IMDb RATING

6.3/10

700

YOUR RATING

In Weimar-era Berlin, an aspiring writer strikes up a friendship with a vivacious, penniless singer.In Weimar-era Berlin, an aspiring writer strikes up a friendship with a vivacious, penniless singer.In Weimar-era Berlin, an aspiring writer strikes up a friendship with a vivacious, penniless singer.

- Director

- Writers

- Stars

- Nominated for 1 BAFTA Award

- 1 nomination total

William Adams

- Old Doctor

- (uncredited)

Ian Ainsley

- Minor Role

- (uncredited)

Charles Andre

- Waiter

- (uncredited)

Julia Arnall

- Model

- (uncredited)

Jack Arrow

- Troika Doorman

- (uncredited)

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

Sally Bowles, the glittering, swaggering, sexually adventurous nightclub chanteuse at the centre of Cabaret is one of the most memorable figures in 70s cinema. Liza Minnelli, who played her in Bob Fosse's critically acclaimed 1972 musical, won an Oscar in the part that seemed tailor-made for her — from the black bowler hat to those kinky boots.

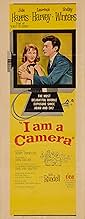

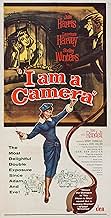

It may be hard to believe now, but in the mid-50s, Julie Harris was Sally Bowles. She played her on stage in John Van Druten's play I Am a Camera — winning a Tony award — and reprised the role in Henry Cornelius's 1955 film. Both works were based on Christopher Isherwood's The Berlin Stories, but their portrayals of Berlin in the early 30s could scarcely be more different. To appreciate Harris's take on Sally you really have to banish memories of the Kit Kat Club, Joel Grey's louche MC and those fabulous songs.

"The more worthless the book the more they need noise and alcohol to launch it." Middle-aged writer Christopher Isherwood (Laurence Harvey) begins this semi-autobiographical tale of his youthful adventures in pre-Second World War Germany with the discovery that sex sells. The irrepressible Sally Bowles has turned author, with the provocatively entitled The Lady Goes on Hoping. Some things never change.

After this Bloomsbury-set opening sequence, I Am a Camera flashes back to Berlin on New Year's Eve 1931. Isherwood, narrates the story of his life as a struggling author, living in a boarding house run by the long-suffering Fräulein Schneider. So far, it seems that his one moment of inspiration has been to come up with that title: "I am a camera, with its shutter open, just watching it, quite detached." Isherwood's professional detachment is tested when he accompanies his friend Fritz (Anton Diffring) to a club, where Sally is performing. In what we soon learn is a familiar pattern, she is soon left high a dry by her latest beau. Feeling sorry for this "naive" girl, our hero gallantly offers her a room for the night, though the platonic terms of their relationship are made clear from the outset.

It's not long before the totally out-of-his depth novelist realises that his new friend's modus operandi is to shock people. Asked why she wears green nail polish, Sally cheerfully explains "To attract men!" As their life together descends into penury and bickering, he alternates between fascination at Sally's lack of morals and self-pity at his inability to make progress with his work.

Harvey went on to play the social-climbing Joe Lampton in Room at the Top and the brainwashed assassin Raymond Shaw in The Manchurian Candidate. I find him more convincing as an embittered cynic than as a suave leading man, so he's well-suited to the role of the permanently exasperated Isherwood. When his one clumsy attempt to seduce Sally is repelled, his sardonic response is to ask "A puritan all of a sudden, or just where I'm concerned?" With her throaty laugh, theatrical mannerisms and fine comedic timing, Harris's Sally is an enthralling and infuriating companion. In the film's most enjoyable sequences, she drags the hard-up Isherwood into a bar, where she downs a succession of champagne cocktails. The arrival of filthy rich American Clive (Ron Randell) leads to a wild party — complete with a hydro-therapist played by Patrick McGoohan.

Of course the sexual dynamics would have looked very different if this film hadn't been made in the mid-50s. There's no hint here that the writer might be gay, or even bisexual – as Michael York's Brian is in Cabaret. Instead, the would-be novelist is just celibate, waspish and openly disapproving of Sally's promiscuity. In the film of Isherwood's later novel, A Single Man, George (Colin Firth) and his best friend Charley (Julianne Moore) have once been on intimate terms, but she reluctantly has to accept his homosexuality.

John Collier's screenplay is at its sharpest and most assured in the scenes of domestic cut and thrust between the flat-mates. But attempts to bring the social and political unrest of pre-war Berlin into the mix are less successful. Though Berlin was on the cusp of seismic events you get little sense here of the growing unease on the streets, while the nightclub scenes are more dreary than decadent. There is an awkward romantic subplot involving Fritz and the wealthy Natalia (a miscast Shelley Winters) that tries to address the dilemma facing Jewish citizens. Isherwood makes a belated attempt to reclaim his independence by brawling with some Nazis in the street, and rebukes Fräulein Schneider for an anti-Semitic remark.

Cornelius, who directed only five films, had to work within the censorship restrictions of the time. This movie may have been an X-certificate in its day, but the Sally of 1955 doesn't get to be as wanton — or show as much leg — as the Sally of Cabaret. As a portrait of the artist as a young man, I Am a Camera is funny and charming and the two leads have good chemistry. But if you want to know why money still makes the world go round, the Kit Kat Club is the place to go.

It may be hard to believe now, but in the mid-50s, Julie Harris was Sally Bowles. She played her on stage in John Van Druten's play I Am a Camera — winning a Tony award — and reprised the role in Henry Cornelius's 1955 film. Both works were based on Christopher Isherwood's The Berlin Stories, but their portrayals of Berlin in the early 30s could scarcely be more different. To appreciate Harris's take on Sally you really have to banish memories of the Kit Kat Club, Joel Grey's louche MC and those fabulous songs.

"The more worthless the book the more they need noise and alcohol to launch it." Middle-aged writer Christopher Isherwood (Laurence Harvey) begins this semi-autobiographical tale of his youthful adventures in pre-Second World War Germany with the discovery that sex sells. The irrepressible Sally Bowles has turned author, with the provocatively entitled The Lady Goes on Hoping. Some things never change.

After this Bloomsbury-set opening sequence, I Am a Camera flashes back to Berlin on New Year's Eve 1931. Isherwood, narrates the story of his life as a struggling author, living in a boarding house run by the long-suffering Fräulein Schneider. So far, it seems that his one moment of inspiration has been to come up with that title: "I am a camera, with its shutter open, just watching it, quite detached." Isherwood's professional detachment is tested when he accompanies his friend Fritz (Anton Diffring) to a club, where Sally is performing. In what we soon learn is a familiar pattern, she is soon left high a dry by her latest beau. Feeling sorry for this "naive" girl, our hero gallantly offers her a room for the night, though the platonic terms of their relationship are made clear from the outset.

It's not long before the totally out-of-his depth novelist realises that his new friend's modus operandi is to shock people. Asked why she wears green nail polish, Sally cheerfully explains "To attract men!" As their life together descends into penury and bickering, he alternates between fascination at Sally's lack of morals and self-pity at his inability to make progress with his work.

Harvey went on to play the social-climbing Joe Lampton in Room at the Top and the brainwashed assassin Raymond Shaw in The Manchurian Candidate. I find him more convincing as an embittered cynic than as a suave leading man, so he's well-suited to the role of the permanently exasperated Isherwood. When his one clumsy attempt to seduce Sally is repelled, his sardonic response is to ask "A puritan all of a sudden, or just where I'm concerned?" With her throaty laugh, theatrical mannerisms and fine comedic timing, Harris's Sally is an enthralling and infuriating companion. In the film's most enjoyable sequences, she drags the hard-up Isherwood into a bar, where she downs a succession of champagne cocktails. The arrival of filthy rich American Clive (Ron Randell) leads to a wild party — complete with a hydro-therapist played by Patrick McGoohan.

Of course the sexual dynamics would have looked very different if this film hadn't been made in the mid-50s. There's no hint here that the writer might be gay, or even bisexual – as Michael York's Brian is in Cabaret. Instead, the would-be novelist is just celibate, waspish and openly disapproving of Sally's promiscuity. In the film of Isherwood's later novel, A Single Man, George (Colin Firth) and his best friend Charley (Julianne Moore) have once been on intimate terms, but she reluctantly has to accept his homosexuality.

John Collier's screenplay is at its sharpest and most assured in the scenes of domestic cut and thrust between the flat-mates. But attempts to bring the social and political unrest of pre-war Berlin into the mix are less successful. Though Berlin was on the cusp of seismic events you get little sense here of the growing unease on the streets, while the nightclub scenes are more dreary than decadent. There is an awkward romantic subplot involving Fritz and the wealthy Natalia (a miscast Shelley Winters) that tries to address the dilemma facing Jewish citizens. Isherwood makes a belated attempt to reclaim his independence by brawling with some Nazis in the street, and rebukes Fräulein Schneider for an anti-Semitic remark.

Cornelius, who directed only five films, had to work within the censorship restrictions of the time. This movie may have been an X-certificate in its day, but the Sally of 1955 doesn't get to be as wanton — or show as much leg — as the Sally of Cabaret. As a portrait of the artist as a young man, I Am a Camera is funny and charming and the two leads have good chemistry. But if you want to know why money still makes the world go round, the Kit Kat Club is the place to go.

In this film Julie Harris reprises her Tony award-winning performance as Sally Bowles bumming in 1920s Berlin. I loved Julie and envied Sally and her carefree ways, but I was young then. While the film may not be "important," it does tell us something about life and culture based upon Christopher Isherwood's evocation of fun-loving pre-Hitler Berlin. It's about a world and time long vanished & highly lamented by aging romantics such as I. So temper your critical faculties and just enjoy a stunning performance by Julie Harris who has won more Tony Awards (5) than any other actress.

Unfortunately for Henry Cornelius's "I am a Camera" and its delightful star, Julie Harris, that film will forever lie in the shadow of Bob Fosse's Oscar-winning musical, "Cabaret." This 1955 film, the 1972 Fosse musical, the original 1951 stage play, and the 1966 Kander and Ebb Broadway musical were all based on stories by Christopher Isherwood; the tales relate the writer's time spent in Berlin during the early 1930's, where he met and enjoyed a platonic relationship with the irrepressible Sally Bowles, a cabaret singer and aspiring film star. Bookended by Isherwood in voice-over recalling Bowles and Berlin to colleagues at a reception for the publication of Bowles's memoirs, "I am a Camera" is a highly enjoyable movie that has unjustly been eclipsed by the subsequent musical version.

Comparisons between the two movie versions are inescapable. "I am a Camera" was filmed late in period when the Motion Picture Production Code and the Legion of Decency ruled Hollywood; any mention of homosexuality, bisexuality, promiscuity, or abortion were forbidden, and those subjects are only alluded to with veiled references. However, by the time Fosse filmed the musical remake, the Code and the Legion were history, and, in "Cabaret," Christopher openly liked boys, Sally had an abortion, and Sally's straight boyfriend, Clive, in the earlier film, had become the bisexual Maximilian von Heune, who bedded both Sally and Chris. Although the rise of the Nazis and anti-Semitism were depicted in both films, "Cabaret" hit the subject with more force.

Julie Harris created Sally Bowles on stage, and her performance in "I am a Camera" is wonderful; she is alternately touching, exasperating, thoughtless, endearing, and always flamboyant as a nightclub singer of lesser talent, who dreams of big things, but always chooses the wrong men in her pursuit of the good life. Laurence Harvey is quite good in the less showy role of Chris; his overlong pouffed hair, prudishness, and indifference to Harris's physical charms wordlessly suggest his sexual orientation. Anton Diffring and Shelley Winters are also effective as the Jewish lovers, Fritz and Natalia, who cautiously court, while the threat of Naziism swirls around them. Ron Randell is also fine as Clive, Sally's wealthy party-loving beau.

Although short and censored, "I am a Camera" is possibly truer to Isherwood's stories and the real Sally than was "Cabaret." Based on a play by John van Druten, John Collier adapted and likely sanitized Isherwood for the screen. Shot in black and white by Guy Green, the film retains some staginess, but maintains a decent pace. However, most importantly, "I am a Camera" preserves the Julie Harris performance that created the unforgettable Sally Bowles.

Comparisons between the two movie versions are inescapable. "I am a Camera" was filmed late in period when the Motion Picture Production Code and the Legion of Decency ruled Hollywood; any mention of homosexuality, bisexuality, promiscuity, or abortion were forbidden, and those subjects are only alluded to with veiled references. However, by the time Fosse filmed the musical remake, the Code and the Legion were history, and, in "Cabaret," Christopher openly liked boys, Sally had an abortion, and Sally's straight boyfriend, Clive, in the earlier film, had become the bisexual Maximilian von Heune, who bedded both Sally and Chris. Although the rise of the Nazis and anti-Semitism were depicted in both films, "Cabaret" hit the subject with more force.

Julie Harris created Sally Bowles on stage, and her performance in "I am a Camera" is wonderful; she is alternately touching, exasperating, thoughtless, endearing, and always flamboyant as a nightclub singer of lesser talent, who dreams of big things, but always chooses the wrong men in her pursuit of the good life. Laurence Harvey is quite good in the less showy role of Chris; his overlong pouffed hair, prudishness, and indifference to Harris's physical charms wordlessly suggest his sexual orientation. Anton Diffring and Shelley Winters are also effective as the Jewish lovers, Fritz and Natalia, who cautiously court, while the threat of Naziism swirls around them. Ron Randell is also fine as Clive, Sally's wealthy party-loving beau.

Although short and censored, "I am a Camera" is possibly truer to Isherwood's stories and the real Sally than was "Cabaret." Based on a play by John van Druten, John Collier adapted and likely sanitized Isherwood for the screen. Shot in black and white by Guy Green, the film retains some staginess, but maintains a decent pace. However, most importantly, "I am a Camera" preserves the Julie Harris performance that created the unforgettable Sally Bowles.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing. Much reviled when it first appeared, (inspiring the famous review 'Me No Leica'), this precursor of "Cabaret" can now be looked at in comparison and it's not half bad. It's certainly no classic but it has its own wayward charm, (the film version of "Cabaret" follows this plot whereas the stage version changed the plot somewhat). One should, of course, resist the temptation to snicker when Laurence Harvey's Christopher Isherwood, (it keeps the original author's real name; God Knows what Isherwood thought of it), describes himself as 'a confirmed bachelor' and while Harvey is an utterly inadequate 'hero', (he's virtually asexual), and Shelly Winters woefully miscast as Fraulien Landauer, (the part Marisa Berenson played in "Cabaret"), Julie Harris is a perfectly marvellous Sally, (it's a lovely piece of comic acting), and Anton Diffring is first-rate as Fritz, the German-Jew in love with Shelly's character. Of course, if "Cabaret" had never come along you might ask yourself would this ever have seen the light of day again. That it has been revived may not quite be cause for celebration but it's perfectly acceptable all the same.

This film was inexplicably made in England, and though there is some staginess - noticably in the yelling of some of the actors - director Henry Cornelius provides some clever imagery eg the decadence of the Berlin nightclub by a piglet and two smashing beerglasses, and Christopher standing at a window in the past bringing out us out of the narrative flashback. It also features a remarkable hotel party setpiece.

The infamous role of Sally Bowles is written as a pretentious innocent, and the knowledge that Isherwood was gay feeds into the notion of Sally as a coded drag queen, or at least, an effeminate gay man. The screenplay is full of gay subtext eg Christopher's narcissism demonstrated in his lotions and weights and boufant hairstyle, Sally's descriptions of male musculature, the repeated use of sausages, Sally telling Christopher he doesn't "understand" women, his describing her sex appeal as "inadequate", the rectal thermometer, his massage, his confession that he is "not the marrying type", and fear of being "embroiled" with her. The major difference between this treatment and that of Bob Fosse's Cabaret is the Clive Mortimer character, who here is heterosexual, but would be later turned into the bisexual Max.

Julie Harris performed the role of Sally Bowles on Broadway, and one's opinion of her performance cannot help but be influenced by Liza Minnelli (as is one's opinion of the film as a piece). Harris works against her basic miscasting (she doesn't even use an English accent when we are told Sally is English) because Sally is such an artificial creation. She is like an Actors Studio version of a junior Auntie Mame, and even when her antics become tiresome, she is still far more likeable than Laurence Harvey's starched and basically asexual Christopher. Harris may not have Minnelli's street urchin vulnerability, but she has some inspired moments - posing in front of a mirror wearing a mink coat, her drunken giggling, looking behind a silk scarf, or licking milk with a wild tongue.

The infamous role of Sally Bowles is written as a pretentious innocent, and the knowledge that Isherwood was gay feeds into the notion of Sally as a coded drag queen, or at least, an effeminate gay man. The screenplay is full of gay subtext eg Christopher's narcissism demonstrated in his lotions and weights and boufant hairstyle, Sally's descriptions of male musculature, the repeated use of sausages, Sally telling Christopher he doesn't "understand" women, his describing her sex appeal as "inadequate", the rectal thermometer, his massage, his confession that he is "not the marrying type", and fear of being "embroiled" with her. The major difference between this treatment and that of Bob Fosse's Cabaret is the Clive Mortimer character, who here is heterosexual, but would be later turned into the bisexual Max.

Julie Harris performed the role of Sally Bowles on Broadway, and one's opinion of her performance cannot help but be influenced by Liza Minnelli (as is one's opinion of the film as a piece). Harris works against her basic miscasting (she doesn't even use an English accent when we are told Sally is English) because Sally is such an artificial creation. She is like an Actors Studio version of a junior Auntie Mame, and even when her antics become tiresome, she is still far more likeable than Laurence Harvey's starched and basically asexual Christopher. Harris may not have Minnelli's street urchin vulnerability, but she has some inspired moments - posing in front of a mirror wearing a mink coat, her drunken giggling, looking behind a silk scarf, or licking milk with a wild tongue.

Did you know

- TriviaDespite being far less salacious than the 1951 stage play on which it was based, this film adaptation received a "Condemned" rating from the Legion of Decency, a Roman Catholic organization that passed moral judgments on films between 1933 and 1965. This rating was also given to Psychose (1960), Certains l'aiment chaud (1959) and À bout de souffle (1960).

- GoofsWhilst most of the film is a flashback set in the early 1930s, all the costumes and hairstyles worn are straight out of the early 1950s.

- Quotes

Christopher Isherwood: [to Sally] Any mess you get into, you try and get out of by using your extremely inadequate sex appeal.

- Crazy creditsIn opening credits, Shelley Winters is misspelled "Shelly".

- ConnectionsFeatured in Omnibus: Christopher Isherwood: A Born Foreigner (1969)

- SoundtracksI Saw Him in a Café in Berlin

(uncredited)

Music by Ralph Maria Siegel

English lyrics by Paul Dehn

Sung by Liselotte Malkowsky

[Sally (Julie Harris) sings the song in her club act]

- How long is I Am a Camera?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Runtime1 hour 38 minutes

- Color

- Aspect ratio

- 1.37 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content