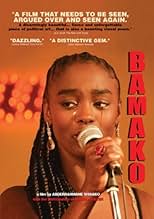

Bamako

- 2006

- Tous publics

- 1h 55m

Bamako. Melé is a bar singer, her husband Chaka is out of work and the couple is on the verge of breaking up... In the courtyard of the house they share with other families, a trial court ha... Read allBamako. Melé is a bar singer, her husband Chaka is out of work and the couple is on the verge of breaking up... In the courtyard of the house they share with other families, a trial court has been set up. African civil society spokesmen have taken proceedings against the World Ba... Read allBamako. Melé is a bar singer, her husband Chaka is out of work and the couple is on the verge of breaking up... In the courtyard of the house they share with other families, a trial court has been set up. African civil society spokesmen have taken proceedings against the World Bank and the IMF whom they blame for Africa's woes... Amidst the pleas and the testimonies, ... Read all

- Director

- Writer

- Stars

- Awards

- 4 wins & 2 nominations total

- Saramba

- (as Hélène Diarra)

- Avocat de la défense

- (as Mamadou Konaté)

- Le procureur

- (as Magma Gabriel Konaté)

- Cow-boy

- (as Dramane Sissako)

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

The title: 'Bamako', is loud and proclaimed. The word is a proper noun it is the capital city of Mali, an African country, and that is the tone for the film focusing on a courtroom based discussion regarding the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, a corporation set up to help fund developing or underfunded nations. The topic is straight forward: the reason the state of many African nations are in the state they are. You can imagine it being a very personal subject to many-an African director but Sissako handles it very well and it resonates; the film is not about one nation, despite having the capital of a certain nation as its title, but rather the state of a continent as a whole and the director doesn't focus on individual nations but gives everybody a voice.

The courtroom of the title it has been released as here and there is really nothing more than a patch of sandy land in the middle of an urban area. The officials are all dressed smartly and each of them are both French and Caucasian. It's here I think Sissako places the audience into the bodies of these officials, those that are of a 'Western' origin more than anything and those that must stand and listen to the African villagers state their cases to do with living conditions as well as both quality and amount of facilities they have available to them. It's here we feel as naive as the court officials, perhaps as humbled as they are when people give their statements and accounts some are loud and angry with a woman peeling off all these facts and figures for our benefit whereas others are quieter and more humbling but one such individual cannot say anything at all and this may be the most upsetting for most viewers.

Perhaps there is a certain irony behind the most effective 'statement' being one delivered by someone who doesn't say anything at all, given how the film likes its extended dialogue sequences. But I think that's down to good direction and good writing if anything: the timing of the silence within the piece. Through the statements, we find that the mere area is unhealthy and lacking medicine and places to earn a living, something that should rebound on us when thinking of the bigger picture and how this is one area in Mali we're dealing with, despite the hearing's overall link to the continent.

One cannot talk about the film without mentioning the bizarre manner in which it veers off out of the world it's taken so much time in establishing and into something else. About half way through the film, from memory, we begin watching a film within a film a daft looking Western starring Danny Glover which I suppose acts as the film's anchor around which the theme revolves. The western film is entitled 'Death in Timbuktu', a scathing reminder that 'death' is indeed happening all the time in Timbuktu, a town in Mali, more down to the malnutrition than trigger happy cowboys. It sees American and French actors/characters struggling to deal with their surroundings which is a wired hybrid of the Old West and a typical African village with sandy terrain, huts and everything else. The pit-stop could be seen as a metaphor for Americans, the French and Western economic powers in general struggling to deal with a 'problem' in Africa as lots of really unnecessary deaths keep happening again, in real life it's not death by a bullet as much as it is poor quality conditions.

What I like about Bamako more than, for instance, 'Waking Life' is its approach. We're not being talked down to here and we're not following some daft, trippy sequence of events that shows off what the latest computers are capable of. Instead, we have a real situation being presented to us and arguments established before events developed. This isn't a lecture or a 'talking down to' of the audience, this is reality made by someone who's been there and is producing a film that doubles as a statement. It won't be a film for everyone but the loose narrative to do with a breakup between two people offers us a fitting conclusion, an individual reduced to tears as the emotion floods to the surface as they realise not only their life but the verdict surrounding the hearing is in a purgatory and the only outcomes are two extremes either way.

This is an interesting film even though we know such a trial would never take place and if it did it wouldn't be in a public courtyard... that isn't really a problem though. The case raises some important issues about how African nations are treated however it does feel too polemic at times; this is especially the case when a French lawyer rails against the World Bank, the IMF and the west in general towards the end... the earlier more personal testimonies from affected Africans felt far more relevant. I liked the little details away from the details of the trail; a policeman has his gun stolen while he had a nap; a singer plans to move to Senegal and locals watch 'Death in Timbuktu', a pseudo-spaghetti western starring Danny Glover... this section was particularly inventive as we switch to watching this film within the film for several minutes. Overall I'd say this was fairly interesting but I felt it would have been more interesting if we'd seen more of people's ordinary lives and a little less of the trial.

There is a whole panoply of characters a beautiful queen bee (an example of the grace and poise of African women), Melé (Aissa Maiga) and her husband Chaka (Tiecoura Traore). Melé's a popular singer whose marriage is disintegrating and two of her spirited songs are integrated into the film. People watch TV, and the director ironically injects into his film a "western" set in Timbukto, in which incongruous white men as well as Palestinian director Elia Suleiman and Bamako's producer Danny Glover shoot each other. The effect is grotesque, but that's the point: why should Africans be watching TV westerns? Elsewhere on the earthy "set" of the film there's a young man, also beautiful, who lies dying inside a nearby building with no medical care. There are many children, some playing about, some being breast-fed. A couple marry, and the festivities interrupt the trial. There's a flinty gatekeeper who decides who can come in and who can't. There's a traditional griot who's one of the "witnesses" and who ends the proceedings with a hypnotic chant (not translated, but strangely stirring and stunning). There's another "witness" a former schoolteacher so hopelessly demoralized he refuses to utter a word; a sound recordist; a video photographer who says he prefers to take pictures of the dead because they're more real; and many authentic-looking extras, including a variety of dried-up tough young-old (or ageless) stick-men, all of them coming and going.

You get a vivid sense from all this, which is rhythmically inter-cut with the trial itself, of the harmonious seeming chaos of African village life; the color, the beauty and dignity of the people. You get above all a sense that life goes on. There are two white men on the "stage" of the trial, one an advocate for the international organizations (Roland Rappoport) and the other (William Bourdon) eloquently speaking for the African people and for socialism who concludes that the first world should be sentenced "to community service" "forever." Eloquent though he is, a Malian woman lawyer who speaks after him (Aissata Tall Sall) is more touching.

Like An Inconvenient Truth, Bamako's trial presents facts and arguments of enormous present day importance this time surrounding not global warming and the disintegration of the earth's eco-system, but another set of the planet's major problems: the social imbalances, the domination of the many by the few; poverty and disease, "terrorism" used to excuse world domination, the richest nations' doing harm while seeming to do good; the ravages of globalization, the privatization of natural resources down to land and water, perhaps ultimately to air; the national debts of poor nations collected by the economic organizations of the rich ones, and thereby preventing the poor ones from gaining any ground against the ravages of poverty and underdevelopment. .

This is powerful stuff. Sisako is, in theory, presenting both sides of the story, though it is obviously which side he is on and which side is in the majority on screen. This is polemic. The international organizations obviously aren't overtly setting out to destroy Africa are they? It is preaching; but it is done in a rich and colorful and dramatically moving way. The film picked up a US distributor during the New York Film Festival. It's not clear whether the way the print was presented was accurate. This seemed to be a projection of a digital copy that lost the surface beauty of the original. The colors of Jacques Besse's photography were beautiful, but dimmed. In French and Bambara (the Malian language).

Watching the film, we witness a debate between parties over the accumulated debt owed to the World Bank, IMF, and other "foreign aid" and the subjugating and anti-progressive cycle, in which they are now stuck, taking place in a courtyard of Bamako, Mali. The people of the court consist of both actors and actual activists (a style of mixed film-making innovated by Werner Herzog and continually popularized by Harmony Korine). The trial, performed in the traditionally Western means of democracy, takes place in the midst of surviving African tradition and culture. Director Sissako further implements with increased power his argument against the discussed globalization with this reconciliation and at times even presents the hilarity of their coexistence (i.e. - the fact this is in a courtyard and not a courtroom, the elderly man who expects to be heard in his culture without permission to speak by a judge, the toddler's squeaking shoes sounding off throughout eloquent speeches).

One of the most interesting creative decisions of the film-making was the stylish inclusion of a film within the film, an ironic western starring Danny Glover, also a producer of the film, and Palestinian director Elia Suleiman. Here again Sissako makes multiple uses of an item, here with paralleling metaphors of pillaging bad guys as well as humorous parody of non-American westerns (popularized in Cambodia and Thailand (see Tears of the Black Tiger, a homage to Thai westerns in the 1950s), though I am unsure if this is truly a popular genre of Mali). Sissako has also admitted that he chose a multi-ethnic cast for the western in illustrating that it was not solely the West to be blamed for the troubles of Africa. I also see that many of the other users' comments show that they missed the intent of this scene, possibly because they don't expect such leveled humor from primitive Africa (racists!).

As a film geek, I could continue to shower the film in technical praise: the documentary style of filming adding a greater objectivity to the story, the beautiful shots like the man reclining beneath the rusty amplifier, sounding the song of the old man in court, the silent testimony of the schoolteacher, etc. However, I will stay objective in discussion of the film's politics. The film's points are clear. The foreign solution to poverty increased Mali's poverty due to privatization and lost government jobs. The foreign solution to its economic growth has hindered such growth by creating a structure dependent on exports and suffocating it with the accumulating interest of the debt. The sad excuse for a reduction of the debt is laughable as a solution. In other words, the cowboys were shooting aimlessly at nothing.

Did you know

- GoofsDuring the inset "Death in Timbuktu" "western," just before the first gunshot, a car can be seen moving between two buildings in the background. This, however, could be interpreted as intentional by the director, who was parodying non-Western interpretations of a "western" (other countries who partake in a love of westerns are Thailand and Cambodia). The child in this scene is also wearing a Nike shirt. The effect is to present the sort of low-budget, pulp film one might see in a television broadcast in Mali, while supplying a metaphor to the actual movie's plot.

- Quotes

Avocat partie civile: We cannot throw Paul Wolfowitz into the Niger. The caimans wouldn't want him.

- How long is Bamako?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box office

- Budget

- €2,000,000 (estimated)

- Gross US & Canada

- $112,351

- Opening weekend US & Canada

- $10,183

- Feb 18, 2007

- Gross worldwide

- $1,059,232

- Runtime1 hour 55 minutes

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.85 : 1

Contribute to this page