IMDb RATING

7.2/10

5K

YOUR RATING

A TV news reporter finds himself becoming personally involved in the violence that erupts around the 1968 Democratic National Convention.A TV news reporter finds himself becoming personally involved in the violence that erupts around the 1968 Democratic National Convention.A TV news reporter finds himself becoming personally involved in the violence that erupts around the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

- Awards

- 2 wins & 4 nominations total

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

Movies have a way of capturing the moment better than recreating it. I can only dread what a recreated 1968 in Chicago would look like from a Hollywood perspective. It would probably resemble something out of Forrest Gump. But Medium Cool happened to capture some brutal fight scenes with police in Chicago as well as scenes from the black ghettos. You can't recreate this stuff. This isn't a documentary but cinema verité and combines fiction and non-fictional elements. It's all shot with Chicago of 68 in the background. A landmark and infamous year for the US with the assassinations of RFK and MLK as well as the 1968 Democratic National Convention which was met with severe state repression. The state wasn't negotiating at this time, it was brutally sending men off to war and attacking those at home with the hired goons of the police force.

It's a great movie which manages to combine fiction and non-fiction and shows us what the sixties were really like. It wasn't all love beads and LSD, although there is an amusing psychedelic sequence which takes place in a club.

I think what I liked most was that even people who were non-political were being dragged into the politics of the time. Events were that serious at the time and people had to begin picking sides, the pleasant, white, middle-class interior of the Chicago DNC or outside fighting and raging against the police.

It's a great movie which manages to combine fiction and non-fiction and shows us what the sixties were really like. It wasn't all love beads and LSD, although there is an amusing psychedelic sequence which takes place in a club.

I think what I liked most was that even people who were non-political were being dragged into the politics of the time. Events were that serious at the time and people had to begin picking sides, the pleasant, white, middle-class interior of the Chicago DNC or outside fighting and raging against the police.

10jzappa

One of the most truthful moments I've seen in a film in a long time: We hear MLK speaking on TV, a professional cameraman watching. We hear King's immortal words which have resounded through the decades, and when Forster finally speaks, he says, "God, I love shooting on film." Medium Cool is full of moments like this, where we see or hear something that plugs into what we're truly thinking, disconcertingly enough, at times when what we're thinking seems to obviously be something else. In Medium Cool, we respond to these things and, some forty years later, aren't quite sure what's real and what's not. This most head-on and seemingly makeshift of films was released in 1969 to reaction and surmise. Five years before, it would have been deemed unintelligible to the general movie audience. What happened, I suppose, is that by then we'd become so trained by the quick-cutting, idea suggestion and stream of consciousness of concepts in TV commercials that we process more quickly than feature-length movies can move. We get cinematic fast-sketch. And we like movies that recognize our intelligence.

Traditional film narratives pronounce themselves: We know all the main techniques/content and archetypal characters. Haskell Wexler's Medium Cool is one of several movies of the late 1960s and '70s that's conscious of these things about movie audiences, like Seconds, Easy Rider, Mean Streets, Who's That Knocking At My Door, The Graduate, The French Connection, etc. Of the bunch, Medium Cool is probably the most visceral. That may be since Wexler, for most of his career, has been a cinematographer, and so he's conditioned to see a movie pertaining to what's being shown and not shown on-screen more than its dialogue and story.

Wexler fabricates a fictional story about the TV cameraman, his passion, his profession, his girl and her son. There is also documentary footage about the riots during the Democratic convention. There is a chain of conscious scenarios that supposes reality (women taking marksmanship practice, the TV crew confronting black militants). There are fictitious characters in actual documentary scenes and vice versa. The misstep would be to segregate the real-life elements from the made-up. They're all equally meaningful. The National Guard troops are no more real than the love scene, or the artificial collision that ends the film. All the images have significance due to the way they are connected to each other.

Wexler induces our recollection of the zillions of other movies we've seen to import things about his plot that he never elucidates on screen. The essential account of the romance (young professional falls in love with war-widow, eventually obtains companionship of her resentful son) is surely not innovative. If Wexler had formalized it, it would have been commonplace and dull. Rather, he specializes in the emblematic and important features of this histrionic (the boy likes pigeons, the woman is a teacher, the location is Uptown, the time is the Democratic convention, the woman feels more authentic to the cameraman than the model he's living with). And these are the scenes Wexler shoots. The leftovers of the relationship are implicit and never shown, eschewing the often essentially unnecessary 2 on our way from 1 to 3.

And Medium Cool also sees not images but their purpose: Wexler doesn't see the hippie kids in Grant Park as hippie kids. He doesn't see the clothes or the folkways, and he doesn't hear the words. He distinguishes their purpose; they are there completely owing to the National Guard being there, and the opposite. Both sides have a purpose just when they encounter one another. Without the encounter, all you'd have would be the kids, dispersed all over the country, and the guardsmen, dressed in civilian clothes and spending the week on their daily grinds. That's interesting too, but it's not what they are that's significant in this film; it's what they're doing there.

Medium Cool is ultimately so seminal, and engaging, owing to the way Wexler braids all these components together. He has made a nearly consummate model of the movie of its time. Since we are so conscious this is a movie, it feels more pertinent and authentic than the graceful fictitious artifice of most other films, including better ones. This befits the last scene all by itself, that chance event that occurs for no reason at all. Chance events are invariably chance events, not fate, not God's will, not karma, and they never occur for a greater purpose. When we get it, it hit me that it's the first movie collision I've ever seen that we weren't anticipating for five minutes before.

Traditional film narratives pronounce themselves: We know all the main techniques/content and archetypal characters. Haskell Wexler's Medium Cool is one of several movies of the late 1960s and '70s that's conscious of these things about movie audiences, like Seconds, Easy Rider, Mean Streets, Who's That Knocking At My Door, The Graduate, The French Connection, etc. Of the bunch, Medium Cool is probably the most visceral. That may be since Wexler, for most of his career, has been a cinematographer, and so he's conditioned to see a movie pertaining to what's being shown and not shown on-screen more than its dialogue and story.

Wexler fabricates a fictional story about the TV cameraman, his passion, his profession, his girl and her son. There is also documentary footage about the riots during the Democratic convention. There is a chain of conscious scenarios that supposes reality (women taking marksmanship practice, the TV crew confronting black militants). There are fictitious characters in actual documentary scenes and vice versa. The misstep would be to segregate the real-life elements from the made-up. They're all equally meaningful. The National Guard troops are no more real than the love scene, or the artificial collision that ends the film. All the images have significance due to the way they are connected to each other.

Wexler induces our recollection of the zillions of other movies we've seen to import things about his plot that he never elucidates on screen. The essential account of the romance (young professional falls in love with war-widow, eventually obtains companionship of her resentful son) is surely not innovative. If Wexler had formalized it, it would have been commonplace and dull. Rather, he specializes in the emblematic and important features of this histrionic (the boy likes pigeons, the woman is a teacher, the location is Uptown, the time is the Democratic convention, the woman feels more authentic to the cameraman than the model he's living with). And these are the scenes Wexler shoots. The leftovers of the relationship are implicit and never shown, eschewing the often essentially unnecessary 2 on our way from 1 to 3.

And Medium Cool also sees not images but their purpose: Wexler doesn't see the hippie kids in Grant Park as hippie kids. He doesn't see the clothes or the folkways, and he doesn't hear the words. He distinguishes their purpose; they are there completely owing to the National Guard being there, and the opposite. Both sides have a purpose just when they encounter one another. Without the encounter, all you'd have would be the kids, dispersed all over the country, and the guardsmen, dressed in civilian clothes and spending the week on their daily grinds. That's interesting too, but it's not what they are that's significant in this film; it's what they're doing there.

Medium Cool is ultimately so seminal, and engaging, owing to the way Wexler braids all these components together. He has made a nearly consummate model of the movie of its time. Since we are so conscious this is a movie, it feels more pertinent and authentic than the graceful fictitious artifice of most other films, including better ones. This befits the last scene all by itself, that chance event that occurs for no reason at all. Chance events are invariably chance events, not fate, not God's will, not karma, and they never occur for a greater purpose. When we get it, it hit me that it's the first movie collision I've ever seen that we weren't anticipating for five minutes before.

This film is better upon the second viewing, the first time I saw this I thought it was somewhat dated or boring, I couldn't have been more wrong. Initially I watched this film because it was directed by Haskell Wexler whose work I admire, and I'm from Chicago and had heard it shows much of the city and the riots of 68. I enjoyed seeing the city forty years ago to see what was the same and what had changed, much has changed yet much remains the same from what I have seen of the people, places, buildings etc. It was great to see the Kinetic Playground on there, Chicago's electric ballroom, and other area's such as Lincoln Park. On the second viewing, I realized that this is a very important film in that it adroitly captures a moment in time, a moment we can never have again that is lost forever, that one second in our history that pivoted us as a nation between innocence and awareness and possibly that crucial moment which has brought us to the point we are at today. This movie is very important as a document of history, not to mention how well it's shot. The angles, the color, the way he goes in and out of focus make this a true gem that gets better the more you see it. Great soundtrack as well, Zappa, Mike Bloomfield and others.

This film is a mixture of documentary footage and conventional narrative.

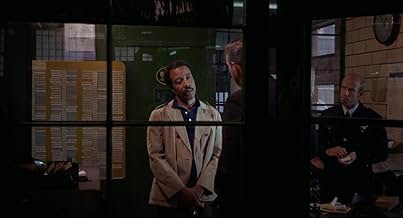

It tells the story of a tough news camera-man (Robert Forster) who falls for a young widow (Verna Bloom) and befriends her thirteen-year-old son, against the back-drop of the riots in Chicago in 1968.

The film utilises both professional actors and non-professionals, to very good effect. In fact there are scenes, such as the riot sequences, where there is a genuine sense of danger.

The main flaw in the film is that the love story is not well-handled and often quite dull, the far more interesting events are happening elsewhere.

This is a deeply political work and is savagely critical of the callous and cynical media, which distorts people's perceptions of the world.

Worth watching for anyone interested in the sixties, political cinema or American independent film.

Great soundtrack too.

It tells the story of a tough news camera-man (Robert Forster) who falls for a young widow (Verna Bloom) and befriends her thirteen-year-old son, against the back-drop of the riots in Chicago in 1968.

The film utilises both professional actors and non-professionals, to very good effect. In fact there are scenes, such as the riot sequences, where there is a genuine sense of danger.

The main flaw in the film is that the love story is not well-handled and often quite dull, the far more interesting events are happening elsewhere.

This is a deeply political work and is savagely critical of the callous and cynical media, which distorts people's perceptions of the world.

Worth watching for anyone interested in the sixties, political cinema or American independent film.

Great soundtrack too.

A rare directorial outing by all-time great cinematographer Wexler, this is generally acknowledged as the most politically radical film ever produced by a major studio. In freewheeling, semi-improvised, ideologically calculated scene after scene, it depicts an apolitical television cameraman's awakening of consciousness and abandonment of the role of passive observer. The class and race politics are four notches up on any comparable contemporary studio feature, that's for sure - with the surprisingly patient explanation of how 6-o-clock-news ideology oppresses minority communities, leading in to a love affair with a working-class single mother instead of some vanguard hippie, you could even argue that this Americanization of Godard has better ideological legs than the master himself. Sure it meanders a tad, and the stylistics can date, but there's nothing else in any movie ever that compares with the climax, as the actors make their way through actual documentary footage of the 1968 Democratic convention and attendant street battles. I mean, how did such a finely balanced mix of integrated narrative, Euro-tics, American underground film and straight-up documentary even occur to them? And how did they then manage to actually pull it off with honors? Pretty damned impressive.

Did you know

- TriviaThe line "Look out, Haskell, it's real!" was actually dubbed in after the shooting. It was supposedly what Haskell Wexler was thinking to himself and he wanted to include it.

- GoofsWhen Eileen enters the L looks for Harold, she is wearing a white hair band, but when they show her sitting on the L, the hair band is missing.

- Quotes

John Cassellis: If I gotta be afraid in order for your argument to work, then you got no argument.

- Crazy creditsStuds Terkel is credited as "Our Man in Chicago".

- Alternate versionsDue to copyright disputes, all video releases feature some different songs on the soundtrack from the theatrical version.

- ConnectionsEdited into The Kid Stays in the Picture (2002)

- SoundtracksSweet Georgia Brown

by Ben Bernie, Kenneth Casey and Maceo Pinkard

Performed by Brother Bones

Courtesy of Tempo Records

Played during roller derby scene

- How long is Medium Cool?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box office

- Budget

- $800,000 (estimated)

- Runtime

- 1h 51m(111 min)

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.85 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content