The Buddhist priest wants the Daughter of the Daimyo to become a priestess at the Forbidden Garden. The Daimyo thinks if he were in Europe that his daughter should decide on her own, but he ... Read allThe Buddhist priest wants the Daughter of the Daimyo to become a priestess at the Forbidden Garden. The Daimyo thinks if he were in Europe that his daughter should decide on her own, but he is denounced and has to commit harakiri. She meets Olaf, a European officer, falls in love... Read allThe Buddhist priest wants the Daughter of the Daimyo to become a priestess at the Forbidden Garden. The Daimyo thinks if he were in Europe that his daughter should decide on her own, but he is denounced and has to commit harakiri. She meets Olaf, a European officer, falls in love and marries him, but after a few months he has to return to Europe. She gives birth to a ... Read all

- Director

- Writers

- Stars

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

A daimyo (Paul Biensfeldt) returns from a trip to Europe to a household in some trouble. The local Buddhist priest (Georg John) has set his illicit sights on the daimyo's daughter, O-Take-San (Lil Dagover), insisting that she join the temple as a priestess with obvious ulterior motives. To help break her from her domestic situation, the priest writes to the emperor a lie about how the daimyo has been overcome by Western influences, a single letter enough to convince the emperor to demand the daimyo commit seppuku. The daimyo, being a good servant of the emperor, follows through.

Now, let me take a moment to talk about medieval Japanese culture. I don't know a lot, but I have been watching a whole lot of Japanese movies over the past few months, and the details of so much of this story seem so wrong. It's a lot of little things that mostly just kind of bug me, not really negatively affecting the telling of the story, but just enough to get on my nerves. People walk around inside with sandals on. When we see the one person take off their sandals, they do it on the wrong elevation outside the house. Almost no one ever sits down, on the floor or anywhere else. The women wear their kimonos far too loosely around their legs. The weirdest part, though, is how the priest talks about the Buddha as some sort of vengeful god who will punish those who do not do as the Buddha wishes. I can allow for the priest being a terrible person, lying to get what he wants, but that's so not how the Buddha works in any form of Buddhism I've ever heard about that it sits there as a weird point that simply will not go away. Essentially, this feels like the work of Europeans who grew to love Japanese culture but never learned the details of it.

The details that do work are the production design. There are a fair number of sets, almost all located in Japan, and they have a slightly cluttered by convincing look of Japanese traditional housing. There's a lot of signage and detail that make them convincing places for the characters to inhabit, often feeling oppressed by the detail itself, like the culture itself is manifest in the detail.

O-Take-San gets saved by the brash action of a foreign sailor, Olaf (Niels Prien), who jumps a wall into a forbidden garden where O-Take-San is praying, preparing to become a full priestess of the temple. He marries her for 999 days, according to local law, and they conceive a child. He must sail away, though, and leaves her living in a tea house with a kindly proprietor and the law on her side against the priest's further actions for a time. Olaf, of course, never comes back, leaving her a loyal wife to a disloyal husband who take another wife back in his home country.

Coincidence drives the finale with the Prince Matahari (Meinhart Maur) discovering the priest's duplicitousness, becoming a kind of guardian to O-Take-San, and Olaf receiving an offer to return to Japan, bringing his wife along. It's all pretty standard melodramatic stuff, but O-Take-San's actions that end the film, after she discovers her husband's bigamy, gives a nice wraparound feel to the film that helps to underline the new title for the work.

The problem with the adaptation is that there's a lot of story, the silent approach (not exactly Lang's fault since it was the only way to do movies at the time) undermines the immediacy of the characters, and that lack of character prevents any real emotional connection. The plot's twists and turns feel almost arbitrary, but O-Take-San's final action provides a strong structural ending that I admire.

It's not enough to make the movie good, but it's enough to have convinced me that I hadn't completely wasted my time. That, plus the set design, are really what gives the film what little strength it has.

We can be pretty sure that a film called Harakiri made by Germans in Hamburg, adapted from an American's short story, in turn based on the recollections of the writer's sister who had been to Japan with her missionary husband - layers upon layers of curious, we can bet fascinated but more or less secretly judgmental, European eyes - that all this was never going to unravel what is at the hear of a complex world.

There are tea-houses, geishas on getta sandals, an evil Buddhist priest, the powerful daimyo; the pageantry of barely familiar Japanese characters a caricature, and so the question at this point is just how gross?

I was surprised, because not so much after all. Painstaking effort must have gone into it at the time, and I assume it was a prestige production for Decla-Bioscop - they would be merged with UFA in '21 to write Weimar film history. Oh, Germans playing Japanese is something we'll have to make our peace with. The statue of the Buddha looks crudely unconvincing, and the flowery decorations on wooden panels owe more to the Japonism of art-nouveau then sweeping Europe than traditional Japanese culture.

But as a relic of the time when Japanese images, motifs, patterns had already been transferred - by people like Van Gogh or Monet - to the continental subconscious as new, exciting perspectives of a cherry-blossomed idyll and there replicated in what has since deeply influenced graphic arts as we've come to know them; that is to say, a translation of formal serenity as the suggestively intriguing veil which, once lifted, reveals familiar passions and cruelties that can outwardly reverberate with their proper tragedy.

It is all a bit camp then, with contemporary eyes. The Japanese world narrowed down to a stage where an occidental opera can soar.

As allegory of then recent Japanese history it's strangely friendly to the country, and cleverly succinct; just as we are about to imagine a patronizing conclusion where the Western naval officer - hues of Commodore Perry - redeems the young geisha from the clutches of an evil priest and a rigid political orthodoxy that orders its vassals to take their own lives, he is shown to be the false promise, irresponsible, and ultimately a coward.

See this as an emotionally-charged dream of Japan. Film-wise, it is less cinematic than Japanese woodblock prints from a 100 years before.

PS: the quotation I cited in the summary above is actually spoken in the film by a Buddhist monk who wants to destroy the Japanese woman. Can you think of any god more intimidating than the Buddha? I know I can't.

Mainly interesting to me for the various items from Oriental curio stores used for set decoration and costumes. Few of the cast look Japanese or move in a Japanese manner (walking in a kimono takes practice and women would be embarrassed to show their arms).

I saw the Dutch/Italian restoration, which mostly looks very nice and clean and is nicely tinted. The titles were in Dutch. Running time was about 85 minutes.

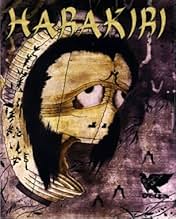

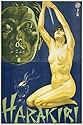

This is one of the minor films (with difference) of the German moviemaker, Fritz Lang. Inspired by John Luther Llong and David Belasco's "Madame Butterfly", "Harakiri" is above all, the triumph of the art direction that shines specially in this Nippon fable in a majestic and suggestive way. "Harakiri" it is not any big and lost Fritz Lang's masterpiece. Thanks to its discovery our idea about the evolution of the posterior career of the German filmmaker has been destroyed. However, this film confirms us Lang's control of story telling, his talent for the construction of narrative and, above all, to validate in a manner, the extraordinary themes consistent in his work.

We encounter in this movie a more naturalist visual conception of the cinema, rather than those works of his contemporaries. The scenery never tries to overlap reality, but in a certain way, tries to remake it. This film was particularly eulogized for the critics of that time for the detail of the nature and the recreation of the Japan of that time. Lang had the invaluable help of the Ethnographic Museum of Berlin, and thanks to this, and on the fact that the director knew by heart oriental civilizations, at the end the result was this film that has to be taken in account as an early Lang.

It is possible to find as well in "Harakiri" certain features very recognizable in his later works, like the theme of love fighting against the external circumstances that try to obstruct its success ("Der Müde Tod" as a perfect example). In this film, love is jeopardized by the social conventions which find their confirmation into the figure of Bonzo; adding another aspect, the religious one, to those dangers that hunt the main characters.

And now, if you'll allow me, I must temporarily take my leave because this German Count must considerer putting into practice those strange and peculiar Japanese customs, that is to say, "Harakiri" due to the remaining days of Christmas preparations.

Herr Graf Ferdinand Von Galitzien http://ferdinandvongalitzien.blogspot.com/

Did you know

- TriviaThe film was originally released in the United States and other countries as Madame Butterfly because of the source material on which it is based and which also inspired Giacomo Puccini's eponymous 1904 opera.

- Alternate versionsThere is an Italian edition of this film on DVD, distributed by DNA srl, "HARAKIRI (1919) + DESTINO (1921)" (2 Films on a single DVD), re-edited with the contribution of film historian Riccardo Cusin. This version is also available for streaming on some platforms.

- How long is Harakiri?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Runtime1 hour 20 minutes

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.33 : 1

Contribute to this page