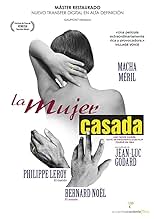

Une femme mariée

Titre original : Une femme mariée: Suite de fragments d'un film tourné en 1964

NOTE IMDb

7,1/10

4,6 k

MA NOTE

Une femme superficielle a du mal à choisir entre son mari violent et son amant vaniteux.Une femme superficielle a du mal à choisir entre son mari violent et son amant vaniteux.Une femme superficielle a du mal à choisir entre son mari violent et son amant vaniteux.

- Réalisation

- Scénario

- Casting principal

- Récompenses

- 2 nominations au total

Christophe Bourseiller

- Nicolas

- (as Chris Tophe)

Margareth Clémenti

- Girl in Swimming Pool

- (as Margaret Le-Van)

Jean-Luc Godard

- The Narrator

- (non crédité)

Avis à la une

We see a hand, then another hand, in the frame of the opening shot of Jean-Luc Godard's Une femme mariee. It's from here that we see a succession of images, all of the body but never anything explicit- a leg, a belly-button, hands, a back, a nude front but covered breasts. Godard is inquiring about the form of a body in and of itself while also trying to find new ways of photographing it. In these shots, which also happen again in this sort of physical poetry a couple of other times in the film, illustrate something both absorbing and elusive about the film in general.

It's about form and 'lifestyle, of the married life and the affair, of a bad husband and a tricky squeeze on the side... but then we also have scenes that puncture through the infidelity drama: there's a scene where Robert, the lover, and Charlotte, the main femme of the movie, are sitting in a movie theater at an airport, discreetly, and one wonders what they're about to watch (just before this an image of Hitchcock appears as if Charlotte sees it in the lobby), and it turns out to be some kind of holocaust documentary ala Night & Fog. They leave right away. Too much of a shock, or too much reality? How does the outside world affect these people?

We get a lot of scenes of characters just talking to one another, asking questions, sometimes in documentary form. Whether it's really Godard off camera asking the questions and turning it into a docu-narrative of some sort (the old Bazinian logic taken to an extreme that an actor in front of a camera is still in a documentary of the actor acting on camera perhaps), or the characters themselves is kept a little unclear. But this doesn't distract from the dialog and monologues being generally, genuinely intriguing and moving even. There's one scene in particular that I shall not forget easily, no pun intended, when Pierre, the husband, espouses about memory and how "impossible" it is for him to forget, and how rotten it can be for someone who has dealt with real horror (he recalls a story, as his character is a pilot, of talking to Roberto Rossellini about a concentration camp victim and memory and that it made him laugh - again, a very harsh contrast of Dachau and Auschwitz mentioned for interpretation).

This and a few other times when characters just go off on something has a lasting impact. Une femme Mariee is filled with the sort of cinematic rhythm that would immediately say to someone unfamiliar with foreign/art-house film, let alone Godard, "oh, that's an 'arty' movie". It certainly is: everything from its themes of alienated characters to its lyrical and original cinematography to the repetition of the Beethoven music (later used in Prenom Carmen) to image itself becomes an issue like when Charlotte obsesses over ladies wearing bras in a magazine, it's all from an artist who expresses his concerns in a my-way-or-the- highway attitude to the audience. And you want to go along with him, if curious enough, to see where he'll take his trio of characters in the Parisian settings. Sometimes there's even weird, dark humor, like when Charlotte finds a random record of some woman in agony and it's the sound of a woman just laughing - something that Charlotte and Pierre listen to in silence until Charlotte wants to put on another record and she becomes like a little kid trying to put it on without Pierre getting in her way.

What looks disjointed and without a plot is deceptive when looking at it in pieces. But somehow Godard's film works as a whole piece, and it's part of the point to find this character Charlotte not easy to figure out. The men in her life barely know themselves. And by the end, when it should be about the melodrama of a baby on the way, Godard side- steps this (already dealing with it comically in A Woman is a Woman), by making it about something else on the surface and underneath full of tension. Notice how demanding Charlotte is of answers from Robert about what it means to be an actor. He answers well and stands his ground, but it becomes noticeable that it's not about getting answers on acting or real love but about this woman's tortured self-made life. It's not emotionally gripping, but it gets one to think and it's this that makes Godard's film special in his cannon of great 1960's works.

It's about form and 'lifestyle, of the married life and the affair, of a bad husband and a tricky squeeze on the side... but then we also have scenes that puncture through the infidelity drama: there's a scene where Robert, the lover, and Charlotte, the main femme of the movie, are sitting in a movie theater at an airport, discreetly, and one wonders what they're about to watch (just before this an image of Hitchcock appears as if Charlotte sees it in the lobby), and it turns out to be some kind of holocaust documentary ala Night & Fog. They leave right away. Too much of a shock, or too much reality? How does the outside world affect these people?

We get a lot of scenes of characters just talking to one another, asking questions, sometimes in documentary form. Whether it's really Godard off camera asking the questions and turning it into a docu-narrative of some sort (the old Bazinian logic taken to an extreme that an actor in front of a camera is still in a documentary of the actor acting on camera perhaps), or the characters themselves is kept a little unclear. But this doesn't distract from the dialog and monologues being generally, genuinely intriguing and moving even. There's one scene in particular that I shall not forget easily, no pun intended, when Pierre, the husband, espouses about memory and how "impossible" it is for him to forget, and how rotten it can be for someone who has dealt with real horror (he recalls a story, as his character is a pilot, of talking to Roberto Rossellini about a concentration camp victim and memory and that it made him laugh - again, a very harsh contrast of Dachau and Auschwitz mentioned for interpretation).

This and a few other times when characters just go off on something has a lasting impact. Une femme Mariee is filled with the sort of cinematic rhythm that would immediately say to someone unfamiliar with foreign/art-house film, let alone Godard, "oh, that's an 'arty' movie". It certainly is: everything from its themes of alienated characters to its lyrical and original cinematography to the repetition of the Beethoven music (later used in Prenom Carmen) to image itself becomes an issue like when Charlotte obsesses over ladies wearing bras in a magazine, it's all from an artist who expresses his concerns in a my-way-or-the- highway attitude to the audience. And you want to go along with him, if curious enough, to see where he'll take his trio of characters in the Parisian settings. Sometimes there's even weird, dark humor, like when Charlotte finds a random record of some woman in agony and it's the sound of a woman just laughing - something that Charlotte and Pierre listen to in silence until Charlotte wants to put on another record and she becomes like a little kid trying to put it on without Pierre getting in her way.

What looks disjointed and without a plot is deceptive when looking at it in pieces. But somehow Godard's film works as a whole piece, and it's part of the point to find this character Charlotte not easy to figure out. The men in her life barely know themselves. And by the end, when it should be about the melodrama of a baby on the way, Godard side- steps this (already dealing with it comically in A Woman is a Woman), by making it about something else on the surface and underneath full of tension. Notice how demanding Charlotte is of answers from Robert about what it means to be an actor. He answers well and stands his ground, but it becomes noticeable that it's not about getting answers on acting or real love but about this woman's tortured self-made life. It's not emotionally gripping, but it gets one to think and it's this that makes Godard's film special in his cannon of great 1960's works.

Jean-Luc Godard's eighth feature film, UNE FEMME MARIÉE (A Married Woman, 1964) is a tale of adultery. As it opens, we meet Charlotte (Macha Meril) at a tryst with her lover Robert (Bernard Noël). Though Robert tries to convince her to divorce her husband, the pilot Pierre (Philippe Leroy), Charlotte's loyalties remain divided.

Godard labeled UNE FEMME MARIÉE not a "film" but rather "a collection of fragments from a film shot in 1964". However, this is much less avant-garde disjointed than one might expect. Godard chooses a fragment-based means of storytelling for the moments between Charlotte and her lover, presenting a sequence of brief dialogues between the lovers in rapid succession. Each of these self-encapsulated moments serves as another brick in the wall of what we know about the relationship. Such compressed storytelling manages to distill otherwise ineffable interpersonal dramas and feelings. The framing in the scenes between Charlotte and her lover is remarkable: close-up shots of their faces or limbs against featureless backgrounds. Generally the face of the person speaking is not shown and we hear only the words.

But while there had already been myriad such tales of love triangles through the ages, this film offers something fresh by combining it with a critique of 1960s consumer society. The characters pepper their conversation with commercial jingles, parrot whole advertising texts, or recite factoids. In shots of home life, the latest fancy name-brand cleaning products and electronics are placed prominently in the frame. Charlotte and her maid read women's magazines and see whether they live up to the standards of beauty that the media prescribes. The Auschwitz trials were going on at the same time as shooting, and Godard chose to work references to this into the characters' conversations. In this way, he underscores how consumer society emphasizes thinking about the present, buying whatever is called must-have now, and thus discourages self-reflection and critically gazing on the past. The film's message remains perennially fresh, and I think many viewers will enjoy UNE FEMME MARIEE.

Godard would take up the "housewife and consumerism" theme again three years later in 2 OU 3 CHOSES QUE JE SAIS D'ELLE, where this time the housewife prostitutes herself during the day to buy all the nice things that her husband can't. As a critique of consumerism, that later film is more successful inasmuch as it was shot in colour, and thus shows how commercial brands were using brash designs to draw the eye of shoppers. ("If you can't afford LSD," Godard says in a voice-over there, "buy a colour television.") However, UNE FEMME MARIEE is not just a rough sketch for the later film, and I'd even call it a better film, inasmuch as it tells a coherent story while the elements of the later one don't entirely come together for me.

Godard labeled UNE FEMME MARIÉE not a "film" but rather "a collection of fragments from a film shot in 1964". However, this is much less avant-garde disjointed than one might expect. Godard chooses a fragment-based means of storytelling for the moments between Charlotte and her lover, presenting a sequence of brief dialogues between the lovers in rapid succession. Each of these self-encapsulated moments serves as another brick in the wall of what we know about the relationship. Such compressed storytelling manages to distill otherwise ineffable interpersonal dramas and feelings. The framing in the scenes between Charlotte and her lover is remarkable: close-up shots of their faces or limbs against featureless backgrounds. Generally the face of the person speaking is not shown and we hear only the words.

But while there had already been myriad such tales of love triangles through the ages, this film offers something fresh by combining it with a critique of 1960s consumer society. The characters pepper their conversation with commercial jingles, parrot whole advertising texts, or recite factoids. In shots of home life, the latest fancy name-brand cleaning products and electronics are placed prominently in the frame. Charlotte and her maid read women's magazines and see whether they live up to the standards of beauty that the media prescribes. The Auschwitz trials were going on at the same time as shooting, and Godard chose to work references to this into the characters' conversations. In this way, he underscores how consumer society emphasizes thinking about the present, buying whatever is called must-have now, and thus discourages self-reflection and critically gazing on the past. The film's message remains perennially fresh, and I think many viewers will enjoy UNE FEMME MARIEE.

Godard would take up the "housewife and consumerism" theme again three years later in 2 OU 3 CHOSES QUE JE SAIS D'ELLE, where this time the housewife prostitutes herself during the day to buy all the nice things that her husband can't. As a critique of consumerism, that later film is more successful inasmuch as it was shot in colour, and thus shows how commercial brands were using brash designs to draw the eye of shoppers. ("If you can't afford LSD," Godard says in a voice-over there, "buy a colour television.") However, UNE FEMME MARIEE is not just a rough sketch for the later film, and I'd even call it a better film, inasmuch as it tells a coherent story while the elements of the later one don't entirely come together for me.

He did it in 1961, in 1962, in 1963, and in 1964 Godard made another movie about a woman questioning the meaning of love, life, and acting. This movie, like the others, is a fun treat for Godard fans and fans of inventive camera and editing techniques, though it doesn't have as much heart as "Contempt", "Une femme est une femme", or even "Vivre sa vie".

"Une femme mariee" depicts the affair of a bored housewife, but director Godard strives to convey the feeling that we are reading about her in a women's magazine. To achieve this the scenes with the actors abruptly cuts to fashion photos, make- up ads, and text. It's a stylish movie with a brisk pace, but, just like a magazine story, it doesn't take long for it to leave the mind or heart either. Yes, Godard's creativity may soar higher here than ever before. His playfulness leaps through the surprising angles and reveals, his panning of words in magazines, x-ray photography, and whispered narration, etc, yet the story seems tacked on. We float from idea to idea as they enter and leave the director's head, which is fun for a one-time viewing, probably the way that glancing at his sketchbook may feel, but the lack of motivation, of purpose, inevitably keeps this effort from standing in the same grouping as the previously mentioned works, the ones that we watch more frequently, the ones that give us cinematic nourishment, the more organic, more well-rounded, fully realized pieces.

"Une femme mariee" depicts the affair of a bored housewife, but director Godard strives to convey the feeling that we are reading about her in a women's magazine. To achieve this the scenes with the actors abruptly cuts to fashion photos, make- up ads, and text. It's a stylish movie with a brisk pace, but, just like a magazine story, it doesn't take long for it to leave the mind or heart either. Yes, Godard's creativity may soar higher here than ever before. His playfulness leaps through the surprising angles and reveals, his panning of words in magazines, x-ray photography, and whispered narration, etc, yet the story seems tacked on. We float from idea to idea as they enter and leave the director's head, which is fun for a one-time viewing, probably the way that glancing at his sketchbook may feel, but the lack of motivation, of purpose, inevitably keeps this effort from standing in the same grouping as the previously mentioned works, the ones that we watch more frequently, the ones that give us cinematic nourishment, the more organic, more well-rounded, fully realized pieces.

This time there's one female lead choosing between two men, something pretty rare in a medium usually fueled by male fantasies. Charlotte is a young middle-class married woman having an affair with an actor. She has promised her lover she'll divorce her husband, but an unplanned pregnancy makes her question that decision. The film follows her as she attempts to decide between them.

Like other Godard films that followed it (Masculin/Feminin, 2 or 3 Things, Made in USA) one of the primary themes here is the extent to which a modern individual's life is manipulated by commercial culture, and how it influences the choices we make. Perhaps because he had yet to fully mature as a filmmaker, this theme is much less subtle here than in those later films. Charlotte is barraged with nonsensical beauty ads and Cosmo-type articles about achieving the "perfect breast size," and in one famous shot is literally dwarfed by a billboard of "the perfect woman" in a bra. The height of social control is reached in the form of an absurd device her lover gives her that hooks around her waist like a belt and sounds an alarm every time her posture slackens. The effect of this visual over-stimulation on her is pernicious. Like the magazine ads we're shown, her thoughts (heard in voice-over) are fragmented and incoherent, indecisive and ultimately meaningless.

The other recurring Godardian theme appearing here is the commodification of the female body. To her bourgeois husband, who represents the patriarchal tradition and middle-class status quo, she's more an object to be protected (like the records he brings back from Germany) and exploited (he rapes her when she won't make love) than a human being to be understood. Ironically, his unwillingness to forgive a past infidelity and his possessive jealousy only compels her more to see freedom in a lover. But unlike her husband, who treats her like a commercial object, her lover treats her as a sex object ("Is it still love when it's from behind?" she wonders early in the film) and seems interested only in her body. Her scenes with him are composed of tightly-framed shots of his hand stroking her naked body, shots resembling the photographs selling stockings and bras in her magazines. Her lover literally sees her as a whole person only once, when she goes up on the roof naked. Accordingly, he gets angry, out of possessiveness. Godard's dim view of the condition of modern woman sees her as unable to break free of her past (her husband) due to the self-sufficiency and humanity she's denied in the present. As she ages, a woman's role goes from sex object to status-based commodity, and society teaches her that to think otherwise is wrong. This is a concept still ahead of its time today, when violent, over-sexualized junk like the Tomb Raider movies are sold as female empowerment.

As with most of Godard's films, there are always several things going on at once, and this capsule review barely scratches the surface. In the context of his career, the film is best understood as an early version of 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her, which he made three years later and is unquestionably better. By that film, Godard had learned to synthesize his social, emotional, and political themes into one seamless whole, discarding the artificial narrative conventions that serve him no purpose. This one, while no classic, is essential viewing for anyone interested in Godard's progression from brilliant filmmaker to serious artist.

Like other Godard films that followed it (Masculin/Feminin, 2 or 3 Things, Made in USA) one of the primary themes here is the extent to which a modern individual's life is manipulated by commercial culture, and how it influences the choices we make. Perhaps because he had yet to fully mature as a filmmaker, this theme is much less subtle here than in those later films. Charlotte is barraged with nonsensical beauty ads and Cosmo-type articles about achieving the "perfect breast size," and in one famous shot is literally dwarfed by a billboard of "the perfect woman" in a bra. The height of social control is reached in the form of an absurd device her lover gives her that hooks around her waist like a belt and sounds an alarm every time her posture slackens. The effect of this visual over-stimulation on her is pernicious. Like the magazine ads we're shown, her thoughts (heard in voice-over) are fragmented and incoherent, indecisive and ultimately meaningless.

The other recurring Godardian theme appearing here is the commodification of the female body. To her bourgeois husband, who represents the patriarchal tradition and middle-class status quo, she's more an object to be protected (like the records he brings back from Germany) and exploited (he rapes her when she won't make love) than a human being to be understood. Ironically, his unwillingness to forgive a past infidelity and his possessive jealousy only compels her more to see freedom in a lover. But unlike her husband, who treats her like a commercial object, her lover treats her as a sex object ("Is it still love when it's from behind?" she wonders early in the film) and seems interested only in her body. Her scenes with him are composed of tightly-framed shots of his hand stroking her naked body, shots resembling the photographs selling stockings and bras in her magazines. Her lover literally sees her as a whole person only once, when she goes up on the roof naked. Accordingly, he gets angry, out of possessiveness. Godard's dim view of the condition of modern woman sees her as unable to break free of her past (her husband) due to the self-sufficiency and humanity she's denied in the present. As she ages, a woman's role goes from sex object to status-based commodity, and society teaches her that to think otherwise is wrong. This is a concept still ahead of its time today, when violent, over-sexualized junk like the Tomb Raider movies are sold as female empowerment.

As with most of Godard's films, there are always several things going on at once, and this capsule review barely scratches the surface. In the context of his career, the film is best understood as an early version of 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her, which he made three years later and is unquestionably better. By that film, Godard had learned to synthesize his social, emotional, and political themes into one seamless whole, discarding the artificial narrative conventions that serve him no purpose. This one, while no classic, is essential viewing for anyone interested in Godard's progression from brilliant filmmaker to serious artist.

One of Godard's least seen films of the sixties,yet one of his most interesting and mature works.At first viewing it seems to be a typically Gallic story of adultery as the married woman of the title,Charlotte (Macha Méril)is torn between her airline pilot husband and her lover,an actor.But in contrast to how Truffaut,for example,treats adultery in the contemporaneous "La Peau Douce",Godard uses it as a pretext to explore the consumer culture of the sixties.He investigates the role which the media plays in forming Charlotte's tastes and opinions,focusing on the endless stream of advertisements,record sleeves,films and magazines to which she is exposed every day and which informs her views on every subject from politics to fashion. Her frequently naked body is seen in close-up,fragmented,com modified like all the other fetishistic images seen throughout the film.

As usual with Godard there is a plethora of references to filmic and literary figures who have influenced his work.There are a series of cinéma vérité type interviews with the husband,their son and filmmaker Roger Leenhardt which break up the narrative flow in an acknowledgement to Brecht,who would be a key figure in Godard's development in the next decade,whilst Charlotte indulges in several soliloquies reminiscent of Molly Bloom in "Ulysses",one of his favourite books.Formed by this melding together of disparate elements and techniques,"Une femme marieé" brilliantly expresses what it must have felt for a young woman to be alive in the summer of 1964.

As usual with Godard there is a plethora of references to filmic and literary figures who have influenced his work.There are a series of cinéma vérité type interviews with the husband,their son and filmmaker Roger Leenhardt which break up the narrative flow in an acknowledgement to Brecht,who would be a key figure in Godard's development in the next decade,whilst Charlotte indulges in several soliloquies reminiscent of Molly Bloom in "Ulysses",one of his favourite books.Formed by this melding together of disparate elements and techniques,"Une femme marieé" brilliantly expresses what it must have felt for a young woman to be alive in the summer of 1964.

Le saviez-vous

- AnecdotesRoughly 30 minutes into the film, in the scene where Pierre, Charlotte and Roger Leenhardt are sitting down in the living room, a small, cockroach looking-like insect crawls on the floor between Pierre's legs.

- ConnexionsFeatured in Godard, l'amour, la poésie (2007)

- Bandes originalesQuand le Film est Triste

(Sad Movies Make Me Cry)

Written by John D. Loudermilk

French lyrics by Georges Aber and Lucien Morisse

Performed by Sylvie Vartan

Meilleurs choix

Connectez-vous pour évaluer et suivre la liste de favoris afin de recevoir des recommandations personnalisées

- How long is A Married Woman?Alimenté par Alexa

Détails

- Date de sortie

- Pays d’origine

- Langue

- Aussi connu sous le nom de

- Une femme mariée: fragments d'un film tourné en 1964 en noir et blanc

- Lieux de tournage

- Sociétés de production

- Voir plus de crédits d'entreprise sur IMDbPro

Box-office

- Budget

- 120 000 $US (estimé)

- Durée1 heure 35 minutes

- Couleur

- Mixage

- Rapport de forme

- 1.37 : 1

Contribuer à cette page

Suggérer une modification ou ajouter du contenu manquant

Lacune principale

By what name was Une femme mariée (1964) officially released in India in English?

Répondre