IMDb RATING

7.2/10

2.1K

YOUR RATING

A politically ambitious district attorney, unscrupulous tabloid journalists, and regional prejudice combine to charge a teacher with the murder of his student.A politically ambitious district attorney, unscrupulous tabloid journalists, and regional prejudice combine to charge a teacher with the murder of his student.A politically ambitious district attorney, unscrupulous tabloid journalists, and regional prejudice combine to charge a teacher with the murder of his student.

- Director

- Writers

- Stars

- Awards

- 3 wins total

Elisabeth Risdon

- Mrs. Hale

- (as Elizabeth Risdon)

Sibyl Harris

- Mrs. Clay

- (as Sybil Harris)

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

This may well be the most depressing movie ever made. Based on a notorious murder case, the audience is spared nothing. I think it took guts for producer Mervyn Leroy to make this film. Many theaters refused to show it. The role of a lifetime for actor Claude Rains, I was impressed by the performance of the actress who plays the wife of the victim of a trial that never should have been. It takes a strong stomach to sit through until the end. The film did win awards, but the Academy of Arts and Sciences was afraid to touch it. In real life the victim of the miscarriage of justice was exonerated many years later, but the political career of the Governor who tried to commute his sentence was ruined.

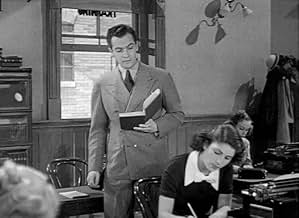

Mary Clay, played by Lana Turner (living up to her sweater girl fame) very early in her career is a student at a small southern town's business college. She has a crush on her teacher, Professor Robert Hale, played by Edwin Norris. Hale, is a man from the north - not really welcomed in a town that has a parade for Confederate Memorial Day. After the class was dismissed, Mary and a friend went for a soda and Mary forgot her vanity case. She went back to the school and was murdered.

Local newspaper staff bursts into Hale's apartment, tells Hale's wife that he's in jail, and after she faints, newsmen search the apartment, taking a honeymoon photo, searching through drawers.

This movie demonstrates how a quest for political power can taint a trial. Being an "outsider" can make it difficult for a fair trial. Although this takes place in the south, mob justice can and has occurred all over the country during the 1920's and 1930's.

Local newspaper staff bursts into Hale's apartment, tells Hale's wife that he's in jail, and after she faints, newsmen search the apartment, taking a honeymoon photo, searching through drawers.

This movie demonstrates how a quest for political power can taint a trial. Being an "outsider" can make it difficult for a fair trial. Although this takes place in the south, mob justice can and has occurred all over the country during the 1920's and 1930's.

"They Won't Forget" and neither will you if you've seen this chilling depression-era drama based on an actual murder case. Some of the scenes are so real, they're scary. One look at gimlet-eyed Trevor Bardette with a voice from the grave is like seeing death incarnate and enough to freeze a platoon of marines in their tracks. Then there's hapless Clinton Rosemon, his pleas for mercy so achingly real, they echo across generations of tormented black souls. Also not to be overlooked is the bereaved Gloria Dickson. Her righteous anger at movie's end is so heart-felt, I expect it probably was. Together with the wily District Attorney Claude Rains, there's an uncommon authority to this searing drama of justice gone wrong.

There's also an uncommon richness of detail. The script, for all its sprawl, remains tight and unrelenting, a genuine testament to writers Rossen and Kandel. Then too, producer Le Roy pulled out all the stops and the results show it. No one acts without apparent reason. Everyone has understandable motivations for doing what they do. That's why the upshot is so tragic. It's as though there's an on-rushing train nobody can stop because the momentum is carried by an infernal logic greater than the demands of justice. Despite appearances, it's not an anti-lynching film, though it is that. Rather, it's a down and dirty look at the cynical roots of injustice. From lowly pool hall to lofty city council, no one wants to convict an innocent man, but then no one much cares either. This movie stands as a fine example of why Warner Bros. was the studio of record during the stressed-out 1930's. Anyway, for guys who don't like the gloomy theme, there's always the chance to catch Lana Turner as she juggles two balloons while sashaying up the sidewalk in the film's most famous scene.

All in all-- a classic of 30's social realism, with Hollywood at its unapologetic best.

There's also an uncommon richness of detail. The script, for all its sprawl, remains tight and unrelenting, a genuine testament to writers Rossen and Kandel. Then too, producer Le Roy pulled out all the stops and the results show it. No one acts without apparent reason. Everyone has understandable motivations for doing what they do. That's why the upshot is so tragic. It's as though there's an on-rushing train nobody can stop because the momentum is carried by an infernal logic greater than the demands of justice. Despite appearances, it's not an anti-lynching film, though it is that. Rather, it's a down and dirty look at the cynical roots of injustice. From lowly pool hall to lofty city council, no one wants to convict an innocent man, but then no one much cares either. This movie stands as a fine example of why Warner Bros. was the studio of record during the stressed-out 1930's. Anyway, for guys who don't like the gloomy theme, there's always the chance to catch Lana Turner as she juggles two balloons while sashaying up the sidewalk in the film's most famous scene.

All in all-- a classic of 30's social realism, with Hollywood at its unapologetic best.

One of Warner Brothers' `hard-hitting' social comment dramas of the 1930s, They Won't Forget leaves viewers all riled up though, today, maybe less at the judicial process in the Deep South than at Mervyn LeRoy's depiction of it in the movie. Based not too loosely on the Mary Phagan murder case of 1913, it updates the events to the late Depression and also advances the victim's age (Phagan was 13; here, the victim an unrecognizable Lana Turner, in her debut is a student at a small business college).

It's Confederate Memorial Day, April 26, and the college lets out early, unexpectedly for instructor Edward Norris, a Northerner. But Turner returns for the vanity case she's left behind. Hours later, her body is discovered at the base of an elevator shaft. The town prosecutor (Claude Rains, slinging a Southern drawl) smells a political advantage that might propel him to the state senate, an advantage of no use if the perpetrator is only the illiterate black janitor who found her. Suspicion falls on Norris, and soon the judicial establishment, the press and the townspeople have turned against him. Outside help a detective and a defense attorney prove of no avail. Turner is convicted and sentenced to death; when the governor commutes his sentence, he's lynched (as was Leo Frank in the original case). It's fast, brutal and pretty unsentimental.

LeRoy was known for his slam-bang, take-no-prisoners style but here he dawdles at first. Under the credits is a medley of songs of the South, bolstered by quotations from Lincoln and Robert E. Lee to soften up those touchy audiences in Dixie so they won't know what hit them. When he gets up to speed, however, he doesn't slacken, cutting quick to advance the action his movie's an unstoppable steamroller, just like the judicial railroading of the story (the lynching itself, expressed by a mailbag clipped off its hook by a passing train, is especially and darkly adroit).

But there's a near-fatal flaw in the story. We're meant to harbor persuasive doubts as to Norris' guilt, but the possibility of a suspect other than he is never more than fleetingly entertained. The movie purports to document a miscarriage of justice, but it fails to build an ironclad case.

It's Confederate Memorial Day, April 26, and the college lets out early, unexpectedly for instructor Edward Norris, a Northerner. But Turner returns for the vanity case she's left behind. Hours later, her body is discovered at the base of an elevator shaft. The town prosecutor (Claude Rains, slinging a Southern drawl) smells a political advantage that might propel him to the state senate, an advantage of no use if the perpetrator is only the illiterate black janitor who found her. Suspicion falls on Norris, and soon the judicial establishment, the press and the townspeople have turned against him. Outside help a detective and a defense attorney prove of no avail. Turner is convicted and sentenced to death; when the governor commutes his sentence, he's lynched (as was Leo Frank in the original case). It's fast, brutal and pretty unsentimental.

LeRoy was known for his slam-bang, take-no-prisoners style but here he dawdles at first. Under the credits is a medley of songs of the South, bolstered by quotations from Lincoln and Robert E. Lee to soften up those touchy audiences in Dixie so they won't know what hit them. When he gets up to speed, however, he doesn't slacken, cutting quick to advance the action his movie's an unstoppable steamroller, just like the judicial railroading of the story (the lynching itself, expressed by a mailbag clipped off its hook by a passing train, is especially and darkly adroit).

But there's a near-fatal flaw in the story. We're meant to harbor persuasive doubts as to Norris' guilt, but the possibility of a suspect other than he is never more than fleetingly entertained. The movie purports to document a miscarriage of justice, but it fails to build an ironclad case.

Flawless blending of cynicism, humor and tragedy, this re-enactment of a real-life murder in the south consciously downplays the real-life anti-semitism in the real murder of Mary Phagan case, but carry more of an emotional wallop than the Jack Lemmon made-for-TV docudrama -- although the latter is still good on its own terms. Lana Turner has an impressive screen debut as the murder victim. Gloria Dickson is very powerful as the defendant's wife, and Claude Rains is magnificent as the politically minded prosecutor, but Allyn Joslyn as the cynical, burnt out reporter steals the show. A truly excellent example of how historically based movies can be among the most memorable.

Did you know

- TriviaThe novel "Death in the Deep South" and this movie version were based on the notorious murder trial and subsequent lynching of Leo Frank. The film mentions the suspect's Northern background, which was a factor in his lynching, but does not mention that he was Jewish. The real-life victim, Mary Phagan, was only 13 years old, a far cry from Lana Turner's 16-year-old "sweater girl."

- GoofsDuring the entire trial the shadow of the window is showing in the same place; behind the witness chair/over the back door of the courtroom.

- Quotes

Drugstore Clerk: What'll it all be be, ladies?

Imogene Mayfield: Dope and cherry, Fred.

Drugstore Clerk: [to Mary] How about you, half-pint?

Mary Clay: Make mine a chocolate malt and drop an egg in it as fresh as you are.

Drugstore Clerk: The hens don't lay 'em that good.

- ConnectionsFeatured in Hollywood and the Stars: The Angry Screen (1964)

- SoundtracksKingdom Coming

(1862) (uncredited)

aka "The Year of Jubilo"

Music by Henry Clay Work

Played during the opening credits

- How long is They Won't Forget?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Runtime

- 1h 35m(95 min)

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.37 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content