IMDb-BEWERTUNG

6,2/10

7009

IHRE BEWERTUNG

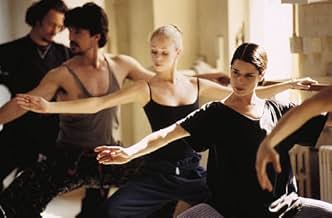

Füge eine Handlung in deiner Sprache hinzuA young ballet dancer is poised to become the principal performer in a group of ballet dancers.A young ballet dancer is poised to become the principal performer in a group of ballet dancers.A young ballet dancer is poised to become the principal performer in a group of ballet dancers.

- Auszeichnungen

- 2 Nominierungen insgesamt

Barbara E. Robertson

- Harriet

- (as Barbara Robertson)

Davis C. Robertson

- Alec - Joffrey Dancer

- (as Davis Robertson)

Empfohlene Bewertungen

The Company is far below the level of Robert Altman's best efforts. In contrast with Gosford Park's endlessly fascinating chatter weaving an intricate web of intrigues and secrets, there's much stretching and dancing, but very little delving into the backgrounds or relationships of the principals. There's hardly what you could call a plot. There are only a few strong characters. All you really get to hold things together somehow or provide some sense of continuity is a series of things that go wrong:

(1) Among the many dance `numbers,' the one that stands out is the first, an outdoor performance featuring the Hollywood actress Neve Campbell (Scream 1,2, and 3, Wild Things), a trained dancer and the force behind the making of the whole film. A thunderstorm comes to buffet the audience and the dancers. The dancers bravely go on and the dance -- so we're told, anyway -- is a triumph. The entire sequence is dominated by a sense of impending disaster. A slippery stage could have meant serious injury. One also wonders about damage to valuable string instruments being played in the open to accompany the dance. All this is extremely distracting and excruciating to watch. Altman does succeed though in giving us a sense of what performances are like from the company's point of view -- struggles with physical problems; successful efforts (at best) to avert disaster.

(2) An injury forces a new lead dancer to give up a role. This happens twice. We realize that dancers constantly face injury, or, as often, are dangerously in denial that they have one.

(3) Another sort of injury prevents a dancer from performing the whole of a `number.' This happens to Neve Campbell at the end of the movie. It's just an arm injury, so not career-threatening, but enough to require a quick replacement by a stand-in.

(4) A young man is replaced, but only for the latter part of a dance he's in -- because his energy seems to flag at that point in the performance. This nonetheless results in a terribly bruised ego for the young man and his union rep promises to lodge a formal protest. We get a sense of the constant threats to the ego in such an arbitrarily run system, along with the surprising news that union redress may be available in such cases.

(5) One of the guys in the company takes a new girlfriend. This time again it's Neve Campbell who's the `injured' one, and at a post-performance celebration she delivers an `I was the last to know' speech to the bad boy. I saw nods of agreement from dancerly-looking audience members during this moment.

(6) The aging female lead dancer - she's 43 - repeatedly protests about too-challenging new dances and refuses to make changes in the choreography of old ones. This potentially interesting, possibly tragic, theme of aging in what is really one of the world's most demanding sports is, however, only briefly touched on.

(7) An argument occurs between the director and one dancer, who hates choreography of a dance he's in, in which men wearing skirts `give birth' -- and the director instantly reverses what he said about how to perform this moment the day before. The director is adamant, the dancer has lost his cool, and the conversation breaks down. He frequently ends unsatisfactory conversations by dismissing his interlocutor. The director's rule is autocratic and rarely challenged. However the company does get mild revenge toward the end in a mock restaging of the season's events at a party.

All this adds up to something so generic and uninteresting as emotional truth or human experience that you are deeply grateful when at least the main dancer character, Neve Campbell, gets hooked up with a cook boyfriend, the intriguing James Franco. You're thankful for one young male movie star in the piece, because the real dancer `actors' - as usual - have very little presence or ability as actors. All James Franco gets to do is smile, kiss the girl, take off his shirt, and break some eggs. He does these things with lots of charm and charisma, but these are just crumbs tossed to us. The point however seems to be that dancers don't have time for much more than quick sex; it's like smoking a cigarette, something squeezed in.

Altman's casts are usually heavy with talent. This time there are only three leads, Campbell, McDowell, and Franco. Ironically only the least used, Franco, has any real appeal.

Ms. Campbell is little more than bustling and workmanlike. She has a few minutes with her pushy stage mother that provide some sense of relationships outside the company, but it's not enough.

You will have a lot of trouble with this movie if you don't like Malcolm McDowell. As the `Italian' company director Alberto Altonelli, he is brusque, bossy, obtrusive -- really just a flaming a**hole with a lot of power to abuse. Is this how dance companies work? Where's the genius? Why does young Franco have more charisma and sex appeal? And what's this about a ceremony in which the blatantly English McDowell gets an award for `honoring the Italian-American community'? Okay; let's pretend that he's Italian. But do we have to pretend he has no English accent? If that weren't bad enough, his little speech about not discouraging their sons from becoming ballet dancers is jarring and crude, like all his speeches: it's the height of ingratitude, and you wonder how anyone so undiplomatic could get money for his company. Is it just possible that McDowell is a jarring and crude actor? His performance is wooden and unsubtle. All he has to qualify for this role is forcefulness. Granted, he has that. But his scenes are nothing but irritations.

This is, at best, a generic treatment of an American ballet company. But it fails even on that level. How come none of the male dancers, not one, is shown to be gay? Isn't that a bit unrealistic about the culture of dance? Why the pretense that they're all straight, vying to have sex with the female dancers in the company?

Neve's partner after their triumph in the rain has a private improv session unwinding to a Bach solo cello suite. It's rather fun - and would have worked better if it had been allowed to run by itself and not been constantly intercut with the scene of Neve in her apartment - a huge Hollywood-style creation right by the `El' with a glam bath. The improvised Bach session makes you realize that Flash Dance was better than this. There was another movie about a dance company, featuring real dancers again, that was better than this. It had a bit more plot, and perhaps better dances; the people seemed a tad more real as people - and yet it wasn't a great movie. Altman's film has spectacular dance sequences at the beginning and the end but they're just staging, not great dance, and they're window dressing to cover up the emptiness of the whole production.

If you love dance and/or Altman you'll doubtless have to see this picture, but you won't be watching a particularly memorable ballet movie or getting Altman even at his average level.

(1) Among the many dance `numbers,' the one that stands out is the first, an outdoor performance featuring the Hollywood actress Neve Campbell (Scream 1,2, and 3, Wild Things), a trained dancer and the force behind the making of the whole film. A thunderstorm comes to buffet the audience and the dancers. The dancers bravely go on and the dance -- so we're told, anyway -- is a triumph. The entire sequence is dominated by a sense of impending disaster. A slippery stage could have meant serious injury. One also wonders about damage to valuable string instruments being played in the open to accompany the dance. All this is extremely distracting and excruciating to watch. Altman does succeed though in giving us a sense of what performances are like from the company's point of view -- struggles with physical problems; successful efforts (at best) to avert disaster.

(2) An injury forces a new lead dancer to give up a role. This happens twice. We realize that dancers constantly face injury, or, as often, are dangerously in denial that they have one.

(3) Another sort of injury prevents a dancer from performing the whole of a `number.' This happens to Neve Campbell at the end of the movie. It's just an arm injury, so not career-threatening, but enough to require a quick replacement by a stand-in.

(4) A young man is replaced, but only for the latter part of a dance he's in -- because his energy seems to flag at that point in the performance. This nonetheless results in a terribly bruised ego for the young man and his union rep promises to lodge a formal protest. We get a sense of the constant threats to the ego in such an arbitrarily run system, along with the surprising news that union redress may be available in such cases.

(5) One of the guys in the company takes a new girlfriend. This time again it's Neve Campbell who's the `injured' one, and at a post-performance celebration she delivers an `I was the last to know' speech to the bad boy. I saw nods of agreement from dancerly-looking audience members during this moment.

(6) The aging female lead dancer - she's 43 - repeatedly protests about too-challenging new dances and refuses to make changes in the choreography of old ones. This potentially interesting, possibly tragic, theme of aging in what is really one of the world's most demanding sports is, however, only briefly touched on.

(7) An argument occurs between the director and one dancer, who hates choreography of a dance he's in, in which men wearing skirts `give birth' -- and the director instantly reverses what he said about how to perform this moment the day before. The director is adamant, the dancer has lost his cool, and the conversation breaks down. He frequently ends unsatisfactory conversations by dismissing his interlocutor. The director's rule is autocratic and rarely challenged. However the company does get mild revenge toward the end in a mock restaging of the season's events at a party.

All this adds up to something so generic and uninteresting as emotional truth or human experience that you are deeply grateful when at least the main dancer character, Neve Campbell, gets hooked up with a cook boyfriend, the intriguing James Franco. You're thankful for one young male movie star in the piece, because the real dancer `actors' - as usual - have very little presence or ability as actors. All James Franco gets to do is smile, kiss the girl, take off his shirt, and break some eggs. He does these things with lots of charm and charisma, but these are just crumbs tossed to us. The point however seems to be that dancers don't have time for much more than quick sex; it's like smoking a cigarette, something squeezed in.

Altman's casts are usually heavy with talent. This time there are only three leads, Campbell, McDowell, and Franco. Ironically only the least used, Franco, has any real appeal.

Ms. Campbell is little more than bustling and workmanlike. She has a few minutes with her pushy stage mother that provide some sense of relationships outside the company, but it's not enough.

You will have a lot of trouble with this movie if you don't like Malcolm McDowell. As the `Italian' company director Alberto Altonelli, he is brusque, bossy, obtrusive -- really just a flaming a**hole with a lot of power to abuse. Is this how dance companies work? Where's the genius? Why does young Franco have more charisma and sex appeal? And what's this about a ceremony in which the blatantly English McDowell gets an award for `honoring the Italian-American community'? Okay; let's pretend that he's Italian. But do we have to pretend he has no English accent? If that weren't bad enough, his little speech about not discouraging their sons from becoming ballet dancers is jarring and crude, like all his speeches: it's the height of ingratitude, and you wonder how anyone so undiplomatic could get money for his company. Is it just possible that McDowell is a jarring and crude actor? His performance is wooden and unsubtle. All he has to qualify for this role is forcefulness. Granted, he has that. But his scenes are nothing but irritations.

This is, at best, a generic treatment of an American ballet company. But it fails even on that level. How come none of the male dancers, not one, is shown to be gay? Isn't that a bit unrealistic about the culture of dance? Why the pretense that they're all straight, vying to have sex with the female dancers in the company?

Neve's partner after their triumph in the rain has a private improv session unwinding to a Bach solo cello suite. It's rather fun - and would have worked better if it had been allowed to run by itself and not been constantly intercut with the scene of Neve in her apartment - a huge Hollywood-style creation right by the `El' with a glam bath. The improvised Bach session makes you realize that Flash Dance was better than this. There was another movie about a dance company, featuring real dancers again, that was better than this. It had a bit more plot, and perhaps better dances; the people seemed a tad more real as people - and yet it wasn't a great movie. Altman's film has spectacular dance sequences at the beginning and the end but they're just staging, not great dance, and they're window dressing to cover up the emptiness of the whole production.

If you love dance and/or Altman you'll doubtless have to see this picture, but you won't be watching a particularly memorable ballet movie or getting Altman even at his average level.

Lets hope that Altman makes films for another 20 years and that he stays as adventuresome as he currently is.

In 'The Long Goodbye' Altman invented a rather new camera stance, literally asking the actors to improvise staging and having the camera discovering them.

It took a few decades for him to get back to such experiments with 'Gosford.' Now he takes it even further with perhaps the purest problem in film cinematography: how do you film dance?

Forget that this features Campbell in a vanity role: she is good enough and doesn't detract. Forget about any modicum of plot: there isn't any. And unlike 'Nashville' or the similarly selfreferential 'Player' there is no cynical commentary.

The commentary itself is selfreferential this time. Yes, this time the center of the film is how 'Mr A' orchestrates movement and images. This is most of all about himself, and is far, far more intelligent and subtle than say, 'Blowup.'

But along the way, you get possibly the best dance experience on film. That's because they've been able to use many cameras. There are not as many as 'Dancer in the Dark,' but each camera dances, engages with the dance and the dance of people and objects around the dance. So we get four layers of dance: the actual ballet, the orchestration of people around the production, the dancing cameras (enhanced by non-radical appearing radical editing) and the dance within the mind of Mr A who encourages, follows and captures them all.

Ted's Evaluation -- 3 of 3: Worth watching.

In 'The Long Goodbye' Altman invented a rather new camera stance, literally asking the actors to improvise staging and having the camera discovering them.

It took a few decades for him to get back to such experiments with 'Gosford.' Now he takes it even further with perhaps the purest problem in film cinematography: how do you film dance?

Forget that this features Campbell in a vanity role: she is good enough and doesn't detract. Forget about any modicum of plot: there isn't any. And unlike 'Nashville' or the similarly selfreferential 'Player' there is no cynical commentary.

The commentary itself is selfreferential this time. Yes, this time the center of the film is how 'Mr A' orchestrates movement and images. This is most of all about himself, and is far, far more intelligent and subtle than say, 'Blowup.'

But along the way, you get possibly the best dance experience on film. That's because they've been able to use many cameras. There are not as many as 'Dancer in the Dark,' but each camera dances, engages with the dance and the dance of people and objects around the dance. So we get four layers of dance: the actual ballet, the orchestration of people around the production, the dancing cameras (enhanced by non-radical appearing radical editing) and the dance within the mind of Mr A who encourages, follows and captures them all.

Ted's Evaluation -- 3 of 3: Worth watching.

I suppose you can call this splendid movie a documentary showing several months in the life of the Joffrey Ballet of Chicago. However, as there are some dramatized elements (albeit to a minimum), you can't technically call it a documentary. And yet, it's more truthful than many "full" documentaries. Completely free from contamination of melodrama, the movie shows us, in a matter-of-fact manner, things behind the stage dedication and sacrifices, lucky breaks that even the top talents sometimes need, experienced performers arguing anainst new ideas, injury and understudy stepping in at a moment's notice, disappointment from being fired, and much more.

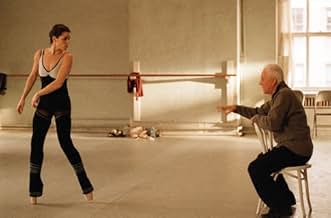

Doing what he does best, master Altman gives you an inconspicuous spot in the rehearsal hall, in the meeting room, back stage, to show you how an idea evolves right from an artist's concept to a successful performance the road that is sometimes painful, sometimes exhilarating and everything in between, the process that affects the lives of the people who are part of the whole. Overlapping dialogue here is not just Altman's artistic and technical trademark, but the way people REALLY speak. Through his amazing deployment of the camera, he also gives the audience a kaleidoscope of events and emotions that are fleeting and fluid, and yet remain with you long after the movie.

In addition to the insight of the documentary, dance lovers will enjoy the generous helping of dance scenes, particularly the outdoor performance in a thunder storm at the beginning. And although personal story is not the point of this movie, the depiction of the relationship between the characters played by Neve Campbell (the dancer) and James Franco (the chef) is wonderful. The scene of their first meeting is a joy to watch she is playing pool by herself and really enjoying it while he, a drink in hand, regards her somewhat stoically at a distance. The two of them are depicted in so many angles, sometimes in the same frame, sometimes separately. This scene is so mesmerizing that you'll forget the passage of time. At long last, they make eye contact and smile. Then, a cut to the next morning in her apartment when they are just waking up, as he offers to cook breakfast for them. An absolutely beautiful sequence.

Campbell and Franco are simply wonderful. The icon of the movie, however, is artistic director of the company Alberto Antonelli , generally known as "Mr A", who comes off larger than life with the flare of Malcolm McDowell, who undoubted is remembered best from "A clockwork orange".

To people who have experienced the joy of stage performance, even in a very modest way of an amateur choir or theatre group, there is the bonus of additional empathy the sometimes not so smooth rehearsals, the panic as the performance approaches and nothing seems to work, the last minute jitters before curtain, the final jubilation when everything miraculously falls into place and the sincere applause of the audience. Such empathy!

Doing what he does best, master Altman gives you an inconspicuous spot in the rehearsal hall, in the meeting room, back stage, to show you how an idea evolves right from an artist's concept to a successful performance the road that is sometimes painful, sometimes exhilarating and everything in between, the process that affects the lives of the people who are part of the whole. Overlapping dialogue here is not just Altman's artistic and technical trademark, but the way people REALLY speak. Through his amazing deployment of the camera, he also gives the audience a kaleidoscope of events and emotions that are fleeting and fluid, and yet remain with you long after the movie.

In addition to the insight of the documentary, dance lovers will enjoy the generous helping of dance scenes, particularly the outdoor performance in a thunder storm at the beginning. And although personal story is not the point of this movie, the depiction of the relationship between the characters played by Neve Campbell (the dancer) and James Franco (the chef) is wonderful. The scene of their first meeting is a joy to watch she is playing pool by herself and really enjoying it while he, a drink in hand, regards her somewhat stoically at a distance. The two of them are depicted in so many angles, sometimes in the same frame, sometimes separately. This scene is so mesmerizing that you'll forget the passage of time. At long last, they make eye contact and smile. Then, a cut to the next morning in her apartment when they are just waking up, as he offers to cook breakfast for them. An absolutely beautiful sequence.

Campbell and Franco are simply wonderful. The icon of the movie, however, is artistic director of the company Alberto Antonelli , generally known as "Mr A", who comes off larger than life with the flare of Malcolm McDowell, who undoubted is remembered best from "A clockwork orange".

To people who have experienced the joy of stage performance, even in a very modest way of an amateur choir or theatre group, there is the bonus of additional empathy the sometimes not so smooth rehearsals, the panic as the performance approaches and nothing seems to work, the last minute jitters before curtain, the final jubilation when everything miraculously falls into place and the sincere applause of the audience. Such empathy!

Ugh. The problem with The Company is that it's not a Robert Altman film. His touch is evident in the filmmaking and fly-on-the-Wall feel of the movie, but it's not his movie. It's Neve Campbell's, who wrote, produced, and starred in it. Campbell spent years with the national ballet and this movie was a labor of that passion. However, that is precisely where it goes wrong. It shoots for the wrong audience. Dancers will likely love this movie but they are the choir. They know how a dance company works, the back dealing and politics. They don't need this movie. The rest of us don't learn anything, or at least learn just enough to know that professional dancing is a horrible way to live. The dancing was beautiful, including Neve's, although she doesn't look quite as polished as her back ups in the company, but the characters were shallow and you are never given anything to grab onto to care about any of them. The only ones you root for the ones who are injured or fired so they can get out of that horrible horrible place. Such a disappointment on so many levels. The only thing that does come off well is the Joffrey. You actually leave the theater wondering if the Ballet company underwrote the production as a marketing expense.

"The Company" is a lovely commercial for the Joffrey Ballet of Chicago (for New Yorkers this is in fact the same modern ballet company that used to be based at City Center but left the competitive dance fund raising environment here to have the stage to itself in Chicago).

A labor of love for producer/story writer/star/former dancer Neve Campbell, she was determined to make the first film about a whole company, not just using the dance world for a backdrop of individual melodrama, and with long passages of actual performances. So she brought in the primo director of ensembles, Robert Altman. But clearly she made compromises to get the film made that put his creativity as a director in a straight jacket and only lets his trademark talents fleetingly shine through.

The key was getting the Joffrey's cooperation and I can only imagine the tough negotiations that resulted in this pretty much being a whitewash of the ballet world, or of any creative endeavor, in sharp contrast to the behind-the-scenes reality shows "Project Greenlight" on HBO or "The Fire Within" about Cirque du Soleil's "Varekai" that was on Bravo. I surmise a long list of thou shalt not's that appear to include items such as:

-- no views of the non-artistic administrators, board, or fund raisers (there's a passing exhortation to a flashy choreographer Robet Desrosiers to stay within the budget, but he gets the complicated costumes and sets he wants anyway);

-- no homosexual relationships (there's a passing reference to the dancers AIDS has taken including "Bob", which cognoscenti have to know refers to the company's founder Robert Jeffrey, and Malcolm McDowall as the egotistical artistic director "Alberto Antonelli," a stand-in presumably for current company director Gerald Arpino, urges fellow Italian-American men not to make their boys, like he had to, "hide their ballet shoes");

-- no eating disorders (we do twice hear "Mr. A," half-jokingly, urge the company to eat salads and vegetables and there's one fast, quiet exchange in passing that I think was about diet pills);

-- blame dancers' problems on dysfunctional parents and mentors, recalling that vivid song from "A Chorus Line" - "Everything was beautiful at the ballet" as dancers seek to escape messy situations through temporary perfect beauty.

Altman does get to assert his artistic priorities in a few ways. He effectively seizes on the ageism in dance, showing that it's not just the tyranny of aging bodies, as would affect any athlete, but that dancers with experience speak up for themselves and are more difficult to control in a viciously autocratic environment than ambitious, financially desperate, and, literally, pliable young dancers.

It's also the first time I've seen a camera expose the swarm of acolyte assistants to the director, revealing them as ex-dancers whom "Mr. A" still dismissively calls "babies" and who resent the new stars even as they dance vicariously through them.

The other beautiful Altman touch is when the significant character developments take place not center stage in a crowd but through a look or line happening way in the corner of the screen, like the expression on James Franco, as Cambell's chef beau, when she avoids introducing him to her family amidst a rush of congratulators.

But visually and musically the Joffrey is a wonderful choice, as the choreographers represented range from Arpino to Alwin Nikolais to Laura Dean and MOMIX. A centerpiece danced by Campbell is a sexy Lar Lubovitch pas de deux to the signature song "My Funny Valentine" which is used as a leitmotif, for reasons that still seem murky to me after hearing Altman explain why on "Charlie Rose," throughout the film in versions also by Elvis Costello, Chet Baker, and the Kronos Quartet. The music ranges from classical to jazz to the ethereal pop of Julee Cruise, Mark O'Connor's in-between "Appalachia Waltz", and the lovely score by Van Dyke Parks.

A labor of love for producer/story writer/star/former dancer Neve Campbell, she was determined to make the first film about a whole company, not just using the dance world for a backdrop of individual melodrama, and with long passages of actual performances. So she brought in the primo director of ensembles, Robert Altman. But clearly she made compromises to get the film made that put his creativity as a director in a straight jacket and only lets his trademark talents fleetingly shine through.

The key was getting the Joffrey's cooperation and I can only imagine the tough negotiations that resulted in this pretty much being a whitewash of the ballet world, or of any creative endeavor, in sharp contrast to the behind-the-scenes reality shows "Project Greenlight" on HBO or "The Fire Within" about Cirque du Soleil's "Varekai" that was on Bravo. I surmise a long list of thou shalt not's that appear to include items such as:

-- no views of the non-artistic administrators, board, or fund raisers (there's a passing exhortation to a flashy choreographer Robet Desrosiers to stay within the budget, but he gets the complicated costumes and sets he wants anyway);

-- no homosexual relationships (there's a passing reference to the dancers AIDS has taken including "Bob", which cognoscenti have to know refers to the company's founder Robert Jeffrey, and Malcolm McDowall as the egotistical artistic director "Alberto Antonelli," a stand-in presumably for current company director Gerald Arpino, urges fellow Italian-American men not to make their boys, like he had to, "hide their ballet shoes");

-- no eating disorders (we do twice hear "Mr. A," half-jokingly, urge the company to eat salads and vegetables and there's one fast, quiet exchange in passing that I think was about diet pills);

-- blame dancers' problems on dysfunctional parents and mentors, recalling that vivid song from "A Chorus Line" - "Everything was beautiful at the ballet" as dancers seek to escape messy situations through temporary perfect beauty.

Altman does get to assert his artistic priorities in a few ways. He effectively seizes on the ageism in dance, showing that it's not just the tyranny of aging bodies, as would affect any athlete, but that dancers with experience speak up for themselves and are more difficult to control in a viciously autocratic environment than ambitious, financially desperate, and, literally, pliable young dancers.

It's also the first time I've seen a camera expose the swarm of acolyte assistants to the director, revealing them as ex-dancers whom "Mr. A" still dismissively calls "babies" and who resent the new stars even as they dance vicariously through them.

The other beautiful Altman touch is when the significant character developments take place not center stage in a crowd but through a look or line happening way in the corner of the screen, like the expression on James Franco, as Cambell's chef beau, when she avoids introducing him to her family amidst a rush of congratulators.

But visually and musically the Joffrey is a wonderful choice, as the choreographers represented range from Arpino to Alwin Nikolais to Laura Dean and MOMIX. A centerpiece danced by Campbell is a sexy Lar Lubovitch pas de deux to the signature song "My Funny Valentine" which is used as a leitmotif, for reasons that still seem murky to me after hearing Altman explain why on "Charlie Rose," throughout the film in versions also by Elvis Costello, Chet Baker, and the Kronos Quartet. The music ranges from classical to jazz to the ethereal pop of Julee Cruise, Mark O'Connor's in-between "Appalachia Waltz", and the lovely score by Van Dyke Parks.

Wusstest du schon

- WissenswertesNeve Campbell lost thousands of dollars of her own money to ensure that her fellow cast members received their wages.

- PatzerAt about 1:10 while counting during a rehearsal, Harriet skips the 6th count of 8.

- Zitate

Alberto Antonelli: Ry, honey, let's scramble some ideas, instead of some asshole who contradicts me.

- Crazy CreditsAfter the closing credits begin rolling, the dancers continue to take their final bows, and the audience continues to applaud.

Top-Auswahl

Melde dich zum Bewerten an und greife auf die Watchlist für personalisierte Empfehlungen zu.

- How long is The Company?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Erscheinungsdatum

- Herkunftsländer

- Offizielle Standorte

- Sprache

- Auch bekannt als

- The Company

- Drehorte

- Produktionsfirmen

- Weitere beteiligte Unternehmen bei IMDbPro anzeigen

Box Office

- Budget

- 15.000.000 $ (geschätzt)

- Bruttoertrag in den USA und Kanada

- 2.283.914 $

- Eröffnungswochenende in den USA und in Kanada

- 93.776 $

- 28. Dez. 2003

- Weltweiter Bruttoertrag

- 6.415.017 $

- Laufzeit1 Stunde 52 Minuten

- Farbe

- Sound-Mix

- Seitenverhältnis

- 2.35 : 1

Zu dieser Seite beitragen

Bearbeitung vorschlagen oder fehlenden Inhalt hinzufügen