A black musician marries a woman facing abuse from her stepfather to rescue her. After the marriage, he refuses to introduce her to his mother, fearing his mother's disapproval of her lower ... Read allA black musician marries a woman facing abuse from her stepfather to rescue her. After the marriage, he refuses to introduce her to his mother, fearing his mother's disapproval of her lower socioeconomic status.A black musician marries a woman facing abuse from her stepfather to rescue her. After the marriage, he refuses to introduce her to his mother, fearing his mother's disapproval of her lower socioeconomic status.

- Awards

- 1 nomination total

Charles Gilpin

- Lido Club Gambler

- (uncredited)

Shingzie Howard

- Louise's Maid

- (uncredited)

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

Scar of Shame, The (1927)

*** (out of 4)

Historically important race film (black cast for black crowds) is one of the best I've seen from this genre of films. A rich concert pianist (Harry Henderson) marries an abused poor girl (Lucia Lyn Moses) so that she can escape her abusive stepfather but this leads to tragedy as the girl doesn't know any life other than the ghetto. Sadly a lot of these silent race films are now lost but from the few I've seen I can see why they were controversial back when they were originally released. Like Within Our Gates, this film spends a lot of time bashing black people for their living conditions, alcohol and the "shame" of their race, which is interesting to see since this film was meant for a black crowd. I guess the producers knew black folks would be seeing these films so they wanted to push some sort of moral issue on them. What I also find interesting and somewhat hypocritical is the fact that these race films always put light skinned black people in the lead roles. In fact, if you just looked at the actors in this movie you'd never guess they were black and in several scenes it appears that the actors are wearing make up to make themselves look lighter. I've read a couple books by race experts and they said this was due to the producers hoping these films could sneak into white theaters (they never did).

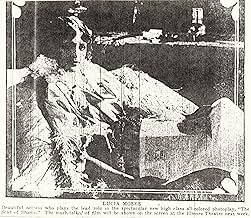

As for the film itself, it's pretty much a remake of Griffith's Broken Blossoms bit it's still very powerful and memorable. The best thing about the movie are the performances, which match any of the actors appearing in Hollywood films at the time. The real highlight is the work of Lucia Lynn Moses, who while filming this was also working at The Cotton Club. She's an incredibly beautiful woman who uses those looks to bring out a certain sadness, which would touch anyone. She's does a remarkable job here and it's a damn shame that this was her only film. The film's final act is pretty predictable and far fetched but it still works pretty well. At times the film pushes its moral lessons a tad bit too strongly but this is still an important film that more people need to see.

*** (out of 4)

Historically important race film (black cast for black crowds) is one of the best I've seen from this genre of films. A rich concert pianist (Harry Henderson) marries an abused poor girl (Lucia Lyn Moses) so that she can escape her abusive stepfather but this leads to tragedy as the girl doesn't know any life other than the ghetto. Sadly a lot of these silent race films are now lost but from the few I've seen I can see why they were controversial back when they were originally released. Like Within Our Gates, this film spends a lot of time bashing black people for their living conditions, alcohol and the "shame" of their race, which is interesting to see since this film was meant for a black crowd. I guess the producers knew black folks would be seeing these films so they wanted to push some sort of moral issue on them. What I also find interesting and somewhat hypocritical is the fact that these race films always put light skinned black people in the lead roles. In fact, if you just looked at the actors in this movie you'd never guess they were black and in several scenes it appears that the actors are wearing make up to make themselves look lighter. I've read a couple books by race experts and they said this was due to the producers hoping these films could sneak into white theaters (they never did).

As for the film itself, it's pretty much a remake of Griffith's Broken Blossoms bit it's still very powerful and memorable. The best thing about the movie are the performances, which match any of the actors appearing in Hollywood films at the time. The real highlight is the work of Lucia Lynn Moses, who while filming this was also working at The Cotton Club. She's an incredibly beautiful woman who uses those looks to bring out a certain sadness, which would touch anyone. She's does a remarkable job here and it's a damn shame that this was her only film. The film's final act is pretty predictable and far fetched but it still works pretty well. At times the film pushes its moral lessons a tad bit too strongly but this is still an important film that more people need to see.

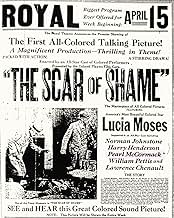

Monday February 6, 7:00pm The Paramount Theater

In a contemporary study of film history The Scar of Shame (1927) has great value as an early surviving example of the "Race Movie" genre. These were motion pictures produced from the silent era through the nineteen-forties using black actors for a black audience in a racially segregated market. Race movies were screened in the schools and churches of small towns as well as theaters in larger cities. The films of Oscar Micheaux were of particular significance in the early days of the genre. "The Scar of Shame" was one of four films produced by The Colored Film Players Corporation of Philadelphia. Harry Henderson (Alvin Hillyard) is a well-educated musician with high aspirations. In an act of altruism he marries Louise Howard (Lucia Lynn Moses) to save her from her abusive Stepfather but is ashamed to take her home to his Mother because she not "in our set". Essentially a well executed melodrama, "The Scar of Shame " is noteworthy for its high production values which indicate a larger than typical budget, as well as elements of colorism and classism.

In a contemporary study of film history The Scar of Shame (1927) has great value as an early surviving example of the "Race Movie" genre. These were motion pictures produced from the silent era through the nineteen-forties using black actors for a black audience in a racially segregated market. Race movies were screened in the schools and churches of small towns as well as theaters in larger cities. The films of Oscar Micheaux were of particular significance in the early days of the genre. "The Scar of Shame" was one of four films produced by The Colored Film Players Corporation of Philadelphia. Harry Henderson (Alvin Hillyard) is a well-educated musician with high aspirations. In an act of altruism he marries Louise Howard (Lucia Lynn Moses) to save her from her abusive Stepfather but is ashamed to take her home to his Mother because she not "in our set". Essentially a well executed melodrama, "The Scar of Shame " is noteworthy for its high production values which indicate a larger than typical budget, as well as elements of colorism and classism.

Despite having an all African-American cast, this film doesn't deal explicitly with race, as its script could have been applied to white people, which is a nice thing for 1927. The film is in part about the dynamic between social classes, and has some good early scenes that deal with that. In one, we see the intertitle "One half the world doesn't know how the other half lives" while a poor woman is scrubbing the laundry over a washboard. Eventually it gets a little bit pushy in its message, which is for people to choose higher aspirations in life (education, the arts, steady jobs) vs. lower (gambling, drinking, violence), making it a simplistic morality tale, and one that is of course directed at the African-American community.

In that sense, it has everything to do with race, and says (1) look, we're people too, not the stereotypes Hollywood and white supremacist culture ordinarily portrays us to be (2) we can do better, that "Our people have much to learn." The plot and the love triangle which develops in the second half is more than a little melodramatic, but the screen presence of all three leads is undeniable (Harry Henderson, Lucia Lynn Moses, and Pearl McCormack), and had these actors been white they all might have been stars of the era. The film is pretty well made as well, making it a silent worth checking out.

In that sense, it has everything to do with race, and says (1) look, we're people too, not the stereotypes Hollywood and white supremacist culture ordinarily portrays us to be (2) we can do better, that "Our people have much to learn." The plot and the love triangle which develops in the second half is more than a little melodramatic, but the screen presence of all three leads is undeniable (Harry Henderson, Lucia Lynn Moses, and Pearl McCormack), and had these actors been white they all might have been stars of the era. The film is pretty well made as well, making it a silent worth checking out.

7tavm

Since it's once again Black History Month, I thought I'd once again review various movies made by people of color for the occasion. This production of the Colored Players Film Corporation (which was co-founded by one African-American, Sherman H. Dudley, a former stage performer) was quite compelling as a cautionary drama though the melodramatic trappings do permeate. Still, there were quite some good performances by the cast of which one of them, a Lucia Lynn Moses, was quite alluring in going from a victimized girl to one trying to be more seductive. It's interesting finding out on this site she filmed this in Philadelphia while also commuting to New York as a chorus girl at the Cotton Club. I don't feel like revealing much else so on that note, I recommend The Scar of Shame.

Having finished reviewing Oscar Micheaux's three silent films that remain accessible to this day ("Within Our Gates," "The Symbol of the Unconquered" (both 1920) and "Body and Soul" (1925)), it was interesting to check out a race film made by others, "The Scar of Shame." While produced and directed by Jewish émigré filmmakers, although perhaps with an integrated crew, it features, in contrast to Micheaux's non-segregated oeuvre, an all-black cast from Colored Players Film Corporation of Philadelphia, with which they made four films, the last of which was this one. Those familiar with Micheaux's films will recognize among the supporting cast former Micheaux regular Lawrence Chenault, who starred in "The Symbol of the Unconquered" and "Body and Soul."

Like Micheaux's films, "The Scar of Shame" is a melodrama, but its singular focus on "uplift" to the exclusion of even the mention of race is in stark contrast to the African-American director's work. Being produced a few years later (sources differ on whether this one is from 1927 or 1929) and evidently with more financing and resources than Micheaux's surviving silents, "The Scar of Shame" does feature superior production values. Improvements in lighting, or the luxury of retakes and censors not ripping the nitrate to shreds, though, are at the expense of sophisticated storytelling, intriguingly complex plotting, greater relevance and an ideology that challenges rather than muddles. For all the technical limitations, I'll take a Micheaux silent over the glitz and classist commentary on class, or "caste," as its titles often put it, of "The Scar of Shame" any day.

That's not to say this film doesn't have more than superficial appeal. Just as a historical record and a glimpse into the depiction of class distinctions in black communities from the 1920s is interesting. Moreover, once the picture picks up, the melodramatics are sometimes amusingly unpredictable until the aggravating conclusion. I hate these old-timey melodrama contrivances that always sacrifice the poor woman (and always a woman, usually of lower class, and often marked by some physical deformity) to make way for a supposedly-happy resolution for the upper-class couple. The same thing annoys me when it happens in, say, a Mary Pickford vehicle such as "Stella Maris" (1918). Micheaux's silents, by contrast, are also remarkable for how advanced they are in the representation of sex, including female protagonists and heroines who rescued the men. You won't find that here. The hero rushes to rescue the damsel-in-distress three times, including once from little more than saving her from accepting a job, I guess. And a woman's scar, which is easily concealed with scarves, is described at one point as completely marring her beauty.

Additionally, if you thought Micheaux was overly didactic, try the hero here practically talking directly to the camera from the get go about uplifting the poors with "the finer things in life," which seems to consist largely of playing piano, a bit of reading and not abusing women. All fine things, indeed, even if every time "finer things" are mentioned I was reminded of the Finer Things Club from "The Office" TV series. It doesn't help that the lead male character here is quite pompous. "Oh! Our people have much to learn!," he bemoans as the picture has long since moved past pictures of Frederick Douglass hanging on the walls to a close-up of a copy of a "True Romance" book, and as the picture's silence on race seems to do little more than support another, more illusory caste system. Talk about mixed messages.

Like Micheaux's films, "The Scar of Shame" is a melodrama, but its singular focus on "uplift" to the exclusion of even the mention of race is in stark contrast to the African-American director's work. Being produced a few years later (sources differ on whether this one is from 1927 or 1929) and evidently with more financing and resources than Micheaux's surviving silents, "The Scar of Shame" does feature superior production values. Improvements in lighting, or the luxury of retakes and censors not ripping the nitrate to shreds, though, are at the expense of sophisticated storytelling, intriguingly complex plotting, greater relevance and an ideology that challenges rather than muddles. For all the technical limitations, I'll take a Micheaux silent over the glitz and classist commentary on class, or "caste," as its titles often put it, of "The Scar of Shame" any day.

That's not to say this film doesn't have more than superficial appeal. Just as a historical record and a glimpse into the depiction of class distinctions in black communities from the 1920s is interesting. Moreover, once the picture picks up, the melodramatics are sometimes amusingly unpredictable until the aggravating conclusion. I hate these old-timey melodrama contrivances that always sacrifice the poor woman (and always a woman, usually of lower class, and often marked by some physical deformity) to make way for a supposedly-happy resolution for the upper-class couple. The same thing annoys me when it happens in, say, a Mary Pickford vehicle such as "Stella Maris" (1918). Micheaux's silents, by contrast, are also remarkable for how advanced they are in the representation of sex, including female protagonists and heroines who rescued the men. You won't find that here. The hero rushes to rescue the damsel-in-distress three times, including once from little more than saving her from accepting a job, I guess. And a woman's scar, which is easily concealed with scarves, is described at one point as completely marring her beauty.

Additionally, if you thought Micheaux was overly didactic, try the hero here practically talking directly to the camera from the get go about uplifting the poors with "the finer things in life," which seems to consist largely of playing piano, a bit of reading and not abusing women. All fine things, indeed, even if every time "finer things" are mentioned I was reminded of the Finer Things Club from "The Office" TV series. It doesn't help that the lead male character here is quite pompous. "Oh! Our people have much to learn!," he bemoans as the picture has long since moved past pictures of Frederick Douglass hanging on the walls to a close-up of a copy of a "True Romance" book, and as the picture's silence on race seems to do little more than support another, more illusory caste system. Talk about mixed messages.

Did you know

- TriviaFilm scholar Donald Bogle called this movie quite possibly the best independent black film of the silent era.

- GoofsAfter Alvin leaves his mother's house, the butler reaches down to pick up the dropped key with his left hand, the next shot is a closeup of him picking up the key with his right hand. The next shot he is standing up with the key in his left hand.

- Quotes

Title Card: One half the world doesn't know how the other half lives.

- Alternate versionsThe Library of Congress Video Collection has a restored version of this film with a new piano score composed and performed by Philip Carli. Its running time is 76 minutes. A small missing section is summarized by an intertitle. Other restoration credits: Simmon, Scott ....... restoration producer Fleming, Dina T. .... restoration production co-ordinator McConnell, Allan .... restoration magnetic recording laboratory head Winther, James ...... restoration videotape transfer and editor Chrisman, Paul ...... restoration music recordist DeAnna, Gene ........ restoration titles

- ConnectionsFeatured in American Experience: Midnight Ramble (1994)

Details

- Runtime

- 1h 8m(68 min)

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.33 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content