AVALIAÇÃO DA IMDb

7,6/10

11 mil

SUA AVALIAÇÃO

Um cafetão sem outros meios para se sustentar vê sua vida sair do controle quando sua prostituta é mandada para a prisão.Um cafetão sem outros meios para se sustentar vê sua vida sair do controle quando sua prostituta é mandada para a prisão.Um cafetão sem outros meios para se sustentar vê sua vida sair do controle quando sua prostituta é mandada para a prisão.

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Artistas

- Indicado para 1 prêmio BAFTA

- 3 vitórias e 4 indicações no total

Avaliações em destaque

The term 'accattone' is an old Italian phrase intended to brand a character with an aura of absolute repulsiveness. Thieves and low-lives would usually coin the term when referring to a character that is so despicable, so without moral or social decency, that even the criminals would look down upon them. In Pier Paolo Pasolini's incredibly assured debut, 'Accattone' is Vittorio (Franco Citti), a low-life pimp who when he is not sitting around squeezing money out of people with wagers and tricks, is abusing his lone prostitute who cannot work after breaking her leg in a motorcycle accident. It's a tale of a despicable scumbag, set during a dark period in Rome, where men viewed working as slave labour, and enjoyed themselves by beating prostitutes to within an inch of their life.

It's an incredibly bleak tale, told without sentiment and moral preaching. Pasolini's doesn't seem to want to dictate a larger social message, or make Accattone a sympathetic character who is the victim of political or social oppression, but to simply tell a tale, a real tale, of a group of low-lives who are the way they are because they want to be. After all, the true soul of neo-realism is to portray life the way actual people experience it, not to romanticise or sentimentalise it with the kind of scripts Hollywood are responsible for. Of course, many neo-realist directors would almost betray the genres roots the kind of way only auteurs can manage, and Pasolini would go on to make more surrealistic and interpretive movies, but this is true neo-realism without any kind of magical reward for the audience, or a moment of redemptive enlightenment for its protagonist. It's a story of grit, one that is thrilling and fascinating in equal measures, and with the stamp of a great director.

The film I felt it more akin to is Luis Bunuel's Los Olvidados (1950), a film of equal disregard for cinematic wonder, and one that is also punctured by an impressive dream sequence. Whilst Bunuel's sequence came around the middle section, and was a burst of absolute surrealistic beauty amongst social depravity, Accattone's comes during its climax; a strange, moody set-piece in which Accattone witnesses his own funeral, amongst other things. At first I felt like it was almost betraying what came before, but then I realised it was Pasolini's way to try and get into its characters head, and the outcome is as confusing and as futile as Accattone himself. Though I haven't seen much of Pasolini's work, this is the best I've seen, beating even the distressing brilliance of his final film Salo (1975). Though he would move away from neo-realism, Pasolini achieves more with his debut than some of the greats of the genre would manage to achieve.

www.the-wrath-of-blog.blogspot.com

It's an incredibly bleak tale, told without sentiment and moral preaching. Pasolini's doesn't seem to want to dictate a larger social message, or make Accattone a sympathetic character who is the victim of political or social oppression, but to simply tell a tale, a real tale, of a group of low-lives who are the way they are because they want to be. After all, the true soul of neo-realism is to portray life the way actual people experience it, not to romanticise or sentimentalise it with the kind of scripts Hollywood are responsible for. Of course, many neo-realist directors would almost betray the genres roots the kind of way only auteurs can manage, and Pasolini would go on to make more surrealistic and interpretive movies, but this is true neo-realism without any kind of magical reward for the audience, or a moment of redemptive enlightenment for its protagonist. It's a story of grit, one that is thrilling and fascinating in equal measures, and with the stamp of a great director.

The film I felt it more akin to is Luis Bunuel's Los Olvidados (1950), a film of equal disregard for cinematic wonder, and one that is also punctured by an impressive dream sequence. Whilst Bunuel's sequence came around the middle section, and was a burst of absolute surrealistic beauty amongst social depravity, Accattone's comes during its climax; a strange, moody set-piece in which Accattone witnesses his own funeral, amongst other things. At first I felt like it was almost betraying what came before, but then I realised it was Pasolini's way to try and get into its characters head, and the outcome is as confusing and as futile as Accattone himself. Though I haven't seen much of Pasolini's work, this is the best I've seen, beating even the distressing brilliance of his final film Salo (1975). Though he would move away from neo-realism, Pasolini achieves more with his debut than some of the greats of the genre would manage to achieve.

www.the-wrath-of-blog.blogspot.com

Accattone announces a director, Pier Paolo Pasolini, who is a haunting/haunted poet from his surroundings and realist, someone who wants to put his eye on the world without flinching on the details of how 'ordinary' (of the street) people speak and interact, how raw and uninhibited they can be, these being the guys on the streets who are vulgar and coarse at best and at worst are abusers of women. But at the same time what one comes away with is poetry in documentary form - it's another level of neo-realism, a little more like an urban story than a post-war treatise that still throbs with the importance of those in poverty. Anytime I hear the song Matthaus Passion I'll immediately contemplate those harsh images of Vittorio Accattone, being cast aside by his family for being a pimp, or that poor girl being beaten at night by that gang of men, which is something that elevates such hard scenes into art.

Vittorio Accattone is the main character- charming and attractive, and also a perpetual scoundrel who also is a total outcast. He has a wife and kid(s), but is estranged from them by choice - her choice most likely - and he finds himself in big trouble once his main prostitute, Maddalena, is sent to prison for a bad informing job. It's after this we see Accatone on his potential path to redemption when he meets a supremely sweet and average girl from out of town, Stella, who he may eye as a new girl on the street... or perhaps not, as his attachment to her grows more and stronger, in spite of what and who are around him every day and night in the dirty province.

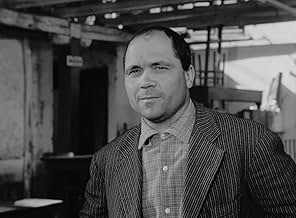

He's someone we want to root for in being a better person, or, perhaps even, better at what he does. He's a tragic anti-hero in a New-Wave sort of sense, cool looking and aspiring to be modern and cool (and maybe he is, up to a point), but also poor and uneducated, so much so that being on the fringe and being called "PIMP!" is what he's been reduced to by default. The performance from Franco Citti is one thing that keeps the viewer locked in: he's so good here because he looks plucked right off the street by Pasolini, as would turn to be his method with choosing most of his 'actors' on camera. There's a reality to his interactions with his friends (so called) or his business associates. Some of their dialog and tones of speech aren't refined or look trained. At one point when Citti's Vittorio breaks down in tears- a sudden turn from a previous scene showing more attitude- is authentic, even as another actor could have possibly played it "better".

It is what Pasolini wants, and he gets it, much in the same way he also gets a view of this side of Rome in a way that hasn't been seen before up until this time. His DP Tonino Delli Colli shoots simply often, and sometimes not so much - there's complexity, say, to a tracking shot in front of Accatone talking to a girl who is on a bicycle, or when we see the horrorshow of the men taking Maddalena at night in the middle of nowhere, the only lights starkly coming from the car. The effect is nothing short of a slow-burn. While a few of the actors do fall a bit too flat, and some scenes come close to lagging around (the editing might be the most significant flaw here), the raw emotion and fire in the subject matter keeps things fascinating. You want to see what happens with this young guy, and it's his tragedy that gets us absorbed, even as the Bach music abstracts the sorrow, and agonizing poetry of the streets, and it's this that makes it a classic.

Only downside I must mention - if you live in the US, or happen to watch it on a DVD or online from Walter Bearer films, the print is just not very good. It's the sort where the white subtitles drop in and out of view depending on who's standing where in a frame. It's not totally detrimental, but some scenes become hard to follow due to the poor quality of the subtitles with the print. This, if for no other reason, demands the film receive the Criteron treatment.

Vittorio Accattone is the main character- charming and attractive, and also a perpetual scoundrel who also is a total outcast. He has a wife and kid(s), but is estranged from them by choice - her choice most likely - and he finds himself in big trouble once his main prostitute, Maddalena, is sent to prison for a bad informing job. It's after this we see Accatone on his potential path to redemption when he meets a supremely sweet and average girl from out of town, Stella, who he may eye as a new girl on the street... or perhaps not, as his attachment to her grows more and stronger, in spite of what and who are around him every day and night in the dirty province.

He's someone we want to root for in being a better person, or, perhaps even, better at what he does. He's a tragic anti-hero in a New-Wave sort of sense, cool looking and aspiring to be modern and cool (and maybe he is, up to a point), but also poor and uneducated, so much so that being on the fringe and being called "PIMP!" is what he's been reduced to by default. The performance from Franco Citti is one thing that keeps the viewer locked in: he's so good here because he looks plucked right off the street by Pasolini, as would turn to be his method with choosing most of his 'actors' on camera. There's a reality to his interactions with his friends (so called) or his business associates. Some of their dialog and tones of speech aren't refined or look trained. At one point when Citti's Vittorio breaks down in tears- a sudden turn from a previous scene showing more attitude- is authentic, even as another actor could have possibly played it "better".

It is what Pasolini wants, and he gets it, much in the same way he also gets a view of this side of Rome in a way that hasn't been seen before up until this time. His DP Tonino Delli Colli shoots simply often, and sometimes not so much - there's complexity, say, to a tracking shot in front of Accatone talking to a girl who is on a bicycle, or when we see the horrorshow of the men taking Maddalena at night in the middle of nowhere, the only lights starkly coming from the car. The effect is nothing short of a slow-burn. While a few of the actors do fall a bit too flat, and some scenes come close to lagging around (the editing might be the most significant flaw here), the raw emotion and fire in the subject matter keeps things fascinating. You want to see what happens with this young guy, and it's his tragedy that gets us absorbed, even as the Bach music abstracts the sorrow, and agonizing poetry of the streets, and it's this that makes it a classic.

Only downside I must mention - if you live in the US, or happen to watch it on a DVD or online from Walter Bearer films, the print is just not very good. It's the sort where the white subtitles drop in and out of view depending on who's standing where in a frame. It's not totally detrimental, but some scenes become hard to follow due to the poor quality of the subtitles with the print. This, if for no other reason, demands the film receive the Criteron treatment.

In the poor periphery of Rome of the 60's, the despicable caftan Vittorio "Accattone" Cataldi (Franco Citti) is maintained by the hooker Maddalena (Silvana Corsini), spending the time with his useless idle friends. When the prostitute is arrested for perjury, the pimp "Accattone" has nobody to support him, but he seduces the naive worker Stella (Franca Pasut) and she becomes a whore. However, Accattone has a crush on Stella and decides to find a way to support her, with tragic consequences.

"Accattone" is the stunning debut of the great director Pier Paolo Pasolini. He returns to the theme of the misery of Italy in the postwar, explored in many Italian neo-realist movies such as Fellini's "Le Notti di Cabiria" (1957) and Visconti's "Rocco e i Suoi Fratelli" (1960), and magnificently shows the lifestyle of great part of the population in Italy, its lower class, with lack of perspective, starvation, prostitution and unemployment. Considering that this movie is also the debut or the beginning of the career of most actors and actresses, it is amazing how Pasolini was able to make such gem. My vote is nine.

Title (Brazil): "Accattoni Desajuste Social" ("Accattoni Social Maladjustment")

"Accattone" is the stunning debut of the great director Pier Paolo Pasolini. He returns to the theme of the misery of Italy in the postwar, explored in many Italian neo-realist movies such as Fellini's "Le Notti di Cabiria" (1957) and Visconti's "Rocco e i Suoi Fratelli" (1960), and magnificently shows the lifestyle of great part of the population in Italy, its lower class, with lack of perspective, starvation, prostitution and unemployment. Considering that this movie is also the debut or the beginning of the career of most actors and actresses, it is amazing how Pasolini was able to make such gem. My vote is nine.

Title (Brazil): "Accattoni Desajuste Social" ("Accattoni Social Maladjustment")

Accattone is a Neo-Realist examination of slovenly irresponsibility, tastelessness and self-pity - you know, the fun stuff. Its principal characters, a group of young upwardly-immobile Roman males, are almost uniformly repulsive, a lot of chest-baring half-savages whose idea of fun is luring a whore to a deserted spot and beating her to within an inch of her life. Its hero, Accattone, is played by one of the more unpleasant actors in the history of film, a fellow named Franco Citti, who manages to single-handedly set the entire nation of Italy back about two-hundred years. It is a film of almost relentless despair, depicting a Rome so desolate and squalid, so bereft of hope, that it seems almost medieval. In the hands of almost any director the movie would be unbearable - either unbearably sentimental or unbearably grim - but with Pasolini at the helm it is merely honest.

It isn't Pasolini's best film by a long way, but it may be the clearest example of what made the director so special - his ability to probe around the most revolting recesses of the human condition without seeming sensationalistic, exploitive or crass. It would be easy to go one of two directions with a character like Accattone, a lazy two-bit pimp with a son by a woman who wants nothing to do with him: the sentimental route or the grotesque. One could easily imagine De Sica, the soft-heart of Neo-Realism, turning Accattone into a sympathetic, misunderstood Everyman. And one could just as easily imagine Fellini, the most uptight director maybe in history, transforming the character into a universal symbol of societal decay. Pasolini, neither a sentimentalist nor a moralist, sees Accattone not as a sympathetic character nor as a symbol. The least judgmental director maybe ever, Pasolini conceives his characters entirely in terms of their outward behavior, and not in moral terms. He neither psycho-analyzes nor seeks to "understand" his characters. He simply presents them as they are, warts and all.

It was always the purpose of Neo-Realism to present life as it was lived, not life as it was imagined by screenwriters, directors and actors, and there are few more successful ventures in this regard than Accattone. The film's main triumph is in its atmosphere. The Roman days have never seemed so sun-bleached, so arid and oppressive; its nights never so mysterious, so full of inexpressible longing (not even in Henry James). The characters seem bound to this world in a palpable way, their faces (shot by expert cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli) mirroring the desolation, the hopelessness, the strangeness of their surroundings. The movie's physicality, as always with Pasolini, is striking. But pure physical vigor, pure atmosphere isn't enough. Where Pasolini comes up short is in assembling the parts of his film into something with real emotional breadth. His first feature shows him already on his way to being a master of the image, but also shows that he had a lot to learn about being a master of cinematic rhythm. The strange blend of primitivism and modernism is already there but the command is not. It's a film that works well in the moment but feels thin as a whole. It's a triumph of Neo-Realist technique but it only half-succeeds as a film.

Half-successful Pasolini is still better than the best most directors have to give. If you can portray a character as repulsive, as boorish and ego-maniacal as Accattone - a character with few if any redeeming features - for two hours without alienating your audience...well, chalk one up for the director who can do that. Especially one who manages the trick without resorting to sentimental contrivance or the kind of false significance people like Fellini always tried to drum up by filling their movies with obvious symbols, the sorts of things art-film zombies love because it gives them a chance to show their alleged smarts. Pasolini never flatters his audience but he never sneers at them either. He attempts to neither ingratiate himself with the public nor antagonize it in the manner of certain self-important avant-gardists. The best artists look for what interests them in a piece of material, not worrying whether their ideas, their approach, their style is accessible to the public at large, or critics, or scholars, or their grandmothers or anyone else. Accattone shows Pasolini on the road that would make him one of cinema's best directors - a road traveled by precisely one person, Pasolini himself.

It isn't Pasolini's best film by a long way, but it may be the clearest example of what made the director so special - his ability to probe around the most revolting recesses of the human condition without seeming sensationalistic, exploitive or crass. It would be easy to go one of two directions with a character like Accattone, a lazy two-bit pimp with a son by a woman who wants nothing to do with him: the sentimental route or the grotesque. One could easily imagine De Sica, the soft-heart of Neo-Realism, turning Accattone into a sympathetic, misunderstood Everyman. And one could just as easily imagine Fellini, the most uptight director maybe in history, transforming the character into a universal symbol of societal decay. Pasolini, neither a sentimentalist nor a moralist, sees Accattone not as a sympathetic character nor as a symbol. The least judgmental director maybe ever, Pasolini conceives his characters entirely in terms of their outward behavior, and not in moral terms. He neither psycho-analyzes nor seeks to "understand" his characters. He simply presents them as they are, warts and all.

It was always the purpose of Neo-Realism to present life as it was lived, not life as it was imagined by screenwriters, directors and actors, and there are few more successful ventures in this regard than Accattone. The film's main triumph is in its atmosphere. The Roman days have never seemed so sun-bleached, so arid and oppressive; its nights never so mysterious, so full of inexpressible longing (not even in Henry James). The characters seem bound to this world in a palpable way, their faces (shot by expert cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli) mirroring the desolation, the hopelessness, the strangeness of their surroundings. The movie's physicality, as always with Pasolini, is striking. But pure physical vigor, pure atmosphere isn't enough. Where Pasolini comes up short is in assembling the parts of his film into something with real emotional breadth. His first feature shows him already on his way to being a master of the image, but also shows that he had a lot to learn about being a master of cinematic rhythm. The strange blend of primitivism and modernism is already there but the command is not. It's a film that works well in the moment but feels thin as a whole. It's a triumph of Neo-Realist technique but it only half-succeeds as a film.

Half-successful Pasolini is still better than the best most directors have to give. If you can portray a character as repulsive, as boorish and ego-maniacal as Accattone - a character with few if any redeeming features - for two hours without alienating your audience...well, chalk one up for the director who can do that. Especially one who manages the trick without resorting to sentimental contrivance or the kind of false significance people like Fellini always tried to drum up by filling their movies with obvious symbols, the sorts of things art-film zombies love because it gives them a chance to show their alleged smarts. Pasolini never flatters his audience but he never sneers at them either. He attempts to neither ingratiate himself with the public nor antagonize it in the manner of certain self-important avant-gardists. The best artists look for what interests them in a piece of material, not worrying whether their ideas, their approach, their style is accessible to the public at large, or critics, or scholars, or their grandmothers or anyone else. Accattone shows Pasolini on the road that would make him one of cinema's best directors - a road traveled by precisely one person, Pasolini himself.

Accattone is a Roman pimp who lives off his girlfriend Maddalena's earnings. Pasolini's cheeky aim is to put forward this young man as a modern saint. To this end he lathers Bach's St Matthew's Passion (inspired by the Apostle's experience of the crucifixion of Christ) over scenes of Accattone's life. Indeed in one of Accattone's first scenes he's shown devouring a slice of tomato, displayed horizontally as if a cardinal's galero, whilst an sculpture of perhaps a guardian angel can be seen over his shoulder in the distance (an anti-clerical pro-Christ stance seems to be a consistent theme for Pasolini). Later, a prophecy regarding Accattone's descent is eerily similar to Christ's pronunciation of Peter's forthcoming triple renunciation.

The film reminded me of a DH Lawrence poem (elliptically titled Democracy):

"I love the sun in any man / when I see it between his brows / clear, and fearless, even if tiny // But when I see these grey successful men / so hideous and corpse-like, utterly sunless, / like gross successful slaves mechanically waddling / then I am more than radical, I want to work a guillotine

...

I feel that when people have gone utterly sunless / they shouldn't exist."

Whatever Accattone is, he's not sunless; when he tries out the world of work (legitimate work involving labour), he becomes Vittorio, his Christian name, and the light goes out. The film reminds me very much of Fassbinder's Gods of the Plague in that sense, young men with brio but no skills or education who, given the choice, between drudgery or crime, choose crime. Both films polemicise against urban post-industrial capitalist societies, which have become increasingly removed from the milieu in which humanity evolved and is "designed" to cope with. When Accattone compares the chore of lifting rolls of iron with the horrors of Buchenwald the film goes a little over the top.

Of course someone viewing Accattone and his friends through less of a haze of desire than the director might think that they were just a bunch of jerks. Undeniably though, Pasolini is a great poet, and there's evidence of things to come here, the film whilst looking largely Bertoluccian (he was the assistant director), has the occasional master shot, for example the rolling hills and valley in the dream sequence, par with Leonardo in quality of composition and symbolism; the countryside here representing an idealised rural precursor to Accattone's slum existence.

I also applaud Pasolini for taking his arguments beyond class, Accattone's group of spongers contains educated men as well as dunces, and they are equally disdainful of the ruling class as they are of proletarians.

The film reminded me of a DH Lawrence poem (elliptically titled Democracy):

"I love the sun in any man / when I see it between his brows / clear, and fearless, even if tiny // But when I see these grey successful men / so hideous and corpse-like, utterly sunless, / like gross successful slaves mechanically waddling / then I am more than radical, I want to work a guillotine

...

I feel that when people have gone utterly sunless / they shouldn't exist."

Whatever Accattone is, he's not sunless; when he tries out the world of work (legitimate work involving labour), he becomes Vittorio, his Christian name, and the light goes out. The film reminds me very much of Fassbinder's Gods of the Plague in that sense, young men with brio but no skills or education who, given the choice, between drudgery or crime, choose crime. Both films polemicise against urban post-industrial capitalist societies, which have become increasingly removed from the milieu in which humanity evolved and is "designed" to cope with. When Accattone compares the chore of lifting rolls of iron with the horrors of Buchenwald the film goes a little over the top.

Of course someone viewing Accattone and his friends through less of a haze of desire than the director might think that they were just a bunch of jerks. Undeniably though, Pasolini is a great poet, and there's evidence of things to come here, the film whilst looking largely Bertoluccian (he was the assistant director), has the occasional master shot, for example the rolling hills and valley in the dream sequence, par with Leonardo in quality of composition and symbolism; the countryside here representing an idealised rural precursor to Accattone's slum existence.

I also applaud Pasolini for taking his arguments beyond class, Accattone's group of spongers contains educated men as well as dunces, and they are equally disdainful of the ruling class as they are of proletarians.

Você sabia?

- CuriosidadesThis was Bernardo Bertolucci's first work in movies. He was an assistant director.

- Erros de gravaçãoThe shadow of the camera is clearly visible on Accattone's shirt when he walks away towards the camera after the fight with Ascenza's Brother.

- Citações

Vittorio "Accattone" Cataldi: Call me Accattone. There are lots of Vittorios but I'm the only Accattone.

- Versões alternativasThe VHS and DVD versions produced by Water Bearer Films are listed as running 116 minutes, suggesting that this print is four minutes shorter than the original release.

- Trilhas sonorasSt Matthew Passion

Composed by Johann Sebastian Bach

Principais escolhas

Faça login para avaliar e ver a lista de recomendações personalizadas

- How long is Accattone?Fornecido pela Alexa

Detalhes

Bilheteria

- Faturamento bruto mundial

- US$ 2.865

- Tempo de duração1 hora 57 minutos

- Cor

- Mixagem de som

- Proporção

- 1.37 : 1

Contribua para esta página

Sugerir uma alteração ou adicionar conteúdo ausente

Principal brecha

By what name was Accattone - Desajuste Social (1961) officially released in India in English?

Responda