Ein bescheidener Büroangestellter wird verhaftet und vor Gericht gebracht, jedoch niemals über den Anklagegrund aufgeklärt.Ein bescheidener Büroangestellter wird verhaftet und vor Gericht gebracht, jedoch niemals über den Anklagegrund aufgeklärt.Ein bescheidener Büroangestellter wird verhaftet und vor Gericht gebracht, jedoch niemals über den Anklagegrund aufgeklärt.

- Regie

- Drehbuch

- Hauptbesetzung

- Auszeichnungen

- 2 Gewinne & 2 Nominierungen insgesamt

- First Assistant Inspector

- (as William Kearns)

- Man in Leather

- (as Karl Studer)

Empfohlene Bewertungen

Josef K literally awakes in the first scene, to a nightmare that he cannot understand, because his own sense of justice refuses to let him understand it. This is Josef K's downfall. There are survivors in the world painted by this film, grim survivors to be sure, but survivors none the less. Josef K is not one of them.

Josef K, in the context that surrounds him in this film, is dysfunctional. He has neither the character nor the experience to survive in his world. He seems oblivious to the lunacy of his environment and strives for something so completely alien, that one wonders where and how he even conceived of his morale code, given the world he lives in.

This of course, leads to terrific drama and an odd tension for the viewer throughout the entire film. That tension springs from the dichotomy of the film, Josef K's idealism vs. the cruel reality all around him. Perhaps more specifically the tension arises from Josef K's struggle for logic and reason in a world gone haywire with paranoia and corruption.

One of the minor but important strengths of this film is the encapsulation of its theme within the 2-minute anecdote that starts the picture. This prologue uses stark drawings on a wheel to transition from scene to scene and is both a riddle and a parable. It is accompanied by a sinister cello and a deep, cold narration by Orson Welles. The anecdote in the prologue is a tale of a man who 'seeks admittance to the law'. The riddle that is laid before him ends in death and with the realization that the man wasted his life, seeking a universal truth, to a very personal question.

Much later in the film, the character of the Advocate tries to retell the chilling prologue to Josef K. Josef however, dismisses the fairy-tale immediately. Refusing to hear its lesson and how it applies to his predicament. The advocate rightly notes, from the prologue: 'it has been observed that the man came to the law of his own free will'. What I believe Orson Welles is telling us, in this scene, is he personally believes Josef K's character to be guilty. Josef is not guilty of a crime to be sure, but he is guilty in his conscience. Josef's wretched self-righteousness and guilt-complex is ugly, even within the context of all the injustice, corruption and abuse that surround him.

Josef is weak, stubborn and oblivious and I believe Orson tells us subtly, that perhaps he deserves to die. What is also left unsaid by the Advocate is the man in the prologue willingly submitted himself to the lunacy that became his death. The man felt it better to live chained to an ideal, that to roam free in an unjust world. If there is a crime Josef K is guilty of, then that is likely it.

I have never read the novel, but I believe Josef K, is a much more tragic figure in Kafka's eyes. In the eyes of Orson Welles - it's apparent to me that Orson Welles considers Josef K to be neither tragic nor overly heroic.

While it may contrast strikingly with Kafka's intention, I think Welles tries to illustrate somewhat that Josef K, is not a complete victim. While Josef's surroundings are nightmarish beyond belief, Josef never adapts to them. He never learns how to survive or worse, refuses to learn how to survive. He judges his world but he hardly ever truly interacts with it and he immediately becomes distracted whenever he feels someone has transgressed his moral view of things.

While the actions of Josef K are noble and we sympathize with his plight, you feel little remorse for his eventual death, because Josef quite simply just does not belong. Like the creature at the end of metamorphosis, an innocent thing, is perhaps best left to die, because it is alien to its environment.

Like all good work, that interpretation of mine is open to a lot of debate. Which is another great feature of this film, it provokes a reaction and that reaction can help you understand more about yourself and your current surroundings.

I think this is strong work. Orson Welles finds ways to delight your eyes on screen. Some of the performances like Romy Schneider's performance as the mistress of the Advocate are seductive and chilling.

It is interesting that women in this film are perverted, contorted and shallow. The perversion of society in Josef K's world is so pervasive that his own 16-year-old cousin cannot even visit him, without suspicion from his co-workers. Even sex and passion in this world is twisted into secrecy, innuendo and fear. The only true female survivors in this film are women who willingly cast themselves as supplicants to men of power and intrigue. While this message may affront those who are sensitive, it adds another element to the nightmare that makes this film so strong.

The film has a similar parallel to the Bicycle Thief in my opinion. The protagonist is sympathetic but is surrounded by injustice and cruelty that shreds his very existence. In both films, no amount of effort on the protagonist's behalf will solve his dilemma. Both characters struggle to come to terms with their tragic plight. Like Antonio, Josef K's quest is futile and his only salvation is acceptance. Unlike Antonio however, Josef K never truly transforms, he will not sink to the same level as the world around him. This is why we feel so sorry for Antonio at the end of the Bicycle Thief but see the Trial's ending as more inevitable than tragic.

It is sometimes hard to feel sorry for a martyr who wears his thorny crown so smugly. This is where the protagonist of Josef and Antonio (Bicycle Thief) depart. Josef willingly becomes a self-righteous martyr, while Antonio chooses life, even at the expense of his dignity.

The logic of this film is the logic of a dream and a nightmare. The Trial is a moral nightmare - a world where the only options for survival are: lies, hypocrisy and servitude. A sacrifice, Josef K, refuses to make and so his door closes, forever.

In 1962, Welles was struggling through his locust years. Having long since alienated himself from Hollywood's money, he was living a vagabond life in Europe, flitting back and forth across the continent to scrape funds together, plan stage productions which hardly ever came to fruition, and sleepwalk through a dozen cameo roles in other people's films. The critical and financial catastrophe of 'Chimes' was hanging over him like a pall, and he had far too many distractions - squabbles with his Irish partners, tax bills in London and potentially ruinous law suits to stave off. With all this to contend with, he was still sporadically shooting portions of "Don Quixote" in Spain, a stuttering project that was by now in its sixth year of filming. Welles was desperately short of money, and as his biographer Higham puts it, "he could manage almost anything except austerity".

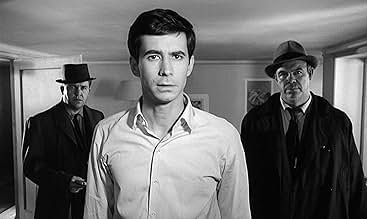

A harmless, inconsequential clerk wakes up one morning to find himself accused of something (he never discovers what). Secret policemen enter his bedroom and subject him to a frightening interrogation in which every answer provokes a new line of questioning. This is psychological torture, the mind's innate sense of justice constantly probing for some higher reference-point, some appeal to fairness, when in fact none exists. Josef K returns repeatedly to the obvious question, "But what have I done?" But there are no rules of justice here, no recourse to an autonomous code of law. "You have the unmitigated gall to pretend you don't know?"

A cry of anguish from the individual who finds himself overwhelmed by soulless bureaucracy, "The Trial" is a deeply personal statement by Welles, and as Higham puts it, "a symbol, if there ever was one, of his own career". Welles had been the enfant terrible whose erratic genius had alienated the big Hollywood studios. Cut off from the big money, he was to spend the subsequent forty years globetrotting aimlessly, picking up work as best he could.

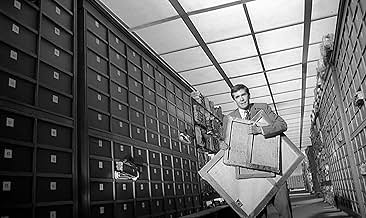

Autobiographical elements of Kafka's own life, contained in "The Trial", are given prominence in the film. Austria-Hungary launched World War One in the same year that Kafka began work on the novel. Ironically, the limited war against Bosnia, intended to restore Austria's international credibility, turned into a conflagration bigger and more horrific than anything previously experienced on earth, and set in train the global violence which was to characterise the twentieth century. It also destroyed Austria-Hungary. Welles closes this story of 1914 with an image of nuclear catastrophe, stressing the oneness of the century's horror. Kafka was bullied by his father, and reference is made in the course of the film to K's sense of filial guilt. The office is depressing and demeaning, echoing Kafka's own experiences as a clerk in a bloated bureaucracy.

The State is remorseless and pitiless, grinding down and perverting even the strongest of human bonds, those of familial and sexual love. K is forced to reject his little cousin Irmie (Maydra Shore), who has to remain 'outside'. Later, an allegation of sexual impropriety concerning Irmie arises. Any magnanimity towards another is interpreted by the authorities as a denunciation. The torture scenes involving the secret policemen are the most disturbing part of the film, both because K realises how his own protests have borne poisoinous fruit, and because of the grinning obsequiousness of the victims. The State turns its problems into spineless curs who acquiesce in their own degradation.

Not only does K find himself becoming an accuser: he even assumes the role of interrogator, questioning Bloch and the Defendants. Anyone who is not a keyholder within the pitiless apparatus of The State cannot help but take on its deadly pallor. Keys are important. Leni, the Court Guard and Zitorelli are empowered through possessing keys. They are a corrupt priesthood in this cult of political disease.

Kafka's experiences with women were deeply ambivalent. He had many intense relationships in his life, none of which proved satisfactory. His book treats women as both temptresses and objects of loathing. Welles follows this line, the women being desirable guide-figures and also deformed monstrosities. The trunk-carrier, Lena and the hunchback girl all have bodily malformations.

Welles shot most of the film in Zagreb, capturing strikingly the two clashing styles of architecture of Mittel-Europa, overblown ugly Habsburg baroque and drab communist functionalism. It is as if the Prague of Mozart cannot help but decay into the Prague of Krushchev. "Ostensibly free" is the best K can hope for, and 'ostensibly individual' is our optimum condition, as the shadows of the Stalinist apartment blocks crowd in on us.

I don't believe that Kafka ever published The Trial during his lifetime. In his will he left instructions that all his literary manuscripts should be destroyed after his death. In what was, perhaps, the final irony of Kafka's life, it was only the disobedience of the executor of the writer's estate that made the peculiarly paranoid world Kafka had created available to the public at all.

See this film and, afterwords, try to get a peaceful night's sleep.

Wusstest du schon

- WissenswertesIn May '62, while filming, Jeanne Moreau suffered a slight nervous breakdown due to the stifling atmosphere of the film.

- PatzerWhen Josef K. follows Hilda being carried out of the large trial room/hall by the law student, he hastily grabs and throws on his suit jacket. In the succeeding scenes, the jacket's buttons which are buttoned change.

- Zitate

[first lines]

Narrator: Before the law, there stands a guard. A man comes from the country, begging admittance to the law. But the guard cannot admit him. May he hope to enter at a later time? That is possible, said the guard. The man tries to peer through the entrance. He'd been taught that the law was to be accessible to every man. "Do not attempt to enter without my permission", says the guard. I am very powerful. Yet I am the least of all the guards. From hall to hall, door after door, each guard is more powerful than the last. By the guard's permission, the man sits by the side of the door, and there he waits. For years, he waits. Everything he has, he gives away in the hope of bribing the guard, who never fails to say to him "I take what you give me only so that you will not feel that you left something undone." Keeping his watch during the long years, the man has come to know even the fleas on the guard's fur collar. Growing childish in old age, he begs the fleas to persuade the guard to change his mind and allow him to enter. His sight has dimmed, but in the darkness he perceives a radiance streaming immortally from the door of the law. And now, before he dies, all he's experienced condenses into one question, a question he's never asked. He beckons the guard. Says the guard, "You are insatiable! What is it now?" Says the man, "Every man strives to attain the law. How is it then that in all these years, no one else has ever come here, seeking admittance?" His hearing has failed, so the guard yells into his ear. "Nobody else but you could ever have obtained admittance. No one else could enter this door! This door was intended only for you! And now, I'm going to close it." This tale is told during the story called "The Trial". It's been said that the logic of this story is the logic of a dream... a nightmare.

- Crazy CreditsThe end cast credits are read over by Orson Welles without titles (though the actors are read in a different order from their listing on the screen).

- Alternative VersionenThe short version cut the opening pin screen sequence and also deleted and rearranged a number of scenes.

- VerbindungenFeatured in The Queen of Sheba Meets the Atom Man (1963)

- SoundtracksAdagio D'Albinoni

Interprété par André Girard (as A. Girard) et Orchestre de l'Association des Concerts Colonne

Arranged by Jean Ledrut

Music by Tomaso Albinoni (T.Albinoni)

Publisher: S.l. : Philips, 1962.

Top-Auswahl

Details

- Erscheinungsdatum

- Herkunftsländer

- Offizieller Standort

- Sprache

- Auch bekannt als

- The Trial

- Drehorte

- 240 Grada Vukovara Street, Zagreb, Kroatien(Joseph K. and old lady lugging a trunk)

- Produktionsfirmen

- Weitere beteiligte Unternehmen bei IMDbPro anzeigen

Box Office

- Budget

- 1.300.000 $ (geschätzt)

- Bruttoertrag in den USA und Kanada

- 93.533 $

- Eröffnungswochenende in den USA und in Kanada

- 7.280 $

- 11. Dez. 2022

- Weltweiter Bruttoertrag

- 94.243 $

- Laufzeit1 Stunde 59 Minuten

- Farbe

- Seitenverhältnis

- 1.66 : 1