AVALIAÇÃO DA IMDb

7,6/10

7,2 mil

SUA AVALIAÇÃO

Adicionar um enredo no seu idiomaA lonely barfly falls in love with a married bar singer.A lonely barfly falls in love with a married bar singer.A lonely barfly falls in love with a married bar singer.

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Artistas

- Prêmios

- 2 vitórias e 1 indicação no total

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Elenco e equipe completos

- Produção, bilheteria e muito mais no IMDbPro

Avaliações em destaque

Okay, so my ongoing project is that I'm seeking out films where as you watch the self who sees comes into focus. The most clear and direct way is with slow filmmakers like Tarr and others, though it's a lost game if you let them simply numb you. Others like Greenaway, Lynch and Ruiz will do it by tricking you into invented realities, another boat down the same river.

Usually there's some impatience, a trying to figure things out, a disorientation is central among these filmmakers as the first step. As you quiet down that impatient self, and films of this sort help, things become clearer, unusual insights appear. But it also helps to see past the filmmaker, most of the time he imposes on his created world by trying to explain (usually through a surrogate self) some part of it, reducing.

Also clear, in this case it's the protagonist philosophizing on meaningless life, impossible salvation and the ruin of having to be, dreary stuff. Because he is the protagonist, we think some of it will shed some light. But that's just who Tarr is, gloomy, wondering. I don't doubt his sincere despair. But what's the use? Rest there and he'll suffocate you, stain you without cleansing.

Anyway, discard all that, and it can be a different experience. It's a worthy film beneath the mud.

It's a simple story, a schmuck is contracted to smuggle in a parcel, we can assume by the secrecy that it's some shady deal. In turn he contracts the husband of a woman he's having an affair with—a sexy torch singer. As the husband goes away, we go on to visit disconnected stops in this affair, this is what gives the film its dreamlike air. So that's the story.

More interesting is the world behind it. Your clue is a recurring visual motif introduced with just the first shot—a hazy view of something, and pan to reveal someone watching, an intermediate self between you and things. He IS constantly obscuring the view by thinking what it's about. The second time it's like in a film noir, it's raining, a man is watching a bar. Inside the bar, we are seduced by the femme fatale's smoky song, maybe it's all a nightmare as the lyrics say.

It's a wonderful scene that sets everything else up.

So as per noir rules, desire fools with the schmuck's sense of reality and we have the rest of the film as hazy perturbation. He has done something wrong and knows it, sending the husband away. The third time the watcher motif appears, the woman is not looking out to life through the blinds, but inside the room, her gaze cramped by walls of his desire —the scene plays out with sex, mirrored in a mirror reinforcing inversed reality.

So the affair grows stale—and lo, we have his endless monologues rationalizing frustration by directing it to the world, the world as punishment. And that as profundity that distracts.

So who is obscuring the view?

It's that intermediate self who instead of seeing, fidgets for more story and answers that preferably make some sense. It's your own self, fidgeting for more story when you watch a film like this.

Isn't this something that actually happens? As you watch these ultra slow films, which is why they can help, doesn't your own fidgety self distract you by aimless thinking? Isn't that self getting in the way of what is potentially there for you? Imagine if Tarr acknowledged the fact in his narration, for instance like Nabokov does with self-deprecating layered humor—it'd be an astounding film.

Tarr has set up other cool things, the husband knowing something is wrong as our guy's guilt, an older woman (his woman) suggesting peace in the dance together. But there are moments like when she quotes the Bible and the inane end with the dog, which muddle what it is about. Tarr was probably unsure himself, the interested part of him doing the noir abstraction, another part of him venting.

But the scene at the bar, her song as noir hallucination. The architecture and roaming camera as in Marienbad. And all of it submerged as different levels of watching. I'd like to think Lynch saw this, and immediately knew which parts worked. Tarr is probably still unsure.

Usually there's some impatience, a trying to figure things out, a disorientation is central among these filmmakers as the first step. As you quiet down that impatient self, and films of this sort help, things become clearer, unusual insights appear. But it also helps to see past the filmmaker, most of the time he imposes on his created world by trying to explain (usually through a surrogate self) some part of it, reducing.

Also clear, in this case it's the protagonist philosophizing on meaningless life, impossible salvation and the ruin of having to be, dreary stuff. Because he is the protagonist, we think some of it will shed some light. But that's just who Tarr is, gloomy, wondering. I don't doubt his sincere despair. But what's the use? Rest there and he'll suffocate you, stain you without cleansing.

Anyway, discard all that, and it can be a different experience. It's a worthy film beneath the mud.

It's a simple story, a schmuck is contracted to smuggle in a parcel, we can assume by the secrecy that it's some shady deal. In turn he contracts the husband of a woman he's having an affair with—a sexy torch singer. As the husband goes away, we go on to visit disconnected stops in this affair, this is what gives the film its dreamlike air. So that's the story.

More interesting is the world behind it. Your clue is a recurring visual motif introduced with just the first shot—a hazy view of something, and pan to reveal someone watching, an intermediate self between you and things. He IS constantly obscuring the view by thinking what it's about. The second time it's like in a film noir, it's raining, a man is watching a bar. Inside the bar, we are seduced by the femme fatale's smoky song, maybe it's all a nightmare as the lyrics say.

It's a wonderful scene that sets everything else up.

So as per noir rules, desire fools with the schmuck's sense of reality and we have the rest of the film as hazy perturbation. He has done something wrong and knows it, sending the husband away. The third time the watcher motif appears, the woman is not looking out to life through the blinds, but inside the room, her gaze cramped by walls of his desire —the scene plays out with sex, mirrored in a mirror reinforcing inversed reality.

So the affair grows stale—and lo, we have his endless monologues rationalizing frustration by directing it to the world, the world as punishment. And that as profundity that distracts.

So who is obscuring the view?

It's that intermediate self who instead of seeing, fidgets for more story and answers that preferably make some sense. It's your own self, fidgeting for more story when you watch a film like this.

Isn't this something that actually happens? As you watch these ultra slow films, which is why they can help, doesn't your own fidgety self distract you by aimless thinking? Isn't that self getting in the way of what is potentially there for you? Imagine if Tarr acknowledged the fact in his narration, for instance like Nabokov does with self-deprecating layered humor—it'd be an astounding film.

Tarr has set up other cool things, the husband knowing something is wrong as our guy's guilt, an older woman (his woman) suggesting peace in the dance together. But there are moments like when she quotes the Bible and the inane end with the dog, which muddle what it is about. Tarr was probably unsure himself, the interested part of him doing the noir abstraction, another part of him venting.

But the scene at the bar, her song as noir hallucination. The architecture and roaming camera as in Marienbad. And all of it submerged as different levels of watching. I'd like to think Lynch saw this, and immediately knew which parts worked. Tarr is probably still unsure.

An exceptionally brilliant movie. But this is not for everyone. Beautifully shot in black and white, the director bravely specialises in spectacularly lengthy shots which the viewer's brain will either become absorbed by or reject for tedium. An interesting dimension which can heighten involvement in these long shots (or annoy the hell out the unconvinced) is rhythmical sound - be it cranky machinery (like the relentless mechanical pulley system outside the 'central' character's window) or people dancing to cabaret music. There is a detachment to the camera-work, particularly in the dance band sequences, which reminded me of Kubrick. Again this is an approach which will alienate many viewers but it lends a kind of philosophical power what would otherwise be mundane documentary social observation.

I watched this after the more recent Werckmeister Harmonies on the current double-disc DVD edition available in the UK which is a superb issue and has an interview with the Director as a bonus feature. Interesting to note that he states quite categorically that he intends no allegorical/symbolic element to his work.

I watched this after the more recent Werckmeister Harmonies on the current double-disc DVD edition available in the UK which is a superb issue and has an interview with the Director as a bonus feature. Interesting to note that he states quite categorically that he intends no allegorical/symbolic element to his work.

Yes, this is not for every movie goer. But it rewards those who love the art of film making. Very stylized, yes, but directed by someone who has chosen film as his medium for expresses and articulating a world view that is bleak, atheistic and unforgiving. You may not "like" this film: but as an antidote to all that is superficial, crass and commercial it is terrific. To some, it is intellectual masturbation: to those who see film as an art form, a movie to be admired, debated and savored. It will be seen by fewer than those who enter any "Blockbuster" video store on any given day- but, God help me, I would rather see this film than any other at that store.

Damnation was one of those rare instances when I felt both frustrated and fascinated by the film I was watching. Bela Tarr is SO adept at creating mood that the light sketches of plot began to feel superfluous, and I found myself wanting to brush them away and just float in this surreal sludge without trying to follow a 'story'. Tarr's use of sound design and music to create tension and a dream-like state come closer to David Lynch's than anything else I've seen. The original (I'm assuming) songs in the film also share that distinctive quality of mimicking a certain genre of familiar music, while having something that's a bit off about them - much like Badalamenti's scores. Interesting to note that Blue Velvet was released two years prior. The slowly gliding camera, which seems to have almost it's own agenda aside from the film ads to the purveying sensation of unease, and the exquisite lighting and black and white tones are breathtakingly stark. There are moments in the film when there is so much going on in the scene, and the shot is so lengthy, that the situation itself becomes real and transcends the fiction of the film. This is a very rare phenomenon in film, and was absolutely spellbinding - especially the dance scene. The middle of the film gets heavy with bleak philosophical exchanges, which would be better illustrated than told - especially with Tarr's incredible gift for mis en scene and sound design. Iconographic sequences like the slow pan past the miserable crowds waiting for the rain to stop, or the reoccurring pack of wild dogs speak volumes more of Tarr's theme than the most eloquent words. The characters are like automatons shuffling about in a purgatory from which there is no escape. It is as though the entire world was a flea-bag apartment building, a tattered old bar, and a vast field of mud and debris which one must traverse between the two.

The film that launched director Béla Tarr into international attention, Kárhozat is the Hungarian's first major investigation of the nature of humanity.

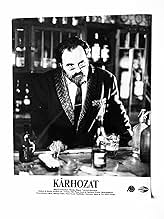

Trailing the exploits of alcoholic depressive Karrer, Kárhozat presents us with a view of a desolate and decrepit Hungarian town. He spends his days wandering from bar to bar, obsessing over a married lounge singer and part-time lover whom he longs to elope with. Passing off a job to collect a package to the husband, he buys himself three days alone with the object of his desires.

As is now his trademark, Tarr brings us the minimal number of shots: slow, winding, thoughtful and beautiful. His approach is simultaneously simple and complicated, showing us at the same time nothing and everything. The aesthetic of the film is astounding, beauty created wonderfully in the chaos and destruction of the landscape. The brooding intensity of the omnipresent coal trains dominates the work, an indicator of lost industry and decline. Miklós Székely leads the cast with the perfect stoic facade, his granite face holding back the weight of an emotional past and the crippling need for escape. The sinister and critical bartender gives us Karrer's true opinion of himself, one he would rather not face up to, whilst the sagacious old woman provides the film's sensibility and reason. The plot itself is not so important as the camera's journey and the character's silent ruminations, leading unavoidably to a wonderful climax and one which does exactly what it should: causes us to question our own lives and the oddity of humankind.

With beautiful, paced, unconventional direction, Tarr gives us an intimate portrait of ourselves and our world. Achieving an incredible amount with a minimalistic approach, the film is entrancing, mysterious, and inspiring. Telling us as much with his landscapes as with his characters, Tarr's Kárhozat is a testament to the brilliance of this creative juggernaut.

Trailing the exploits of alcoholic depressive Karrer, Kárhozat presents us with a view of a desolate and decrepit Hungarian town. He spends his days wandering from bar to bar, obsessing over a married lounge singer and part-time lover whom he longs to elope with. Passing off a job to collect a package to the husband, he buys himself three days alone with the object of his desires.

As is now his trademark, Tarr brings us the minimal number of shots: slow, winding, thoughtful and beautiful. His approach is simultaneously simple and complicated, showing us at the same time nothing and everything. The aesthetic of the film is astounding, beauty created wonderfully in the chaos and destruction of the landscape. The brooding intensity of the omnipresent coal trains dominates the work, an indicator of lost industry and decline. Miklós Székely leads the cast with the perfect stoic facade, his granite face holding back the weight of an emotional past and the crippling need for escape. The sinister and critical bartender gives us Karrer's true opinion of himself, one he would rather not face up to, whilst the sagacious old woman provides the film's sensibility and reason. The plot itself is not so important as the camera's journey and the character's silent ruminations, leading unavoidably to a wonderful climax and one which does exactly what it should: causes us to question our own lives and the oddity of humankind.

With beautiful, paced, unconventional direction, Tarr gives us an intimate portrait of ourselves and our world. Achieving an incredible amount with a minimalistic approach, the film is entrancing, mysterious, and inspiring. Telling us as much with his landscapes as with his characters, Tarr's Kárhozat is a testament to the brilliance of this creative juggernaut.

Você sabia?

- CuriosidadesWith "Kárhozat / Damnation", the first of his collaborations with novelist Laszlo Krasznahorkai, Bela Tarr adopts a formally rigorous style, featuring long takes and slow tracking shots of the bleak landscape that surrounds the characters.

- Erros de gravaçãoIn the Dance/Party scene, the band and the music are clearly out of sync.

- Citações

The Singer: I like the rain. I like to watch the water run down the window. It calms me down. I don't think about anything. I just watch the rain.

- ConexõesEdited into Gli ultimi giorni dell'umanità (2022)

Principais escolhas

Faça login para avaliar e ver a lista de recomendações personalizadas

- How long is Damnation?Fornecido pela Alexa

Detalhes

- Tempo de duração

- 2 h(120 min)

- Cor

- Mixagem de som

- Proporção

- 1.66 : 1

Contribua para esta página

Sugerir uma alteração ou adicionar conteúdo ausente