IMDb RATING

7.1/10

10K

YOUR RATING

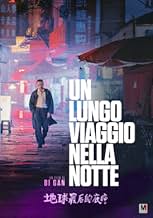

A man went back to Guizhou, found the tracks of a mysterious woman. He recalls the summer he spent with her twenty years ago.A man went back to Guizhou, found the tracks of a mysterious woman. He recalls the summer he spent with her twenty years ago.A man went back to Guizhou, found the tracks of a mysterious woman. He recalls the summer he spent with her twenty years ago.

- Awards

- 15 wins & 45 nominations total

Ming-Dow

- Traffic Police

- (as Ming Dow)

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

This film (which bears absolutely no resemblance to the well-known play with which it shares a title) is first and foremost an art film. Rather than containing a logical story, it is more about mood, tone, and memory. But it captures those things about as well as any film ever has.

It borrows a great deal from previous films in the art genre, including THE MIRROR as well as the films of Wong Kar-wai and Apichatpong Weerasethakul. So if you enjoy those kinds of films, this one is for you. It also has one of the best dream sequences of all time. Recommend for fans of Asian art films.

It borrows a great deal from previous films in the art genre, including THE MIRROR as well as the films of Wong Kar-wai and Apichatpong Weerasethakul. So if you enjoy those kinds of films, this one is for you. It also has one of the best dream sequences of all time. Recommend for fans of Asian art films.

"Long Day's Journey Into Night" is a dazzling and captivating look into the mind of one man's obsession with a woman who disappeared inexplicably from his life several years ago, and his odyssey to uncover her current location. As China's most financially successful arthouse release in history, foreign audiences will be equally captivated by this admittedly strange film's humanity, surrealism, and bizarre familiarity.

I first came to hear of this film after reading the extraordinary hype around its cinematography, which features a staggering 55-minute long cut that continues until the end of the film. Let me be abundantly clear that every ounce of this hype is deserved; perhaps even an understatement.

"Long Day's Journey" is quite possibly the most aesthetically beautiful film I've ever seen. If not, it is certainly in the top five. Nearly every single frame of this film looks like it could belong in an art museum. It is shot impeccably, without error, for its entire 133 minute runtime. The cinematographers -- of which there are three -- heavily rely on color contrast, distortion in the shape of oscillating water, gorgeous close-ups, and slow dollying. It attaches itself effortlessly to the film's dreamlike tone, like two perfect jigsaw pieces. It's a platitude, I know -- but it has to be seen to be believed. If there's any justice in the world, "Long Day's Journey" will be shown in college cinematography classes around the world for decades to come.

The film jumps back and forth from present day to roughly 20 years prior, when our protagonist Luo Hongwu (Huang Jue) was spending time with his since long-lost love, Wan Qiwen (Tang Wei). The cuts that change time periods are not always recognizable, and the overall delivery of the plot is muddled at times. I think that these subtle cuts were an intentional decision by the director, Bi Gan, to preserve a sense of dreamlike continuity that works in favor of the film's tone. Unfortunately, it messed with the overall comprehension of the plot -- at times it was unclear if the action on-screen was supposed to be occuring in present day, or in the past. About 30 minutes into the film, I noticed that Hongwu's facial hair was slightly different depending on the time frame; once I figured this out, the unclear timeline wasn't a huge issue for me. At the same time, I can completely understand why some would be utterly baffled by the film because of this. The two poor people who sat behind me never figured it out, frequently making comments about how confused they were, and I can't blame them.

But at the same time, "Long Day's Journey" isn't truly about the plot. It's about a man's mind, and the feelings of beauty, pain, darkness, and light that comes with the notion of loving someone you should've moved on from a decade ago. In a way, the cinematography and the fantastic score are the true "directors" of the film, and bring these themes to life even more than the plot itself.

The final 55 minutes of the film -- the long cut I mentioned earlier -- is a clear break from the rest of the film; an "epilogue" if you will. It is entirely surreal, perhaps even nonsensical, and heavily alludes to themes and symbolism from the first 90ish minutes...similar to a dream you might have about the day you just lived through. The ending of the film is ambiguous and open to interpretation, like all dreams are. To that end, if I had to describe the entire film in one word, it would certainly be "dreamlike."

This isn't a film for everybody, and that's okay. If you're turned off by nonlinear storytelling, "Long Day's Journey" won't do you any favors; it's not nearly as cohesive and accessible as other films that use the same format. However, I'd reckon that even if you had a difficult time understanding the plot, the overall tone and cinematography will guide you through the rest of the film. If you leave with nothing else, you'll have seen one of the most visually beautiful films of all time.

Take it to the bank, you'll see this film in the running for Best Foreign Film at the Oscars next year.

I first came to hear of this film after reading the extraordinary hype around its cinematography, which features a staggering 55-minute long cut that continues until the end of the film. Let me be abundantly clear that every ounce of this hype is deserved; perhaps even an understatement.

"Long Day's Journey" is quite possibly the most aesthetically beautiful film I've ever seen. If not, it is certainly in the top five. Nearly every single frame of this film looks like it could belong in an art museum. It is shot impeccably, without error, for its entire 133 minute runtime. The cinematographers -- of which there are three -- heavily rely on color contrast, distortion in the shape of oscillating water, gorgeous close-ups, and slow dollying. It attaches itself effortlessly to the film's dreamlike tone, like two perfect jigsaw pieces. It's a platitude, I know -- but it has to be seen to be believed. If there's any justice in the world, "Long Day's Journey" will be shown in college cinematography classes around the world for decades to come.

The film jumps back and forth from present day to roughly 20 years prior, when our protagonist Luo Hongwu (Huang Jue) was spending time with his since long-lost love, Wan Qiwen (Tang Wei). The cuts that change time periods are not always recognizable, and the overall delivery of the plot is muddled at times. I think that these subtle cuts were an intentional decision by the director, Bi Gan, to preserve a sense of dreamlike continuity that works in favor of the film's tone. Unfortunately, it messed with the overall comprehension of the plot -- at times it was unclear if the action on-screen was supposed to be occuring in present day, or in the past. About 30 minutes into the film, I noticed that Hongwu's facial hair was slightly different depending on the time frame; once I figured this out, the unclear timeline wasn't a huge issue for me. At the same time, I can completely understand why some would be utterly baffled by the film because of this. The two poor people who sat behind me never figured it out, frequently making comments about how confused they were, and I can't blame them.

But at the same time, "Long Day's Journey" isn't truly about the plot. It's about a man's mind, and the feelings of beauty, pain, darkness, and light that comes with the notion of loving someone you should've moved on from a decade ago. In a way, the cinematography and the fantastic score are the true "directors" of the film, and bring these themes to life even more than the plot itself.

The final 55 minutes of the film -- the long cut I mentioned earlier -- is a clear break from the rest of the film; an "epilogue" if you will. It is entirely surreal, perhaps even nonsensical, and heavily alludes to themes and symbolism from the first 90ish minutes...similar to a dream you might have about the day you just lived through. The ending of the film is ambiguous and open to interpretation, like all dreams are. To that end, if I had to describe the entire film in one word, it would certainly be "dreamlike."

This isn't a film for everybody, and that's okay. If you're turned off by nonlinear storytelling, "Long Day's Journey" won't do you any favors; it's not nearly as cohesive and accessible as other films that use the same format. However, I'd reckon that even if you had a difficult time understanding the plot, the overall tone and cinematography will guide you through the rest of the film. If you leave with nothing else, you'll have seen one of the most visually beautiful films of all time.

Take it to the bank, you'll see this film in the running for Best Foreign Film at the Oscars next year.

Long Day's Journey Into Night is the love child of Andrei Tarkovsky and Wong Kar-Wai, garnished with a truly insane salad-dressing made up of an unholy mixture of filmmakers such as Peter Greenaway, David Lynch, Guy Maddin, and Leos Carax, playwrights Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter, poet Paul Celan, painters Marc Chagall, Francis Bacon, and Jackson Pollack, and novelists Franz Kafka, Marcel Proust, and Patrick Modiano; not exactly a compendium of the most accessible artists of all time. As unconcerned with formal conventionality as it is with narrative resolution, this is an art-house movie through and through, an esoteric puzzle made up of two distinct parts. Whilst the 2D first half is a measured, but reasonably conventional albeit non-linear noir, the second is composed of an unbroken 50-minute 3D shot that's as aesthetically audacious as it is narratively elliptical. The second feature from 30-year-old self-educated writer/director Bi Gan, Long Day's Journey is aggressively enigmatic, and the absence of character arcs, the formal daring, the languorous pacing, and the resistance to anything approaching definitive conclusions, will undoubtedly see many react with equal parts bafflement and infuriation. However, if you can get past such issues and go with the film on its own terms, you'll find a fascinatingly esoteric examination of the protean nature of memory, a film that in both form and content seems to belie its writer/director's youth and relative inexperience.

Long Day's Journey tells the story of moody loner Luo Hongwu (Jue Huang), a man haunted by his past. In 2000, he met and had a brief but memorable relationship with the mysterious Wan Qiwen (Tang Wei), whom he has never been able to forget. When he returns to his home city of Kaili to bury his father, he sets about trying to track down Qiwen, as the story of their relationship is told via flashbacks. However, it soon becomes apparent that just because Lou remembers a thing doesn't necessarily mean that that thing happened. When his search leads him to a dingy movie theatre, he puts on a pair of 3D glasses and finds himself in an abandoned mine from which his only hope of escape is to win a game of ping pong. The rest of the film takes place in his dream world. Or in the 3D movie playing in the theatre. Or in an amalgamation of both. Or in something else entirely.

Long Day's Journey's biggest selling point is unquestionably the aesthetically audacious second hour. The film starts as a garden variety noir - the world-weary voiceover, the femme fatale revealed through flashbacks, smoke-filled rooms, the back alley meetings, the dangerous gangster, the troubled friend, the darkly fatalistic tone. There's even a clue written on the back of a photo. However, all of these genre markers are jettisoned when Luo enters the cinema, putting on his 3D glasses, just as the audience is prompted to do likewise. The film's title card then appears onscreen for the first time (a full 70 minutes in), and the movie adopts a far more elliptical and esoteric stance than the investigative noir structure of the first half.

Unlike 'single-take' films such as Climax (2018), Utøya 22 juillet (2018), and 1917 (2019), which use long-takes and 'hidden' edits to give the effect of a single-shot, the second half of Long Day's Journey follows films such as L'arche russe (2002) and Victoria (2015) insofar as it was legitimately shot via one single take. And not only that, but it's a complex and visually layered shot too, featuring drones, Steadicams, intricate blocking, elaborate external locations with multitudes of people, practical effects, complex interior locations, even a lengthy sequence set on a zip line. Considering the scope, it would be an impressive enough technological accomplishment in 2D, but that it was filmed with bulky 3D cameras is almost unbelievable, and that three cinematographers worked on the project is unsurprising - Hung-i Yao shot half of the 2D material, Jingsong Dong shot the rest of the 2D material and planned the 3D sequence, whilst David Chizallet actually shot the sequence.

What's especially laudable about the sequence, however, is how it never becomes gimmicky. Most movies released in 3D have no real thematic justification for being in 3D, nothing in their content to justify their form, whilst films such as Victoria have no real thematic justification for being single-shots. Long Day's Journey, however, justifies both decisions - the single-shot works in tandem with the 3D to create a vibrant and complex world of depth and vitality, but one that never seems completely real; there's always the sense of an artifice, something highly 'subjective' getting between the audience and the on-screen images, as if we're not seeing things objectively but instead seeing an individual's interpretation of things - it's reality, but it's mediated reality, with all the subjective distortions that such a thing implies.

This is a film about memory, specifically the idea that memory can be deceptive, and may have as much to do with dreams as with objective reality. In this sequence, as memory, reality, and dream seem to blend into one another, with even identity itself dissolving (several of the main actors re-appear in completely different parts), Gan shows us something that approximates a dream as well as anything you're ever likely to experience, outside actually dreaming. Any film can throw something surreal onscreen and call it a dream scene, but Long Day's Journey manages to convey not just the content of a dream, but the illogical texture of a dream. You replace the 3D images with 2D images, or you replace the single-shot with edited content, and you fundamentally lose that texture; the 3D/single-shot form is as important as James Joyce's removal of punctuation is in creating the impression of a mind on the brink of falling asleep in the last episode of Ulysses (1922) - restore the punctuation, and the interrelatedness of form and content is lost.

Speaking of literature, although the film may seem unrelated to Eugene O'Neill's 1941 play (the Chinese title similarly references a short story collection by Roberto Bolaño), a common theme is memory and the all-consuming power of time. The conventional first half of the film concerns itself not just with memory, but with the imperfect nature of memory, essentially suggesting that obsession is nothing more than a trick of the mind, an attempt to reattain something that may never have existed in the first place (also an important theme in the play). Indeed, it's worth noting that the most recurrent visual motif in the film is that of reflection - not just in mirrors, but so too in puddles, which act as slightly more distorted (subjective?) versions of the relatively perfect reflection one gets from a mirror. So even here, one can see that Gan is examining the distortions of memory and the fault line between objectivity and subjectivity.

All of which will probably go some way to telling you whether or not you're likely to enjoy Long Day's Journey. Make no mistake, this is an esoteric film that isn't especially interested in plot or character, and which uses form to explore complex issues such as memory, subjectivity, and obsession. It's rarely emotionally engaging in a conventional sense and the minimalist plot can result in some rather glib moments. The storyline is elliptical, the characters archetypal, the themes subtle, and, all things considered, the very aspects which one person will find transformative, will completely alienate another. You either embrace the emphasis on mood and tone, or you fight it, trying to find a linear narrative through-line. Personally, I loved its formal daring and admired Gan's confidence and the singularity of his vision, but at the same time, I found each section outstayed it's welcome a little, and felt the first half could lose a good 15 minutes, and the second around 10 or so. Gan also walks a very fine line between emotional detachment and emotional alienation, and it's a line he crosses a couple of times. Nevertheless, this is an awe-inspiring technical achievement, an ultra-rare example of a film which perfectly matches form to content, and a fascinating puzzle that trades in the undefinable nuances of memory. If you have the patience to work with it, the rewards are many.

Long Day's Journey tells the story of moody loner Luo Hongwu (Jue Huang), a man haunted by his past. In 2000, he met and had a brief but memorable relationship with the mysterious Wan Qiwen (Tang Wei), whom he has never been able to forget. When he returns to his home city of Kaili to bury his father, he sets about trying to track down Qiwen, as the story of their relationship is told via flashbacks. However, it soon becomes apparent that just because Lou remembers a thing doesn't necessarily mean that that thing happened. When his search leads him to a dingy movie theatre, he puts on a pair of 3D glasses and finds himself in an abandoned mine from which his only hope of escape is to win a game of ping pong. The rest of the film takes place in his dream world. Or in the 3D movie playing in the theatre. Or in an amalgamation of both. Or in something else entirely.

Long Day's Journey's biggest selling point is unquestionably the aesthetically audacious second hour. The film starts as a garden variety noir - the world-weary voiceover, the femme fatale revealed through flashbacks, smoke-filled rooms, the back alley meetings, the dangerous gangster, the troubled friend, the darkly fatalistic tone. There's even a clue written on the back of a photo. However, all of these genre markers are jettisoned when Luo enters the cinema, putting on his 3D glasses, just as the audience is prompted to do likewise. The film's title card then appears onscreen for the first time (a full 70 minutes in), and the movie adopts a far more elliptical and esoteric stance than the investigative noir structure of the first half.

Unlike 'single-take' films such as Climax (2018), Utøya 22 juillet (2018), and 1917 (2019), which use long-takes and 'hidden' edits to give the effect of a single-shot, the second half of Long Day's Journey follows films such as L'arche russe (2002) and Victoria (2015) insofar as it was legitimately shot via one single take. And not only that, but it's a complex and visually layered shot too, featuring drones, Steadicams, intricate blocking, elaborate external locations with multitudes of people, practical effects, complex interior locations, even a lengthy sequence set on a zip line. Considering the scope, it would be an impressive enough technological accomplishment in 2D, but that it was filmed with bulky 3D cameras is almost unbelievable, and that three cinematographers worked on the project is unsurprising - Hung-i Yao shot half of the 2D material, Jingsong Dong shot the rest of the 2D material and planned the 3D sequence, whilst David Chizallet actually shot the sequence.

What's especially laudable about the sequence, however, is how it never becomes gimmicky. Most movies released in 3D have no real thematic justification for being in 3D, nothing in their content to justify their form, whilst films such as Victoria have no real thematic justification for being single-shots. Long Day's Journey, however, justifies both decisions - the single-shot works in tandem with the 3D to create a vibrant and complex world of depth and vitality, but one that never seems completely real; there's always the sense of an artifice, something highly 'subjective' getting between the audience and the on-screen images, as if we're not seeing things objectively but instead seeing an individual's interpretation of things - it's reality, but it's mediated reality, with all the subjective distortions that such a thing implies.

This is a film about memory, specifically the idea that memory can be deceptive, and may have as much to do with dreams as with objective reality. In this sequence, as memory, reality, and dream seem to blend into one another, with even identity itself dissolving (several of the main actors re-appear in completely different parts), Gan shows us something that approximates a dream as well as anything you're ever likely to experience, outside actually dreaming. Any film can throw something surreal onscreen and call it a dream scene, but Long Day's Journey manages to convey not just the content of a dream, but the illogical texture of a dream. You replace the 3D images with 2D images, or you replace the single-shot with edited content, and you fundamentally lose that texture; the 3D/single-shot form is as important as James Joyce's removal of punctuation is in creating the impression of a mind on the brink of falling asleep in the last episode of Ulysses (1922) - restore the punctuation, and the interrelatedness of form and content is lost.

Speaking of literature, although the film may seem unrelated to Eugene O'Neill's 1941 play (the Chinese title similarly references a short story collection by Roberto Bolaño), a common theme is memory and the all-consuming power of time. The conventional first half of the film concerns itself not just with memory, but with the imperfect nature of memory, essentially suggesting that obsession is nothing more than a trick of the mind, an attempt to reattain something that may never have existed in the first place (also an important theme in the play). Indeed, it's worth noting that the most recurrent visual motif in the film is that of reflection - not just in mirrors, but so too in puddles, which act as slightly more distorted (subjective?) versions of the relatively perfect reflection one gets from a mirror. So even here, one can see that Gan is examining the distortions of memory and the fault line between objectivity and subjectivity.

All of which will probably go some way to telling you whether or not you're likely to enjoy Long Day's Journey. Make no mistake, this is an esoteric film that isn't especially interested in plot or character, and which uses form to explore complex issues such as memory, subjectivity, and obsession. It's rarely emotionally engaging in a conventional sense and the minimalist plot can result in some rather glib moments. The storyline is elliptical, the characters archetypal, the themes subtle, and, all things considered, the very aspects which one person will find transformative, will completely alienate another. You either embrace the emphasis on mood and tone, or you fight it, trying to find a linear narrative through-line. Personally, I loved its formal daring and admired Gan's confidence and the singularity of his vision, but at the same time, I found each section outstayed it's welcome a little, and felt the first half could lose a good 15 minutes, and the second around 10 or so. Gan also walks a very fine line between emotional detachment and emotional alienation, and it's a line he crosses a couple of times. Nevertheless, this is an awe-inspiring technical achievement, an ultra-rare example of a film which perfectly matches form to content, and a fascinating puzzle that trades in the undefinable nuances of memory. If you have the patience to work with it, the rewards are many.

I had a hard time following the first half of the movie, it felt more like shattered memories than cohesive story/narrative. It felt to long although it had it's moments like the karaoke part... Then that one hour long take came and it blew me away. The camerawork and visuals in this movie are astonishing, it added to that hypnotizing feeling of the whole movie. With few rewatched the rating might go up!

"Long Day's Journey Into Night," alternatively known as "Last Evenings on Earth," indeed, is a bewildering movie. Partially, I consider it even a mind-game, or puzzle, picture, as defined by the likes of Thomas Elsaesser. Yet, while there are other avenues through which to interpret it all, and there are some other, fine reviews that do just that, the main means by which I came to grips with Bi Gan's enigmatic tour de force is by way of Alfred Hitchcock's "Vertigo" (1958). Most movies are memories of other movies to a large extent, with the originality being in the re-arrangement, or remembrance, of the former one. Even many supposedly "revolutionary" reels are such in the original sense of the word of returning to a prior place. Undoubtedly, there are other demonstrable influences here, which others have mentioned, including the films of Andrei Tarkovsky and Wong Kar-wai, and there's also the emphasis on the green book doubling the picture's alternate titles that recall the prose of Eugene O'Neill's play and a short story by Roberto Bolaño. Perhaps, if not surely, due to my greater familiarity with Hitchcock's film than with some of those other benchmarks, the prominent references to "Vertigo," however, especially stand out here. Most blatant of these are the woman's green dress and the much-imitated revolving "Vertigo" kiss near the end. More vitally, this reflexivity aids in making sense of the picture.

"Vertigo" is a more accessible and mainstream film that has been around for a long time, infinitely analyzed and so is seemingly easier to decipher. It's a stolen love story, as is the stolen green book here, as is "Long Day's Journey Into Night," despite the supposed deception of its marketing campaign that brought in the lion's share of its box office. Both are shadowy noir (reinforced by the voiceover narration here) in vibrant color where the detective protagonist searches for, to reclaim, that past, lost and stolen love. He is thrust into a vertiginous maze of spinning doppelgängers, dreams, ghosts, memories, time and regrets. Hitchcock's hero literally experienced debilitating vertigo, as well as a psychotic break, amid the rolling hills of San Francisco and up the bell tower; whereas in Bi's picture, the green book's spell is said to make the room spin and spinning a ping-pong paddle makes one fly over the labyrinths of staircases and mineshafts of Guizhou province where the hero here follows in circles redoubled ghosts and women.

As with "Vertigo," too, this one is split into two parts. In the first part, for both of them, the detective shadows the woman, or femme fatale, and investigates the mystery at hand. More so with Hitchcock's camera, but here, too, this is largely composed of the system of looks Laura Mulvey termed the "male gaze." With Hitchcock, this took the form of shots/countershots--i.e. shot of man looking followed by shot of woman he's looking at. Bi doesn't work in the tradition of classical continuity editing to emerge from Hollywood back in the 1910s and which largely continues to this day, though. His, one might say, international art-house style is of a slow cinema (I would agree oft too slow--that elevator lift sequence where the camera operator blatantly waits for his seat to track the character down especially tries the spectator's patience), where mise-en-scène takes prominence over montage. In lieu of edited scene dissection, however, there is camera movement, as well as the role of the camera in shifting between a neutral observer and a shared perspective with a character--almost always the male protagonist. Hence, we see shots of women where the man's presence is acknowledged as off-screen, out of frame, sharing his and the camera's gaze with the spectator. Frequently, these views are photographed through glass, mirrors and puddle reflections, to reinforce the voyeurism and the intentionally artificial perspective as seen through one character and the camera's lens.

This first part is fragmented, non-linear and, here, as based on memories as rusty as the otherwise perplexing views in the movie of rust and damp and dilapidated structures. Clocks are broken. Rain drops. Makeup smeared. Trains stopped by the dislodging of mudslides. Earth mined out. A glass falling off the table to shatter into pieces. Perhaps, this reflects the chaptered, at the reader's own pace, nature of written stories and even told ones, remembered as they are--many characters telling each other stories or stories about being told stories in this one. Thus, the focus on the green book, as well as the photographic snapshot hidden within a broken clock, in the first part. In "Vertigo," too, there was the art of painting, the appreciation by one of the women (Judy) and the designing of by the other (Midge). In both pictures, then, they move from watching, from voyeurism--that is, from our position as spectator--to filmmaking itself in their second parts.

The break in "Long Day's Journey Into Night" is even greater than the nightmare of "Vertigo," with the putting on of the glasses for its virtuoso 59-minute one-shot in 3D and the delayed reveal of the title. This is the Buster Keaton in "Sherlock Jr." (1924) moment (or is it the reverse of "The Purple Rose of Cairo" (1985)?), where he enters the movie of the cinema he's sitting in, watching and dreaming, recalling past movies and other artworks as we should've been following along with, too, throughout. It's where extraordinary planning and nimbleness in tracking with the bulky 3D camera meets the dolly-out combined with zoom-ins of the "Vertigo" effect shots, along with its dream sequence visuals and even those dated rear-projection process shots. Showy, sure, even, perhaps, distracting, but the effects have their functions. Motion pictures depict time like no other art form. It may be cut up (as in "Vertigo"), fragmented beyond the point of normal narrative (the first part here), and presented in real time. Characters continually followed and reappearing (including that humorous donkey), mazes unraveled, the past revealed in cinematic ghosts and the doppelgänger characters of the already reproduced images of motion pictures. Karaoke kept on track by pre-recorded music. "Vertigo" kiss. A firework marking the passing of time.

I'm not quite sure this is a great movie so much as it's a great mystery story--perhaps, such distinction is needless. I mean, the cinematography is some of the best in recent memory, but the deconstruction of its function and that of the narrative itself seems far more rewarding than any mystery therein. It's hard to say that anything meaningful comes from the realization of the child as a ghost from a past murder, the mother and the femme fatale, or the woman of his dreams reappearing, let alone whether what the protagonist experiences is dream or reality. "Mind-game films," for which such checks several boxes, weren't a theoreticized genre in Hitchcock's day. There's hardly any of the psychosexual pervsity found underneath "Vertigo" here, Mulvey's psychoanalytic junk regarding castration anxiety and all included (the limbs of Jimmy Stewart broken were never as vital to the story as they were as metaphor). Hitchcock's film was a mature work, recalling memories of his past features (namely, "Rear Window" (1954)), whereby he reconstructed those dreams and remembrances, remaking his trademarks such as the Hitchcock blonde in the process. Never bravado for its own sake. Nary an obscure reference necessitating shared eclectic tastes. Little lingering to force confronting the confusion of the picture's lack.

Nevertheless, to say "Long Day's Journey Into Night" doesn't rise to the level of "Vertigo" is a slight criticism, indeed. It remains a picture of many levels to appreciate. Even if sense can't be made of it, there are beautiful compositions and motifs, staggering craft and intelligent themes to admire. The destination doesn't so much matter, except that it's exquisite, too, for the journey is what's important. Not so much what was or will be--paying much head to the story here seems an errant errand--but how, including the cinematic reflexivity, one remembers and dreams.

"Vertigo" is a more accessible and mainstream film that has been around for a long time, infinitely analyzed and so is seemingly easier to decipher. It's a stolen love story, as is the stolen green book here, as is "Long Day's Journey Into Night," despite the supposed deception of its marketing campaign that brought in the lion's share of its box office. Both are shadowy noir (reinforced by the voiceover narration here) in vibrant color where the detective protagonist searches for, to reclaim, that past, lost and stolen love. He is thrust into a vertiginous maze of spinning doppelgängers, dreams, ghosts, memories, time and regrets. Hitchcock's hero literally experienced debilitating vertigo, as well as a psychotic break, amid the rolling hills of San Francisco and up the bell tower; whereas in Bi's picture, the green book's spell is said to make the room spin and spinning a ping-pong paddle makes one fly over the labyrinths of staircases and mineshafts of Guizhou province where the hero here follows in circles redoubled ghosts and women.

As with "Vertigo," too, this one is split into two parts. In the first part, for both of them, the detective shadows the woman, or femme fatale, and investigates the mystery at hand. More so with Hitchcock's camera, but here, too, this is largely composed of the system of looks Laura Mulvey termed the "male gaze." With Hitchcock, this took the form of shots/countershots--i.e. shot of man looking followed by shot of woman he's looking at. Bi doesn't work in the tradition of classical continuity editing to emerge from Hollywood back in the 1910s and which largely continues to this day, though. His, one might say, international art-house style is of a slow cinema (I would agree oft too slow--that elevator lift sequence where the camera operator blatantly waits for his seat to track the character down especially tries the spectator's patience), where mise-en-scène takes prominence over montage. In lieu of edited scene dissection, however, there is camera movement, as well as the role of the camera in shifting between a neutral observer and a shared perspective with a character--almost always the male protagonist. Hence, we see shots of women where the man's presence is acknowledged as off-screen, out of frame, sharing his and the camera's gaze with the spectator. Frequently, these views are photographed through glass, mirrors and puddle reflections, to reinforce the voyeurism and the intentionally artificial perspective as seen through one character and the camera's lens.

This first part is fragmented, non-linear and, here, as based on memories as rusty as the otherwise perplexing views in the movie of rust and damp and dilapidated structures. Clocks are broken. Rain drops. Makeup smeared. Trains stopped by the dislodging of mudslides. Earth mined out. A glass falling off the table to shatter into pieces. Perhaps, this reflects the chaptered, at the reader's own pace, nature of written stories and even told ones, remembered as they are--many characters telling each other stories or stories about being told stories in this one. Thus, the focus on the green book, as well as the photographic snapshot hidden within a broken clock, in the first part. In "Vertigo," too, there was the art of painting, the appreciation by one of the women (Judy) and the designing of by the other (Midge). In both pictures, then, they move from watching, from voyeurism--that is, from our position as spectator--to filmmaking itself in their second parts.

The break in "Long Day's Journey Into Night" is even greater than the nightmare of "Vertigo," with the putting on of the glasses for its virtuoso 59-minute one-shot in 3D and the delayed reveal of the title. This is the Buster Keaton in "Sherlock Jr." (1924) moment (or is it the reverse of "The Purple Rose of Cairo" (1985)?), where he enters the movie of the cinema he's sitting in, watching and dreaming, recalling past movies and other artworks as we should've been following along with, too, throughout. It's where extraordinary planning and nimbleness in tracking with the bulky 3D camera meets the dolly-out combined with zoom-ins of the "Vertigo" effect shots, along with its dream sequence visuals and even those dated rear-projection process shots. Showy, sure, even, perhaps, distracting, but the effects have their functions. Motion pictures depict time like no other art form. It may be cut up (as in "Vertigo"), fragmented beyond the point of normal narrative (the first part here), and presented in real time. Characters continually followed and reappearing (including that humorous donkey), mazes unraveled, the past revealed in cinematic ghosts and the doppelgänger characters of the already reproduced images of motion pictures. Karaoke kept on track by pre-recorded music. "Vertigo" kiss. A firework marking the passing of time.

I'm not quite sure this is a great movie so much as it's a great mystery story--perhaps, such distinction is needless. I mean, the cinematography is some of the best in recent memory, but the deconstruction of its function and that of the narrative itself seems far more rewarding than any mystery therein. It's hard to say that anything meaningful comes from the realization of the child as a ghost from a past murder, the mother and the femme fatale, or the woman of his dreams reappearing, let alone whether what the protagonist experiences is dream or reality. "Mind-game films," for which such checks several boxes, weren't a theoreticized genre in Hitchcock's day. There's hardly any of the psychosexual pervsity found underneath "Vertigo" here, Mulvey's psychoanalytic junk regarding castration anxiety and all included (the limbs of Jimmy Stewart broken were never as vital to the story as they were as metaphor). Hitchcock's film was a mature work, recalling memories of his past features (namely, "Rear Window" (1954)), whereby he reconstructed those dreams and remembrances, remaking his trademarks such as the Hitchcock blonde in the process. Never bravado for its own sake. Nary an obscure reference necessitating shared eclectic tastes. Little lingering to force confronting the confusion of the picture's lack.

Nevertheless, to say "Long Day's Journey Into Night" doesn't rise to the level of "Vertigo" is a slight criticism, indeed. It remains a picture of many levels to appreciate. Even if sense can't be made of it, there are beautiful compositions and motifs, staggering craft and intelligent themes to admire. The destination doesn't so much matter, except that it's exquisite, too, for the journey is what's important. Not so much what was or will be--paying much head to the story here seems an errant errand--but how, including the cinematic reflexivity, one remembers and dreams.

Did you know

- TriviaThe marketing of the film was met with major controversy after its opening. The marketing of this art film was targeted massively towards the general public, instead of art film lovers. The film opened on December 31, 2018 since it was the last day of the year and it was intended to be "a good event to celebrate the new year". It was estimated that a lot of people went to see the film without knowing that this is an art house film. This resulted in major backlash as netizens complained against the film, as well as calling the ones who appreciated it "jia wenyi (phony-artistic)". The film earned 38 million USD on the first day of opening, yet the box office of the second day was decreased by 96%.

- ConnectionsReferenced in AniMat's Crazy Cartoon Cast: The End of that Stupid Hashtag (2020)

- How long is Long Day's Journey Into Night?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Release date

- Countries of origin

- Official sites

- Languages

- Also known as

- Long Day's Journey Into Night

- Filming locations

- Production companies

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Box office

- Budget

- CN¥40,000,000 (estimated)

- Gross US & Canada

- $521,365

- Opening weekend US & Canada

- $26,746

- Apr 14, 2019

- Gross worldwide

- $42,140,994

- Runtime2 hours 18 minutes

- Color

- Aspect ratio

- 1.85 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content

![Watch Trailer [IT]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/M/MV5BMDUzOGJjMTAtMGE1Zi00Y2JlLWEzMWItZTJiYjY2M2I4NDVlXkEyXkFqcGdeQXRyYW5zY29kZS13b3JrZmxvdw@@._V1_QL75_UX500_CR0)