IMDb-BEWERTUNG

7,6/10

5041

IHRE BEWERTUNG

Dieser Film zeigt uns einen Tag in Berlin: den Rhythmus der Zeit, vom frühen Morgen bis in die tiefe Nacht.Dieser Film zeigt uns einen Tag in Berlin: den Rhythmus der Zeit, vom frühen Morgen bis in die tiefe Nacht.Dieser Film zeigt uns einen Tag in Berlin: den Rhythmus der Zeit, vom frühen Morgen bis in die tiefe Nacht.

- Regie

- Drehbuch

- Hauptbesetzung

Paul von Hindenburg

- Self

- (Nicht genannt)

Empfohlene Bewertungen

`Berlin, Symphony of a Great City' is a film I've watched over and over with fascination. I think it's true that it is not so much about the people of Berlin, although we see many of them, but the city itself as a huge living, breathing organism. Back in the 1930s filmmaker John Grierson apparently wrote that this film `created nothing,' and that it violated the first principles of documentary by showing us nothing of importance but beautiful images. Looking at it more than 70 years after its creation, however, its documentary value seems evident to me, at least. I find it fascinating just to see what the people, clothing, uniforms, vehicles, streets, parks, restaurants, shops, theaters, nightclubs, and factories looked like in that distant time and place. It's amazing to contemplate how soon this complex, sophisticated society would be consumed in the most primitive debauchery. Do these people really look that much different from those we see on our streets every day? It makes me wonder what we're all potentially capable of.

Some slight differences do seem apparent, however. When a fight breaks out in a public place today, people usually try to ignore it, or even duck their heads and run for cover. But in a scene where two men argue violently in the street, the Berliners of the 1920s crowd in close around the combatants, and even try to separate them and arbitrate the dispute, before a policeman moves in. Whether this was typically European at that time, or just typical of its era, I really can't say, but it seems strange to me today.

Although I think the majority of this film was shot in a candid manner, and looks it, it's obvious that not quite all of it was un-staged, as a previous commentator has pointed out. For example, look at the argument scene just mentioned. Considering one of the camera angles (probably from a 2nd floor window), the argument must have been staged at the exact spot where this camera could catch it, and the crowd's reaction, from above. In addition, a second camera was in place at street level to move in close, which hardly suggests a serendipitous event.

A good musical score is vitally important to bring this film to life. It's too bad the original score has been lost. It would be fascinating to know what it was like. But I think the one written by Timothy Brock for the Kino edition is superb in that it captures its changing moods and rhythms. If, as one internet reviewer commented, it seems a bit melancholy, that may be apropos considering that this beautiful city, and a great many of its inhabitants, would be consumed in fire less than 20 years later.

Some slight differences do seem apparent, however. When a fight breaks out in a public place today, people usually try to ignore it, or even duck their heads and run for cover. But in a scene where two men argue violently in the street, the Berliners of the 1920s crowd in close around the combatants, and even try to separate them and arbitrate the dispute, before a policeman moves in. Whether this was typically European at that time, or just typical of its era, I really can't say, but it seems strange to me today.

Although I think the majority of this film was shot in a candid manner, and looks it, it's obvious that not quite all of it was un-staged, as a previous commentator has pointed out. For example, look at the argument scene just mentioned. Considering one of the camera angles (probably from a 2nd floor window), the argument must have been staged at the exact spot where this camera could catch it, and the crowd's reaction, from above. In addition, a second camera was in place at street level to move in close, which hardly suggests a serendipitous event.

A good musical score is vitally important to bring this film to life. It's too bad the original score has been lost. It would be fascinating to know what it was like. But I think the one written by Timothy Brock for the Kino edition is superb in that it captures its changing moods and rhythms. If, as one internet reviewer commented, it seems a bit melancholy, that may be apropos considering that this beautiful city, and a great many of its inhabitants, would be consumed in fire less than 20 years later.

An amazing work of the 'slice of life' films of the 20s, really the main and most admirable example along with Dziga vertov's Man With the Movie Camera, to this day, the film remains an effective portrayal of the great city that Berlin was even back when the film was made. In fact, as time goes by, it picks up even greater importance because of the historical value that it holds.

What is truly admirable is the editing and the cinematography. Perhaps even more than the things that are contained in the framework, is the framework itself which has the first impact on the viewer. The wonderful photography, and the skilled editing that is able to go from man to machine, from trains to horses, from workmen to roller-coaster rids, are always elegant and original, even in regards to Vertov's later work mentioned above. It is, in fact, stylistically a Ruttmann work. Although the work of Vertov and Ruttmann are similar, there is a difference in the sense that while The man With the Movie Camera is aware of being a film, and plays with the process of film-making, Berlin actually lets the contents of the framework play out, and never quite interferes with it.

What is truly admirable is the editing and the cinematography. Perhaps even more than the things that are contained in the framework, is the framework itself which has the first impact on the viewer. The wonderful photography, and the skilled editing that is able to go from man to machine, from trains to horses, from workmen to roller-coaster rids, are always elegant and original, even in regards to Vertov's later work mentioned above. It is, in fact, stylistically a Ruttmann work. Although the work of Vertov and Ruttmann are similar, there is a difference in the sense that while The man With the Movie Camera is aware of being a film, and plays with the process of film-making, Berlin actually lets the contents of the framework play out, and never quite interferes with it.

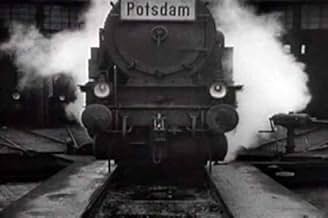

Place: Berlin. Span: one day in the life of the city circa 1927 captured by the camera. We enter by train.

One way to watch this, the most obvious I guess, is as a historic document, a snapshot of life as it was once. The old world just barely impregnated with faint traces of an archaic modernity; street cars, neon signs, busy streets, things we have now but were then just beginning to greet people. So with this mindset, as a museum piece that depicts an old version of our world.

This is fine, but I urge you to engage it differently if you can.

What if instead of merely observing exhibits from behind a glass panel, we get out from the museum into actual life? Instead of settling in for this as a historic - meaning dead, embalmed, academic - glimpse, we invigorate it with life that we know, with sunlight, texture, sound, breath that was then as real as it is now? How would it be in absolute stillness to feel present in the middle of a modern life?

This is how the film was intended after all, it's plainly revealed this way. Not a fossil for generations of curious tourists from the future, but a celebration of life 'now', modern, busy life out the window.

So no longer an old world that faintly reminds us of our own, but a new world, exciting, alluring, mysterious, alive with myriad possibilities. New things everywhere, novel pathways to travel, environments to experience. What I mean is, try to see the city as though you just got off the train and were visiting for the first time. It ends with the camera spinning around a flashing neon sign cut to match with fireworks erupting in the night sky.

I urge you to inhabit this, settle for nothing less. Let its neon flowers blossom in you.

One way to watch this, the most obvious I guess, is as a historic document, a snapshot of life as it was once. The old world just barely impregnated with faint traces of an archaic modernity; street cars, neon signs, busy streets, things we have now but were then just beginning to greet people. So with this mindset, as a museum piece that depicts an old version of our world.

This is fine, but I urge you to engage it differently if you can.

What if instead of merely observing exhibits from behind a glass panel, we get out from the museum into actual life? Instead of settling in for this as a historic - meaning dead, embalmed, academic - glimpse, we invigorate it with life that we know, with sunlight, texture, sound, breath that was then as real as it is now? How would it be in absolute stillness to feel present in the middle of a modern life?

This is how the film was intended after all, it's plainly revealed this way. Not a fossil for generations of curious tourists from the future, but a celebration of life 'now', modern, busy life out the window.

So no longer an old world that faintly reminds us of our own, but a new world, exciting, alluring, mysterious, alive with myriad possibilities. New things everywhere, novel pathways to travel, environments to experience. What I mean is, try to see the city as though you just got off the train and were visiting for the first time. It ends with the camera spinning around a flashing neon sign cut to match with fireworks erupting in the night sky.

I urge you to inhabit this, settle for nothing less. Let its neon flowers blossom in you.

This fascinating classic never loses its ability to capture the attention and stimulate the imagination of its viewers. The technique is creative and resourceful, the photography is beautiful, and the images are memorable. Everything fits together to make the idea work wonderfully well.

The opening sequence with the train is an exciting and well-conceived way to start the movie. As the pace picks up, the rush of images creates an abstract but very realistic sensation, and this train 'ride' is so enjoyable that you almost don't want it to stop.

But it's when the train reaches the station that the main part of the movie begins, presenting a very interesting stylized portrait of a typical day in Berlin, through a carefully-chosen variety of scenes and sights. It's interesting to see how the train imagery keeps coming back from time to time, and this, along with the obvious passage of time as the day progresses, gives it a coherence that makes it much more than just a collage of interesting images and scenes.

There are many interesting individual sequences, but what makes it such a gem is the way that everything fits together. The overall effect is remarkable, and it really has to be seen to be appreciated.

The opening sequence with the train is an exciting and well-conceived way to start the movie. As the pace picks up, the rush of images creates an abstract but very realistic sensation, and this train 'ride' is so enjoyable that you almost don't want it to stop.

But it's when the train reaches the station that the main part of the movie begins, presenting a very interesting stylized portrait of a typical day in Berlin, through a carefully-chosen variety of scenes and sights. It's interesting to see how the train imagery keeps coming back from time to time, and this, along with the obvious passage of time as the day progresses, gives it a coherence that makes it much more than just a collage of interesting images and scenes.

There are many interesting individual sequences, but what makes it such a gem is the way that everything fits together. The overall effect is remarkable, and it really has to be seen to be appreciated.

10J. Steed

Classic and splendid film that is still fascinating to watch. Walter Ruttmann did not make a documentary about Berlin, although 75 after date it certainly can be considered a document about a Berlin that is no more, he composed a film that tries to catch the essence of the atmosphere of a big city. The film is a good example of the art style Neue Sachlichkeit (functionalism): it is a cross-section of Berlin's life in which every element is equally important, shown without comment and in its totality it is the expression of the joy of Berlin's life. It is not a film about the life of Berliners, it is Berlin seen as a living mechanism.

The subtitle referring to Großstadt (big city) is the key, it could have been any other city. The idea as such is not the makers' prerogative. Elsewhere the fascination with the hustle and bustle of the big city was also present as was the idea to catch this on this film and in music: e.g. Cavalcanti in France made a film about Paris and the US Ferde Grofé composed his musical suite Metropolis (1927) with New York in his mind. The irony of all these endeavours is that the film or music is abstract, but that the result is a romanticizing view.

Ruttmann made several abstract film and he refers to them in the beginning with abstract horizontal lines dissolving to rail way tracks. In my view the rest of the film is also abstract. Although we see real people and situations the brilliant editing constantly keeps the film abstract: the situation and the people in a shot are not important, important is the juxtaposition to other shots: is the composition varied enough?. Thus we see a filmic composition (in stead of a musical one) and the subtitle Symphony is just. As with every composition the theme has to be modulated to keep it interesting and it is here where the weakness of the film is. The building up from the start and elaboration up to the beginning of the afternoon is splendid, precise and exiting; but from that point it bogs down for a while: we see another shop, another street etc. without adding much to what already was. It may be that Ruttmann was aware of this, note how quickly he finishes the afternoon to continue with the night-life and then immediately all the excitement and filmic fun is back.

In an 1939 interview cameraman Karl Freund said that everything possible was filmed using only candid cameras. I have my doubts. Let's take for example the sequence of the drowning lady: how could he make an extreme close-up with a hidden camera in such a brilliant angle? (By the way: if she really tried to commit suicide, was Freund himself not only one of the gaping bystanders without doing anything to save her?) How could he foresee the right angle to film the prostitute picking up her client near the cornered shop window? Not that it matters for the quality of the film, but it proofs the old adagium: filming is deceiving.

The subtitle referring to Großstadt (big city) is the key, it could have been any other city. The idea as such is not the makers' prerogative. Elsewhere the fascination with the hustle and bustle of the big city was also present as was the idea to catch this on this film and in music: e.g. Cavalcanti in France made a film about Paris and the US Ferde Grofé composed his musical suite Metropolis (1927) with New York in his mind. The irony of all these endeavours is that the film or music is abstract, but that the result is a romanticizing view.

Ruttmann made several abstract film and he refers to them in the beginning with abstract horizontal lines dissolving to rail way tracks. In my view the rest of the film is also abstract. Although we see real people and situations the brilliant editing constantly keeps the film abstract: the situation and the people in a shot are not important, important is the juxtaposition to other shots: is the composition varied enough?. Thus we see a filmic composition (in stead of a musical one) and the subtitle Symphony is just. As with every composition the theme has to be modulated to keep it interesting and it is here where the weakness of the film is. The building up from the start and elaboration up to the beginning of the afternoon is splendid, precise and exiting; but from that point it bogs down for a while: we see another shop, another street etc. without adding much to what already was. It may be that Ruttmann was aware of this, note how quickly he finishes the afternoon to continue with the night-life and then immediately all the excitement and filmic fun is back.

In an 1939 interview cameraman Karl Freund said that everything possible was filmed using only candid cameras. I have my doubts. Let's take for example the sequence of the drowning lady: how could he make an extreme close-up with a hidden camera in such a brilliant angle? (By the way: if she really tried to commit suicide, was Freund himself not only one of the gaping bystanders without doing anything to save her?) How could he foresee the right angle to film the prostitute picking up her client near the cornered shop window? Not that it matters for the quality of the film, but it proofs the old adagium: filming is deceiving.

Wusstest du schon

- WissenswertesThe shooting was done over 18 months though the resulting feature gives the impression of just one day in the city.

- VerbindungenFeatured in Lulu in Berlin (1984)

Top-Auswahl

Melde dich zum Bewerten an und greife auf die Watchlist für personalisierte Empfehlungen zu.

- How long is Berlin: Symphony of Metropolis?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Erscheinungsdatum

- Herkunftsland

- Sprache

- Auch bekannt als

- Berlin: Symphony of a Metropolis

- Drehorte

- Berlin Cathedral, Mitte, Berlin, Deutschland(aka Berliner Dom)

- Produktionsfirmen

- Weitere beteiligte Unternehmen bei IMDbPro anzeigen

- Laufzeit

- 1 Std. 5 Min.(65 min)

- Farbe

- Sound-Mix

- Seitenverhältnis

- 1.33 : 1

Zu dieser Seite beitragen

Bearbeitung vorschlagen oder fehlenden Inhalt hinzufügen