Hitokiri

- 1969

- 2h 20m

IMDb RATING

7.4/10

1.3K

YOUR RATING

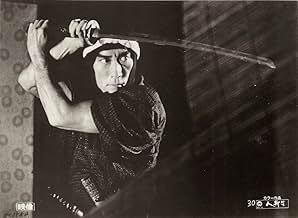

A destitute ronin allies himself with an established clan, but its ruthless leader tries to turn him into a mindless killer.A destitute ronin allies himself with an established clan, but its ruthless leader tries to turn him into a mindless killer.A destitute ronin allies himself with an established clan, but its ruthless leader tries to turn him into a mindless killer.

- Director

- Writers

- Stars

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

Hitokiri (which translates roughly as "assassination"), a/k/a "Tenchu" which translates roughly as "divine punishment") showcases Hideo Gosha at the top of his form. Do NOT miss this one, or Gosha's other classic, Goyokin! Hitokiri is not only one of Gosha's best films, it's one of the best "samurai/chambara" films ever made, and perhaps one of the best Japanese films ever exported.

Be warned, all of the intricate plot details in Hitokiri can be a little hard to follow for those unfamiliar with 19th century Japanese history. Even so, the underlying human drama is obvious to all viewers. As per the norm for Gosha, Hitokiri is yet another variation on his traditional theme of "loyalty to one's lord" vs. "doing the right thing". However, Gosha develops his favorite theme with such sophistication, that it's really _the_ movie to see (as a double-feature with Goyokin, of course!)

I suppose it breaks down like this: If you want a simpler, more action-oriented revenge tale, see Goyokin. However, if you want a more thoughtful, multilayered (albeit grim) historical drama, see Tenchu.

(OK, OK, essentially, Tenchu's historical backdrop is the massive power struggle between different samurai clans who are either (1) working to reform, yet preserve, the Tokugawa Shogunate, or (2) trying to install the Emperor Meiji as the supreme ruler of Japan. Of course, those clans working "for" Emperor Meiji were often less interested in "reforming" Japan than in ensuring their own clan more power in the "new world order". Ironically, the entire feudal system was officially abolished as one of the first reforms of the Meiji government. It's twists like this -- Gosha's big on irony -- that make the entire plot all the more bittersweet.)

What distinguishes "Hitokiri" from Gosha's other movies is Gosha's expert color cinematography. Every shot is thoughtfully composed, and (much like Kubrick's Barry Lyndon) each frame of the movie could hold its own as a still composition. Hitokiri really stands out with stunning backdrops, including(as with Goyokin) many riveting seascapes. Just watch the opening sequence, and you're hooked! Make no mistake, this is no Merchant-Ivory period piece: Hitokiri is extremely violent.

What else, other than cool camera work, makes Hitokiri stand out? The performances seem (to me) a bit more subtle in this one. Katsu Shintaro (of Zatoichi / Lone Wolf fame) turns in a star performance as the conflicted protagonist/antihero, Okada Izo. Katsu manages to instill humanity to a character that seems almost more wild animal than villain. Throughout the movie, you're never quite sure if you're engaged or revolted by Okada's character. At the same time, Katsu's portrayal of Okada's ravenous hunger for respect, and his later pathetic attempts at redemption, seem so human that you can't help but feel empathy/sympathy. Of course, after seeing Nakadai Tatsuya play the tortured hero in "Goyokin", it's great to see him play such a ruthless villain in "Hitokiri". He's just perfect, there's nothing more to say!

As a final note, perhaps more interesting to buffs than to casual fans, don't miss the last screen appearance of Mishima Yukio (yes, the closeted gay right-wing ultranationalist novelist who committed suicide by seppuku before the crowd of jeering Japanese military personnel he "kidnapped" in 1970, and had a movie on his life and work made by Paul Schrader), who actually does a pretty solid job of portraying the honorable (for an assassin) Shinbei Tanaka.

Be warned, all of the intricate plot details in Hitokiri can be a little hard to follow for those unfamiliar with 19th century Japanese history. Even so, the underlying human drama is obvious to all viewers. As per the norm for Gosha, Hitokiri is yet another variation on his traditional theme of "loyalty to one's lord" vs. "doing the right thing". However, Gosha develops his favorite theme with such sophistication, that it's really _the_ movie to see (as a double-feature with Goyokin, of course!)

I suppose it breaks down like this: If you want a simpler, more action-oriented revenge tale, see Goyokin. However, if you want a more thoughtful, multilayered (albeit grim) historical drama, see Tenchu.

(OK, OK, essentially, Tenchu's historical backdrop is the massive power struggle between different samurai clans who are either (1) working to reform, yet preserve, the Tokugawa Shogunate, or (2) trying to install the Emperor Meiji as the supreme ruler of Japan. Of course, those clans working "for" Emperor Meiji were often less interested in "reforming" Japan than in ensuring their own clan more power in the "new world order". Ironically, the entire feudal system was officially abolished as one of the first reforms of the Meiji government. It's twists like this -- Gosha's big on irony -- that make the entire plot all the more bittersweet.)

What distinguishes "Hitokiri" from Gosha's other movies is Gosha's expert color cinematography. Every shot is thoughtfully composed, and (much like Kubrick's Barry Lyndon) each frame of the movie could hold its own as a still composition. Hitokiri really stands out with stunning backdrops, including(as with Goyokin) many riveting seascapes. Just watch the opening sequence, and you're hooked! Make no mistake, this is no Merchant-Ivory period piece: Hitokiri is extremely violent.

What else, other than cool camera work, makes Hitokiri stand out? The performances seem (to me) a bit more subtle in this one. Katsu Shintaro (of Zatoichi / Lone Wolf fame) turns in a star performance as the conflicted protagonist/antihero, Okada Izo. Katsu manages to instill humanity to a character that seems almost more wild animal than villain. Throughout the movie, you're never quite sure if you're engaged or revolted by Okada's character. At the same time, Katsu's portrayal of Okada's ravenous hunger for respect, and his later pathetic attempts at redemption, seem so human that you can't help but feel empathy/sympathy. Of course, after seeing Nakadai Tatsuya play the tortured hero in "Goyokin", it's great to see him play such a ruthless villain in "Hitokiri". He's just perfect, there's nothing more to say!

As a final note, perhaps more interesting to buffs than to casual fans, don't miss the last screen appearance of Mishima Yukio (yes, the closeted gay right-wing ultranationalist novelist who committed suicide by seppuku before the crowd of jeering Japanese military personnel he "kidnapped" in 1970, and had a movie on his life and work made by Paul Schrader), who actually does a pretty solid job of portraying the honorable (for an assassin) Shinbei Tanaka.

This is one of the best of the genre. I saw it twice about 25yrs ago and have not had another opportunity to see it again since then. It rivals the Zatoichi series (also starring Katsu) in exciting swordplay.

9Jigo

Tenchu aka. Hitokiri- directed by Hideo Gosha - starring Shintaro Katsu and Tetsuya NAkadei belongs (together with Goyokin, HAra Kiri & Rebellion) to the best chambara movies existing.

Its the story about Shintaro Katsu (who plays Okada Izo) working for Nakadei, who wants to become the daymio. Okada, being the "cleaner" for Nakadei is being treated like a dog - and after quite a while he realises - what he realy is to Nakadei.

But there is so much more in this movie - every fan of japanese cinema should have seen it !!!!!!!

(Tenchu means Heavens Punishment)

Its the story about Shintaro Katsu (who plays Okada Izo) working for Nakadei, who wants to become the daymio. Okada, being the "cleaner" for Nakadei is being treated like a dog - and after quite a while he realises - what he realy is to Nakadei.

But there is so much more in this movie - every fan of japanese cinema should have seen it !!!!!!!

(Tenchu means Heavens Punishment)

Many of the lead characters in Hideo Gosha's 1969 film "Hitokiri" (manslayer; aka "Tenchu" — heaven's punishment) were actual historical figures (in "western" name-order format): Ryoma Sakamoto, Hampeita Takechi, Shimbei Tanaka, Izo Okada, (?) Anenokoji. The name "Hitokiri," a historical term, refers to a group of four super-swordsmen who carried out numerous assassinations of key figures in the ruling Tokugawa Shogunate in the mid-1800s under the orders of Takechi, the leader of the "Loyalist" (i.e. ultra-nationalist, pro-Emperor) faction of the Tosa clan. What was this struggle about? Sad to say, you won't find out in this film. "Brilliant History Lesson" indeed!

No, Gosha is much more interested in showing you the usual bloody slicing and dicing and (at absurd length) the inner torment of the not-very-bright killer Izo Okada than in revealing actual history. Sakamoto, for example, was someone of historical significance, considered to be the father of the Imperial Japanese Navy. The closest Gosha comes to providing a history lesson is the scene in which Sakamoto, whom Takechi considers a traitor to the Loyalist cause, comes to Takechi's compound to try to sway him ideologically. He begins by talking about the international political/military situation, with foreign warships in Japan's ports and a Japan that is too weak militarily to defend against them. Want to know more? Sorry. Gosha cuts off this potentially fascinating lecture in mid sentence(!). So much for informing his audience about a turning point in Japanese history.

The film left me in utter confusion about the aims of the two sides in this struggle. For the two and a half centuries that the Shogunate held central power in Japan, it was an institution dedicated to preventing social change, to preserving the feudal relations of society. It was fearful of outside contamination, both ideological and technological. In keeping with this spirit, it outlawed firearms, those instruments of "leveling" in Europe and the Americas, with which a peasant could have stood up to a samurai. Throughout this period, the Emperor was nothing more than a spiritual figurehead.

But, in the towns, which developed in neutral zones between the feudal fiefdoms, a new class of merchants, landlords and craftsmen was forming — the class widely known in Europe by its French name, the bourgeoisie. Inevitably, as this new class gained strength, it chafed against the many confines of feudal society. As in Europe, the king (Emperor) became the central figure in the bourgeoisie's struggle for power against the feudal aristocracy. But a political leadership does not always fully understand the interests of the class it serves. When the outside world arrived with a bang in 1853, in the form of U.S. Admiral Perry's "Black Ships," the ruling elite of Japan were thrown into a crisis. Their military was no match for these foreigners. Also, they had heard about the havoc the British and French imperialists were wreaking in China. What should Japan do to save itself from the fate of its weak neighbor? Surprisingly, some elements within the usually isolationist Shogunate were inclined to open trade with the foreigners in order to obtain some of their advanced technology. This is the point of view represented (just barely) in the film by Sakamoto. On the other hand, the Emperor-loyal ultra-nationalists, represented by Takechi, believed they could keep out the foreigners by force, if only they could prevent the other faction from "selling out the country." (Sound familiar?) Thus, the assassination of key Shogunate figures is in order — and away we go.

Takechi's motivations were, for me, the film's biggest puzzle. Gosha suggests that he is fighting mainly for his personal advancement rather than for the Loyalist cause. Can we take this to represent the tenor of the Loyalists as a whole? (Do you care?)

Several reviewers compared this film favorably with "Goyokin," which Gosha made in the same year. But, where "Goyokin" is a crackling, suspenseful, adventure yarn, with a hero worthy of sympathy, "Hitokiri" is plodding, nowhere near as compelling and lacks such a hero. Sakamoto could have been this film's hero but we are not allowed to know him — nor what he stands for — well enough for him to achieve that status.

In view of his wonderful scores for five previous Kurosawa films, Masaru Sato's score here was very disappointing, sounding like something rejected from a "Bonanza" episode.

Barry Freed

No, Gosha is much more interested in showing you the usual bloody slicing and dicing and (at absurd length) the inner torment of the not-very-bright killer Izo Okada than in revealing actual history. Sakamoto, for example, was someone of historical significance, considered to be the father of the Imperial Japanese Navy. The closest Gosha comes to providing a history lesson is the scene in which Sakamoto, whom Takechi considers a traitor to the Loyalist cause, comes to Takechi's compound to try to sway him ideologically. He begins by talking about the international political/military situation, with foreign warships in Japan's ports and a Japan that is too weak militarily to defend against them. Want to know more? Sorry. Gosha cuts off this potentially fascinating lecture in mid sentence(!). So much for informing his audience about a turning point in Japanese history.

The film left me in utter confusion about the aims of the two sides in this struggle. For the two and a half centuries that the Shogunate held central power in Japan, it was an institution dedicated to preventing social change, to preserving the feudal relations of society. It was fearful of outside contamination, both ideological and technological. In keeping with this spirit, it outlawed firearms, those instruments of "leveling" in Europe and the Americas, with which a peasant could have stood up to a samurai. Throughout this period, the Emperor was nothing more than a spiritual figurehead.

But, in the towns, which developed in neutral zones between the feudal fiefdoms, a new class of merchants, landlords and craftsmen was forming — the class widely known in Europe by its French name, the bourgeoisie. Inevitably, as this new class gained strength, it chafed against the many confines of feudal society. As in Europe, the king (Emperor) became the central figure in the bourgeoisie's struggle for power against the feudal aristocracy. But a political leadership does not always fully understand the interests of the class it serves. When the outside world arrived with a bang in 1853, in the form of U.S. Admiral Perry's "Black Ships," the ruling elite of Japan were thrown into a crisis. Their military was no match for these foreigners. Also, they had heard about the havoc the British and French imperialists were wreaking in China. What should Japan do to save itself from the fate of its weak neighbor? Surprisingly, some elements within the usually isolationist Shogunate were inclined to open trade with the foreigners in order to obtain some of their advanced technology. This is the point of view represented (just barely) in the film by Sakamoto. On the other hand, the Emperor-loyal ultra-nationalists, represented by Takechi, believed they could keep out the foreigners by force, if only they could prevent the other faction from "selling out the country." (Sound familiar?) Thus, the assassination of key Shogunate figures is in order — and away we go.

Takechi's motivations were, for me, the film's biggest puzzle. Gosha suggests that he is fighting mainly for his personal advancement rather than for the Loyalist cause. Can we take this to represent the tenor of the Loyalists as a whole? (Do you care?)

Several reviewers compared this film favorably with "Goyokin," which Gosha made in the same year. But, where "Goyokin" is a crackling, suspenseful, adventure yarn, with a hero worthy of sympathy, "Hitokiri" is plodding, nowhere near as compelling and lacks such a hero. Sakamoto could have been this film's hero but we are not allowed to know him — nor what he stands for — well enough for him to achieve that status.

In view of his wonderful scores for five previous Kurosawa films, Masaru Sato's score here was very disappointing, sounding like something rejected from a "Bonanza" episode.

Barry Freed

Gosha's last great film of the 1960's. A resolute stylist with a great sense of purpose to his films, Gosha teamed up with Shintaro Katsu (of Zatoichi fame) to produce this scathing indictment of mindless nationalist loyalty.

"Tenchu" (heavenly judgment) is the word that the loyalists to the emperor yell while assassinating enemies or "traitors" to the cause. Katsu plays up his character' simple minded allegiance to a manipulative politician all in the name of patriotic pride. Anybody who questions the politician is labeled a "traitor" and becomes an assassination target.

One of the best photographed films ever, many shots are incredible compositions of form, color and light. The fight scenes are frequent and very bloody and brutal. The blood becomes a part of the color palette Gosha uses for his images. Gorgeous and disturbing. While the personal story is simple to follow, the historical background is complicated and while a basic history lesson for this time in Japan would be very helpful you can struggle through the film without it. The few drawbacks to the film are the music track, the length and Katsu's occasional scenery chewing. He has a drunken scene that's way over the top for a film but actually a very accurate depiction of a drunk.

Downbeat but one of the great chambara films.

"Tenchu" (heavenly judgment) is the word that the loyalists to the emperor yell while assassinating enemies or "traitors" to the cause. Katsu plays up his character' simple minded allegiance to a manipulative politician all in the name of patriotic pride. Anybody who questions the politician is labeled a "traitor" and becomes an assassination target.

One of the best photographed films ever, many shots are incredible compositions of form, color and light. The fight scenes are frequent and very bloody and brutal. The blood becomes a part of the color palette Gosha uses for his images. Gorgeous and disturbing. While the personal story is simple to follow, the historical background is complicated and while a basic history lesson for this time in Japan would be very helpful you can struggle through the film without it. The few drawbacks to the film are the music track, the length and Katsu's occasional scenery chewing. He has a drunken scene that's way over the top for a film but actually a very accurate depiction of a drunk.

Downbeat but one of the great chambara films.

Did you know

- TriviaYukio Mishima's character commits seppuku and one year later, Mishima himself will commit the same way of ritual suicide.

- ConnectionsVersion of Izo (2004)

- How long is Hitokiri?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Runtime2 hours 20 minutes

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 2.35 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content