IMDb-BEWERTUNG

6,7/10

2149

IHRE BEWERTUNG

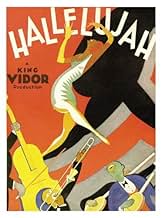

Füge eine Handlung in deiner Sprache hinzuA sharecropper decides to become a preacher after falling for a vamp from the city.A sharecropper decides to become a preacher after falling for a vamp from the city.A sharecropper decides to become a preacher after falling for a vamp from the city.

- Für 1 Oscar nominiert

- 3 Gewinne & 1 Nominierung insgesamt

Matthew 'Stymie' Beard

- Child

- (Nicht genannt)

Evelyn Pope Burwell

- Singer

- (Nicht genannt)

Eddie Conners

- Singer

- (Nicht genannt)

William Allen Garrison

- Heavy

- (Nicht genannt)

Eva Jessye

- Singer

- (Nicht genannt)

Sam McDaniel

- Adam

- (Nicht genannt)

Clarence Muse

- Church Member

- (Nicht genannt)

Empfohlene Bewertungen

A film that has a lot to unpack, and a lot to consider. It was made with an all-black cast by director King Vidor with what I believe were good intentions, has some fantastic performances, and tells a good story, but it touches a nerve with its stereotypes. What was liberal in 1929 is known to be backwards today, and this is what makes it such a complicated film. I enjoyed it for its positives and would suggest viewers not dismiss the film entirely, but I'll start with acknowledging the problematic parts, at least the way I see them, FWIW.

As African-American intellectuals like Lorraine Hansberry, James Baldwin, and others explained it so well in the late 1950's, one of the mechanisms white Americans used to cope with the outrageous horror of slavery after it ended was to continue thinking of blacks as somehow different than human. An outright racist considered them lesser, inferior beings. Well-intentioned liberals often embraced the idea that they were a simple, rhythmical people, steeped in Christianity, and possessing a deep wellspring of forgiveness. This reduced the collective guilt over a horror which simply could not be faced, and which to this day has not been reconciled. The liberal view of the day, what we see manifested in this film, is of course preferable to what we might see from someone like D.W. Griffith, but either characterization is dangerous, and robs African-Americans of their humanity.

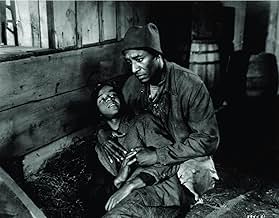

In the film, the characters are way too happy being poor and picking cotton. I mean, it's better than 'Gone with the Wind', where they're happy to be the slaves of masters who are portrayed as benevolent and genteel, but it still falls into the trap of thinking of them as just simple folk who like to dance after a long day in the field. See, they're all free and happy now, slavery is over, and we certainly don't need to think about some form of reparations for our part in 300+ years of slavery and the death of upwards of 100 million Africans. The film is trying to give its mostly white audience a window into African-American life, similar to how the 'expedition' films from the period presented Polynesians, Inuits, etc ... many of which were made with cultural condescension, and it's telling that there are no white characters, discriminating against them or terrorizing them, as if they were in their own little bubble, or on an island somewhere. And unfortunately, coming along with the singing, dancing, and revival preaching are stereotypes. One of the worst is in the way the main character (Daniel L. Haynes) simply cannot control himself around women, and one (Nina Mae McKinney) in particular. Even though we may see some of that in white individuals from other films (Lionel Barrymore as a preacher in 'Sadie Thompson' from 1928 comes to mind), here it's associated with such a negative stereotype, the sexual aggressiveness of black men, and amplified by Haynes's eyes twitching in tight shots.

On the other hand, I think we have to give the film and Vidor some credit too. To make his first sound picture with an all-black cast is impressive. The main story line could have been based on white characters, and we see a range of human emotion and folly. The musical performances and the dancing from the main characters and various others are excellent. Daniel L. Haynes has quite a presence, and his deep voice and preaching style might just convert you if you're not careful. I loved his imitating a train chugging down the tracks in one of his sermons. Nina Mae McKinney is a revelation too - so well-cast, conveying depravity, wildness, deceit, and contrition all very well. It's all the more impressive considering she was just 17 years old when the film came out, and 16 when it was filmed. The acting is a little uneven, consistent for the period, but one thing I noticed was that the performances are uniformly less reserved and restrained, and that along with pretty damn good sound quality results in more energy and vibrancy on the screen - especially as it compares to other early talkies in 1929 and 1930, many of which are incredibly creaky and brittle. I had a little bit of the same feeling I had about 'Stormy Weather' (1943), another film containing stereotypes, that the performances transcended the narrow framework they were placed in.

Because of all of the concerns about race, I think some of Vidor's great shots in the film get overlooked. He shows us the cotton ginning process, and Haynes up on a huge lumber saw cutting long boards from a tree. He gives a shot of a fantastic drummer in a ragtime band, throwing and catching his sticks as he plays. He shows us the orgiastic gyrations of a wild church scene with excellent camera work, and gives us a chase through a swamp that was likely influential to other filmmakers. Lastly, while McKinney's character falls into the age-old (and misogynistic) temptress type, we also see that she can take care of herself, in one scene beating the hell out of a guy with a fireplace poker after he tries to force himself on her, which despite the violence was frankly great to see.

The bottom line though ... was this film a step forward? That's hard for me to answer. It's worth seeing and the dialog which probes a little deeper than the extreme positions (e.g. distilling it down to "old-timey racism" or "what's the problem, there's no racism here") is worthwhile. If you want to get a better window into the African-American experience from this period, however, you should check out 'Within Our Gates' (1920) by director Oscar Micheaux.

As African-American intellectuals like Lorraine Hansberry, James Baldwin, and others explained it so well in the late 1950's, one of the mechanisms white Americans used to cope with the outrageous horror of slavery after it ended was to continue thinking of blacks as somehow different than human. An outright racist considered them lesser, inferior beings. Well-intentioned liberals often embraced the idea that they were a simple, rhythmical people, steeped in Christianity, and possessing a deep wellspring of forgiveness. This reduced the collective guilt over a horror which simply could not be faced, and which to this day has not been reconciled. The liberal view of the day, what we see manifested in this film, is of course preferable to what we might see from someone like D.W. Griffith, but either characterization is dangerous, and robs African-Americans of their humanity.

In the film, the characters are way too happy being poor and picking cotton. I mean, it's better than 'Gone with the Wind', where they're happy to be the slaves of masters who are portrayed as benevolent and genteel, but it still falls into the trap of thinking of them as just simple folk who like to dance after a long day in the field. See, they're all free and happy now, slavery is over, and we certainly don't need to think about some form of reparations for our part in 300+ years of slavery and the death of upwards of 100 million Africans. The film is trying to give its mostly white audience a window into African-American life, similar to how the 'expedition' films from the period presented Polynesians, Inuits, etc ... many of which were made with cultural condescension, and it's telling that there are no white characters, discriminating against them or terrorizing them, as if they were in their own little bubble, or on an island somewhere. And unfortunately, coming along with the singing, dancing, and revival preaching are stereotypes. One of the worst is in the way the main character (Daniel L. Haynes) simply cannot control himself around women, and one (Nina Mae McKinney) in particular. Even though we may see some of that in white individuals from other films (Lionel Barrymore as a preacher in 'Sadie Thompson' from 1928 comes to mind), here it's associated with such a negative stereotype, the sexual aggressiveness of black men, and amplified by Haynes's eyes twitching in tight shots.

On the other hand, I think we have to give the film and Vidor some credit too. To make his first sound picture with an all-black cast is impressive. The main story line could have been based on white characters, and we see a range of human emotion and folly. The musical performances and the dancing from the main characters and various others are excellent. Daniel L. Haynes has quite a presence, and his deep voice and preaching style might just convert you if you're not careful. I loved his imitating a train chugging down the tracks in one of his sermons. Nina Mae McKinney is a revelation too - so well-cast, conveying depravity, wildness, deceit, and contrition all very well. It's all the more impressive considering she was just 17 years old when the film came out, and 16 when it was filmed. The acting is a little uneven, consistent for the period, but one thing I noticed was that the performances are uniformly less reserved and restrained, and that along with pretty damn good sound quality results in more energy and vibrancy on the screen - especially as it compares to other early talkies in 1929 and 1930, many of which are incredibly creaky and brittle. I had a little bit of the same feeling I had about 'Stormy Weather' (1943), another film containing stereotypes, that the performances transcended the narrow framework they were placed in.

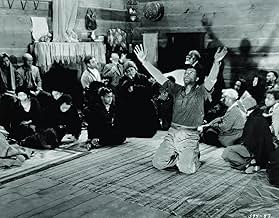

Because of all of the concerns about race, I think some of Vidor's great shots in the film get overlooked. He shows us the cotton ginning process, and Haynes up on a huge lumber saw cutting long boards from a tree. He gives a shot of a fantastic drummer in a ragtime band, throwing and catching his sticks as he plays. He shows us the orgiastic gyrations of a wild church scene with excellent camera work, and gives us a chase through a swamp that was likely influential to other filmmakers. Lastly, while McKinney's character falls into the age-old (and misogynistic) temptress type, we also see that she can take care of herself, in one scene beating the hell out of a guy with a fireplace poker after he tries to force himself on her, which despite the violence was frankly great to see.

The bottom line though ... was this film a step forward? That's hard for me to answer. It's worth seeing and the dialog which probes a little deeper than the extreme positions (e.g. distilling it down to "old-timey racism" or "what's the problem, there's no racism here") is worthwhile. If you want to get a better window into the African-American experience from this period, however, you should check out 'Within Our Gates' (1920) by director Oscar Micheaux.

"Hallelujah!" is fascinating from a film history perspective. King Vidor created the first Hollywood film with an all-black cast, and depicted in almost documentary fashion what life was like for poor blacks living in America's deep South. Alas, any interest the film held for me was purely academic -- as a film, it's otherwise rather boring.

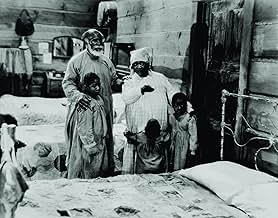

The nominal plot focuses on Zeke, who lives with his large family and helps with their cotton-picking business. We watch him struggle with the demons that plague mortal man -- like gambling and horniness -- give into them, repent, give into them again, repent, and so on, until he comes back at the end to the family who loves him. Indeed, family and religion are the two dominant pillars around which these poor folk anchor themselves, much as they are in any culture. Much of the film consists of long scenes depicting a sermon, a baptism, a local dance. There are countless scenes of characters lifting their hands to heaven, praying to Jesus to guide them. It's all rather dramatically inert, and the film is too long. If you are religious yourself, I imagine these scenes might have a certain power to them. I found all of the weeping and wailing tiresome after a while.

Credit must go to Vidor, though, for even bothering to make this film at a time when much of America didn't care all that much about the black people. The movie is a memento of the role film can play in leading cultural progress.

Grade: C+

The nominal plot focuses on Zeke, who lives with his large family and helps with their cotton-picking business. We watch him struggle with the demons that plague mortal man -- like gambling and horniness -- give into them, repent, give into them again, repent, and so on, until he comes back at the end to the family who loves him. Indeed, family and religion are the two dominant pillars around which these poor folk anchor themselves, much as they are in any culture. Much of the film consists of long scenes depicting a sermon, a baptism, a local dance. There are countless scenes of characters lifting their hands to heaven, praying to Jesus to guide them. It's all rather dramatically inert, and the film is too long. If you are religious yourself, I imagine these scenes might have a certain power to them. I found all of the weeping and wailing tiresome after a while.

Credit must go to Vidor, though, for even bothering to make this film at a time when much of America didn't care all that much about the black people. The movie is a memento of the role film can play in leading cultural progress.

Grade: C+

It's important to realize this was only the first year of sound pictures. Seen in that light, HALLELUJAH! has a remarkable fluidity, and a freedom from the tyranny of the sound camera that is little short of astonishing. (See "Singin' in the Rain" for a realistic depiction of this problem.) The acting is on a high level, if somewhat dated. King Vidor did an admirable job in depicting his characters' life condition, and was deservedly nominated as Best Director of 1929/30.

There's something hypnotic about good preaching. All that passion, all that energy, whether it's in film or in person, has a cumulative power. It's hard to doubt the spreading power of religion when you see Daniel L. Haynes (this film) or Robert Duvall ("The Apostle"), or read the sermon at the end of "The Sound and the Fury." Feverishly, they try and communicate God's word. They rant, they rave, they speak quickly and with an undeniable amount of integrity. They get the crowd going, usually in whoops and outbursts, and one man's conversation with God becomes a community event. (Indeed, the power of a worked-up crowd is a powerful tool in and of itself).

That's what's so terrific about King Vidor's "Hallelujah." Everyone's up in arms about one thing or another in this movie, whether it's money, sex, or Jesus. Early in the film there's a rather ludicrous scene where the hero's brother is accidentally killed, due to the hero's folly and hubris. That's his Sin, for which he must Redeem Himself Before God. There's also a woman who represents Temptation, who leads him astray time and time again. In the end there's an extended chase through a swamp, that would be done again in Kurosawa's "Stray Dogs."

All of that's well and good, but the film really peaks during the sermon sequences. Done wrong, sermons in movies usually pass by unnoticed, or are used as a clothsline to hang lame jokes about apathetic churchgoers. Done right, as in this film, "The Apostle," and the most unusual ones in "Beloved," they can be as captivating as if you were really in attendance. It's a testament to the power of the motion picture.

That's what's so terrific about King Vidor's "Hallelujah." Everyone's up in arms about one thing or another in this movie, whether it's money, sex, or Jesus. Early in the film there's a rather ludicrous scene where the hero's brother is accidentally killed, due to the hero's folly and hubris. That's his Sin, for which he must Redeem Himself Before God. There's also a woman who represents Temptation, who leads him astray time and time again. In the end there's an extended chase through a swamp, that would be done again in Kurosawa's "Stray Dogs."

All of that's well and good, but the film really peaks during the sermon sequences. Done wrong, sermons in movies usually pass by unnoticed, or are used as a clothsline to hang lame jokes about apathetic churchgoers. Done right, as in this film, "The Apostle," and the most unusual ones in "Beloved," they can be as captivating as if you were really in attendance. It's a testament to the power of the motion picture.

"Hallelujah" is a very interesting film. For that reason alone, it should be seen. It has an all-black cast and it was released in 1929, just as sound was first being used in films.

However, it is a very uneven production. We should give it some slack because of when it was produced, but not to mention its deficiencies would be dishonest. The acting, the lighting, the sound--all are uneven. Sometimes it is distracting, sometimes not.

Zeke (Daniel L. Haynes) is the central character. He lives with his large family, growing cotton. When the crop is harvested, he and his brother have it processed and baled. They deliver it to the riverboat and sell it on the dock. There in the city, with the money burning a hole in his pocket, he is introduced to some unscrupulous characters. He is naïve and obviously unaware of some basic rules of life and film: Never shoot with another man's dice. Never take a knife to a gunfight. And never, never go for a woman who gives her attentions to the highest bidder.

The story is filled with clichés and stereotypes, and it frequently drags. It has its compelling moments, like a chase through a swamp. But what bothers me most is the overly-dramatic acting. This is partly due to the fact that many of the scenes were couched in religious fervor. There are revival scenes, baptism scenes, scenes of general praying. In fact, the entire film is presented as a religious parable. Often when the characters speak, it is as if they are preaching. This interferes with the authenticity of the action, making some characters seem more caricatures than real people.

"Hallelujah" is a musical. Songs accent almost every scene. Most of them are gospel/spirituals. But the two best songs were written by Irving Berlin ("At The End of the Road" and "Swanee Shuffle").

However, it is a very uneven production. We should give it some slack because of when it was produced, but not to mention its deficiencies would be dishonest. The acting, the lighting, the sound--all are uneven. Sometimes it is distracting, sometimes not.

Zeke (Daniel L. Haynes) is the central character. He lives with his large family, growing cotton. When the crop is harvested, he and his brother have it processed and baled. They deliver it to the riverboat and sell it on the dock. There in the city, with the money burning a hole in his pocket, he is introduced to some unscrupulous characters. He is naïve and obviously unaware of some basic rules of life and film: Never shoot with another man's dice. Never take a knife to a gunfight. And never, never go for a woman who gives her attentions to the highest bidder.

The story is filled with clichés and stereotypes, and it frequently drags. It has its compelling moments, like a chase through a swamp. But what bothers me most is the overly-dramatic acting. This is partly due to the fact that many of the scenes were couched in religious fervor. There are revival scenes, baptism scenes, scenes of general praying. In fact, the entire film is presented as a religious parable. Often when the characters speak, it is as if they are preaching. This interferes with the authenticity of the action, making some characters seem more caricatures than real people.

"Hallelujah" is a musical. Songs accent almost every scene. Most of them are gospel/spirituals. But the two best songs were written by Irving Berlin ("At The End of the Road" and "Swanee Shuffle").

Wusstest du schon

- WissenswertesAlthough this film is frequently touted as the first black-cast film produced in Hollywood, it is actually predated by the more obscure Hearts in Dixie (1929).

- PatzerWhen Zeke confronts Chick and Hot Shot and strong-arms them in front of the crowd, the shadow of the microphone falls across Hot Shot as he is pushed to the background of the scene and tries to regain his composure. The shadow of the boom is also visible falling across the extras behind him.

- Alternative VersionenMGM also issued this movie in a silent version, with Marian Ainslee writing the titles.

- SoundtracksSometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child

(uncredited)

Traditional Spiritual

Sung offscreen during the opening credits

Top-Auswahl

Melde dich zum Bewerten an und greife auf die Watchlist für personalisierte Empfehlungen zu.

- How long is Hallelujah?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Laufzeit

- 1 Std. 49 Min.(109 min)

- Farbe

- Seitenverhältnis

- 1.20 : 1

Zu dieser Seite beitragen

Bearbeitung vorschlagen oder fehlenden Inhalt hinzufügen