IMDb रेटिंग

7.9/10

64 हज़ार

आपकी रेटिंग

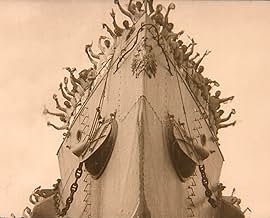

1905 की रूसी क्रांति के दौरान, युद्धपोत पोटेमकिन का चालक दल पोत के अधिकारियों के क्रूर, अत्याचारी शासन के खिलाफ विद्रोह करता हैं. ओडेसा में सड़क प्रदर्शन के परिणामस्वरूप पुलिस नरसंहार होता ह... सभी पढ़ें1905 की रूसी क्रांति के दौरान, युद्धपोत पोटेमकिन का चालक दल पोत के अधिकारियों के क्रूर, अत्याचारी शासन के खिलाफ विद्रोह करता हैं. ओडेसा में सड़क प्रदर्शन के परिणामस्वरूप पुलिस नरसंहार होता है.1905 की रूसी क्रांति के दौरान, युद्धपोत पोटेमकिन का चालक दल पोत के अधिकारियों के क्रूर, अत्याचारी शासन के खिलाफ विद्रोह करता हैं. ओडेसा में सड़क प्रदर्शन के परिणामस्वरूप पुलिस नरसंहार होता है.

- पुरस्कार

- कुल 1 जीत

Ivan Bobrov

- Young Sailor Flogged While Sleeping

- (as I. Bobrov)

Nina Poltavtseva

- Woman With Pince-nez

- (as N. Poltavtseva)

Iona Biy-Brodskiy

- Student

- (as Brodsky)

Sergei Eisenstein

- Odessa Citizen

- (as Sergei M. Eisenstein)

Andrey Fayt

- Recruit

- (as A. Fait)

सारांश

Reviewers say 'Battleship Potemkin' is acclaimed for its pioneering montage and editing, significantly impacting cinema. The 1905 Russian Revolution portrayal, especially the Odessa Steps scene, is lauded for its potent visuals and emotional resonance. Many praise its technical innovations and contribution to filmmaking. However, some criticize its political propaganda and shallow character development. Nonetheless, 'Battleship Potemkin' is widely recognized as a cinematic masterpiece and a vital historical film.

फ़ीचर्ड समीक्षाएं

Originally supposed to be just a part of a huge epic The Year 1905 depicting the Revolution of 1905, Potemkin is the story of the mutiny of the crew of the Potemkin in Odessa harbor. The film opens with the crew protesting maggoty meat and the captain ordering the execution of the dissidents. An uprising takes place during which the revolutionary leader is killed. This crewman is taken to the shore to lie in state. When the townspeople gather on a huge flight of steps overlooking the harbor, czarist troops appear and march down the steps breaking up the crowd. A naval squadron is sent to retake the Potemkin but at the moment when the ships come into range, their crews allow the mutineers to pass through. Eisenstein's non-historically accurate ending is open-ended thus indicating that this was the seed of the later Bolshevik revolution that would bloom in Russia. The film is broken into five parts: Men and Maggots, Drama on the Quarterdeck, An Appeal from the Dead, The Odessa Steps, and Meeting the Squadron.

Eisenstein was a revolutionary artist, but at the genius level. Not wanting to make a historical drama, Eisenstein used visual texture to give the film a newsreel-look so that the viewer feels he is eavesdropping on a thrilling and politically revolutionary story. This technique is used by Pontecorvo's The Battle of Algiers.

Unlike Pontecorvo, Eisenstein relied on typage, or the casting of non-professionals who had striking physical appearances. The extraordinary faces of the cast are what one remembers from Potemkin. This technique is later used by Frank Capra in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and Meet John Doe. But in Potemkin, no one individual is cast as a hero or heroine. The story is told through a series of scenes that are combined in a special effect known as montage--the editing and selection of short segments to produce a desired effect on the viewer. D.W. Griffith also used the montage, but no one mastered it so well as Eisenstein.

The artistic filming of the crew sleeping in their hammocks is complemented by the graceful swinging of tables suspended from chains in the galley. In contrast the confrontation between the crew and their officers is charged with electricity and the clenched fists of the masses demonstrate their rage with injustice.

Eisenstein introduced the technique of showing an action and repeating it again but from a slightly different angle to demonstrate intensity. The breaking of a plate bearing the words "Give Us This Day Our Daily Bread" signifies the beginning of the end. This technique is used in Last Year at Marienbad. Also, when the ship's surgeon is tossed over the side, his pince-nez dangles from the rigging. It was these glasses that the officer used to inspect and pass the maggot-infested meat. This sequence ties the punishment to the corruption of the czarist-era.

The most noted sequence in the film, and perhaps in all of film history, is The Odessa Steps. The broad expanse of the steps are filled with hundreds of extras. Rapid and dramatic violence is always suggested and not explicit yet the visual images of the deaths of a few will last in the minds of the viewer forever.

The angular shots of marching boots and legs descending the steps are cleverly accentuated with long menacing shadows from a sun at the top of the steps. The pace of the sequence is deliberately varied between the marching soldiers and a few civilians who summon up courage to beg them to stop. A close up of a woman's face frozen in horror after being struck by a soldier's sword is the direct antecedent of the bank teller in Bonnie in Clyde and gives a lasting impression of the horror of the czarist regime.

The death of a young mother leads to a baby carriage careening down the steps in a sequence that has been copied by Hitchcock in Foreign Correspondent, by Terry Gilliam in Brazil, and Brian DePalma in The Untouchables. This sequence is shown repeatedly from various angles thus drawing out what probably was only a five second event.

Potemkin is a film that immortalizes the revolutionary spirit, celebrates it for those already committed, and propagandizes it for the unconverted. It seethes of fire and roars with the senseless injustices of the decadent czarist regime. Its greatest impact has been on film students who have borrowed and only slightly improved on techniques invented in Russia several generations ago.

Eisenstein was a revolutionary artist, but at the genius level. Not wanting to make a historical drama, Eisenstein used visual texture to give the film a newsreel-look so that the viewer feels he is eavesdropping on a thrilling and politically revolutionary story. This technique is used by Pontecorvo's The Battle of Algiers.

Unlike Pontecorvo, Eisenstein relied on typage, or the casting of non-professionals who had striking physical appearances. The extraordinary faces of the cast are what one remembers from Potemkin. This technique is later used by Frank Capra in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and Meet John Doe. But in Potemkin, no one individual is cast as a hero or heroine. The story is told through a series of scenes that are combined in a special effect known as montage--the editing and selection of short segments to produce a desired effect on the viewer. D.W. Griffith also used the montage, but no one mastered it so well as Eisenstein.

The artistic filming of the crew sleeping in their hammocks is complemented by the graceful swinging of tables suspended from chains in the galley. In contrast the confrontation between the crew and their officers is charged with electricity and the clenched fists of the masses demonstrate their rage with injustice.

Eisenstein introduced the technique of showing an action and repeating it again but from a slightly different angle to demonstrate intensity. The breaking of a plate bearing the words "Give Us This Day Our Daily Bread" signifies the beginning of the end. This technique is used in Last Year at Marienbad. Also, when the ship's surgeon is tossed over the side, his pince-nez dangles from the rigging. It was these glasses that the officer used to inspect and pass the maggot-infested meat. This sequence ties the punishment to the corruption of the czarist-era.

The most noted sequence in the film, and perhaps in all of film history, is The Odessa Steps. The broad expanse of the steps are filled with hundreds of extras. Rapid and dramatic violence is always suggested and not explicit yet the visual images of the deaths of a few will last in the minds of the viewer forever.

The angular shots of marching boots and legs descending the steps are cleverly accentuated with long menacing shadows from a sun at the top of the steps. The pace of the sequence is deliberately varied between the marching soldiers and a few civilians who summon up courage to beg them to stop. A close up of a woman's face frozen in horror after being struck by a soldier's sword is the direct antecedent of the bank teller in Bonnie in Clyde and gives a lasting impression of the horror of the czarist regime.

The death of a young mother leads to a baby carriage careening down the steps in a sequence that has been copied by Hitchcock in Foreign Correspondent, by Terry Gilliam in Brazil, and Brian DePalma in The Untouchables. This sequence is shown repeatedly from various angles thus drawing out what probably was only a five second event.

Potemkin is a film that immortalizes the revolutionary spirit, celebrates it for those already committed, and propagandizes it for the unconverted. It seethes of fire and roars with the senseless injustices of the decadent czarist regime. Its greatest impact has been on film students who have borrowed and only slightly improved on techniques invented in Russia several generations ago.

An epic of the Russian revolution, Battleship Potemkin, perhaps not so correctly historically, addresses the Russian revolution of 1905. With memorable scenes, especially the flag and the staircase scenes, Russian cinema is perhaps not so shy about showing violence. Which ends up enhancing and giving a more shocking experience when watching the film. A great movie considering the time it was released.

If you're a film student, or were one, or are thinking of becoming one, the name Battleship Potemkin has or will have a resonance. Sergei Eistenstein, like other silent-film pioneers like Griffith (although Eisenstein's innovations are not as commonplace as Griffith's) and Murnau, has had such an impact on the history of cinema it's of course taken for granted. The reason I bring up the film student part is because at some point, whether you'd like it or not, your film professor 9 times out of 10 will show the "Odessa Stairs" sequence of this film. It's hard to say if it's even the 'best' part of the film's several sequences dealing with the (at the time current) times of the Russian revolution. But it does leave the most impact, and it can be seen in many films showcasing suspense, or just plain montage (The Untouchables' climax comes to mind).

Montage, which was not just Eistenstein's knack but also his life's blood early in his career, is often misused in the present cinema, or if not misused then in an improper context for the story. Sometimes montage is used now as just another device to get from point A to point B. Montage was something else for Eisenstein; he was trying to communicate in the most direct way that he could the urgency, the passion(s), and the ultimate tragedies that were in the Russian people at the time and place. Even if one doesn't see all of Eisenstein's narrative or traditional 'story' ideas to have much grounding (Kubrick has said this), one can't deny the power of seeing the ships arriving at the harbor, the people on the stairs, and the soldiers coming at them every which way with guns. Some may find it hard to believe this was done in the 20's; it has that power like the Passion of Joan of Arc to over-pass its time and remain in importance if only in terms of technique and emotion.

Of course, one could go on for books (which have been written hundreds of times over, not the least of which by Eisenstein himself). On the film in and of itself, Battleship Potemkin is really more like a dramatized newsreel than a specific story in a movie. The first segment is also one of the great sequences in film, as a mutiny is plotted against the Captain and other head-ups of a certain Ship. This is detailed almost in a manipulative way, but somehow extremely effective; montage is used here as well, but in spurts of energy that capture the eye. Other times Eisenstein is more content to just let the images speak for themselves, as the soldiers grow weary without food and water. He isn't one of those directors who will try to get all sides to the story; he is, of course, very much early 20th century Russian, but he is nothing else but honest with how he sees his themes and style, and that is what wins over in the end.

Some may want to check it outside of film-school, as the 'Stairs' sequence is like one of those landmarks of severe tragedy on film, displaying the ugly side of revolution. Eisenstein may not be one of the more 'accessible' silent-film directors, but if montage, detail in the frame, non-actors, and Bolshevik themes are your cup of tea, it's truly one of the must sees of a lifetime.

Montage, which was not just Eistenstein's knack but also his life's blood early in his career, is often misused in the present cinema, or if not misused then in an improper context for the story. Sometimes montage is used now as just another device to get from point A to point B. Montage was something else for Eisenstein; he was trying to communicate in the most direct way that he could the urgency, the passion(s), and the ultimate tragedies that were in the Russian people at the time and place. Even if one doesn't see all of Eisenstein's narrative or traditional 'story' ideas to have much grounding (Kubrick has said this), one can't deny the power of seeing the ships arriving at the harbor, the people on the stairs, and the soldiers coming at them every which way with guns. Some may find it hard to believe this was done in the 20's; it has that power like the Passion of Joan of Arc to over-pass its time and remain in importance if only in terms of technique and emotion.

Of course, one could go on for books (which have been written hundreds of times over, not the least of which by Eisenstein himself). On the film in and of itself, Battleship Potemkin is really more like a dramatized newsreel than a specific story in a movie. The first segment is also one of the great sequences in film, as a mutiny is plotted against the Captain and other head-ups of a certain Ship. This is detailed almost in a manipulative way, but somehow extremely effective; montage is used here as well, but in spurts of energy that capture the eye. Other times Eisenstein is more content to just let the images speak for themselves, as the soldiers grow weary without food and water. He isn't one of those directors who will try to get all sides to the story; he is, of course, very much early 20th century Russian, but he is nothing else but honest with how he sees his themes and style, and that is what wins over in the end.

Some may want to check it outside of film-school, as the 'Stairs' sequence is like one of those landmarks of severe tragedy on film, displaying the ugly side of revolution. Eisenstein may not be one of the more 'accessible' silent-film directors, but if montage, detail in the frame, non-actors, and Bolshevik themes are your cup of tea, it's truly one of the must sees of a lifetime.

Sergei Eisenstein's silent masterpiece is a very influential and possibly the most famous landmark film ever made. Many, many memorable scenes, including one of the best and most powerful scenes in film history, the massacre on the Odessa steps. No film in our time has captured such power and amazement from one sequence. Along from being a landmark in film history, it also has a strong message on brotherhood and power hungry leaders. This one has stood the test of time and will for ever more.

With workers striking in Russia, the crew of the battleship Potemkin feel a certain kinship for the plight of their brothers. When they are served rotting, maggot infested meat some of the crew object, only to find themselves singled out and placed in front of a firing squad. With the marines seconds away from firing the deadly shots, ordinary seaman Grigory Vakulinchuk steps into the breach and intervenes to save the men by appealing to the firing squad to ignore their orders. When the officers take their revenge and kill Vakulinchuk, all are bonded together in the struggle; a bond that reaches to the city of Odessa where the rebellion grows, leading to a bloody and historic series of events.

It is hard to imagine that anybody who has seen quite a few films in the past few decades would be unaware of this film, but it is perhaps understandable that fewer have had the opportunity to actually sit down and watch. I had never seen this film before but had seen countless references to it in other films and therefore considering it an important film to at least see once. The story is based on real events and this only serves to make it more interesting but even without this context it is still an engaging story. The story doesn't have much in the way of characters but it still brings out the brutality and injustice of events and it is in this that it hooked me surprisingly violent (implied more than modern gore) it demonising the actions and shows innocents falling at all sides in key scenes. The version I saw apparently had the original score (I'm not being snobby modern rescores could be better for all I know) and I felt it worked very well to match and improve the film's mood; dramatic, gentle or exciting, it all works very well.

The feel of the film was a surprise to me because it stood up very well viewed with my modern eyes. At one or two points the model work was very clearly model work but mostly the film is technically impressive. The masses of extras, use of ships and cities and just the way it captures such well organised chaos are all very impressive and would be even done today. What is more impressive with time though is how the film has a very strong and very clean style to it it is not as gritty and flat as many silent films of the period that I have seen; instead it is very crisp and feels very, very professional. Of course watching it in 2004 gives me the benefit of hindsight where I can look back over many films that have referenced the images or directors who have mentioned the film in interviews; but even without this 20:20 vision it is still possible to see how well done the film is and to note how memorable much of it is the steps and the firing squad scenes are two very impressive moments that are very memorable. The only real thing that might bug modern audiences is the acting; it isn't bad but silent acting is very different from acting with sound. Here the actors all over act and rely on their bodies to do much of their delivery word cards just don't do the emotional job so they have to make extra effort to deliver this.

Overall this is a classic film that has influenced many modern directors. The story is engaging and well worth hearing; the directing is crisp and professional, producing many scenes that linger in the memory; the music works to deliver the emotional edge that modern audiences would normally rely on acting and dialogue to deliver and the whole film is over all too quickly! An essential piece of cinema for those that claim to love the media but also a cracking good film in its own right.

It is hard to imagine that anybody who has seen quite a few films in the past few decades would be unaware of this film, but it is perhaps understandable that fewer have had the opportunity to actually sit down and watch. I had never seen this film before but had seen countless references to it in other films and therefore considering it an important film to at least see once. The story is based on real events and this only serves to make it more interesting but even without this context it is still an engaging story. The story doesn't have much in the way of characters but it still brings out the brutality and injustice of events and it is in this that it hooked me surprisingly violent (implied more than modern gore) it demonising the actions and shows innocents falling at all sides in key scenes. The version I saw apparently had the original score (I'm not being snobby modern rescores could be better for all I know) and I felt it worked very well to match and improve the film's mood; dramatic, gentle or exciting, it all works very well.

The feel of the film was a surprise to me because it stood up very well viewed with my modern eyes. At one or two points the model work was very clearly model work but mostly the film is technically impressive. The masses of extras, use of ships and cities and just the way it captures such well organised chaos are all very impressive and would be even done today. What is more impressive with time though is how the film has a very strong and very clean style to it it is not as gritty and flat as many silent films of the period that I have seen; instead it is very crisp and feels very, very professional. Of course watching it in 2004 gives me the benefit of hindsight where I can look back over many films that have referenced the images or directors who have mentioned the film in interviews; but even without this 20:20 vision it is still possible to see how well done the film is and to note how memorable much of it is the steps and the firing squad scenes are two very impressive moments that are very memorable. The only real thing that might bug modern audiences is the acting; it isn't bad but silent acting is very different from acting with sound. Here the actors all over act and rely on their bodies to do much of their delivery word cards just don't do the emotional job so they have to make extra effort to deliver this.

Overall this is a classic film that has influenced many modern directors. The story is engaging and well worth hearing; the directing is crisp and professional, producing many scenes that linger in the memory; the music works to deliver the emotional edge that modern audiences would normally rely on acting and dialogue to deliver and the whole film is over all too quickly! An essential piece of cinema for those that claim to love the media but also a cracking good film in its own right.

क्या आपको पता है

- ट्रिवियाThe film censorship boards of several countries felt this movie would spread communism. France imposed a ban after a brief run in 1925; it lifted it in 1953 after the death of Russian leader Joseph Stalin. The UK banned it until 1954.

- गूफ़In the Imperial squadron near the end of the film, there are close-ups of triple gun turrets of Gangut-class dreadnought. It possibly was made this way to show the power of Imperial fleet, but battleships of 1905 were much smaller pre-dreadnoughts, with twin turrets only, just like "Potemkin". "Ganguts" entered service in 1914.

- इसके अलावा अन्य वर्जनSergei Eisenstein's premiere version opened with an unattributed quote from Leon Trotsky's "1905": The spirit of mutiny swept the land. A tremendous, mysterious process was taking place in countless hearts: the individual personality became dissolved in the mass, and the mass itself became dissolved in the revolutionary impetus. This quote was removed by Soviet censors in 1934, and replaced by a quotation from V.I. Lenin's "Revolutionary Days": Revolution is war. Of all the wars known in history, it is the only lawful, rightful, just and truly great war...In Russia this war has been declared and won. The original text was restored in 2004.

- कनेक्शनEdited into Seeds of Freedom (1943)

टॉप पसंद

रेटिंग देने के लिए साइन-इन करें और वैयक्तिकृत सुझावों के लिए वॉचलिस्ट करें

- How long is Battleship Potemkin?Alexa द्वारा संचालित

विवरण

- रिलीज़ की तारीख़

- कंट्री ऑफ़ ओरिजिन

- भाषाएं

- इस रूप में भी जाना जाता है

- Battleship Potemkin

- फ़िल्माने की जगहें

- Sevastopol, Crimea, युक्रेन(battleship scenes)

- उत्पादन कंपनी

- IMDbPro पर और कंपनी क्रेडिट देखें

बॉक्स ऑफ़िस

- US और कनाडा में सकल

- $51,198

- US और कनाडा में पहले सप्ताह में कुल कमाई

- $5,641

- 16 जन॰ 2011

- दुनिया भर में सकल

- $62,723

- चलने की अवधि1 घंटा 15 मिनट

- रंग

- ध्वनि मिश्रण

- पक्ष अनुपात

- 1.33 : 1

इस पेज में योगदान दें

किसी बदलाव का सुझाव दें या अनुपलब्ध कॉन्टेंट जोड़ें