A 15-year-old Long Island boy loses everything and everyone he knows, soon becoming involved in a relationship with a much older man.A 15-year-old Long Island boy loses everything and everyone he knows, soon becoming involved in a relationship with a much older man.A 15-year-old Long Island boy loses everything and everyone he knows, soon becoming involved in a relationship with a much older man.

- Director

- Writers

- Stars

- Awards

- 20 wins & 18 nominations total

Paul Dano

- Howie Blitzer

- (as Paul Franklin Dano)

Tony Michael Donnelly

- Brian

- (as Tony Donnelly)

Frank Rivers

- Man with Pizza

- (as Frank G. Rivers)

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

'I needed to make a movie that stayed with people emotionally and psychologically' says L.I.E. director Michael Cuesta. The result, his debut, bears all the hallmarks of a quietly assured, minor modern classic. As Brian Cox, who plays L.I.E's big-hearted pederast 'Big John' Harrigan, says, 'It's old-fashioned in many ways, a film that takes its time and doesn't suffer from MTV jump-cutting'. Such subtleties cut no slack with US censors, who saddled it with a damaging and unsuccessfully appealed NC-17 rating. A knee-jerk reaction, its distributors argued, 'to a small grab-bag of wholly misunderstood moments.infinitely less graphic and gratuitous than many dozens of other films given R ratings.' Despite its sole depiction of nudity being a three-second shot of a (rampantly heterosexual) male buttock, 17-year-old filmgoers were legally obliged to view this intricate study of suburban dislocation with their bemused guardians in tow - a dictate distributors optimistically steered to their advantage. L.I.E's searingly honest exploration of adolescence might now become 'a unique opportunity for a meaningful dialogue' between parents and teens. An unlikely occurrence in the main, given its fleeting, near-invisible cinematic outing.

L.I.E stands for Long Island Expressway, a commuter-crowded freeway running like a knife slash through an affluent New York suburb; for Cuesta 'a metaphor for a kid who's about to be sent into the scary world of adulthood regardless of whether he's ready or not'. A hazardous route then which, we learn, has already killed 'Cat's in the Cradle' singer/songwriter Harry Chapin, All the President's Men director Alan J Pakula - and the mother of L.I.E.'s 15-year-old Howie (a remarkable performance of put-on adolescent toughness, vulnerability and knowing from Paul Franklin Dano). The 'lie' of the title symbolising the myth of cosy suburbia but more pertinently, the casual or far-reaching deceits L.I.E.'s guilt-edged cast of slack-jawed wide boys, footloose rent boys, corrupt white-collar contractors and 'always ashamed' Chicken Hawks will visit on themselves and one another, emotionally hobbled, or shot-through with grief, every one.

If L.I.E initially drew comparisons with the work of Harmony Korine, Larry Clark - and Todd Solondz in particular, Cuesta's film contains a warmth and delicacy often lacking from these fellow chroniclers of suburban juvenile woe. The semi-autobiographical script, by Stephen M Ryder and Michael and Gerald Cuesta, is kinda different too - frank without being exploitative, and unexpectedly tender, with no pussyfooting at all. As Cox says, 'original, brave - kind of groundbreaking'. While that old stand-by of Indiedom, the roving hand-held is present and correct, if refreshingly unobtrusive, Romeo Tirone's exquisite cinematography further distinguishes L.I.E. from its sullen contemporaries, combining a stark, saturated quality (most effectively for the sterile look of soulless 1980s houses) with the smooth visual finish of a Michael Mann.

Perhaps its nearest equivalent is David O Russell's taboo-fest from 1994, Spanking the Monkey, another portrait of inter-generational relationships (plain old incest in this case) played out against the backdrop of suburban blitz - long a fertile slouching ground for independent filmmakers. As former photographer Cuesta, a Long Island native, whose boyhood memories brought a lot to bear on the film's innate truthfulness, says: 'Suburbs have their own cultures, rhythms, ethics, and morals.you have everyone from the Mafia to the artists to 9-5 commuters, and it's certainly true that there's a story behind every door and at the end of every driveway. A big part of making L.I.E. feel real had to do with the inherent realism that comes with shooting near a major highway. That constant hum of traffic permeates every neighbourhood - everyone deals with that sound.'

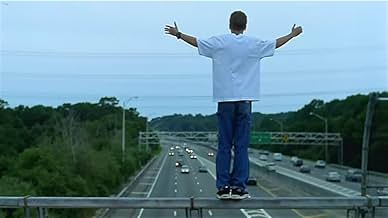

We first encounter Howie teetering on the brink of a burgeoning, ambivalent sexuality. Literally teetering, as the opening shot describes, balanced precariously on the edge of a flyover. Abandoned by everyone - his father, friends, and schoolboy crush Gary (a shimmeringly anarchic Billy Kay) the sensitive Howie finds emotional rescue with the mysterious 'Big John' Harrigan. An exuberant bear of a man, a curious Harrigan attempts to bewitch an amusedly reticent Howie with allusions to a thrillingly glamorous past, man and boy engaged in teasing, fumbling power play - until an unlikely, neo-parental alliance is at first grudgingly, then preciously forged.

'It was vital the audience could relate to Big John, even sympathize with him', says Cuesta. '(But) I tried very hard to make sure his intentions were constantly blurred'. For Cox, the role (one of his greatest performances) was 'potentially, a career-burying move. There were enormous dangers in it. But I weighed up the odds - and decided the whole point of not doing it were the very reasons to do it. I was really intrigued by how far one could take the character and make it work. The first trap an actor could fall into would be to play Big John as a man whose public façade disguised the fact he was a sexual predator. I took the opposite view: that he was this wonderfully open character, and actually a very nice man - who happened to be a pederast. And the range became so much bigger. It's a story of redemption, and that's what finally came through for me. It's a very responsible film.'

L.I.E stands for Long Island Expressway, a commuter-crowded freeway running like a knife slash through an affluent New York suburb; for Cuesta 'a metaphor for a kid who's about to be sent into the scary world of adulthood regardless of whether he's ready or not'. A hazardous route then which, we learn, has already killed 'Cat's in the Cradle' singer/songwriter Harry Chapin, All the President's Men director Alan J Pakula - and the mother of L.I.E.'s 15-year-old Howie (a remarkable performance of put-on adolescent toughness, vulnerability and knowing from Paul Franklin Dano). The 'lie' of the title symbolising the myth of cosy suburbia but more pertinently, the casual or far-reaching deceits L.I.E.'s guilt-edged cast of slack-jawed wide boys, footloose rent boys, corrupt white-collar contractors and 'always ashamed' Chicken Hawks will visit on themselves and one another, emotionally hobbled, or shot-through with grief, every one.

If L.I.E initially drew comparisons with the work of Harmony Korine, Larry Clark - and Todd Solondz in particular, Cuesta's film contains a warmth and delicacy often lacking from these fellow chroniclers of suburban juvenile woe. The semi-autobiographical script, by Stephen M Ryder and Michael and Gerald Cuesta, is kinda different too - frank without being exploitative, and unexpectedly tender, with no pussyfooting at all. As Cox says, 'original, brave - kind of groundbreaking'. While that old stand-by of Indiedom, the roving hand-held is present and correct, if refreshingly unobtrusive, Romeo Tirone's exquisite cinematography further distinguishes L.I.E. from its sullen contemporaries, combining a stark, saturated quality (most effectively for the sterile look of soulless 1980s houses) with the smooth visual finish of a Michael Mann.

Perhaps its nearest equivalent is David O Russell's taboo-fest from 1994, Spanking the Monkey, another portrait of inter-generational relationships (plain old incest in this case) played out against the backdrop of suburban blitz - long a fertile slouching ground for independent filmmakers. As former photographer Cuesta, a Long Island native, whose boyhood memories brought a lot to bear on the film's innate truthfulness, says: 'Suburbs have their own cultures, rhythms, ethics, and morals.you have everyone from the Mafia to the artists to 9-5 commuters, and it's certainly true that there's a story behind every door and at the end of every driveway. A big part of making L.I.E. feel real had to do with the inherent realism that comes with shooting near a major highway. That constant hum of traffic permeates every neighbourhood - everyone deals with that sound.'

We first encounter Howie teetering on the brink of a burgeoning, ambivalent sexuality. Literally teetering, as the opening shot describes, balanced precariously on the edge of a flyover. Abandoned by everyone - his father, friends, and schoolboy crush Gary (a shimmeringly anarchic Billy Kay) the sensitive Howie finds emotional rescue with the mysterious 'Big John' Harrigan. An exuberant bear of a man, a curious Harrigan attempts to bewitch an amusedly reticent Howie with allusions to a thrillingly glamorous past, man and boy engaged in teasing, fumbling power play - until an unlikely, neo-parental alliance is at first grudgingly, then preciously forged.

'It was vital the audience could relate to Big John, even sympathize with him', says Cuesta. '(But) I tried very hard to make sure his intentions were constantly blurred'. For Cox, the role (one of his greatest performances) was 'potentially, a career-burying move. There were enormous dangers in it. But I weighed up the odds - and decided the whole point of not doing it were the very reasons to do it. I was really intrigued by how far one could take the character and make it work. The first trap an actor could fall into would be to play Big John as a man whose public façade disguised the fact he was a sexual predator. I took the opposite view: that he was this wonderfully open character, and actually a very nice man - who happened to be a pederast. And the range became so much bigger. It's a story of redemption, and that's what finally came through for me. It's a very responsible film.'

As a sexuality educator I was impressed by the straightforward, nonjudgmental nature of a rather difficult topic. I vacillated between giving this film an 8 or a 9 and decided on 9 because we need more films like this. This topic requires understanding, not acceptance mind you, but real honest understanding. The very fact that it was given an nc-17 rating is part of the problem with our society. There was about as much sex as I've seen in R or even PG-13 movies, the rating was obviously ONLY because of the uncomfortable subject matter. How can society solve a problem that it clearly does not even want to talk about, let alone understand?

On the Long Island Expressway, Howie says, "You got your lanes going east, you got your lanes going west, and you got your lanes going straight to hell". Perched on a barrier above the Long Island Expressway ready to jump, 15 year old Howie Blitzer (Paul Franklin Dano) tells us that the L.I.E. has claimed many lives including folk singer Harry Chapin, film director Alan J. Pakula, and Howie's mother in a recent car crash. Now scared and alone, emotionally distant from his sleazy, corrupt father, and having fallen in with a gang of thieves and male prostitutes, Howie is poised to become the next victim of the Expressway.

L.I.E. is the coming of age story of a boy who must quickly develop resiliency to cope with the loss of the things closest to him; his mother to the L.I.E., his father to the criminal justice system, and his best friend Gary to the lure of California. More real than American Beauty, more honest than Ghost World, less sleazy than Kids or Happiness, L.I.E. is a tender and thoughtful, often funny, examination of the lives of suburban teens who are without guidance or adult role models and who must develop inner strength simply in order to survive.

Like taking drugs to numb the pain of their boredom and loneliness, Howie, his friend Gary, and a few others have been robbing the expensive houses of their Long Island neighbors just for the excitement of seeing how much they can get away with. One of their escapades takes them to the house of Big John Harrigan (brilliantly performed by Scottish actor Brian Cox), a macho ex-marine well known in the neighborhood as a chickenhawk (for those uninitiated, an individual with a predilection for sex with young men). This encounter is a turning point for young Howie.

Howie and Big John develop a relationship which, while the possibility of man-boy sex is clearly implied, is not threatening or exploitative, but provides Howie with the substitute father-figure he so desperately needs. In portraying Big John, first time director, Michael Cuesta resists moralizing and courageously defies stereotyping. (NOTE: in reality, the sexual predator is more likely to be an inconspicuous business or professional man who uses sex in a furtive manner to satisfy some unfilled need, not the flamboyant, in-your-face sleaze ball that Big John represents).

Paul Franklin Dano as Howie completely captures the confusion and neediness of a lonely teen trying to discover who he is, and he is very reminiscent of a young River Phoenix. Howie comes alive as an immature, lonely, and sexually confused teen, yet a sensitive and intelligent individual who writes poetry to give voice to his loneliness. Howie startles Big John with his knowledge of Chagall and quotes this Walt Whitman strain from Leaves of Grass to him while riding in his car:

"Never more the cries of unsatisfied love be absent from me, Never again leave me to be the peaceful child I was before what there, in the night, By the sea, under the yellow and sagging moon, The messenger there arous'd-the fire, the sweet hell within, The unknown want, the destiny of me."

It is uncertain until the end whether Howie will succumb to the forces closing in on him or develop the inner strength to cope with his loss.

This movie has caused some consternation in some quarters because it shows a sexual predator as a complex human being with feelings. Cuesta does not advocate man-boy relationships but does show that these relationships can often be based on mutual need, something some may overlook when screaming "sexual abuse". Cuesta forces us to look at the multi-leveled components of the relationship, both the predator and the protector, the manipulator and the manipulated. The filmmaker presents the older man as he is, an exploiter with layers of self-hatred and shame, but also as a human being, capable of warmth and love. At the end, if nothing else, I sensed that Howie through his pit stop relationship with Big John was older, wiser, and much more capable of dealing with his problems.

Despite some poorly drawn characters (his father in particular is a caricature) and an oversimplified ending that would have been better left on the cutting room floor, I truly loved this film and would recommend it highly.

Stupidly rated NC-17, L.I.E. is a film that should be seen by both teenagers and their parents.

L.I.E. is the coming of age story of a boy who must quickly develop resiliency to cope with the loss of the things closest to him; his mother to the L.I.E., his father to the criminal justice system, and his best friend Gary to the lure of California. More real than American Beauty, more honest than Ghost World, less sleazy than Kids or Happiness, L.I.E. is a tender and thoughtful, often funny, examination of the lives of suburban teens who are without guidance or adult role models and who must develop inner strength simply in order to survive.

Like taking drugs to numb the pain of their boredom and loneliness, Howie, his friend Gary, and a few others have been robbing the expensive houses of their Long Island neighbors just for the excitement of seeing how much they can get away with. One of their escapades takes them to the house of Big John Harrigan (brilliantly performed by Scottish actor Brian Cox), a macho ex-marine well known in the neighborhood as a chickenhawk (for those uninitiated, an individual with a predilection for sex with young men). This encounter is a turning point for young Howie.

Howie and Big John develop a relationship which, while the possibility of man-boy sex is clearly implied, is not threatening or exploitative, but provides Howie with the substitute father-figure he so desperately needs. In portraying Big John, first time director, Michael Cuesta resists moralizing and courageously defies stereotyping. (NOTE: in reality, the sexual predator is more likely to be an inconspicuous business or professional man who uses sex in a furtive manner to satisfy some unfilled need, not the flamboyant, in-your-face sleaze ball that Big John represents).

Paul Franklin Dano as Howie completely captures the confusion and neediness of a lonely teen trying to discover who he is, and he is very reminiscent of a young River Phoenix. Howie comes alive as an immature, lonely, and sexually confused teen, yet a sensitive and intelligent individual who writes poetry to give voice to his loneliness. Howie startles Big John with his knowledge of Chagall and quotes this Walt Whitman strain from Leaves of Grass to him while riding in his car:

"Never more the cries of unsatisfied love be absent from me, Never again leave me to be the peaceful child I was before what there, in the night, By the sea, under the yellow and sagging moon, The messenger there arous'd-the fire, the sweet hell within, The unknown want, the destiny of me."

It is uncertain until the end whether Howie will succumb to the forces closing in on him or develop the inner strength to cope with his loss.

This movie has caused some consternation in some quarters because it shows a sexual predator as a complex human being with feelings. Cuesta does not advocate man-boy relationships but does show that these relationships can often be based on mutual need, something some may overlook when screaming "sexual abuse". Cuesta forces us to look at the multi-leveled components of the relationship, both the predator and the protector, the manipulator and the manipulated. The filmmaker presents the older man as he is, an exploiter with layers of self-hatred and shame, but also as a human being, capable of warmth and love. At the end, if nothing else, I sensed that Howie through his pit stop relationship with Big John was older, wiser, and much more capable of dealing with his problems.

Despite some poorly drawn characters (his father in particular is a caricature) and an oversimplified ending that would have been better left on the cutting room floor, I truly loved this film and would recommend it highly.

Stupidly rated NC-17, L.I.E. is a film that should be seen by both teenagers and their parents.

This story rings true because it's something that happens in the real world all the time, whether people want to admit it or not. The film captures events and emotions that are complex, challenging, and confusing.

Howie, a young, intelligent, good-looking boy attracts attention from the same sex and isn't sure how he feels about it. He meets "Big John", and finds himself fascinated and impressed by the man's life, flattered and a bit scared at the attention he shows, and also somewhat repulsed by the man's attraction for young boys.

John, for his part, begins the relationship from a position he's quite familiar with: using his power as a worldly and canny adult to manipulate someone else. He feels physically attracted to Howie, but as they spend more time together, he sees the depth of the boy's character and a sensitivity similar to his own. Howie brings out the good side in John (and some people may be shocked that the film shows how a pedophile can have a "good side", but this is reality and it is well depicted).

Howie's feelings are excellently illustrated as they run a wide spectrum: confused, repulsed, lonely, defiant, confident, aroused, at times even suicidal. I empathized with and admired the character, and found myself rooting strongly for him to rise above the tragic and frustrating circumstances in which he found himself. In the end I felt a sense of triumph as we saw that, despite his unfortunate situation and his own flaws and weaknesses, he does possess the strength and character to face the world and become his own person.

Howie, a young, intelligent, good-looking boy attracts attention from the same sex and isn't sure how he feels about it. He meets "Big John", and finds himself fascinated and impressed by the man's life, flattered and a bit scared at the attention he shows, and also somewhat repulsed by the man's attraction for young boys.

John, for his part, begins the relationship from a position he's quite familiar with: using his power as a worldly and canny adult to manipulate someone else. He feels physically attracted to Howie, but as they spend more time together, he sees the depth of the boy's character and a sensitivity similar to his own. Howie brings out the good side in John (and some people may be shocked that the film shows how a pedophile can have a "good side", but this is reality and it is well depicted).

Howie's feelings are excellently illustrated as they run a wide spectrum: confused, repulsed, lonely, defiant, confident, aroused, at times even suicidal. I empathized with and admired the character, and found myself rooting strongly for him to rise above the tragic and frustrating circumstances in which he found himself. In the end I felt a sense of triumph as we saw that, despite his unfortunate situation and his own flaws and weaknesses, he does possess the strength and character to face the world and become his own person.

I think that's the adjectivian phrase that i'm looking for to describe my reaction to this film. From the opening film scene to the abrupt end my eyes were like saucers as my head often shook side to side as if to say no. As a shrink who deals with children, this is an excellent examination of how many times there are no easy solutions and good kids can easily find themselves in bad straits. This is the best movie that I have seen in the past 3 years, which is quite a compliment since I attend movies regularly. I've warned fellow movie buffs of the strong content while suggesting that they look beyond that to examine what they think about the films commentary on teens developing their identities as they seek to enter into adulthood.

Did you know

- GoofsHowie doesn't have the earring in his cartilage during the fight with Marty and Kevin.

- Quotes

[Laying on the ground as a woman passes by]

Kevin Cole: Her dress is so short, you can see her clint.

Brian: What?

Kevin Cole: Her clint, it's in her pussy.

Howie: You mean "clit."

Kevin Cole: Fuck you, I mean like... clintasaurus.

Howie: It's clitoris, you fuckin' idiot.

Kevin Cole: It's a CLINT.

Brian: Yeah, like you can see Clint Eastwood in her pussy.

- Alternate versionsThe uncut version (originally rated NC-17) is available on DVD. It features a longer sex scene near the beginning.

- ConnectionsFeatured in The 2002 IFP/West Independent Spirit Awards (2002)

- SoundtracksLungo Fillaccio

Written and Performed by R. Cardinali

Dewolfe Music (ASCAP)

- How long is L.I.E.?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Release date

- Country of origin

- Official site

- Language

- Also known as

- L.I.E.

- Filming locations

- Production companies

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Box office

- Budget

- $700,000 (estimated)

- Gross US & Canada

- $1,138,836

- Opening weekend US & Canada

- $82,530

- Sep 9, 2001

- Gross worldwide

- $1,846,059

- Runtime1 hour 37 minutes

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.85 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content

Top Gap

By what name was L.I.E. Long Island Expressway (2001) officially released in Japan in Japanese?

Answer