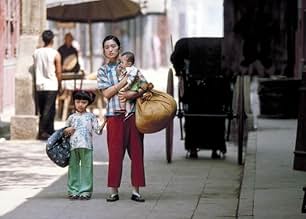

Depois que Fugui e Jiazhen perdem suas fortunas pessoais, eles formam uma família e sobreviveram às difíceis mudanças culturais entre as décadas de 1940 a 1970, na China.Depois que Fugui e Jiazhen perdem suas fortunas pessoais, eles formam uma família e sobreviveram às difíceis mudanças culturais entre as décadas de 1940 a 1970, na China.Depois que Fugui e Jiazhen perdem suas fortunas pessoais, eles formam uma família e sobreviveram às difíceis mudanças culturais entre as décadas de 1940 a 1970, na China.

- Ganhou 1 prêmio BAFTA

- 5 vitórias e 6 indicações no total

Avaliações em destaque

Lantern was precisely contained within narrative walls, it abstracted life by placing us in the midst of turning cycles of life and wove cloths out of that turning in the form of rituals that marked passage; color, sound, weather, architecture. It was akin to a Buddhist mandala to me, a cosmic picture directing me to find my own place in the center of things, choose repose over madness.

Zhang by contrast here wanders unconstrained, under the auspice of history, aiming for a full chronicle of sorts of Chinese life as a family moves through the decades. The stage backdrop changes frequently; Civil war, Great Leap, Cultural Revolution.

We do still have the turning of cycles and it does create a (cosmic) picture; a life of comfort squandered by the man's ignorance who loses it all, to one of hardship and quiet abiding. But eventually it doesn't direct towards a center that will illuminate the turn as something more than the ramblings of history.

And it's simply not a very enviable position to want to be the chronicler of history like Zhang is trying to here, it reminds me of how Kusturica stifled himself in similar endeavors. It means our reference point always has to be an externally agreed version of reality and we have to be chained to that sweep.

You can see him try to root himself in something more essential - the husband becomes a puppeteer putting on shadow plays for the people, life as the canvas where these evanescent shadow plays are enacted, now losing a fortune, now gaining back your family, so that we could see it from the distance of transient flickers of drama. Civil war is introduced as someone hacking down the screen, revealing war as another play that demands its actors assume their place.

But this is forgotten in lieu of stopping at various points of history so that it ends up being more the Oscar winning type than history parting to reveal myriad reflections like Andrei Rublev. Had it come out from the West, I'm sure it would have won a few and the wonderful Gong Li her first. The best I got out of it eventually was the sense of a man and woman trying to make their way together as the skies shift and the stage quakes by the ignorance of unseen puppet masters enacting their little plays. The Great Leap castigated as a wall collapsing on a little boy, because the man who crashed his car and the boy were both overworked and needed sleep.

Zhang took care to color history within certain lines so that we veer close to the monumental failures of the era but never quite see the full brunt of the horror, famine or mass persecution, only bits of abuse in passing. It was still banned by Party hacks anxious to control the play.

What I think Zhang Yimou's message here is that the will of the people "to live," as in the title, to survive and overcome obstacles is what defines the Chinese people. They ride the ox of communism as a boat rides a wave. They adapt.

Consider that tall and thin Fugui (played with consummate skill by You Ge) says that a chick will become a chicken when it grows up, and then a sheep and then an ox and then the Communist Party. But as the film ends he tells his grandson only that the chick will become a chicken and then a sheep and then an ox. He doesn't mention communism. In this way we know that the people have tamed the ox.

Zhang's film is an epic parable of life in China in the 20th century. It opens before the communist revolution with protagonist Fugui as a wayward son who is gambling the family fortune away. His wife, Jiazhen (Gong Li) pleads with him to stop, but he cannot. He is addicted to vice. Symbolically he represents the old regime. He loses everything, wife included and goes to live in the streets. After some time the revolutionary war begins and he and his friends find it convenient to switch sides and join the revolutionary army--he as an entertainer for the troops, a puppeteer. He and wife reunite and become loyal and even enthusiastic communists. He is lucky to have lost his fortune for now he is recognized as a hero of the revolution, while the man who won his family's house at dice is declared a counter-revolutionary and meets a bad end.

As in every Zhang Yimou film I have seen, everything is beautifully and exquisitely done. His work is characterized by an artist's sense of color and form, by an engaging simplicity in the telling, and by a subtle sense of what is going on politically, and especially by a deep and abiding sense of humanity. Here the transformation of Chinese society from feudalism to communism to the capitalist/communism hybrid that exists today is shown through the eyes and experiences of the people; and what is emphasized is the endurance and the will of the people to survive, adapt and finally to flourish regardless of who might be in power.

I would compare Zhang Yimou to the very greatest directors, say, to Stanley Kubrick, to Francis Ford Coppola, to Louis Malle, to Krzysztof Kieslowski in sheer artistic talent. Like Malle he is warm and honest about human beings and what they do without being maudlin or sentimental. Like Coppola he has an epic-maker's vision, and like the Coppola of the Godfather films, a strong sense of family. Like Kubrick he is creative and always aware of the needs of the audience, and like Kieslowski he is clever.

This is in some respects Zhang Yimou's finest achievement because of the way he tells the story of communism in China. I am reminded of the way Louis Malle tells the truth about human sexuality without inciting the censors. Here Zhang Yimou tells the truth about the communist experience in China, subtly demonstrating its cruelties and stupidities without, amazing enough, incurring the wrath of the authorities. (Some of his films have been banned in China, but I understand they are readily available nonetheless.) Here the kids are smiling and happy as they work in the steel mill. The accident that kills Fugui's son is seen as just that, an accident and not the fault of the "Great Leap Forward." The members of the educated class, who are ridiculed, beaten and banished (and worse) during the "Cultural Revolution," accept their fate as their just deserts--the doctor who insists that it is better to wear the placard shaming him that is hung from around his neck than it is to take it off. The local official who has preached and practiced the communist line faithfully, who finds himself being labeled a capitalist, also accepts his fate as though in doing so he is furthering a cause larger than himself.

In a way Zhang Yimou's international celebrity and reputation as one of the world's greatest film makers protects him. In another sense his depictions of the sins and excesses of the old regime before communism are so well done and appreciated by all, that such an expression also protects him.

Nonetheless, I do not personally consider this Zhang Yimou's best film. I prefer the startling beauty of Raise the Red Lantern (1991) and Red Sorghum (1987) as well as the charming Not One Less (1999) or the simple but powerful, The Story of Qiu Ju. However, this is an outstanding film.

Notable in a supporting role is Wu Jiang as Wan Erxi the strong young man with the limp who marries the mute daughter. I have seen him in Shower (1999) in which his personal charisma and strength of character are shown more fully. He is the younger brother of Wan Jiang who starred in Zhang Yimou's first film, Red Sorghum. Of course Gong Li, one of the finest actresses of our time, who is often featured in Zhang Yimou's films, is outstanding as always.

(Note: Over 500 of my movie reviews are now available in my book "Cut to the Chaise Lounge or I Can't Believe I Swallowed the Remote!" Get it at Amazon!)

It is easy to dismiss this movie as a "Sad period piece," but with another look, one sees that this is a story about triumph... of taking heart in the fact that one lives. The title, "To Live," is very apt, as we see the rises and falls of one small family living through the ups and downs of China during the pre-revolutionary era, the civil war, the Great Leap Forward, the Proletariat Cultural Revolution, and beyond.

This movie is at turns dramatic, humorous, touching, chilling, heart-wrenching, and triumphant. A true roller coaster of emotions, played out in the subtle tones only Chinese film can truly capture.

I watched this movie because it had won the top award at Cannes. I hadn't high hopes for some reason, but I figured it was worth a look. I am very glad I did because it is a wonderful little piece that can be enjoyed with little knowledge of the regime against which it is set. The story follows the family's misfortunes and how they are affected by the rise of Chairman Mao. Their plight is touching as they suffer wrongs but also show compassion on others all the while trying to do the right thing by the system that is impacting on them. Even when tragedy occurs they never blame Communism but heap it on themselves instead.

This unfolds over many years with the rise of Mao as the backdrop. The parrellel between the two things is clear without being forced or rammed down our throats it's a wonderful bit of handling. Even better is the infusion of comic touches all the way through, the dialogue (even in subtitle form) is great and is witty and touching I laughed out loud many times.

Not having seen any other films by Zhang, I can only hope they are as good as this one. The cast, too, do a great job with the film. You Ge's Fugui is fabulous he is a draw from the start on, and his ageing is so convincing that credit must go not only to the makeup but also to Ge for doing so well with potentially tragic figure. Likewise Gong is superb but ages less convincingly. The support cast are all good from the children through to the figures of Mao like Jiang and Niu. The only thing that saddened me about the two great leads is to think that Western cinema will never care to have them in any films I guess that when it comes to Hong Kong cinema Hollywood only are interested if it has slow-motion and guns! (and they think they're cutting edge!)

Overall I find it very hard to fault this film as it has so much going for it on so many levels. Just as a human story it is excellent, and the historical context only serves to make it better. Comic and touching right to it's perfectly pitched close, this should be searched out by anyone who wants a genuinely moving human tale with political comment sown into each frame without intrusion.

Both leading actors nicely portray the way their characters change over the years. At first, Fugui is the stereotypical "callow young man" and Jiazhen the even more stereotypical "long- suffering wife," but the screenplay and actors eventually deepen the characterizations.

The best sequence of the film covers the Chinese Civil War. Wisely, Yimou Zhang resists the temptation to make the movie too epic, and instead focuses on Fugui's personal experiences. The result is a very moving depiction of the human cost of war. In another striking touch, Fugui's hobby is singing with a shadow-puppet troupe. The puppets not only provide an interesting glimpse into traditional Chinese culture, they also take on a symbolic meaning.

After watching "To Live," it's easy to see why the Chinese authorities banned it: there's a lot of tragedy in the film, and in most cases, Communism is to blame. Remarkably, though, Zhang also makes many of the Communist characters sympathetic. For instance, Fugui and Jiazhen's daughter marries an officer in the Red Guards, who is a little ridiculous in his devotion to Mao Zedong, but not a villain. This is in keeping with the overall spirit of "To Live"--humanistic and subtle, instead of bombastic or propagandistic. It's both an important examination of recent Chinese history, and a universal story about how individual human beings manage "to live" in times of hardship. A rare combination, and one well worth seeing.

Você sabia?

- CuriosidadesInitially, Director Zhang Yimou was forbidden from filmmaking for 5 years by the Chinese Communist Party as a result of making this film. However, due to outside pressure this was later withdrawn.

- Citações

Little Bun: [playing with chickens] When will they grow up?

Xu Jiazhen: Very soon.

Little Bun: And then?

Xu Fugui: And then... the chickens will turn into geese... and the geese will turn into sheep... and the sheep will turn into oxen.

Little Bun: And after the oxen?

Xu Fugui: After oxen...

Xu Jiazhen: After oxen, Little Bun will grow up.

Little Bun: I want to ride on an ox's back.

Xu Jiazhen: You will ride on an ox's back.

Xu Fugui: Little Bun won't ride on an ox... he'll ride trains and planes... and life will get better and better.

Principais escolhas

- How long is To Live?Fornecido pela Alexa

Detalhes

Bilheteria

- Faturamento bruto nos EUA e Canadá

- US$ 2.332.728

- Fim de semana de estreia nos EUA e Canadá

- US$ 32.900

- 20 de nov. de 1994

- Faturamento bruto mundial

- US$ 2.332.728

- Tempo de duração2 horas 13 minutos

- Cor

- Mixagem de som

- Proporção

- 1.85 : 1

Contribua para esta página