IMDb-BEWERTUNG

6,9/10

3786

IHRE BEWERTUNG

Füge eine Handlung in deiner Sprache hinzuA swordsmith trains his friend's orphaned son. The boy seeks revenge for his father's murder but loses an arm rescuing the swordsmith's daughter. A hermit girl nurses him, and he learns swor... Alles lesenA swordsmith trains his friend's orphaned son. The boy seeks revenge for his father's murder but loses an arm rescuing the swordsmith's daughter. A hermit girl nurses him, and he learns swordsmanship with his father's broken sword.A swordsmith trains his friend's orphaned son. The boy seeks revenge for his father's murder but loses an arm rescuing the swordsmith's daughter. A hermit girl nurses him, and he learns swordsmanship with his father's broken sword.

- Auszeichnungen

- 1 Gewinn & 2 Nominierungen insgesamt

Xiong Xinxin

- Fei Lung

- (as Xin Xin Xiong)

Collin Chou

- Fast Sabre (Guest star)

- (as Sing Ngai)

Empfohlene Bewertungen

Apparently, this is quite difficult to see in theatres. I managed to, but it is on video. I imagine that on video, the subtitles are as difficult to read as the ones in "A Chinese Ghost Story" (Another Hark title). Many of the fight scenes are, like the other title, shot on a set in near total darkness with some artificial light as "moonlight". Again, on a screen, beautiful, but on video, a bit hard to see. There is A LOT of fighting, chopped arms legs and heads. (What do you expect, with the action centered around a knife/sword factory?) It's so violent that after a while I found myself laughing to relieve the tension. And the spewing blood can be comical. Like many of these movies, even the "good" guys have questionable motives.

I was interested in this because I'd read that Hark stopped production in the middle because of one of the actress's complaints and rewrote it from a woman's perspective. Still, the main female character is whiny, silly and sheltered, little more than a typical HK plot device to get fights going. I found her character very annoying.

Plot: 4 of 10, fight scenes 8 of 10 IF you can see them on a large screen. Subtitles are lousy, but not really necessary.

I was interested in this because I'd read that Hark stopped production in the middle because of one of the actress's complaints and rewrote it from a woman's perspective. Still, the main female character is whiny, silly and sheltered, little more than a typical HK plot device to get fights going. I found her character very annoying.

Plot: 4 of 10, fight scenes 8 of 10 IF you can see them on a large screen. Subtitles are lousy, but not really necessary.

10Manny-54

I must tell you that i'm a little bit shocked and really can't believe that nearly no one has fully grasped this one of the most meaningful and prominent films of our time. Everyone criticizing the surface and the effectiveness but in fact truly missing the point what this film is actually about! A little bit of analysis: At first i have to point out that THE BLADE is enormously similar to Sam Peckinpah's shocking masterpiece from the 1971 STRAW DOGS (and a bit to his companion A Clockwork Orange) both films depicting violence as a natural element or something habitual, in other words the film is implying resonating message that we're just animals with big brains and endless violence we can not be rid of. Blade, SD and ACO are fictitious, ambiguous, allegorical and shocking but in reality are very symbolical and showing the true face of humanity that we are all so scared of! I strongly believe there's also somewhere in those films actually the answer if the peace in the world is even feasible. The Blade has so many symbolical meanings that even the fictional violent world the movie takes place in, only prompting us to apply it to ours. Why? Because the world we're living in is also about the survival like in the film (where is everything only simplified and exaggerated for us just to see the true reality of our world, that's the whole trick). The paradoxical, inadvertent and sometimes very futile violence in the film breeding and producing another violence (e.g. On's revenge for his dead father (where's no redemption) or those exposed little kids watching the bloody fight between that monk and bandits, which is if you think about it enormously provocative vestige of how the world must be so cruel when even a monk has become such a violent beast who then will only manifest that little hint of his smile at those small kids as some kind of a symbol of an inspiration for them - which is very morally inverted). Very common thing in our world is also an involuntary or unconscious act that only brings about another killing and death to others - examples: Ding On inadvertently kills the prostitute Iron Head brought to himself, Ling's father is in fact responsible for a lot of hurt to come when he told Ding On the truth about his father. Chiu Man Cheuk's Ding On initially was against the revenge (mind you the scene after the monk is dead) but Iron Head was all for it who also inadvertently divulged the place where they are from to bandits which would lead to another killing at the end at the Foundry, and etc.. The film even mentions things like buying and selling and at the same time showing the dog approaching some chunk of meat planted right in the big bear jaggy trap which ultimately kills him, the scenes like this are only exaggerated just to give us an idea and feeling of how hard it is to make it through in this world but Tsui Hark de-facto made it clear enough when increased or leveled up the whole hardness of the life in this film and showed us the way how to survive which systematically should be only motivating and inspiring for the viewers of this film. Every time you watch this movie you can find more and more connections between this demented world and ours, which is also the powerful and timeless element of The Blade.

Not Ding On or Iron Head, it was in fact Ling all along who's the most important character (not so strange that the whole film is also off her point of view) as she was also the only one left at the end of the movie still feeling the love for other people but as we see it's late because there's already no one to return her love. What is so paradoxical is that everyone (save for her) in the film was actually neglecting the most important and powerful weapon for this violent world "love", what they were doing was absolutely futile, fruitless, nothing for anyone things which means they ended up as individuals with the complete lack of affection and love for anyone and by this ended up only producing another ceaseless violence that would lead only to downfall of the whole mankind, there was no end to this. So everyone could take the film Blade as the warning or advice - what is virtually the most important for our world!!

I have a more extensive analysis (too long for these comments) of this masterpiece, check out my thread here on The Blade message board!

Not Ding On or Iron Head, it was in fact Ling all along who's the most important character (not so strange that the whole film is also off her point of view) as she was also the only one left at the end of the movie still feeling the love for other people but as we see it's late because there's already no one to return her love. What is so paradoxical is that everyone (save for her) in the film was actually neglecting the most important and powerful weapon for this violent world "love", what they were doing was absolutely futile, fruitless, nothing for anyone things which means they ended up as individuals with the complete lack of affection and love for anyone and by this ended up only producing another ceaseless violence that would lead only to downfall of the whole mankind, there was no end to this. So everyone could take the film Blade as the warning or advice - what is virtually the most important for our world!!

I have a more extensive analysis (too long for these comments) of this masterpiece, check out my thread here on The Blade message board!

9zdac

The Blade is a whirlwind of blood, dust, and psychedelic colour. Beneath its rough, brutal appearance lies an uncompromising and technically evolved offering from Hong Kong's prolific director/producer giant Tsui Hark. Based on the old-school kung-fu classic The One-Armed Swordsman, The Blade tells the story of a young man adopted by a renowned blacksmith, who discovers that his true father was killed by superstitiously powerful bandit named Lung, "who it is said can fly!".

When he impulsively goes out seeking revenge, he runs afoul of a gang of desert scum and loses his right arm in the encounter. Ashamed, he goes into hiding but after finding an broken weapon and the tatters of an old swordfighting manual, he begins to come to terms with his self-loathing, and eventually learns to compensate for his loss. With half a sword, half a technique, and still one arm short of a pair, he returns to his old home to confront both his past and the man who murdered his father.

A simple tale of vengeful perseverance here gets a nihilistic gritty art-house treatment. The action takes place in an amoral, almost post-apocalyptic desert landscape. Hark's camera speeds around with abandon, capturing both the bleak setting and the lush expressive palette of the characters' internal emotional landscape. In terms of camera style and visual dynamism, this is Hark's most adventurous film. Although seemingly frantic, it is never random. The cinematography bears a meticulous attention to detail, and the editing has a razor-sharp rhythm of its own.

There's a lot going on under the surface here. The simple story is fleshed out with a dark sensuality. Along with themes of surmounting obstacles through hard work, and misplaced honour in a harsh and selfish world (kung fu movie essentials), we find commentary on lust, gender, and simple pragmatism as well. Early on, a Shaolin monk, icon of heroism, meets a grisly, inglorious end, signifying that this is not just another heroic martial-arts fantasy. And yet heroism survives, in the form of a crippled man with a broken, cleaver-like weapon... just one more way The Blade offers new twists on old conventions.

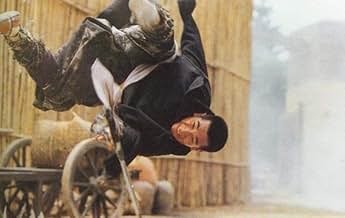

This being a Hong Kong martial-arts movie, the action is to be noted. Where fluid idealized wushu forms might normally prevail, a certain street-level grittiness and desperation takes hold. Even when characters are performing incredible feats, you find yourself thinking "So this is what kung-fu fighting was really like."

Although Chiu Cheuk and villainous Xiong Xin Xin can certainly deliver spectacular physical displays (as seen in Hark's later Once Upon A Time in China films), in The Blade the camera and editing take the lead. While some reviewers tend to forget the "cinema" part of "martial arts cinema", and complain that much of the action is concealed by the breakneck editing and moving camera, there is still an impressive amount of wushu on display in this film, and the frenzied cutting serves to heighten the excitement and the abilities of the performers, even without implied supernatural powers or gratuitous wire stunts. As a result, the final 15 minutes of this movie frame possibly some of the most furious, breathless, vicious fight sequences in cinema history.

Believe it!

When he impulsively goes out seeking revenge, he runs afoul of a gang of desert scum and loses his right arm in the encounter. Ashamed, he goes into hiding but after finding an broken weapon and the tatters of an old swordfighting manual, he begins to come to terms with his self-loathing, and eventually learns to compensate for his loss. With half a sword, half a technique, and still one arm short of a pair, he returns to his old home to confront both his past and the man who murdered his father.

A simple tale of vengeful perseverance here gets a nihilistic gritty art-house treatment. The action takes place in an amoral, almost post-apocalyptic desert landscape. Hark's camera speeds around with abandon, capturing both the bleak setting and the lush expressive palette of the characters' internal emotional landscape. In terms of camera style and visual dynamism, this is Hark's most adventurous film. Although seemingly frantic, it is never random. The cinematography bears a meticulous attention to detail, and the editing has a razor-sharp rhythm of its own.

There's a lot going on under the surface here. The simple story is fleshed out with a dark sensuality. Along with themes of surmounting obstacles through hard work, and misplaced honour in a harsh and selfish world (kung fu movie essentials), we find commentary on lust, gender, and simple pragmatism as well. Early on, a Shaolin monk, icon of heroism, meets a grisly, inglorious end, signifying that this is not just another heroic martial-arts fantasy. And yet heroism survives, in the form of a crippled man with a broken, cleaver-like weapon... just one more way The Blade offers new twists on old conventions.

This being a Hong Kong martial-arts movie, the action is to be noted. Where fluid idealized wushu forms might normally prevail, a certain street-level grittiness and desperation takes hold. Even when characters are performing incredible feats, you find yourself thinking "So this is what kung-fu fighting was really like."

Although Chiu Cheuk and villainous Xiong Xin Xin can certainly deliver spectacular physical displays (as seen in Hark's later Once Upon A Time in China films), in The Blade the camera and editing take the lead. While some reviewers tend to forget the "cinema" part of "martial arts cinema", and complain that much of the action is concealed by the breakneck editing and moving camera, there is still an impressive amount of wushu on display in this film, and the frenzied cutting serves to heighten the excitement and the abilities of the performers, even without implied supernatural powers or gratuitous wire stunts. As a result, the final 15 minutes of this movie frame possibly some of the most furious, breathless, vicious fight sequences in cinema history.

Believe it!

The great thing about this film (and the sort of thing that upsets people who like seeing martial arts fights where you can see every kick and every punch) is that most of the fighting is just blurs of motion punctuated by shouting and clashing blades. This is what I love in HK fantasies: fight scenes that are so incomprehensible you're left going: huh?

Tsui Hark's best example is Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain, where the viewer has to actually fill in the blanks for themselves. It's edited in such a way that that the film we see feels like only a portion of the story. In some contexts this technique would be stupid, but in fantasy it's wonderful. It's the inverse of the computer graphics bare-all approach, and it's lucky that we had the HK film industry to provide an alternative to Hollywood in this regard. (I say had, because, since Storm Riders, cg in HK is more prevalent than before.)

This approach to fight scenes is impressionistic, and with the final fightscene in Dao it's almost operatic. At no stage do you get a feeling that the fight is actually rational. The use of sound and music in the film is also wonderful, especially in the menacing flashback scene. It's hard to think of a more effective way of setting up a backstory, and gives new life to that tired old cliche, the revenge story.

So that's all good. Sometimes, however, the impressionism gets a bit out of hand. Things take on a Wong Kar Wai pretentiousness, like the horrible Ashes of time, where Leslie Cheung sits around feeling sorry for himself for no appreciable reason. In Dao, the voiceover of the female character gets really annoying. Her mutterings only really serve to remind us she is there, as she has only one pivotal scene in the film (where tells the hero his origin story).

The film is also a bit over-bloody for my taste, but it certainly leaves one with no illusions about the brutalness of the world in which the film is set.

Dao is one of those films that is so strange and vivid it leaves a strong resonance with the viewer long after it is over. It has faults by the barrel, but I'd rather have it and Tsui Hark with us than a legion of James Camerons and Roland Emmerichs.

Tsui Hark's best example is Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain, where the viewer has to actually fill in the blanks for themselves. It's edited in such a way that that the film we see feels like only a portion of the story. In some contexts this technique would be stupid, but in fantasy it's wonderful. It's the inverse of the computer graphics bare-all approach, and it's lucky that we had the HK film industry to provide an alternative to Hollywood in this regard. (I say had, because, since Storm Riders, cg in HK is more prevalent than before.)

This approach to fight scenes is impressionistic, and with the final fightscene in Dao it's almost operatic. At no stage do you get a feeling that the fight is actually rational. The use of sound and music in the film is also wonderful, especially in the menacing flashback scene. It's hard to think of a more effective way of setting up a backstory, and gives new life to that tired old cliche, the revenge story.

So that's all good. Sometimes, however, the impressionism gets a bit out of hand. Things take on a Wong Kar Wai pretentiousness, like the horrible Ashes of time, where Leslie Cheung sits around feeling sorry for himself for no appreciable reason. In Dao, the voiceover of the female character gets really annoying. Her mutterings only really serve to remind us she is there, as she has only one pivotal scene in the film (where tells the hero his origin story).

The film is also a bit over-bloody for my taste, but it certainly leaves one with no illusions about the brutalness of the world in which the film is set.

Dao is one of those films that is so strange and vivid it leaves a strong resonance with the viewer long after it is over. It has faults by the barrel, but I'd rather have it and Tsui Hark with us than a legion of James Camerons and Roland Emmerichs.

This movie was the one of the first true martial artist films I have seen. Since which I have collected a fine library and yet this one still stands out for the story line. A very impressive movie that managed to keep me in rapture during the whole scenario. I would give a big recommendation to any who appreciate martial artist films or just action films to take a look at this one. Even though the movie as I saw it was fairly dark that is easily looked over as the story line pulls you in.

Wusstest du schon

- WissenswertesOne of Quentin Tarantino's 20 Favourite Movies from 1992 to 2009.

- PatzerThe tattoos on Fei Lung's chest disappear when Ding On throws the blade at his throat in the finale.

- VerbindungenFeatured in Video Buck: TOP 13: Las mejores películas de artes marciales (2017)

Top-Auswahl

Melde dich zum Bewerten an und greife auf die Watchlist für personalisierte Empfehlungen zu.

- How long is The Blade?Powered by Alexa

Details

Zu dieser Seite beitragen

Bearbeitung vorschlagen oder fehlenden Inhalt hinzufügen