IMDb रेटिंग

6.2/10

2.6 हज़ार

आपकी रेटिंग

अपनी भाषा में प्लॉट जोड़ेंTravelers in the 1870s Southwest discuss a recent murder trial in which all the principals told differing stories about the events.Travelers in the 1870s Southwest discuss a recent murder trial in which all the principals told differing stories about the events.Travelers in the 1870s Southwest discuss a recent murder trial in which all the principals told differing stories about the events.

फ़ीचर्ड समीक्षाएं

I'm glad I saw this film. It's probably of not much interest to someone who isn't a student of film...but if you're familiar with Kurosawa's "Rashomon" or the camera work of James Wong Howe, then it's worth a view.

Then again....maybe you don't need to be a film buff.

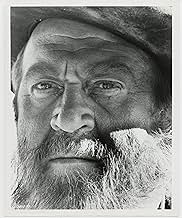

Capt. James T. Kirk as a preacher. Paul Newman with a bad mustache and equally suspicious accent. Edward G. Robinson chewing the scenery. Howard Da Silva wearing either a tumbleweed or a small dog.

When a few minutes in, and it became clear to me that this was going to be a fairly "faithful" remake of the original...I settled in for the long haul, dreading what was to come as Hollywood took a masterpiece and "westernized" it. It wasn't as bad as I expected. I agree with an earlier comment that the final "re-telling" is pretty funny.

I teach "Rashomon" in my History of Film course. I realize that many western students just can't fully appreciate much of the Japanese culture packed into Kurosawa's work. I'd love to figure a way to show "Rashomon" and "The Outrage" back-to-back. The better students might appreciate the artistry of Kurosawa a bit more; the lunk-heads might finally figure out what was going on. At least a couple of idiots each term seem to think the wife and the medium in "Rashomon" are the same woman. In "The Outrage" it's kinda hard to mistake Claire Bloom for an elderly Native American man.

Then again....maybe you don't need to be a film buff.

Capt. James T. Kirk as a preacher. Paul Newman with a bad mustache and equally suspicious accent. Edward G. Robinson chewing the scenery. Howard Da Silva wearing either a tumbleweed or a small dog.

When a few minutes in, and it became clear to me that this was going to be a fairly "faithful" remake of the original...I settled in for the long haul, dreading what was to come as Hollywood took a masterpiece and "westernized" it. It wasn't as bad as I expected. I agree with an earlier comment that the final "re-telling" is pretty funny.

I teach "Rashomon" in my History of Film course. I realize that many western students just can't fully appreciate much of the Japanese culture packed into Kurosawa's work. I'd love to figure a way to show "Rashomon" and "The Outrage" back-to-back. The better students might appreciate the artistry of Kurosawa a bit more; the lunk-heads might finally figure out what was going on. At least a couple of idiots each term seem to think the wife and the medium in "Rashomon" are the same woman. In "The Outrage" it's kinda hard to mistake Claire Bloom for an elderly Native American man.

If you're going to do a movie with multiple flashbacks told from different points of view, the ground covered in those flashbacks better be damned interesting. Such is not the case here. Each witness' version of the events in question becomes progressively more pedestrian until the final one is played for laughs. This is the movie's point, of course, that people would rather believe well-spun myths which confirm their own preconceived notions about human nature than a banal truth that won't conform. All fine and good, but it's a danged self-destructive way to tell a story. Especially when James Wong Howe's apocalyptic visuals (those rain-drenched scenes at the isolated train station are almost Blade Runner-ish in their darkness and despair) are gearing you up from the first moment for some grimly powerful examination of evil.

The sad fact is that Laurence Harvey and Claire Bloom, as the victimized husband and wife at the heart of the film, do not come across as terribly noteworthy or distinctive. You keep waiting for some explosive revelation that might account for the idealistic Parson (played by William Shatner - young and fresh-faced but overly-mannered even then) to be so shattered by the incident that he loses his faith, but no luck. Edward G. Robinson is excellent as the old con artist with no illusions about mankind, while a close to unrecognizable Paul Newman does an entertaining Anthony Quinn impression as the dastardly bandito.

The train station segments are sensational, film-making at its best, but the endless flashbacks are flat and tedious as hell, making this film a uniquely disappointing experience.

The sad fact is that Laurence Harvey and Claire Bloom, as the victimized husband and wife at the heart of the film, do not come across as terribly noteworthy or distinctive. You keep waiting for some explosive revelation that might account for the idealistic Parson (played by William Shatner - young and fresh-faced but overly-mannered even then) to be so shattered by the incident that he loses his faith, but no luck. Edward G. Robinson is excellent as the old con artist with no illusions about mankind, while a close to unrecognizable Paul Newman does an entertaining Anthony Quinn impression as the dastardly bandito.

The train station segments are sensational, film-making at its best, but the endless flashbacks are flat and tedious as hell, making this film a uniquely disappointing experience.

Sometimes, I'm amazed at the low level of commentary on these films. This one is no exception. The reviewer opening these comments comments on a "Western" as if this were a Roy Rogers or Gene Autry oater. While I'm aware that we all have the right to express our views, I would like to see a little more insight on those selecting which reviews will be presented. This film is a remake and reset of the Kurusawa classic and is a classic in its own right. Fine, fine performances are given by Newman, Harvey, Bloom, Shatner(in his pre-Kirk days), Robinson, Salmi, Da Silva and Fix in this casting of a Japanese film play-- which is a composite of two stories, BTW-- by Akira Kurusawa. It's not perfect. The role of the medium, the old Indian shaman portrayed by veteran character actor, Paul Fix, doesn't have the cultural impact of the original. There is confusion around the rape and fight scene, but these are small things. The film is marvelous and the black and white setting captures much of the shading and light contrasts of the original Rashomon. The story in both films, which Kurusawa wove out of two earlier stories, is full of archetypes but lacking much of the impending chaos of the original. The first tale of the old gate at kyoto tells of a ronin confronting an old woman and taking the blanket from an abandoned child in the time of civil war and political upheaval; the other tale, in the woods, tells of the various versions of rape, murder, honor and shame, told by each of the participants. Kurusawa blended them into an excellent film story. While the cultural background of the original sets it apart from this American version, there is much that does make it work. The genteel Southern couple, the Mexican bandido, the pragmatic sheriff, the country preacher, the snake-oil salesman and the miner/prospector, fit the Samurai, bandit, medium, etc., of the original very well. So, face it. It ain't John Wayne. But it's good cinema at it best.

Paul Newman plays a Mexican bandit so convincingly in "The Outrage" (Martin Ritt, 1964) that it's extremely difficult to recognize Newman at all. Far from being a star vehicle, the Paul Newman "persona" isn't recognizable here in the least. I must admit that for quite a while, I kept wondering when Newman was going to finally arrive on the screen, before it dawned upon me that Newman was playing the bandit. I wouldn't deem his amoral, animalistic, lusty performance brilliant because it constitutes a rather stereotypical caricature of a Mexican bandit. Nevertheless, Newman disguises himself so dramatically, to the point where "Paul Newman" is almost invisible, that his performance becomes noteworthy just the same.

Overall, Martin Ritt's Western remake of Akira Kurosawa's landmark and legendary "Rashomon" (Kurosawa, 1950) is worth viewing despite some obvious flaws. Ritt doesn't add anything new to Kurosawa's famous study in subjective truth and point-of-view prejudice, and at times, "The Outrage," which was also taken from a then-recent Broadway play, appears a bit flat and copied. Indeed, it occasionally seems as if Ritt grows bored with the story that he's copying from Kurosawa and Broadway and that he's yearning for comedy and satire in his otherwise straight remake. However, those alternative tones are never fully developed and as a result the film fails to make a dynamic impact. That same year, over in Spain, Italian director Sergio Leone remade Kurosawa's Samurai classic "Yojimbo" (1961) as a Western, but he did so with epochal results, largely because he brought a whole new visual style (a patient, rhythmic balance of stunning panorama and extreme close-ups) and directorial slant (a fluid study in operatic nihilism and surrealism) to Kurosawa's story. In other words, Leone remade a Kurosawa film and in doing so, he transformed it into something vastly different. In "The Outrage," Ritt fails to pull off the same trick.

That said, there are some aspects that recommend "The Outrage" to the viewer, and Newman's chameleon performance is just one of them. All of Ritt's remarkable directorial trademarks are on display here: his ambiguity; his objectivity; his refusal to condescend to the audience; the moral shadiness that he evokes; his rejection of black-or-white moral simplicity; his implicit and unstrained social commentary (in this case revolving around the holy trinity of race, class, and gender, not to mention regionalism); his spare, ominously striking visuality; his meditative pacing. Perhaps most noteworthy is James Wong Howe's haunting black-and-white cinematography, which reflects an ominous glow and projects an apocalyptic sensibility rather than Western grandeur. Instead of macrocosmic vistas, Howe's compositions capture a sense of claustrophobia, moral confusion, and subjective truth thanks to their low-angle and eye-level confinement. Through his camera-work, the Western landscape becomes not a romantic frontier or an open-air arena, but instead an entangling thicket where honor and honesty descend in a squalid ravine. Most remarkable are the crepuscular, stormy, forbidding shots of a forsaken railway station during a desert thunderstorm. It is here that three observers (one of which is deliciously played by the always memorable Edward G. Robinson) discuss the different versions of truth while refraining from spelling out the implications for the audience. Ritt, as usual, forces the viewer to think for him or herself. And what Ritt reveals are the human motivationspride, vanity, contempt, guilt, shame, distrust, lust, cowardice, avarice, survivalthat color the notion of truth and ultimately render it subjective. Unfortunately, as a straight remake, "The Outrage"'s presentation of these themes is a little too flat and perfunctory to leave a fresh impact. Still, the film is compelling and curious, standing as an artistic, sobering Western and the most obscure oater that Paul Newman ever starred in. And of course, Newman virtually obscures himself by becoming another.

Overall, Martin Ritt's Western remake of Akira Kurosawa's landmark and legendary "Rashomon" (Kurosawa, 1950) is worth viewing despite some obvious flaws. Ritt doesn't add anything new to Kurosawa's famous study in subjective truth and point-of-view prejudice, and at times, "The Outrage," which was also taken from a then-recent Broadway play, appears a bit flat and copied. Indeed, it occasionally seems as if Ritt grows bored with the story that he's copying from Kurosawa and Broadway and that he's yearning for comedy and satire in his otherwise straight remake. However, those alternative tones are never fully developed and as a result the film fails to make a dynamic impact. That same year, over in Spain, Italian director Sergio Leone remade Kurosawa's Samurai classic "Yojimbo" (1961) as a Western, but he did so with epochal results, largely because he brought a whole new visual style (a patient, rhythmic balance of stunning panorama and extreme close-ups) and directorial slant (a fluid study in operatic nihilism and surrealism) to Kurosawa's story. In other words, Leone remade a Kurosawa film and in doing so, he transformed it into something vastly different. In "The Outrage," Ritt fails to pull off the same trick.

That said, there are some aspects that recommend "The Outrage" to the viewer, and Newman's chameleon performance is just one of them. All of Ritt's remarkable directorial trademarks are on display here: his ambiguity; his objectivity; his refusal to condescend to the audience; the moral shadiness that he evokes; his rejection of black-or-white moral simplicity; his implicit and unstrained social commentary (in this case revolving around the holy trinity of race, class, and gender, not to mention regionalism); his spare, ominously striking visuality; his meditative pacing. Perhaps most noteworthy is James Wong Howe's haunting black-and-white cinematography, which reflects an ominous glow and projects an apocalyptic sensibility rather than Western grandeur. Instead of macrocosmic vistas, Howe's compositions capture a sense of claustrophobia, moral confusion, and subjective truth thanks to their low-angle and eye-level confinement. Through his camera-work, the Western landscape becomes not a romantic frontier or an open-air arena, but instead an entangling thicket where honor and honesty descend in a squalid ravine. Most remarkable are the crepuscular, stormy, forbidding shots of a forsaken railway station during a desert thunderstorm. It is here that three observers (one of which is deliciously played by the always memorable Edward G. Robinson) discuss the different versions of truth while refraining from spelling out the implications for the audience. Ritt, as usual, forces the viewer to think for him or herself. And what Ritt reveals are the human motivationspride, vanity, contempt, guilt, shame, distrust, lust, cowardice, avarice, survivalthat color the notion of truth and ultimately render it subjective. Unfortunately, as a straight remake, "The Outrage"'s presentation of these themes is a little too flat and perfunctory to leave a fresh impact. Still, the film is compelling and curious, standing as an artistic, sobering Western and the most obscure oater that Paul Newman ever starred in. And of course, Newman virtually obscures himself by becoming another.

I am familiar with Kurosawa's "Rashomon", which is original work interestingly remade in Hollywood by Martin Ritt. Those who have seen both works will be able to note the obvious virtues of the original. Yet, I saw this film with no prior knowledge of the fact that this was a remake of Rashomon.

What struck me within minutes of opening of the film was the unusual camerawork of James Hong Howe, that takes pleasure in close-ups and tilted shots that are reminescent of European cinema of the sixties. It is so far removed in style from Hollywood.

Reams of paper have used to write about Akutagawa's story immortalized by Kurosawa. So I have nothing to add on the brilliant story that obviously attracted Ritt and the playwrights Kanin.

What is unusual is Ritt's treatment. His choice of actors are interesting--Claire Bloom is a fine choice as she has a range of emotions to display with credibility; Laurence Harvey's role is limited even though he occupies a long screentime gagged and bound but he has to show scorn for a brief period the gag is removed without speaking--and when he speaks his face is not visible; Edward G Robinson is a perfect choice for a snake oil salesman and so on...

Ritt's use of the soundtrack is again non-Hollywood in style. He uses music and uses silence with great effect while characters talk to underline the emotions. Kurosawa did it to the extreme limits that makes it odd for the non-Japanese viewer.

Ritt is an interesting director. I have always admired his choice of subjects to film. I prefer his black and white films to his color projects because of the subjects that he chose to film--"Edge of the City" being one of my favorite Ritt works. The second reason I admire him is for his choice of actors, especially for the major female roles. He has derived great performances as he did here with Bloom.

This film will never be talked about because it is a remake of a classic. However, in my view it stands out as unlike John Sturges' "Magnificent Seven," which was also a remake of another Kurosawa work in Hollywood, this film adopted a different style closer to Europe and Japan. It is essentially a fine work of depicting a play on film somewhat like nuggets of celluloid gold found among the works of the American Film Theatre series.

What struck me within minutes of opening of the film was the unusual camerawork of James Hong Howe, that takes pleasure in close-ups and tilted shots that are reminescent of European cinema of the sixties. It is so far removed in style from Hollywood.

Reams of paper have used to write about Akutagawa's story immortalized by Kurosawa. So I have nothing to add on the brilliant story that obviously attracted Ritt and the playwrights Kanin.

What is unusual is Ritt's treatment. His choice of actors are interesting--Claire Bloom is a fine choice as she has a range of emotions to display with credibility; Laurence Harvey's role is limited even though he occupies a long screentime gagged and bound but he has to show scorn for a brief period the gag is removed without speaking--and when he speaks his face is not visible; Edward G Robinson is a perfect choice for a snake oil salesman and so on...

Ritt's use of the soundtrack is again non-Hollywood in style. He uses music and uses silence with great effect while characters talk to underline the emotions. Kurosawa did it to the extreme limits that makes it odd for the non-Japanese viewer.

Ritt is an interesting director. I have always admired his choice of subjects to film. I prefer his black and white films to his color projects because of the subjects that he chose to film--"Edge of the City" being one of my favorite Ritt works. The second reason I admire him is for his choice of actors, especially for the major female roles. He has derived great performances as he did here with Bloom.

This film will never be talked about because it is a remake of a classic. However, in my view it stands out as unlike John Sturges' "Magnificent Seven," which was also a remake of another Kurosawa work in Hollywood, this film adopted a different style closer to Europe and Japan. It is essentially a fine work of depicting a play on film somewhat like nuggets of celluloid gold found among the works of the American Film Theatre series.

क्या आपको पता है

- ट्रिवियाPaul Newman was concerned about his accent, so he spent two weeks in Mexico with dialect coach Walon Green.

- गूफ़When the Wife (Bloom) is fighting Juan (Newman), she falls and hits the camera rig, causing the picture to shake a little.

- क्रेज़ी क्रेडिटExcept for the title and company name, the beginning of the movie has no opening credits.

- कनेक्शनFeatured in MGM 40th Anniversary (1964)

टॉप पसंद

रेटिंग देने के लिए साइन-इन करें और वैयक्तिकृत सुझावों के लिए वॉचलिस्ट करें

- How long is The Outrage?Alexa द्वारा संचालित

विवरण

- रिलीज़ की तारीख़

- कंट्री ऑफ़ ओरिजिन

- भाषाएं

- इस रूप में भी जाना जाता है

- Judgement in the Sun

- फ़िल्माने की जगहें

- उत्पादन कंपनी

- IMDbPro पर और कंपनी क्रेडिट देखें

बॉक्स ऑफ़िस

- बजट

- $30,00,000(अनुमानित)

- चलने की अवधि1 घंटा 36 मिनट

- रंग

- पक्ष अनुपात

- 2.39 : 1

इस पेज में योगदान दें

किसी बदलाव का सुझाव दें या अनुपलब्ध कॉन्टेंट जोड़ें