Um modesto trabalhador de escritório é preso e julgado, mas nunca é informado de suas acusações.Um modesto trabalhador de escritório é preso e julgado, mas nunca é informado de suas acusações.Um modesto trabalhador de escritório é preso e julgado, mas nunca é informado de suas acusações.

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Artistas

- Prêmios

- 2 vitórias e 2 indicações no total

- First Assistant Inspector

- (as William Kearns)

- Man in Leather

- (as Karl Studer)

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Elenco e equipe completos

- Produção, bilheteria e muito mais no IMDbPro

Avaliações em destaque

For the entirety of the long scene in K's bedroom, and throughout the major part of the film, Welles positions the camera slightly below waist height. This 'wrong' spatial relationship creates in the viewer a vague sense of unease, a visual disorientation which compounds K's emotional loss of bearings. Welles plays clever tricks with the proportions of the rooms, their lines being slightly out of kilter, and the ceilings very much in view. Typically, Welles is deliberately and flamboyantly breaking a cardinal rule of cinematography - 'keep the ceiling out of shot'. Interiors seem open and spacious if we can't see the ceiling, and Welles is after the converse effect: driving home the point that K inhabits an airless, joyless place and his surroundings are imbued with inchoate hostility.

German expressionism had gripped Welles' imagination back in the 1930's, and virtually all of his films show its abiding influence. The columns of the opera house represent social regimentation, and K offends against social conformity by awkwardly pushing his way out of the theatre, an irregular irritant polluting the symmetry of the seating. When K gets caught in the exodus of workers from the office, he is both literally and metaphorically swimming against the tide. His microscopic ineffectuality against the ponderous stateliness of the courtroom doors drives home the expressionist point - he is a puny Jonah, entering the cavernous bowels of The State.

"To be in chains is sometimes safer than being free," and it could be said that Welles' genius flourished best when shackled by a dearth of resources. Lacking the money for costumes during the shooting of "Othello", Welles turned adversity to artistic advantage, filming the murder scene in a turkish bath, not only obviating the need for clothing but also making a succinct point about Iago's motives being 'stripped bare'. "The Trial" affords another example of Welles' remarkable fecundity. Zitorelli's studio is built of cheap slats and lit from outside, creating a powerful cinematic image of The State's placeman clinging precariously to his wretched privileges - all filmed at practically no expense. The skewed, empty picture frames are silent comments on the distorted and barren perspective of Zitorelli, the human race's Benedict Arnold.

K is a Freudian picaro, journeying in despair through the intestines of a nightmare system of justice, an apparatus ironically designed to ensure that justice is stifled. The shades of Buchenwald are introduced by Welles. Defendants wait with meathooks above their heads and, in other parts of this unfathomable 'system', nameless naked unfortunates stand in quiet misery, their numbers hanging from their necks. Leni and The Wife are grotesque distortions of Dante's Beatrice, malformed guides with no sense of direction and no transcendent vision. Welles himself plays Hassler the advocate, the bully who has no thought of his client's welfare but seeks only to perpetuate the cruel gavotte of litigation. "The confusion's impenetrable," a point reinforced by shooting characters through interminable patterns of beams and girders, whose shifting geometry engulfs the insignificant humans.

In his 1985 biography of Welles, Charles Higham declared "The Trial" a failure, concluding that it was "muffled, dull, unexciting on every level". Perhaps more tellingly, he criticised Welles for adopting a grandiose approach, whereas Kafka's work cries out for spareness and understatement. Higham is excellent, but the film is not, in my humble opinion, a failure. It evokes with emotional power a dreamspace of despair, and in so doing renders a great service to Kafka's oeuvre.

I don't believe that Kafka ever published The Trial during his lifetime. In his will he left instructions that all his literary manuscripts should be destroyed after his death. In what was, perhaps, the final irony of Kafka's life, it was only the disobedience of the executor of the writer's estate that made the peculiarly paranoid world Kafka had created available to the public at all.

See this film and, afterwords, try to get a peaceful night's sleep.

Welles is one of the three primary inventors of cinema. And when he says this film is his best -- and autobiographical to boot -- one should sit up and take notice.

It is a remarkable experience, this film. Here are some elements I found interesting that are not yet noted here.

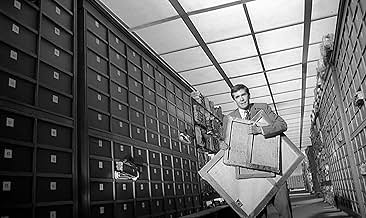

The impressive interiors are in a then abandoned train station. Today, that building houses the world's greatest collection of impressionist and postmodern art. One can walk around that museum and locate many of the locations used. It is an unhappy building now: it has many objects as important as this film or the book it is based on -- and their intent is as iconoclastic as Welles and Kafka, but it is run as a heavyhanded, relatively totalitarian institution. One gets much the same feeling of trapped artists now walking around it as one gets from this film.

Here's a puzzle for you: what black and white film was made in Europe by a master filmmaker; released in 1963; is a surreal depiction of an artist's angst; uses the device of many lovers or potential lovers in an imaginary array of sexual partners; arranged according to stereotype; is autobiographical and considered by the filmmaker his best. Both this and 8 1/2. Too many similarities for this to be accidental, including some stylistic touches (the painter). Both are films about film-making.

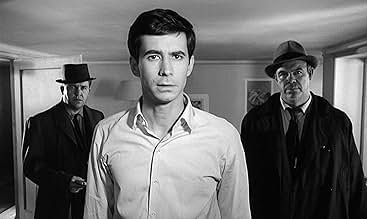

Welles uses actors in a then unusual way. It had long been the practice to take actors of ordinary skill and fit them to characters that more or less match their personality. But that practice simply took advantage of what the actor could do and was as much a matter of the actor exploiting the system as anything else. Welles here exploits Perkins, an actor who hasn't a clue about what is going on and so never finds the character. Clearly Welles wanted the effect of utter disorientation and knew Perkins could not consciously produce it.

Others have since used this technique (the Coens come to mind), sometimes with celebrities who will be really ticked when they emerge from their fogs.

A final interesting element: the framing. Welles is a master of mixing and conflating narrative methods. 'Kane' surely holds the record. Here, he is constrained by the pre-existing text: it is important that there be few narrative threads: Perkins' confusion and denial; the 'state's version; and the whole thing may be a dream or paranoid vision. Welles for instance cannot imply that the whole thing is one of the painter's paintings for instance, something he would have included in a flash if he could. So he extends his narrative layers offscreen by explicitly referencing it as a play he is doing, as a book (a 'dirty' book), and most creatively as an illustrated parable. He frames the film with drawings that are halfway between book illustrations and theatrical set designs. And he narrates them in a manner halfway between a drama and a reading. Very, very clever use of framing to increase the narrative layers by reference beyond what you see.

Ted's Evaluation: 3 of 4 -- Worth watching.

Você sabia?

- CuriosidadesIn May '62, while filming, Jeanne Moreau suffered a slight nervous breakdown due to the stifling atmosphere of the film.

- Erros de gravaçãoWhen Josef K. follows Hilda being carried out of the large trial room/hall by the law student, he hastily grabs and throws on his suit jacket. In the succeeding scenes, the jacket's buttons which are buttoned change.

- Citações

[first lines]

Narrator: Before the law, there stands a guard. A man comes from the country, begging admittance to the law. But the guard cannot admit him. May he hope to enter at a later time? That is possible, said the guard. The man tries to peer through the entrance. He'd been taught that the law was to be accessible to every man. "Do not attempt to enter without my permission", says the guard. I am very powerful. Yet I am the least of all the guards. From hall to hall, door after door, each guard is more powerful than the last. By the guard's permission, the man sits by the side of the door, and there he waits. For years, he waits. Everything he has, he gives away in the hope of bribing the guard, who never fails to say to him "I take what you give me only so that you will not feel that you left something undone." Keeping his watch during the long years, the man has come to know even the fleas on the guard's fur collar. Growing childish in old age, he begs the fleas to persuade the guard to change his mind and allow him to enter. His sight has dimmed, but in the darkness he perceives a radiance streaming immortally from the door of the law. And now, before he dies, all he's experienced condenses into one question, a question he's never asked. He beckons the guard. Says the guard, "You are insatiable! What is it now?" Says the man, "Every man strives to attain the law. How is it then that in all these years, no one else has ever come here, seeking admittance?" His hearing has failed, so the guard yells into his ear. "Nobody else but you could ever have obtained admittance. No one else could enter this door! This door was intended only for you! And now, I'm going to close it." This tale is told during the story called "The Trial". It's been said that the logic of this story is the logic of a dream... a nightmare.

- Cenas durante ou pós-créditosThe end cast credits are read over by Orson Welles without titles (though the actors are read in a different order from their listing on the screen).

- Versões alternativasThe short version cut the opening pin screen sequence and also deleted and rearranged a number of scenes.

- ConexõesFeatured in The Queen of Sheba Meets the Atom Man (1963)

- Trilhas sonorasAdagio D'Albinoni

Interprété par André Girard (as A. Girard) et Orchestre de l'Association des Concerts Colonne

Arranged by Jean Ledrut

Music by Tomaso Albinoni (T.Albinoni)

Publisher: S.l. : Philips, 1962.

Principais escolhas

Detalhes

- Data de lançamento

- Países de origem

- Central de atendimento oficial

- Idioma

- Também conhecido como

- The Trial

- Locações de filme

- 240 Grada Vukovara Street, Zagreb, Croácia(Joseph K. and old lady lugging a trunk)

- Empresas de produção

- Consulte mais créditos da empresa na IMDbPro

Bilheteria

- Orçamento

- US$ 1.300.000 (estimativa)

- Faturamento bruto nos EUA e Canadá

- US$ 93.533

- Fim de semana de estreia nos EUA e Canadá

- US$ 7.280

- 11 de dez. de 2022

- Faturamento bruto mundial

- US$ 94.243

- Tempo de duração1 hora 59 minutos

- Cor

- Proporção

- 1.66 : 1

Contribua para esta página