate undergoes solid–liquid (S/L) separation, yielding solid digestate and liquid digestate fractions. This cost-effective separation reduces digestate volume, lowers transportation expenses, enhances process efficiency, and eases storage requirements (Plana and Noche 2016, El-Fatah Abomohra et al 2021, Wang et al 2023).

Agricultural valorization of digestate, including its use as fertilizer, soil amendment, and growing medium, is considered the most direct and economically viable route. Digestate’s suitability for soil amendment stems from its high concentrations of essential nutrients, notably nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K). However, digestate composition significantly varies with the type of feedstock, causing inconsistencies in the quality of the resulting fertilizer. The application of PPMS-derived digestate to land can also present environmental risks due to the potential presence of heavy metals. Although heavy metal concentrations in PPMS are generally low (Turner et al 2022), studies reported that land application of biosludge occasionally exceeds permissible metal concentrations in soils (Rashid et al 2006).

Despite these challenges, internal management of PPMS-derived digestate within pulp and paper mills can significantly mitigate environmental risks and operational costs. AD within pulp and paper mills effectively releases valuable nutrients—primarily nitrogen and phosphorus—that can be re-utilized, enhancing the sustainability of wastewater treatment processes (Meyer and Edwards 2014). Recycling nitrogen and phosphorus from AD back into the production process reduces the necessity for external nutrient supplements, resulting in cost savings and a more sustainable waste treatment approach. Maximizing revenue through the valorization of PPMS necessitates identifying sustainable approaches to handle and recycle this nutrient-rich pulp and paper sludge digestate. This not only facilitates closing the resource loop but also fosters a circular economy.

Elliott and Mahmood (2012) highlighted that AD of SS generates excess nutrients, which, when released back into the wastewater stream, can fulfill the mill’s nutrient needs. Their study on AD of SS found that, if the process is optimized and nutrients are recovered from the resulting digestate, it could provide 36%–54% of the nitrogen and 19%–24% of the phosphorus required for wastewater treatment in a paper mill. Consequently, controlled nutrient recycling from SS digestate represents a cost-effective, sustainable approach, minimizing chemical inputs and associated operational expenses, thereby advancing circular economy goals within the PPI.

5.5. Biochar addition

Biochar has gained significant attention for its role in biogas upgrading, enhancing system stability, and accelerating the degradation of refractory substances. Economic and environmental analyses demonstrated that incorporating biochar is both cost-effective and environmentally sustainable for improving AD efficiency (Zhao et al 2021). Biochar, a carbon-rich solid product, is thermochemically generated from waste biomass such as PPMS. During the pyrolysis process, which occurs at temperatures between 350 and 650 °C, biomass can be effectively converted into valuable products like biochar, syngas, and bio-oil (Chi et al 2021). This process involves three main reactions: first, the evaporation of free water; second, the decomposition of unstable polymers; and finally, the destruction of refractory substances and the release of volatiles (White et al 2011, Zhao et al 2021).

Adding biochar to AD systems can mitigate toxin inhibition, shorten the methanogenic lag phase, immobilize functional microbes, and enhance electron transfer between methanogenic and acetogenic microbes (Pan et al 2019, Chiappero et al 2020). Biochar’s strong buffering capacity, due to its abundant acidic/alkaline functional groups and metal ions, helps resist the acidic/alkaline shocks often encountered in AD systems (Zhao et al 2021). Studies showed that biochar addition can reduce lag time by 28%–64% and increase biogas production by 22%–40% (Wang et al 2018). Additionally, it enriched the relative abundance of electroactive microorganisms and methanogens by 24.61% and 43.8%, respectively (Wang et al 2018).

Recent studies emphasize the environmental advantages of producing biochar from PPMS or digestate resulting from AD of PPMS. In the study conducted by Mohammadi et al (2019a) life cycle assessment (LCA) is employed to compare traditional incineration with AD, followed by either incineration or pyrolysis of the digestate. The findings indicated that pyrolysis for biochar production significantly reduces environmental impacts, especially aquatic ecotoxicity, making it the preferred method. A subsequent study by the same group (Mohammadi et al 2019b) evaluated incineration, pyrolysis, and hydrothermal carbonization of biosludge using LCA. All three methods showed improved environmental performance relative to landfilling. Among them, pyrolysis yielded the lowest eutrophication and ecotoxicity impacts, while HTC exhibited the lowest acidification potential. In addition, Simões Dos Reis et al (2022), optimized the biochar production process from PPMS using a Box–Behnken experimental design, identifying optimal conditions for maximizing surface area and pore structure. The resulting biochar demonstrated high adsorption capacities for emerging pollutants such as diclofenac and amoxicillin, highlighting its potential for reuse in pollutant removal applications. Collectively, these findings emphasize the environmental superiority and functional potential of biochar production from PPMS.

5.6. Process optimization

Understanding the complex AD process for PPMS is essential for refining operational conditions, adjusting process parameters, managing intra- and inter-phase interactions, and identifying rate-limiting factors throughout the production cycle. Such detailed insights enable effective optimization of the PPMS AD process (Roopnarain et al 2021).

Modeling is a critical tool for optimizing AD operations, offering the potential to significantly reduce investment costs, energy consumption, and environmental impacts. However, a major barrier to adopting AD technology within the pulp and paper industry is the lack of tailored AD models for paper mill effluent. Existing models inadequately simulate the distinct characteristics and reaction pathways specific to this feedstock. For example, the widely utilized AD model No. 1 (ADM1) primarily targets sewage sludge and does not account for the unique properties of paper mill sludge (Batstone et al 2002).

AD models are generally classified as mechanistic and empirical (Rocha-Meneses et al 2022). The following section provides a review of both approaches, highlighting their defining features and evaluating their applicability and adaptation to the anaerobic treatment of PPMS as reported in the literature.

5.6.1. Mechanistic models

Mechanistic models, also known as first-principles or white-box models, are mathematical representations based on fundamental physical laws. These models explain phenomena through physical or chemical causes and require an in-depth understanding of chemical kinetics, heat and mass transfer, momentum transfer, materials composition, boundary conditions, thermodynamics, and system properties. Although they exhibit less bias, they often have higher variance due to parameter uncertainties and estimation needs (Sansana et al 2021).

The ADM1, developed by Batstone et al (2002), is widely used for AD simulations. ADM1 covers substrate breakdown and the four main stages of AD, employing first-order kinetics for extracellular processes and Monod kinetics for intracellular reactions. The model includes 19 equations for biochemical rates, three for gas-liquid transfer, and six for acid-base kinetics, providing comprehensive kinetic rate equations and stoichiometry matrices.

Rajendran et al (2014) developed a process simulation model based on ADM1 and implemented in Aspen Plus® for PPMS. This model, calibrated for kraft pulp mill sludge, showed cumulative methane production of 46.9 NmL CH4/gVS in 30 d and effectively simulated methane yield from bleached kraft pulp mill SS with minor adjustments. Huang et al (2021) created a simulation model to assess a full-scale anaerobic biochemical system for deinking pulp (DIP) wastewater treatment. Modified from ADM1, this model considered the system’s hydrodynamics and influent DIP wastewater characteristics. Using the Monte Carlo technique, it identified and optimized sensitive parameters affecting effluent COD and biogas production. The model, calibrated with 150 d of data and validated with 100 additional days, showed good agreement with simulation results, offering practical guidance for full-scale anaerobic wastewater treatment.

5.6.2. Data-driven models

In contrast, data-driven, black-box, statistical, or empirical models do not demand extensive prior knowledge about the system. Instead, they heavily lean on available data collected from the process, requiring sufficient quantity and quality of information for proper estimation. From a statistical perspective, data-driven models typically exhibit more bias because of the extensive simplifications and assumptions made (Sansana et al 2021). Moreover, the datasets and resulting models are based on current conditions, so, using such models for forecasting becomes problematic when conditions change, such as using new substrates or altering their loading rate. There are doubts regarding the efficacy of machine learning (ML) in chemical engineering due to concerns over the black-box nature of ML models, limiting their extrapolation abilities, interpretability, and prediction uncertainties that may deviate from physical constraints (Sansana et al 2021).

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) is a data-driven method employed in biogas modeling and optimization (Levstek and Lakota 2010, Sansana et al 2021). This black box model lacks specific knowledge about the underlying biological processes, relying solely on the quality and accuracy of the input datasets used for calibration or training. ANN, an artificial intelligence technique, emulates the human brain to forecast both linear and non-linear processes across different operational layers.

In a study by Sonwai et al (2023), ML was utilized to predict SMY using a dataset comprising 14 features related to lignocellulosic biomass characteristics and operating conditions of completely mixed reactors under continuous feeding. The random forest (RF) model proved to be the most effective, achieving a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.85 and a root mean square error of 0.06. Biomass compositions had a significant impact on SMY, with cellulose being the most critical factor over lignin and biomass ratio. Experimental results confirmed the RF model’s influential factors, achieving the highest SMY at 79.2% of the predicted value. This study demonstrated the successful application of ML for AD modeling and optimization.

6. Techno-economic analysis (TEA) and LCA

6.1. TEA of AD using PPMS

As discussed by Murthy (2022) and Rajendran and Murthy (2019), The TEA helps identify potential technical and economic bottlenecks, providing critical insights into the viability of bioenergy and bio-based product projects. The AD process can be categorized into three key stages: (i) feedstock production, collection, and transportation, (ii) pretreatment, digestion, and byproduct management, and (iii) post-processing and biogas utilization (Rajendran and Murthy 2019).

Feedstock collection and transportation typically rely on trucks, trailers, or manual methods. According to the World Bank (Bhada-Tata and Hoornweg 2012), waste management entities allocate 20%–50% of their budgets to these services. In the United States, the average municipal solid waste landfill tipping fee is $58.47 per ton. However, integrating AD directly within pulp and paper mills can mitigate or eliminate these costs by reducing external transportation requirements.

Before digestion, substrates may undergo pretreatment using various technologies or proceed directly to AD. After digestion, the liquid stream, enriched with nutrients, is typically dewatered and either disposed of in landfills or repurposed. The biogas stream, primarily methane, undergoes purification before its final application (Rajendran et al 2014).

The final stage of the TEA evaluates the costs associated with biogas purification for various applications. Biogas can be used in combined heat and power (CHP) systems, converted to electricity via combustion engines, fuel cells, or gas turbines, or upgraded for vehicle fuel. The generated electricity can be utilized on-site or supplied to the electric grid (Kabeyi and Olanrewaju 2022). Several biogas upgrading technologies exist, including water scrubbing, amine absorption, pressure swing adsorption, membrane separation, organic solvent scrubbing, and cryogenic separation. Among these, water scrubbing accounts for 34% of implementations, while chemical scrubbing and membrane separation each constitute 21% (Sun et al 2015, Kapoor et al 2019, Lombardi and Francini 2020).

Several studies assessed the economic viability of AD configurations using kraft PPMS, as summarized in table 3. Hosseini et al (2024b) conducted a comprehensive TEA of three PPMS AD scenarios—base case, alkaline pretreatment, and co-digestion with food waste—under two biogas utilization pathways: CHP and biomethane production. Among these, the co-digestion scenario demonstrated the highest net present value (NPV) of $7.57 million and a return on investment (ROI) of 13.95%, highlighting its economic potential. Sensitivity analysis identified food waste TS input flowrate, carbohydrate degradation efficiency, tipping fee, and labor cost as key influencing factors, based on minimum selling price (MSP) of biomethane. Doddapaneni and Kikas (2023) investigated the integration of torrefaction with AD to valorize 60 000 tonnes/year of wet kraft sludge. Although the approach enabled multi-product generation—including torrefied pellets, VFA, and biomethane—the integrated system resulted in a negative NPV. The minimum selling price of torrefied pellets was notably higher than that from standalone torrefaction systems. However, the study noted that biomethane and VFA prices could be reduced by 90% and 64%, respectively, if the torrefied pellet price reached 260 €/t. Sludge moisture content was identified as the most sensitive parameter affecting profitability.

Table 3. Summary of techno-economic analyses on anaerobic digestion of kraft pulp and paper sludge.

| Feedstock | Process configuration | Products | Plant capacity | Techno-economic insights | Sensitive parameters | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kraft PPMS |

| Biomethane, CHP | 500 t/day PPMS (3% TS) | Co-digestion scenario yielded highest NPV ($7.57 M) and ROI (13.95%). Other scenarios were not financially viable. | Based on biomethane MSP: FW TS input flowrate, carbohydrate degradation rate, tipping fee, labor cost. | (Hosseini et al 2024b) |

| Kraft Pulp Sludge |

| LBG | PS: 1.3 t TS/day SS: 9.0 t TS/day | Production potential: 26–27 GWh/year; LBG production cost: €0.47–0.82/L diesel equivalent; DPP: 7.8 years | Based on production cost: Investment cost, LBG yield, Depreciation time | (Larsson et al 2015) |

| Kraft Pulp Sludge | Torrefaction integrated with AD | Biomethane, VFA, Torrefied pellets | 60 000 t/year wet sludge | MSP of pellets in integrated approaches was higher than standalone pulp sludge torrefaction Negative NPV for integrated approaches Biomethane and VFA prices could be reduced by 90% and 64% respectively at torrefied pellets selling price of 260 €/t. | Based on NPV: Sludge moisture content | (Doddapaneni and Kikas 2023) |

WWT: wastewater treatment; CHP: combined heat and power; LBG: liquid biogas; NPV: net present value; ROI: return on investment; DPP: discounted payback period; MSP: minimum selling price.

Larsson et al (2015) investigated AD integration with liquid biogas production in Nordic kraft pulp mills, identifying significant biogas production potential and economic benefits, particularly for renewable vehicle fuel. However, the study highlighted challenges in achieving profitability due to extended payback periods. Alternative strategies, such as producing compressed biogas or expanding wastewater treatment capacity, could improve economic viability.

Overall, these studies highlight the economic potential of AD and integrated processes in the PPI. By addressing economic challenges and optimizing system configurations, these approaches can advance both sustainability and financial viability in waste management and resource utilization.

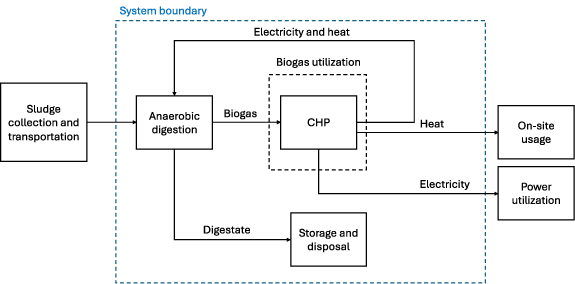

6.2. LCA of AD using PPMS

In the LCA of the AD-CHP process utilizing PPMS, the system boundary includes biogas production in the AD plant, electricity and heat generation in the CHP plant, and digestate management (figure 7). While a portion of the generated heat and electricity is used within the AD plant, excess electricity is exported to the national grid, and heat is utilized on-site. The boundary may also extend to encompass sludge collection and transportation.

Figure 7. System boundary for AD-CHP system.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageLCA has been widely applied to sludge management practices in general (Deviatkin et al 2016, 2017, Sebastião et al 2016, Poinot et al 2018). However, a review of the literature indicates that the environmental impacts of utilizing PPMS in AD technologies remain underexplored. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, only Mohammadi et al (2019) specifically investigated this aspect. This study assessed the environmental impacts of processing 1 tonne of dry matter pulp and paper mill biosludge for biogas, heat energy, and biochar production. The evaluated thermochemical treatment pathways included: (i) a combination of AD and incineration and (ii) a combination of AD and pyrolysis. The system boundary encompassed all processes from biosludge collection and pre-processing (e.g. dewatering) to bioenergy and soil amendment generation. The results demonstrated substantial reductions in climate change impacts—145% for the AD-incineration pathway and 391% for the AD-pyrolysis pathway—compared to conventional incineration. These reductions were largely attributed to the substitution of fossil-based energy sources with biomethane and recovered heat, as well as carbon stabilization in soil through biochar application. Supporting these findings, Møller et al (2009) conducted an LCA of a generic AD facility, estimating the GWP of biogas utilization for electricity or vehicle fuel, with digestate used as fertilizer. Reported GWP values ranged from—95 to—4 kg CO2-eq per tonne of wet waste, depending on the displaced energy source. The GWP of—17 kg CO2-eq per tonne of wet biosludge reported by Mohammadi et al (2019) for the AD–pyrolysis pathway falls within this range, aligning with previous findings on the environmental benefits of AD. Overall, this study highlights that biogas generation from paper mill biosludge, when coupled with heat recovery or biochar production, presents a more environmentally sustainable alternative to conventional incineration for sludge management.

7. Conclusion

This review highlights both the opportunities and challenges associated with integrating AD into pulp and paper mill operations. AD offers a sustainable pathway for converting PPMS into valuable bioproducts. However, several key challenges—such as high lignin content, nitrogen deficiency, low buffering capacity, and high capital costs—continue to hinder full-scale adoption.

Promising strategies to enhance methane yield and process stability include co-digestion, biochar addition, two-stage hydrogen/methane (H2/CH4) production, and various pretreatment methods. Additionally, resource recovery through digestate valorization and on-site nutrient recycling can significantly reduce operating costs and environmental impacts.

Nevertheless, these approaches require further optimization and economic validation. The application of advanced modeling tools, along with TEA and LCA, is essential for bridging the gap between research and practical implementation.

Data availability statement

All data that support the findings of this study are included within the article (and any supplementary information files).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Credit author statement

Erfan Hosseini: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft, Visualization.

Selen Cremaschi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Zhihua Jiang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.