IMDb RATING

7.7/10

18K

YOUR RATING

Four historical tales depict the ongoing human struggle against prejudice and inhumanity.Four historical tales depict the ongoing human struggle against prejudice and inhumanity.Four historical tales depict the ongoing human struggle against prejudice and inhumanity.

- Awards

- 2 wins total

F.A. Turner

- The Dear One's Father

- (as Fred Turner)

Julia Mackley

- Uplifter

- (as Mrs. Arthur Mackley)

John P. McCarthy

- Prison Guard

- (as J.P. McCarthy)

Featured reviews

This silent film by director D.W. Griffith is well known to serious movie buffs and historians, but not to today's general public. I doubt that a lot of people these days would have the patience to sit through a film that contained three hours of silence. Nevertheless, the film's technical innovations inspired filmmakers in the 1920's and later, particularly in Russia and Japan. It also inspired filmmakers in the U.S., including Cecil B. DeMille and King Vidor. For this reason, and for other reasons, "Intolerance" is an important film.

The film's four interwoven stories, set in four different historical eras, are tied together thematically by the subject of "intolerance", a word which could be accurately interpreted today as "oppression", "injustice", "hate", "violence", and mankind's general inhumanity.

Griffith's narrative structure, though innovative, is uneven, because he gives more screen time to two of the four stories (the "modern" and the "Babylonian"). Equal time for three stories, thus deleting the fourth, might have worked better.

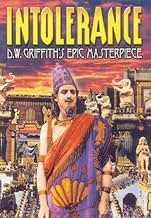

To me, the Babylonian story is the most interesting one because of its more complete coverage, and because of its elaborate costumes and spectacular sets. Even though there is no script, the viewer can easily discern the plot, which suggests that some of today's films might be just as effective, or more so, if screenwriters would downsize the dialogue.

What "Intolerance" offers most of all to contemporary viewers is a sense of perspective. Someone once said that despite the enormous advances in technology, society itself has advanced not at all. That may be true. In the eighty plus years since the film was released, technical advances in film-making have been obvious and impressive. But we are still plagued with the same old human demons of oppression, injustice, hate, violence, and ... intolerance.

The film's four interwoven stories, set in four different historical eras, are tied together thematically by the subject of "intolerance", a word which could be accurately interpreted today as "oppression", "injustice", "hate", "violence", and mankind's general inhumanity.

Griffith's narrative structure, though innovative, is uneven, because he gives more screen time to two of the four stories (the "modern" and the "Babylonian"). Equal time for three stories, thus deleting the fourth, might have worked better.

To me, the Babylonian story is the most interesting one because of its more complete coverage, and because of its elaborate costumes and spectacular sets. Even though there is no script, the viewer can easily discern the plot, which suggests that some of today's films might be just as effective, or more so, if screenwriters would downsize the dialogue.

What "Intolerance" offers most of all to contemporary viewers is a sense of perspective. Someone once said that despite the enormous advances in technology, society itself has advanced not at all. That may be true. In the eighty plus years since the film was released, technical advances in film-making have been obvious and impressive. But we are still plagued with the same old human demons of oppression, injustice, hate, violence, and ... intolerance.

I saw a four hour, ten minute version of this as the University of Chicago's Ida Noyes Hall in February, 1993 -- restored with stills and copyright photos, with a new score by Gillian Anderson, featuring the composer conducting the University Symphony Orchestra -- what an experience!

And where, oh where, is this restored version to be seen today?

Somebody get on the copyright owner's case to release the 4:10 version, with Gillian Anderson's score!

This fine film, possibly the quintessential Griffith, has been in the shadow of the notorious Birth of a Nation too long. (Of course, without Birth of a Nation's controversy, this might never have been made). Intolerance has more spectacle than Birth, far more "speaking" parts (if that's not an oxymoron, I don't know what is!), and is far more PC -- but not in a negative way.

See it, in any form you can!

And where, oh where, is this restored version to be seen today?

Somebody get on the copyright owner's case to release the 4:10 version, with Gillian Anderson's score!

This fine film, possibly the quintessential Griffith, has been in the shadow of the notorious Birth of a Nation too long. (Of course, without Birth of a Nation's controversy, this might never have been made). Intolerance has more spectacle than Birth, far more "speaking" parts (if that's not an oxymoron, I don't know what is!), and is far more PC -- but not in a negative way.

See it, in any form you can!

Four storylines are followed. The first is set in the modern world, where The Dear One (Mae Marsh) and her beloved The Boy (Bobby Harron) are struggling to survive. He loses his job due to union striking after a pay cut mandated so that the company boss can fund his sister's charity work. That same charity takes away the Dear One's child, citing neglect, as the Boy is sent to jail after resorting to crime.

The Biblical "Judean" story recounts how intolerance led to the crucifixion of Jesus. This sequence is the shortest of the four.

The third story details the events of the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre of 1572 where Huguenot protestants were killed under orders of the Catholic royalty.

The fourth story is set in ancient Babylon, and deals with a religious struggle between different sects that leads to their conquest by the Persians.

Griffith's masterpiece is a marvel of narrative and structural complexity for the time, and the Babylon scenes are truly awe-inspiring in their scope and ambition. The story, in which instances of "intolerance" are illustrated throughout the ages, is a bit muddled and more than a little pretentious, but the visualization is second-to-none.

It's been put forth that Griffith made this as a sort of apologia for the racial insensitivity of his previous mega-hit The Birth of a Nation, but Griffith scholars disagree, and say that Griffith was never ashamed by the racist nature of his last movie, and that the intolerance that he was speaking out against was that which had been directed at him over that film (shades of our current political climate).

Regardless, this ended up being the most expensive film ever made up to that point, and was a major flop at the box office, from which Griffith never really recovered. The film now stands as a colossal achievement, and a precursor to historical epics to come. There are various versions in circulation.

The Biblical "Judean" story recounts how intolerance led to the crucifixion of Jesus. This sequence is the shortest of the four.

The third story details the events of the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre of 1572 where Huguenot protestants were killed under orders of the Catholic royalty.

The fourth story is set in ancient Babylon, and deals with a religious struggle between different sects that leads to their conquest by the Persians.

Griffith's masterpiece is a marvel of narrative and structural complexity for the time, and the Babylon scenes are truly awe-inspiring in their scope and ambition. The story, in which instances of "intolerance" are illustrated throughout the ages, is a bit muddled and more than a little pretentious, but the visualization is second-to-none.

It's been put forth that Griffith made this as a sort of apologia for the racial insensitivity of his previous mega-hit The Birth of a Nation, but Griffith scholars disagree, and say that Griffith was never ashamed by the racist nature of his last movie, and that the intolerance that he was speaking out against was that which had been directed at him over that film (shades of our current political climate).

Regardless, this ended up being the most expensive film ever made up to that point, and was a major flop at the box office, from which Griffith never really recovered. The film now stands as a colossal achievement, and a precursor to historical epics to come. There are various versions in circulation.

How on Earth was D.W Griffith able to make this movie back in 1916? Back in the days when the audience were having a hard time focusing on two parallell stories, Griffith gave them four... This is a tremendous spectacle, way ahead of its time, and hardly dated at all. OK, the acting is a little bit over the edge (although Mae Marsh is a personal favourite of mine) and the subtitles are sometimes ridiculous, but the message that this movie brings is absolutely timeless. In fact, this is really the first movie with a vision, an idea. A major influence on Russian director Eisenstein, one has to wonder: Would there have been a Potemkin without this masterpiece? The Birth of a nation is in some ways superior to Intolerance, but for pure strength, innovation and boldness, Intolerance is unsurpassed and unsurpassable. The greatest movie of all times.

My primary interest in this was as a foundation of cinema; so an academic interest, but - having influenced so many things I am very keen on - not without some excitement at the prospect of discovery of this early common source.

So much of cinema flows out from this; a host of recognizable names tutored on set - Von Stroheim, Tod Browning, Woody Van Dyke, Victor Fleming, Elmer Clifton, Jack Conway, King Vidor - and even more once the film rippled across the world. In Moscow, it was the raw material film students were given to dismantle in Lev Kuleshov's fledgling film school, the first ever. And in France Abel Gance must have been awe-struck by the sheer size of the canvas, if his own films offer any clue.

So yes, a fast-paced, lavish blockbuster - it cost at the time an unprecedented $2m to make - with literally a cast of thousands animating history, the story of Hollywood excess begins here - in Italy it had started earlier, with their Roman spectacles. The filmmaker as god, who does not simply photograph reality but constructs entire worlds, permits our vision to travel in the places that we could earlier only imagine.

But the fundamental technique is still from the theatre; that means a grand stage - elevated from us, separate - with every now and then a different backdrop, actors who pantomime sweeping emotion, the eye usually fixed in a distance. Oh the camera moves, but it moves with the stage. And what a grand stage it is.

I suppose it must have been desirable at the time when cinema, and so the possibilities of seeing, made the world feel so new and perhaps so alive again, when so many of the trials and heroism of the world narrative were yet to be immortalized in this new way, that a film like this should try to encompass so much; the Crucifixion, medieval France, ancient Babylon, they're all urgently envisioned in the same space.

It is in more ways than one that Griffith wrote the history of cinema then; by pioneering what he did in terms of a film language, but also by creating a vast expanse - a daunting 3 hours of film - that fills the prehistoric void, in terms of cinema, with a cachet of images, that creates a history of images. Now with the Pharisees or at the Persian camp of Cyrus, the court of Catherine or the harems of Babylon, common streets old and new; now we could point back and see, in a small measure, a history of film gathered in one place. So, when Kuleshov had tasked his students to rework the film, the choice was wise. There is so much here in terms of images, and so fertile for remodeling, that essentially he was presenting them with the empty sheet to write music on - that music, a deeply modernist product of synthesis, we called montage.

What does this filmmaker - as god - see though, what kind of worldview does he spring into life, this is more interesting I believe.

The title summarizes well. So, a cruel - but institutionalized, thus state sanctioned - evil threatening to engulf and dissolve all that is kind, which is the individual life, and of course the warm sentimentality that eventually restores faith in the personal struggle. But nothing casts a shadow in this world, no depth or dimension beyond the plainly conceivable. So the people are straight-forward beings, either good or bad - our heroine is simply called The Dear One - or misguided at their most complex; or, when en masse, they are part of the decor, collectively writhing in some extravagant background.

By the end, a heavenly chorus of angels illuminate the sky above a battlefield. The immediate contrast, like so much in the film, disarms with how much painstaking vision must have gone into making something so splendorous yet so naive. We can pretend like we ought to make amends with the time it was made, just like we can't pretend to look away with indifference, but the point remains; far more complex works of art had been made before, far less didactic about their humanitarian values.

You should at least see the segment with the siege of Babylon though, and the final scenes cross-cutting across time and space as we rush to the climax; it's things like these that so much was founded on.

(And another image that I recommend to those of you who have been charting all this; it is an inexplicable, tight close-up of the girl who is almost brushing, breathing into the camera. It happens once, and suggests intimacy that is never again encountered in the film. It's as though the girl, and so this cinema, is yearning to cross over into a new kind of film where faces hold all the mysteries and performances visualize innermost soul. Jean Epstein would make those films, ushering us in a new perception)

So much of cinema flows out from this; a host of recognizable names tutored on set - Von Stroheim, Tod Browning, Woody Van Dyke, Victor Fleming, Elmer Clifton, Jack Conway, King Vidor - and even more once the film rippled across the world. In Moscow, it was the raw material film students were given to dismantle in Lev Kuleshov's fledgling film school, the first ever. And in France Abel Gance must have been awe-struck by the sheer size of the canvas, if his own films offer any clue.

So yes, a fast-paced, lavish blockbuster - it cost at the time an unprecedented $2m to make - with literally a cast of thousands animating history, the story of Hollywood excess begins here - in Italy it had started earlier, with their Roman spectacles. The filmmaker as god, who does not simply photograph reality but constructs entire worlds, permits our vision to travel in the places that we could earlier only imagine.

But the fundamental technique is still from the theatre; that means a grand stage - elevated from us, separate - with every now and then a different backdrop, actors who pantomime sweeping emotion, the eye usually fixed in a distance. Oh the camera moves, but it moves with the stage. And what a grand stage it is.

I suppose it must have been desirable at the time when cinema, and so the possibilities of seeing, made the world feel so new and perhaps so alive again, when so many of the trials and heroism of the world narrative were yet to be immortalized in this new way, that a film like this should try to encompass so much; the Crucifixion, medieval France, ancient Babylon, they're all urgently envisioned in the same space.

It is in more ways than one that Griffith wrote the history of cinema then; by pioneering what he did in terms of a film language, but also by creating a vast expanse - a daunting 3 hours of film - that fills the prehistoric void, in terms of cinema, with a cachet of images, that creates a history of images. Now with the Pharisees or at the Persian camp of Cyrus, the court of Catherine or the harems of Babylon, common streets old and new; now we could point back and see, in a small measure, a history of film gathered in one place. So, when Kuleshov had tasked his students to rework the film, the choice was wise. There is so much here in terms of images, and so fertile for remodeling, that essentially he was presenting them with the empty sheet to write music on - that music, a deeply modernist product of synthesis, we called montage.

What does this filmmaker - as god - see though, what kind of worldview does he spring into life, this is more interesting I believe.

The title summarizes well. So, a cruel - but institutionalized, thus state sanctioned - evil threatening to engulf and dissolve all that is kind, which is the individual life, and of course the warm sentimentality that eventually restores faith in the personal struggle. But nothing casts a shadow in this world, no depth or dimension beyond the plainly conceivable. So the people are straight-forward beings, either good or bad - our heroine is simply called The Dear One - or misguided at their most complex; or, when en masse, they are part of the decor, collectively writhing in some extravagant background.

By the end, a heavenly chorus of angels illuminate the sky above a battlefield. The immediate contrast, like so much in the film, disarms with how much painstaking vision must have gone into making something so splendorous yet so naive. We can pretend like we ought to make amends with the time it was made, just like we can't pretend to look away with indifference, but the point remains; far more complex works of art had been made before, far less didactic about their humanitarian values.

You should at least see the segment with the siege of Babylon though, and the final scenes cross-cutting across time and space as we rush to the climax; it's things like these that so much was founded on.

(And another image that I recommend to those of you who have been charting all this; it is an inexplicable, tight close-up of the girl who is almost brushing, breathing into the camera. It happens once, and suggests intimacy that is never again encountered in the film. It's as though the girl, and so this cinema, is yearning to cross over into a new kind of film where faces hold all the mysteries and performances visualize innermost soul. Jean Epstein would make those films, ushering us in a new perception)

Did you know

- TriviaDuring filming of the battle sequences, many of the extras got so into their characters that they caused real injury to one another. At the end of one shooting day, a total of 60 injuries were treated at the production's hospital tent.

- GoofsOne of the early title cards in the Judean sequence refers to Jesus having been from "the carpenter shop in Bethlehem". Though he was born in Bethlehem, he worked with his father in a carpenter shop in Nazareth, which is why he was known as Jesus of Nazareth.

- Quotes

Intertitle: When women cease to attract men, they often turn to reform as a second option.

- Crazy creditsConstance Talmadge is credited as 'Georgia Pearce' for her performance as Marguerite de Valois in the French Story. She is credited under her own name in the role of The Mountain Girl in the Babylonian Story.

- Alternate versionsThe movie was officially restored in 1989 by Kevin Brownlow and David Gill for Thames Television. It was transferred from the best available 35mm materials, color-tinted per D.W. Griffith's intent, and contains a digitally recorded orchestral score by Carl Davis. This 176-minute version was released on video worldwide, but has never been telecast in the U.S.

- ConnectionsEdited into La Chute de Babylone (1919)

- How long is Intolerance?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box office

- Budget

- $385,907 (estimated)

- Runtime

- 2h 43m(163 min)

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.33 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content