IMDb RATING

7.0/10

1.6K

YOUR RATING

Professor Stock and his wife Mizzi are always bickering. Mizzi tries to seduce Dr. Franz Braun, the new husband of her good friend Charlotte.Professor Stock and his wife Mizzi are always bickering. Mizzi tries to seduce Dr. Franz Braun, the new husband of her good friend Charlotte.Professor Stock and his wife Mizzi are always bickering. Mizzi tries to seduce Dr. Franz Braun, the new husband of her good friend Charlotte.

- Awards

- 2 wins total

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

Silent cinema is not inherently inferior to the sound cinema, but many silent pictures, especially those from the early-to-mid 1920s, seem stilted in comparison to their talkie counterparts due to an over-reliance on title cards, and a lack of faith in the audience's ability to "read" images. Fortunately, they aren't all like this, thanks to the inventive boldness of the era's greatest filmmakers.

To start at the very beginning (a very good place to start), The Marriage Circle is the first comedy Ernst Lubitsch made in Hollywood. It's been pointed out that there was an abrupt change in pace compared to his earlier Berlin comedies, which were non-stop riotous farces. This is true, but The Marriage Circle also sees an enormous shift in tone. Lubitsch's pictures in his home country were absurd to the point of being surreal, staged with an emphasis on exaggeration and peopled with theatrical caricatures. The Marriage Circle however depicts a reasonably realistic situation, albeit a comically improbable one. There is no slapstick here, but neither is it a witty verbal comedy. Instead the humour derives from numerous misunderstandings as five characters become innocently entangled a complex love pentagon. In this, the audience is omniscient – we know everything that is going on – whereas each character knows only enough to make them misconstrue. Lubitsch's problem then, was how to convey this to the audience without spoon-feeding them every detail, and above all keep it funny.

He does it, not just by showing us everything, but by showing us how things are seen by everyone. The camera is never merely presentational; it is always within the action. In virtually every shot, we are either seeing things from a character's point of view or we are focusing on a character's reaction. The angles are never external, watching the players interact with one another; they are always down the line, putting us inside the interaction. And Lubitsch is brave enough – and knows we are intelligent enough – to switch quickly from one perspective to another. For example, in the scene where Mizzi (thinking she is onto something) embraces Dr Braun, we go from Muller seeing them from behind and assuming Mizzi is Charlotte, to his seeing Charlotte in the waiting room (and thus realising the woman in the embrace can't have been Charlotte), to Braun realising Charlotte is watching, to Charlotte realising Braun has been dallying with a female patient whom she doesn't realise is Mizzi! As you can see, it all sound rather confusing when put it into words, but on screen it's a cinch to follow.

But that's not all that's going on here. As well as getting the right angles on the action, Lubitsch throws in some subtle tricks to imply rather than state the way things are. In the opening scene, it is clearly established that the Stocks's marriage is not the most harmonious, but it is one simple moment that reveals the true extent of the breakdown. Adolphe Menjou sees his wife get into a cab with another man, assuming (wrongly of course!) she may be having an affair. He turns to the camera, his expression unreadable. And then, slowly, a smile spreads over his face.

And this leads me neatly onto the next point, that it is as much the skills of the actors that make this wordless fiasco workable. The two lead men, Adolphe Menjou and Monte Blue, are not comedy actors in the normal sense, but they exhibit great comic timing and control. Just as the story is believable but unlikely, their performances are naturalistic but extreme. Menjou is the master of the withering glance and the long-suffering sulk. You get the impression, just by looking at his face, that here is a man who was not cut out for marriage. Blue, on the other hand, expertly portrays the complete opposite, a modest and honest man who seems unaware of his own attractiveness. You pick up his character from some neat little gestures; such as him nervously pulling at his collar to cool off – something you normally only see cartoon characters doing. Florence Vidor has the restrained demeanour of the only entirely normal person caught up in this situation, and gives a wonderful straight performance that counterpoints all the others. Creighton Hale is the only one of the players who is somewhat hammy and unrealistic, but as a more marginal and somewhat ridiculous character, he is allowed, and even helps give the picture its slightly silly edge. Marie Prevost is the only one of the five who is not exceptional, but she is by no means bad, and at least fits the part.

Lubitsch himself claimed this was his favourite of all his own pictures, and the only one which if he had to do again he would change nothing. It was well liked by his contemporaries too, and in the dying days of the silent picture you can see a significant move towards more sedate and subtle silent comedies, especially in the work of directors like Rene Clair and Leo McCarey. And after that of course, the talkies would come along, and it would all change again.

To start at the very beginning (a very good place to start), The Marriage Circle is the first comedy Ernst Lubitsch made in Hollywood. It's been pointed out that there was an abrupt change in pace compared to his earlier Berlin comedies, which were non-stop riotous farces. This is true, but The Marriage Circle also sees an enormous shift in tone. Lubitsch's pictures in his home country were absurd to the point of being surreal, staged with an emphasis on exaggeration and peopled with theatrical caricatures. The Marriage Circle however depicts a reasonably realistic situation, albeit a comically improbable one. There is no slapstick here, but neither is it a witty verbal comedy. Instead the humour derives from numerous misunderstandings as five characters become innocently entangled a complex love pentagon. In this, the audience is omniscient – we know everything that is going on – whereas each character knows only enough to make them misconstrue. Lubitsch's problem then, was how to convey this to the audience without spoon-feeding them every detail, and above all keep it funny.

He does it, not just by showing us everything, but by showing us how things are seen by everyone. The camera is never merely presentational; it is always within the action. In virtually every shot, we are either seeing things from a character's point of view or we are focusing on a character's reaction. The angles are never external, watching the players interact with one another; they are always down the line, putting us inside the interaction. And Lubitsch is brave enough – and knows we are intelligent enough – to switch quickly from one perspective to another. For example, in the scene where Mizzi (thinking she is onto something) embraces Dr Braun, we go from Muller seeing them from behind and assuming Mizzi is Charlotte, to his seeing Charlotte in the waiting room (and thus realising the woman in the embrace can't have been Charlotte), to Braun realising Charlotte is watching, to Charlotte realising Braun has been dallying with a female patient whom she doesn't realise is Mizzi! As you can see, it all sound rather confusing when put it into words, but on screen it's a cinch to follow.

But that's not all that's going on here. As well as getting the right angles on the action, Lubitsch throws in some subtle tricks to imply rather than state the way things are. In the opening scene, it is clearly established that the Stocks's marriage is not the most harmonious, but it is one simple moment that reveals the true extent of the breakdown. Adolphe Menjou sees his wife get into a cab with another man, assuming (wrongly of course!) she may be having an affair. He turns to the camera, his expression unreadable. And then, slowly, a smile spreads over his face.

And this leads me neatly onto the next point, that it is as much the skills of the actors that make this wordless fiasco workable. The two lead men, Adolphe Menjou and Monte Blue, are not comedy actors in the normal sense, but they exhibit great comic timing and control. Just as the story is believable but unlikely, their performances are naturalistic but extreme. Menjou is the master of the withering glance and the long-suffering sulk. You get the impression, just by looking at his face, that here is a man who was not cut out for marriage. Blue, on the other hand, expertly portrays the complete opposite, a modest and honest man who seems unaware of his own attractiveness. You pick up his character from some neat little gestures; such as him nervously pulling at his collar to cool off – something you normally only see cartoon characters doing. Florence Vidor has the restrained demeanour of the only entirely normal person caught up in this situation, and gives a wonderful straight performance that counterpoints all the others. Creighton Hale is the only one of the players who is somewhat hammy and unrealistic, but as a more marginal and somewhat ridiculous character, he is allowed, and even helps give the picture its slightly silly edge. Marie Prevost is the only one of the five who is not exceptional, but she is by no means bad, and at least fits the part.

Lubitsch himself claimed this was his favourite of all his own pictures, and the only one which if he had to do again he would change nothing. It was well liked by his contemporaries too, and in the dying days of the silent picture you can see a significant move towards more sedate and subtle silent comedies, especially in the work of directors like Rene Clair and Leo McCarey. And after that of course, the talkies would come along, and it would all change again.

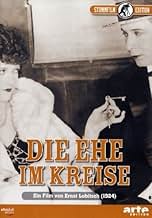

This was actually Ernst Lubitsch's first film for Warner Brothers, he remade it 8 years later as the sublime One Hour With You for Paramount. It's always been difficult for me to not mentally refer to the latter whenever watching this because it's a good film in its own right and is better not compared to the technically and technologically improved later musical version.

In Vienna city of dreams the husband of an ever-flirting wife grasps the opportunity to obtain a divorce on the grounds of her infidelity with the husband of her best friend. And the husbands' best friend fancies his wife too. Farcical situations develop, with the prevailing morals and manners always to the fore, but basically everyone gets what they deserve. Lubitsch's elegant production, the lovely décor, lightly salted frivolous story and human acting proved a big hit at the time and dare I say it, could be ultimately just as rewarding to watch as OHWY. It might have been a little better if it had only been 10 minutes shorter some of the scenes are stultifyingly languorous, but I'm not really complaining.

Although neither version ended satisfactorily, this was still a wonderful piece of film-making, a foretaste of things to come from Lubitsch and above all else, nice entertainment.

In Vienna city of dreams the husband of an ever-flirting wife grasps the opportunity to obtain a divorce on the grounds of her infidelity with the husband of her best friend. And the husbands' best friend fancies his wife too. Farcical situations develop, with the prevailing morals and manners always to the fore, but basically everyone gets what they deserve. Lubitsch's elegant production, the lovely décor, lightly salted frivolous story and human acting proved a big hit at the time and dare I say it, could be ultimately just as rewarding to watch as OHWY. It might have been a little better if it had only been 10 minutes shorter some of the scenes are stultifyingly languorous, but I'm not really complaining.

Although neither version ended satisfactorily, this was still a wonderful piece of film-making, a foretaste of things to come from Lubitsch and above all else, nice entertainment.

This was Lubitsch's first film for Paramount following Rosita with Mary Pickford and sees him in transcendent form.

A highly sophisticated comedy set in Vienna (possibly to allow for the outrageous conduct of the characters)and rich in complex farce scenarios and intelligent narrative twists played by an excellent cast.

Marie Prevost is extraordinary as the relentless pursuer of the happily married Dr Franz Braum, happily married that is to her best friend played by Florence Vidor. Adolphe Menjou offers a characteristically fine performance as the betrayed husband seeking divorce from his wayward wife. His expressions are hysterical as he reveals his caustic feelings towards his spouse. This film explores issues of marriage, commitment, fidelity and temptation in the Lubitsch style. A very funny, touching comedy that displays Lubitsch's talent for understated sophisticated comedy. This stands alongside some of his best films such as The Shop Around the Corner and To Be or Not to be as an equal.

A highly sophisticated comedy set in Vienna (possibly to allow for the outrageous conduct of the characters)and rich in complex farce scenarios and intelligent narrative twists played by an excellent cast.

Marie Prevost is extraordinary as the relentless pursuer of the happily married Dr Franz Braum, happily married that is to her best friend played by Florence Vidor. Adolphe Menjou offers a characteristically fine performance as the betrayed husband seeking divorce from his wayward wife. His expressions are hysterical as he reveals his caustic feelings towards his spouse. This film explores issues of marriage, commitment, fidelity and temptation in the Lubitsch style. A very funny, touching comedy that displays Lubitsch's talent for understated sophisticated comedy. This stands alongside some of his best films such as The Shop Around the Corner and To Be or Not to be as an equal.

Through the urging of actress Mary Pickford, Austrian Ernst Lubitsch sailed to America to direct her dramatic film 1923's 'Rosita.' Newly-formed Warner Brothers Studio, familiar with Lubitsch's well-earned reputation in producing light-hearted comedies, signed him immediately to a three-year, six picture contract, giving him the right to select his actors and film crew. So unusual was the contract at the time, the studio also granted him final say on the finished motion picture.

Lubitsch rolled up his sleeves and directed what became his signature trademark: a sophisticated romantic comedy that suggested rather than overtly displaying possible infidelities in a marriage. His February 1924 "The Marriage Circle" was the director's first American comedy, jump-starting an impressive body of work still studied today by film academia.

"The Marriage Circle" consists of three couples: one, Charlotte (Marie Prevost), instigates a series of hinted extra-marital affairs in two other marriages. Inspired by Charlie Chaplin's 'A Woman of Paris,' Lubitsch saw the possibilities of well-meaning events having the potential of spiraling out of control when one spouse suspects the other of cheating when an innocent act is interpreted the wrong way.

Based on a Lothar Schmidt play, 'Only A Dream,' "The Marriage Circle" begins with the morning ritual of a couple ignoring one another, establishing a cold relationship between the two. Professor Josef Stock (Adolphe Menjou) is the disgruntled hubby unhappy with his selfish wife, Charlotte. Spotting her getting into a cab with a gentleman (Monte Blue), who's actually a stranger picking up flowers for his wife, Stock immediately suspects the worst and hires a detective to tail his wife. 'The Lubitsch touch,' a much-interpreted term applied to the director's style of sophisticated, witty charm mixed in with a dose of nuanced sexuality, is first seen in an American production in "The Marriage Circle." Marie Prevost, who played Charlotte, was a early favorite actress of Lubitsch when he first came to the United States. She played in several of his films before released by Warner Brothers in 1926. Her roles on the screen diminished after that. She became depressed and turned to alcohol and food, gaining a lot of weight in the process. She died at the age of 38 on January 1937, leaving only $300 in her estate. Her post-career poverty was given as a prime example of spurring the Hollywood community to rally around the proposed Motion Picture Country House and Hospital, operated by a charitable group designed to provide assistance and residential care for those in the film industry who are undergoing financial hardships later in life.

So admired has been "The Marriage Circle" that the American Film Institution nominated it for the Top 100 Funniest Movies of All Time as well as a nominee for its Top 100 America's Greatest Love Story Movies. Directors as diverse as Alfred Hitchcock, Yasujiro Ozu, Jean Renoir, and Douglas Sirk all expressed an affection towards Lubitsch's second American film.

Lubitsch rolled up his sleeves and directed what became his signature trademark: a sophisticated romantic comedy that suggested rather than overtly displaying possible infidelities in a marriage. His February 1924 "The Marriage Circle" was the director's first American comedy, jump-starting an impressive body of work still studied today by film academia.

"The Marriage Circle" consists of three couples: one, Charlotte (Marie Prevost), instigates a series of hinted extra-marital affairs in two other marriages. Inspired by Charlie Chaplin's 'A Woman of Paris,' Lubitsch saw the possibilities of well-meaning events having the potential of spiraling out of control when one spouse suspects the other of cheating when an innocent act is interpreted the wrong way.

Based on a Lothar Schmidt play, 'Only A Dream,' "The Marriage Circle" begins with the morning ritual of a couple ignoring one another, establishing a cold relationship between the two. Professor Josef Stock (Adolphe Menjou) is the disgruntled hubby unhappy with his selfish wife, Charlotte. Spotting her getting into a cab with a gentleman (Monte Blue), who's actually a stranger picking up flowers for his wife, Stock immediately suspects the worst and hires a detective to tail his wife. 'The Lubitsch touch,' a much-interpreted term applied to the director's style of sophisticated, witty charm mixed in with a dose of nuanced sexuality, is first seen in an American production in "The Marriage Circle." Marie Prevost, who played Charlotte, was a early favorite actress of Lubitsch when he first came to the United States. She played in several of his films before released by Warner Brothers in 1926. Her roles on the screen diminished after that. She became depressed and turned to alcohol and food, gaining a lot of weight in the process. She died at the age of 38 on January 1937, leaving only $300 in her estate. Her post-career poverty was given as a prime example of spurring the Hollywood community to rally around the proposed Motion Picture Country House and Hospital, operated by a charitable group designed to provide assistance and residential care for those in the film industry who are undergoing financial hardships later in life.

So admired has been "The Marriage Circle" that the American Film Institution nominated it for the Top 100 Funniest Movies of All Time as well as a nominee for its Top 100 America's Greatest Love Story Movies. Directors as diverse as Alfred Hitchcock, Yasujiro Ozu, Jean Renoir, and Douglas Sirk all expressed an affection towards Lubitsch's second American film.

Settling in Hollywood and freed from the whims of Mary Pickford, Ernst Lubitsch moved from the independent distributor United Artists to the minor studio Warner Brothers where he was allowed to make the first film in his career that really feels like a Lubitsch film. He'd touched on the ideas and tone here and there, mostly in his comedies The Doll and The Oyster Princess, but there was an embrace of silly physical comedy that seemed a bit out of step with his later work while engaging in more overt forms of farce. Not to imply that those didn't work, but they were just different. Now, with The Marriage Circle, Lubitsch was quickly settling into his domestic and romantic concerns between men and women that embrace wittiness rather than silliness.

Set in Vienna, the film is the story of two couples and a single man. The first couple are Professor Josef Stock (Adolphe Menjou) and his wife Mizzie (Marie Prevost), a pair who have been married for some time and have lost the spark of romance between them. Mizzie is best friends to Charlotte (Florence Vidor) who is newly married to Dr. Braun (Monte Blue), and the couple are deeply, earnestly in love. Dr. Braun has an associate, Dr. Mueller (Creighton Hale) who is smitten with Charlotte but also has the wherewithal to not actually act on it. Jealousy, intended adultery, and mistaken intentions end up driving the plot of the film as Mizzie decides that she's going to have an affair with Dr. Braun because he can obviously bring romance to her that her husband no longer offers. Meanwhile, Charlotte confides in Mizzie because she thinks that Dr. Braun is actually intent on an affair with the young Miss Hofer (Esther Ralston), and Professor Stock is so convinced of his wife's infidelity that he hires a private detective to follow her and gather evidence (that he guarantees he'll collect and lead to a divorce).

The joys in the film early are the lightly farcical elements, mostly around Charlotte thinking that Dr. Braun is infatuated with Miss Hofer, so she ends up pushing Mizzie towards Dr. Braun, thinking that it will blunt Dr. Braun's potential infidelities. The look on Mizzie's face as Charlotte literally pushes her into Dr. Braun's arms during a dance is really funny. And yet, there's always a satirical and sharp edged undertone to what's going on. Charlotte knows that something is wrong somewhere, and she trusts the one woman she shouldn't to help fix it. That helps the film veer really closely to something far more tragic than it turns out to be.

Dr. Braun ends up being a good man caught up in the wiles of an unscrupulous woman, and it seems like everything is going to go against him. Dr. Mueller thinks that he's cheating on his wife with Mizzie. Mizzie thinks he's just playing hard to get. Professor Stock ends up convinced, through his private investigator's work, that Dr. Braun is definitely having an affair with Mizzie. It's Dr. Braun's social standing that's at risk here, never his business or his life, but you can feel the edges of everything collapsing around him even though he has no way of making it better despite his best efforts. For a solid twenty minutes, I was convinced that this was going to be a tragedy.

And then things turn around. Just desserts are served. Social reputations are saved, and Dr. Braun ends up with the last laugh while two unlikely potential lovers end up leaving Vienna together. There's real delight in this ending because the character work had been so solidly built.

Now, I've complained pretty consistently that Lubitsch's characters have been thin through his silent period, in particular in his more tragic skewing historical films. I wonder if that's something to do with the writer of the film's scenario, Paul Bern, an Irving Thalberg devotee later in life. Lubitsch had regularly worked with Hanns Kraly and Norbert Falk while in Germany, but Bern seems to have understood how to build character in a silent film more naturally. The film's story is stripped of unnecessaries. It's not intimately tied to Vienna itself and could honestly have taken place in any major city of the time. The jobs of the individuals aren't that important and rarely get mentioned or really addressed directly. It's really about building up a cache of five characters and letting them operate within the rather plain looking surroundings, offering them a chance to bring themselves out of the realm of caricature and into actual character. Lubitsch allows his camera to let Mizzie be herself, her own awful self, and Stock to be himself, his own, detached self, in such a way that their relationship makes sense quickly, setting the groundwork very efficiently for Mizzie to understandably form designs on a more romantic man than her own husband.

The Marriage Circle is quite comfortably Lubitsch's most successful film up to this point. Whether it was the freedom from German company Ufa's house styles, his former writers, lessons he'd learned working for Mary Pickford, or the introduction of a new, talented writer in Paul Bern, Lubitsch was finding his voice more comfortably than ever. It may not end up being one of Lubitsch's great films, but it's the first film that is firmly Lubitsch while also being consistently entertaining and even a bit touching.

Set in Vienna, the film is the story of two couples and a single man. The first couple are Professor Josef Stock (Adolphe Menjou) and his wife Mizzie (Marie Prevost), a pair who have been married for some time and have lost the spark of romance between them. Mizzie is best friends to Charlotte (Florence Vidor) who is newly married to Dr. Braun (Monte Blue), and the couple are deeply, earnestly in love. Dr. Braun has an associate, Dr. Mueller (Creighton Hale) who is smitten with Charlotte but also has the wherewithal to not actually act on it. Jealousy, intended adultery, and mistaken intentions end up driving the plot of the film as Mizzie decides that she's going to have an affair with Dr. Braun because he can obviously bring romance to her that her husband no longer offers. Meanwhile, Charlotte confides in Mizzie because she thinks that Dr. Braun is actually intent on an affair with the young Miss Hofer (Esther Ralston), and Professor Stock is so convinced of his wife's infidelity that he hires a private detective to follow her and gather evidence (that he guarantees he'll collect and lead to a divorce).

The joys in the film early are the lightly farcical elements, mostly around Charlotte thinking that Dr. Braun is infatuated with Miss Hofer, so she ends up pushing Mizzie towards Dr. Braun, thinking that it will blunt Dr. Braun's potential infidelities. The look on Mizzie's face as Charlotte literally pushes her into Dr. Braun's arms during a dance is really funny. And yet, there's always a satirical and sharp edged undertone to what's going on. Charlotte knows that something is wrong somewhere, and she trusts the one woman she shouldn't to help fix it. That helps the film veer really closely to something far more tragic than it turns out to be.

Dr. Braun ends up being a good man caught up in the wiles of an unscrupulous woman, and it seems like everything is going to go against him. Dr. Mueller thinks that he's cheating on his wife with Mizzie. Mizzie thinks he's just playing hard to get. Professor Stock ends up convinced, through his private investigator's work, that Dr. Braun is definitely having an affair with Mizzie. It's Dr. Braun's social standing that's at risk here, never his business or his life, but you can feel the edges of everything collapsing around him even though he has no way of making it better despite his best efforts. For a solid twenty minutes, I was convinced that this was going to be a tragedy.

And then things turn around. Just desserts are served. Social reputations are saved, and Dr. Braun ends up with the last laugh while two unlikely potential lovers end up leaving Vienna together. There's real delight in this ending because the character work had been so solidly built.

Now, I've complained pretty consistently that Lubitsch's characters have been thin through his silent period, in particular in his more tragic skewing historical films. I wonder if that's something to do with the writer of the film's scenario, Paul Bern, an Irving Thalberg devotee later in life. Lubitsch had regularly worked with Hanns Kraly and Norbert Falk while in Germany, but Bern seems to have understood how to build character in a silent film more naturally. The film's story is stripped of unnecessaries. It's not intimately tied to Vienna itself and could honestly have taken place in any major city of the time. The jobs of the individuals aren't that important and rarely get mentioned or really addressed directly. It's really about building up a cache of five characters and letting them operate within the rather plain looking surroundings, offering them a chance to bring themselves out of the realm of caricature and into actual character. Lubitsch allows his camera to let Mizzie be herself, her own awful self, and Stock to be himself, his own, detached self, in such a way that their relationship makes sense quickly, setting the groundwork very efficiently for Mizzie to understandably form designs on a more romantic man than her own husband.

The Marriage Circle is quite comfortably Lubitsch's most successful film up to this point. Whether it was the freedom from German company Ufa's house styles, his former writers, lessons he'd learned working for Mary Pickford, or the introduction of a new, talented writer in Paul Bern, Lubitsch was finding his voice more comfortably than ever. It may not end up being one of Lubitsch's great films, but it's the first film that is firmly Lubitsch while also being consistently entertaining and even a bit touching.

Did you know

- TriviaMotion Picture Magazine (February-July 1924): 'In making the kissing scene in "The Marriage Circle," where the dutiful wife smacks another man other than her husband by mistake, Herr Lubitsch made Florence Vidor and Creighton Hale repeat the event exactly thirty-nine times before the kiss was right. Florence is a very lovely lady, but... well, thirty-nine times!'

- GoofsOn the letter that Dr. Braun writes asking Mizzi to choose another doctor, the printed address on Dr. Braun's stationery misspells Vienna as "Wein"; it is correctly printed as "Wien" as a return address on the envelope of the same letter.

- How long is The Marriage Circle?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box office

- Budget

- $212,000 (estimated)

- Runtime

- 1h 25m(85 min)

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.33 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content