IMDb RATING

6.9/10

1.6K

YOUR RATING

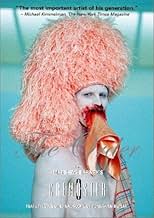

The third film of a five-part art-installation epic -- it's part-zombie movie, part-gangster film.The third film of a five-part art-installation epic -- it's part-zombie movie, part-gangster film.The third film of a five-part art-installation epic -- it's part-zombie movie, part-gangster film.

Peter Donald Badalamenti II

- Fionn MacCumhail

- (as Peter D. Badalamenti)

Todd Christian Hunter

- Mason

- (as Todd Hunter)

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

This film is painfully boring! It's also way too long. It was so bad that I started staring at the walls and ceiling of the theater rather than look at the screen. Not one moment of each inexplicable sequence really resonated with me in the slightest. I think at least eight or more people left the theater before it was finished.

There is no plot at all. That in itself doesn't bother me, I don't think that a film necessarily has to have a narrative structure. However, the way in which this was done just didn't work for me. I've seen a lot of comparisons to David Lynch in people's comments. I personally don't see it. I love most of Lynch's films.

It seemed like the sort of film that an autistic person would make, cold and lifeless with no discernible emotion. The film treats inanimate objects and people almost as if they were the same. There is very little humanity or empathy to be found anywhere. Not to mention that there's no dialog.

I just couldn't relate to it at all.

There is no plot at all. That in itself doesn't bother me, I don't think that a film necessarily has to have a narrative structure. However, the way in which this was done just didn't work for me. I've seen a lot of comparisons to David Lynch in people's comments. I personally don't see it. I love most of Lynch's films.

It seemed like the sort of film that an autistic person would make, cold and lifeless with no discernible emotion. The film treats inanimate objects and people almost as if they were the same. There is very little humanity or empathy to be found anywhere. Not to mention that there's no dialog.

I just couldn't relate to it at all.

I suppose you have to have already made a decision about who you a re and how cinema fits in your life to lucidly decide the first things about this. What is it and how will it speak to you?

I've now seen the "long" version and a 30 minute cut that was apparently done for exhibiting at The Guggenheim for patrons with less patience. Actually, with a different score that short version would be something useful. It isn't that the score is offensive. It is, but that's not what I'm trying to avoid. (Bjork's handling of "Restraint" was apt while annoying.) What he needs is something that plays with his symbol-universe sonically.

The short version cuts out the whole Chrysler erection sequence and shortens the Guggenheim. There's less Crisco tossing.

You may like this. It reeks of importance. It has layers of symbology, at least so far as notations and is very much like those paintings from that era when you could say: those grapes "stand for" so and so and that reclining lamb next to them "means" such and such. So okay: scots freemasonry as dedeconstruction, punk fried eggs, Dante's circles of museum hell, manufactured women except one beast goddess...

It seems for some of these he comes up with the symbol systems first, then surveys what material he has and then forms a performance out of that based on objects and himself. That's weak tea for me. "Cremaster 1" was an important and rich experience for me. That's because I believe he started with the images and built everything around that. Its really quite brilliant and I recommend it to you.

But not this. Its his own yard sale. Don't go.

Ted's Evaluation -- 1 of 3: You can find something better to do with this part of your life.

I've now seen the "long" version and a 30 minute cut that was apparently done for exhibiting at The Guggenheim for patrons with less patience. Actually, with a different score that short version would be something useful. It isn't that the score is offensive. It is, but that's not what I'm trying to avoid. (Bjork's handling of "Restraint" was apt while annoying.) What he needs is something that plays with his symbol-universe sonically.

The short version cuts out the whole Chrysler erection sequence and shortens the Guggenheim. There's less Crisco tossing.

You may like this. It reeks of importance. It has layers of symbology, at least so far as notations and is very much like those paintings from that era when you could say: those grapes "stand for" so and so and that reclining lamb next to them "means" such and such. So okay: scots freemasonry as dedeconstruction, punk fried eggs, Dante's circles of museum hell, manufactured women except one beast goddess...

It seems for some of these he comes up with the symbol systems first, then surveys what material he has and then forms a performance out of that based on objects and himself. That's weak tea for me. "Cremaster 1" was an important and rich experience for me. That's because I believe he started with the images and built everything around that. Its really quite brilliant and I recommend it to you.

But not this. Its his own yard sale. Don't go.

Ted's Evaluation -- 1 of 3: You can find something better to do with this part of your life.

Glen Helfand of The Guardian was particularly astute in likening Matthew Barney's "Cremaster" films to the 'Star Wars' films. While most 'Star Wars' fanatics would walk out on the "Cremaster" films, these works, like Lucas' series, create a completely new and strange world, with each subsequent film exploring and elaborating that world.

It's easy and lazy to dismiss Barney's work as pretentious. Of course it's pretentious. It's also important. What Barney is doing is taking arcane symbols, myths and images (related to Mormonism, Freemasonry, the reproductive system, historical figures, geographic locations, etc) and making them more arcane by using them as not only the motifs in his films, but the foundations. This is pure cinematic mutation, as Barney assembles these symbols and elements and does with them what David Cronenberg does with flesh and metal. Humans and objects in The Cremaster Cycle do not behave in a recognizable way. They interact with one another in a manner that goes beyond ritualism into the realm of necessity. They're partaking in processes, not performing rituals. As The Loughton Candidate in "Cremaster 4" tap-dances his way into a womb-like tunnel inside the earth under the Isle of Man, or as a character known as 'Goodyear' incubates in a dirigible while eating grapes and excreting them through her shoe in "Cremaster 1," one realizes that these human-like figures are more like insects in their behavior. The Cremaster Cycle establishes a world in which human beings and objects behave without will, like the cells in our body or the neurons in our brain.

"Cremaster 3," three hours long, is the last film in the five-part Cremaster Cycle, and serves as a culmination -- Barney explained that he wished for the Cycle to end in the middle, as though overlooking the other two films in the series as a skyscraper might. Incidentally, one of the two primary locations used in "Cremaster 3" is The Chrysler Building, which is given a sinister, demonic presence here (as in "The Caveman's Valentine" -- what is it about the Chrysler Building?) as it becomes a vessel for all sorts of grisly goings-on. A protracted demolition derby sequence set in the Chrysler building lobby depicts a gang of five late '60s model Chryslers pummeling a vintage Chrysler, intercut by scenes of the renovation of the building's exterior -- drawing a parallel between violence and progress. The curious achievement of this sequence is that it's brutally violent and eventually hard to stomach, yet its violence is amongst vehicles, not living beings.

"Cremaster 3" is beautifully scored by Jonathan Bepler, with some arresting interactions between the music and the images. An intermission occurs at the halfway point, before which the narrative builds to a near-climax of overwhelming power (another such climax closes the film), another surprising accomplishment given Cremaster's completely alien course of events. And Barney's idea of parody is to dehumorize slapstick comedy by making it eerie, in a bar scene (redolent of Kubrick's 'The Shining') featuring the underused and distinctive-looking Terry Gillespie.

It's easy and lazy to dismiss Barney's work as pretentious. Of course it's pretentious. It's also important. What Barney is doing is taking arcane symbols, myths and images (related to Mormonism, Freemasonry, the reproductive system, historical figures, geographic locations, etc) and making them more arcane by using them as not only the motifs in his films, but the foundations. This is pure cinematic mutation, as Barney assembles these symbols and elements and does with them what David Cronenberg does with flesh and metal. Humans and objects in The Cremaster Cycle do not behave in a recognizable way. They interact with one another in a manner that goes beyond ritualism into the realm of necessity. They're partaking in processes, not performing rituals. As The Loughton Candidate in "Cremaster 4" tap-dances his way into a womb-like tunnel inside the earth under the Isle of Man, or as a character known as 'Goodyear' incubates in a dirigible while eating grapes and excreting them through her shoe in "Cremaster 1," one realizes that these human-like figures are more like insects in their behavior. The Cremaster Cycle establishes a world in which human beings and objects behave without will, like the cells in our body or the neurons in our brain.

"Cremaster 3," three hours long, is the last film in the five-part Cremaster Cycle, and serves as a culmination -- Barney explained that he wished for the Cycle to end in the middle, as though overlooking the other two films in the series as a skyscraper might. Incidentally, one of the two primary locations used in "Cremaster 3" is The Chrysler Building, which is given a sinister, demonic presence here (as in "The Caveman's Valentine" -- what is it about the Chrysler Building?) as it becomes a vessel for all sorts of grisly goings-on. A protracted demolition derby sequence set in the Chrysler building lobby depicts a gang of five late '60s model Chryslers pummeling a vintage Chrysler, intercut by scenes of the renovation of the building's exterior -- drawing a parallel between violence and progress. The curious achievement of this sequence is that it's brutally violent and eventually hard to stomach, yet its violence is amongst vehicles, not living beings.

"Cremaster 3" is beautifully scored by Jonathan Bepler, with some arresting interactions between the music and the images. An intermission occurs at the halfway point, before which the narrative builds to a near-climax of overwhelming power (another such climax closes the film), another surprising accomplishment given Cremaster's completely alien course of events. And Barney's idea of parody is to dehumorize slapstick comedy by making it eerie, in a bar scene (redolent of Kubrick's 'The Shining') featuring the underused and distinctive-looking Terry Gillespie.

Though Matthew Barney doesn't identify himself as a filmmaker per se -- he's a sculptor by training and practice -- his Cremaster Cycle has me convinced that he has a more expansive vision for the possibility of cinema than any new director since Godard grabbed the audience by the hair and pulled us behind the camera with him.

I think part of Barney's resistance to the filmmaker label is that, like the rest of the world, he's been conditioned to believe that movies are only intended to serve a limited set of purposes, namely to act as filmed imitations of ankle-deep novels or plays; that a literal narrative, propelled throughout by actors talking, is the essential element of any movie. This model has been so deeply embedded in all of our psyches that even when a guy like Barney says "f*&^k all that" and defies every conceivable convention, he still feels as though he's doing something which is only nominally a film, even if it is in fact the opposite: a fully realized motion picture experience.

For those who don't know, The Cremaster Cycle is Barney's dreamlike meditation on ... well, I guess it'd be up to each viewer to decide exactly what the topics are, since the movies deliberately make themselves available for subjective interpretaton. Clearly Barney has creation and death on his mind, as well as ritual, architecture and space, symbolism, gender roles, and a Cronenbergian fascination with anatomy.

The movies are gorgeously photographed in settings that could only have been designed by someone with the eye of a true visual artist. In the first half of "3," Barney reimagines the polished interiors of the Chrysler Building as a temple in which the building itself is paradoxically conceived. The second half, slightly more personal, has Barney's alter ego in garish Celtic dress scaling the interior of a sparse Guggenheim Museum, intersecting at its various levels what are presumably various stages of his own artistic preoccupations -- encounters with dancing girls, punk rock, and fellow modern artist Richard Serra, among others.

In the end, what kind of movie is it? It certainly isn't the kind of movie that'll have Joel Silver sweating bullets over the box-office competition. Nor is it likely that more than three or four Academy members will see it, though nominations for cinematography and art direction would be well-deserved. It sure isn't warm and fuzzy: for my money, it might be a little too designed, too calculated. I always prefer chaotic naturalism over studious control. Friedkin over Hitchcock for me. It *is* the kind of movie that the most innovative mainstream filmmakers will talk about ten and twenty years from now when asked what inspired them. Barney's willingness to work entirely with associative imagery, to spell out absolutely nothing, and to let meaning take its first shape in the viewer's imagination, is the kind of catalyst that gives impressionable young minds the notion they can do something they didn't before think possible.

I think part of Barney's resistance to the filmmaker label is that, like the rest of the world, he's been conditioned to believe that movies are only intended to serve a limited set of purposes, namely to act as filmed imitations of ankle-deep novels or plays; that a literal narrative, propelled throughout by actors talking, is the essential element of any movie. This model has been so deeply embedded in all of our psyches that even when a guy like Barney says "f*&^k all that" and defies every conceivable convention, he still feels as though he's doing something which is only nominally a film, even if it is in fact the opposite: a fully realized motion picture experience.

For those who don't know, The Cremaster Cycle is Barney's dreamlike meditation on ... well, I guess it'd be up to each viewer to decide exactly what the topics are, since the movies deliberately make themselves available for subjective interpretaton. Clearly Barney has creation and death on his mind, as well as ritual, architecture and space, symbolism, gender roles, and a Cronenbergian fascination with anatomy.

The movies are gorgeously photographed in settings that could only have been designed by someone with the eye of a true visual artist. In the first half of "3," Barney reimagines the polished interiors of the Chrysler Building as a temple in which the building itself is paradoxically conceived. The second half, slightly more personal, has Barney's alter ego in garish Celtic dress scaling the interior of a sparse Guggenheim Museum, intersecting at its various levels what are presumably various stages of his own artistic preoccupations -- encounters with dancing girls, punk rock, and fellow modern artist Richard Serra, among others.

In the end, what kind of movie is it? It certainly isn't the kind of movie that'll have Joel Silver sweating bullets over the box-office competition. Nor is it likely that more than three or four Academy members will see it, though nominations for cinematography and art direction would be well-deserved. It sure isn't warm and fuzzy: for my money, it might be a little too designed, too calculated. I always prefer chaotic naturalism over studious control. Friedkin over Hitchcock for me. It *is* the kind of movie that the most innovative mainstream filmmakers will talk about ten and twenty years from now when asked what inspired them. Barney's willingness to work entirely with associative imagery, to spell out absolutely nothing, and to let meaning take its first shape in the viewer's imagination, is the kind of catalyst that gives impressionable young minds the notion they can do something they didn't before think possible.

This movie is THREE HOURS LONG. I tried, I really tried to understand what the hell was going on, but this epic, incomprehensible art film is nearly impossible to follow, even if you've read the synopsis on the cremaster.net website. There are a lot of visually interesting images, the "car crash" scene and the "dentures" scene being particularly strange and disturbing, but I kept looking at my watch wondering when this awful movie was going to end. However, I can't give it a 3 or a 4, because some of the images, like teeth traveling through intestines, and the leopard lady, are stunning and strange, so I'll be generous and give it 5 out of 10. But I can't recommend it to anyone but the arty elite. When it finished, I got up and said "Thank God that's over!"

Did you know

- GoofsAfter the teeth have begun to exit the Apprentice's prolapsed intestine, there is an overhead shot of the hitmen standing around the Apprentice on the dentist's chair. The view of the intestine is slightly blocked by the back of one of the hitmen, but as he shifts from side to side, the teeth are nowhere to be seen.

- ConnectionsEdited into The Cremaster Cycle (2003)

- How long is Cremaster 3?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box office

- Gross US & Canada

- $120,308

- Opening weekend US & Canada

- $9,787

- May 21, 2010

- Runtime

- 3h 2m(182 min)

- Color

- Sound mix

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content