IMDb-BEWERTUNG

8,0/10

16.101

IHRE BEWERTUNG

Ein alternder Hotelportier sieht sich nach dem Verlust seines prestigeträchtigen Jobs in einem luxuriösen Hotel dem Hohn seiner Freunde, Nachbarn und der Gesellschaft ausgesetzt.Ein alternder Hotelportier sieht sich nach dem Verlust seines prestigeträchtigen Jobs in einem luxuriösen Hotel dem Hohn seiner Freunde, Nachbarn und der Gesellschaft ausgesetzt.Ein alternder Hotelportier sieht sich nach dem Verlust seines prestigeträchtigen Jobs in einem luxuriösen Hotel dem Hohn seiner Freunde, Nachbarn und der Gesellschaft ausgesetzt.

- Auszeichnungen

- 2 wins total

O.E. Hasse

- Small Role

- (Nicht genannt)

Harald Madsen

- Wedding Musician

- (Nicht genannt)

Neumann-Schüler

- Small Role

- (Nicht genannt)

Carl Schenstrøm

- Wedding Musician

- (Nicht genannt)

Erich Schönfelder

- Small role

- (Nicht genannt)

Empfohlene Bewertungen

Warning - Possible spoilers lie within.

This is the first silent movie I have watched in its entirety, having previously found myself becoming restless and distracted, I normally find them quite difficult to watch. I came across the Criterion edition of the movie in a large collection of Laserdiscs that I purchased recently, and decided to give it a try. I was speechless.

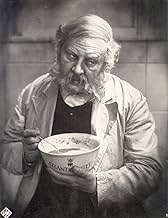

'The Last Laugh' (or 'The Last Man', as its translation would lead you to believe, is a touching story from director F.W. Murnau about an un-named Hotel Porter & Doorman (played excellently by Emil Jannings) who, through no fault of his own, is demoted to Lavatory attendant, and we hereby watch as his life collapses around him. It's an incredibly emotional story - during his downfall, as his friends and family mock him, Jannings' depressed, hunched-over figure can be painfully sad to watch. I found myself filling up in the scene when he finally hands his beloved porter's uniform over to the night watchman.

A landmark in the era of silent films, Murnau used some very clever camera tricks (such as smearing vaseline on the camera lens for 'dream' sequences). It was also one of the first films to use a completely free moving camera with no tripod, testimony to the success of this can be seen immediately in the first scene as the film starts. There are also no title cards in the film. Nor are they needed - The story is carried perfectly by the actors and on no occasion do you feel that you don't know what is going on.

I won't give anything away here, but there are some people that may feel the ending is a little out of place - However, I had grown so fond on Jannings' character that in a way, I was relieved to see the film move on from the final scene where he is sat hunched on the seat in the washroom - and for him to finally have 'The Last Laugh' so to speak :o)

If you have any interest in old cinema, and have not seen this, or just fancy a change from all of the samey Hollywood flicks being churned out right now, I suggest you hunt out a copy right away. Highly recommended.

This is the first silent movie I have watched in its entirety, having previously found myself becoming restless and distracted, I normally find them quite difficult to watch. I came across the Criterion edition of the movie in a large collection of Laserdiscs that I purchased recently, and decided to give it a try. I was speechless.

'The Last Laugh' (or 'The Last Man', as its translation would lead you to believe, is a touching story from director F.W. Murnau about an un-named Hotel Porter & Doorman (played excellently by Emil Jannings) who, through no fault of his own, is demoted to Lavatory attendant, and we hereby watch as his life collapses around him. It's an incredibly emotional story - during his downfall, as his friends and family mock him, Jannings' depressed, hunched-over figure can be painfully sad to watch. I found myself filling up in the scene when he finally hands his beloved porter's uniform over to the night watchman.

A landmark in the era of silent films, Murnau used some very clever camera tricks (such as smearing vaseline on the camera lens for 'dream' sequences). It was also one of the first films to use a completely free moving camera with no tripod, testimony to the success of this can be seen immediately in the first scene as the film starts. There are also no title cards in the film. Nor are they needed - The story is carried perfectly by the actors and on no occasion do you feel that you don't know what is going on.

I won't give anything away here, but there are some people that may feel the ending is a little out of place - However, I had grown so fond on Jannings' character that in a way, I was relieved to see the film move on from the final scene where he is sat hunched on the seat in the washroom - and for him to finally have 'The Last Laugh' so to speak :o)

If you have any interest in old cinema, and have not seen this, or just fancy a change from all of the samey Hollywood flicks being churned out right now, I suggest you hunt out a copy right away. Highly recommended.

10thao

The camera work and the sets in this film where so breathtaking and powerful that they changed the film language forever. It is in many ways the Citizen Kane of its time.

It was so revolutionary that Hollywood (Fox) tried desperately to get Murnau to work for them and teach them how to do all these things (which he did some years later). The main revolutionary thing was the fluidity of the camera (or the unchanged camera, as it was called). There was no steady cam at this time, but still they managed to strap the camera to the body of the cameraman without getting a shaky pictures.

The set is just amazing. It is difficult to believe that this is not a real city. All the special effects help also to make this believable (special effects that are still today astonishing and believable).

The makeup is also great. Emil Jannings was only 40 years old when he made this film but he really looks like an old man (and acts like one too).

But the greatest thing about this film is how much Murnau manages to say with out the help of inter titles. This is visual storytelling at it's best.

Murnau had come a long way from Nosferatu but he still had a long way to go and a lot to teach us before his untimely death. The Last Laugh is not only one of his best films, it is also most likely his most important one, and one of the most important films in film history.

It was so revolutionary that Hollywood (Fox) tried desperately to get Murnau to work for them and teach them how to do all these things (which he did some years later). The main revolutionary thing was the fluidity of the camera (or the unchanged camera, as it was called). There was no steady cam at this time, but still they managed to strap the camera to the body of the cameraman without getting a shaky pictures.

The set is just amazing. It is difficult to believe that this is not a real city. All the special effects help also to make this believable (special effects that are still today astonishing and believable).

The makeup is also great. Emil Jannings was only 40 years old when he made this film but he really looks like an old man (and acts like one too).

But the greatest thing about this film is how much Murnau manages to say with out the help of inter titles. This is visual storytelling at it's best.

Murnau had come a long way from Nosferatu but he still had a long way to go and a lot to teach us before his untimely death. The Last Laugh is not only one of his best films, it is also most likely his most important one, and one of the most important films in film history.

People seem compelled to speak in superlative-terms when talking about the great directors; which film is their greatest, which ones are underrated, etc. But this is a film so simple in its themes, so modest in its methods, that it doesn't lend itself to these labels very easily.

"Nosferatu" was revolutionary, but based on intensity, something that doesn't age very well. Other directors took up this notion of visual intensity (Leni, Boese) but structuralized it, and created the real German Horror masterpieces ("Waxworks," "Golem"). Murnau's discovery came later, with this film. That film narrative wasn't something that you followed linearly, but something you become immersed in. The lack of title-cards is not a gimmick, but a conscious decision not to interrupt the flow of this immersion. Reading is rational (hearing, slightly less so) and prevents this from taking place.

Add a Gogolian tale of aging and dignity, and Murnau makes magic. This is what "touching" and "moving" films should be like.

4 out of 5 - An excellent film

"Nosferatu" was revolutionary, but based on intensity, something that doesn't age very well. Other directors took up this notion of visual intensity (Leni, Boese) but structuralized it, and created the real German Horror masterpieces ("Waxworks," "Golem"). Murnau's discovery came later, with this film. That film narrative wasn't something that you followed linearly, but something you become immersed in. The lack of title-cards is not a gimmick, but a conscious decision not to interrupt the flow of this immersion. Reading is rational (hearing, slightly less so) and prevents this from taking place.

Add a Gogolian tale of aging and dignity, and Murnau makes magic. This is what "touching" and "moving" films should be like.

4 out of 5 - An excellent film

Although the Golden Twenties of German cinema, a golden age corresponding approximately to the era from the making of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari in 1919 to Hitler's absorption of the German film industry for the purposes of the Nazi regime, has come to be widely associated in public consciousness with the grotesque, the mystical and the fantastic of German Expressionism, indeed with such iconic figures to spearhead it as Nosferatu, the Somnabulist, Dr. Caligari, Mephisto and the Golem, all of them having their roots in the folklore or a fantastic reimagined past, there was also a more realistic, if no less tragic, depiction of a middle-class present with a focus on a psychological, as opposed to metaphysical, aspect.

By 1924 the acceptance of the Dawes Plan by Germany had lulled the German Republic into a sense of economic stability that was to last until the stock market crash in 1929. It was that same stability that most hurt the German film industry, as the Dawes Plan imposed the reduction of all exports, leaving many independent production companies without foreign markets for their product. In the years to come Hollywood would seize this unique financial opportunity to break down its only European rival, but before major box-office flops like Fritz Lang's epic rendition of Die Nibelungen (1924) and Metropolis (1927) and FW Murnau's Faust (1926) would bring UFA to its proverbial knees in debt to German banks, little films like The Last Laugh (1924) and Varieté (1925) were the toast of the town in both sides of the Atlantic.

Emil Jannings plays an aging hotel porter who takes great pride and pleasure in his job and especially the lavish uniform that comes with it. In the miserable middle-class neighborhood he lives, being able to wake up in the morning and go to work dressed like in such a prestigious uniform is like being a general. That is until a younger man is hired in his place and he's demoted to the, undignified in his mind, job of lavatory attendant. Not bearing to lose face back home with gossiping neighbors and relatives, the old porter steals back his uniform and returns home as if nothing happened, the uniform a symbol not only of his social status but also of purpose in life.

What is most striking about The Last Laugh is the way Murnau externalizes the psychological in a grand, theatric way that could only work on stage and in silent cinema. Watch for example the look of pure anguish and horror in Janning's face when he's asked to turn in his uniform, stripping it off like he's being skinned alive. Recoiling without it into a state of defeat and abandonment like a man stripped of his own identity, with nothing to live for.

Obsessed with artistic control and exercising complete authority over the minutest details of lighting and décor, German directors pushed for an increasingly studio-bound cinema to the point that UFA in the years between 1919 and 1927 became the best equipped movie studio in the western world. The Last Laugh is no exception. The facades of apartment blocks in the background with light slanting over them, the low-class neighborhood, the busy street in front of the hotel, all of them replicated in great detail within studio limits. It's within this geography that Murnau transposes Jannings' internal world. As is proper for the inward journey of the self the protagonist faces, the aging porter starts at the busy front of the hotel only to find himself exiled in the dark bowels of the basement where he remains hidden, that is until the film's tacked-on happy ending.

The only false note in an otherwise perfect film is the happy ending Murnau and scriptwriter Carl Mayer (of Caligari fame) were forced to devise by UFA executives anxious for the box office success of their movie. It's not that it doesn't work because such a tragic tale precludes a happy ending, after all one of the most memorable endings in all cinema is that of Capra's It's a Wonderful Life and it doesn't get any more saccharine than that, but because it happens in such a tacked-on deus-ex-machina fashion that it feels like a complete cop-out. It's lame now and it was lame then and Murnau no doubt understood that as he flashes a title card (the only title card in the film) more or less apologizing that "that's how the movie would've ended if I didn't have a boss to keep happy so here's a they-lived-happily-ever-after epilogue, take it with a pinch of salt or ignore it altogether". It's noteworthy however that it's not pure schmaltzy tripe. It feels as though Murnau is taking a perverse, vulgar pleasure in delivering what was asked of him.

Exceptionally photographed, with a modern feel to Murnau's camera-work that places it well ahead of its time compared to other silents, a great example of purely visual storytelling without the cumbersome crutches of the title cards, The Last Laugh stands not only as a triumph of Weimar cinema but as masterpiece almost 100 years later.

By 1924 the acceptance of the Dawes Plan by Germany had lulled the German Republic into a sense of economic stability that was to last until the stock market crash in 1929. It was that same stability that most hurt the German film industry, as the Dawes Plan imposed the reduction of all exports, leaving many independent production companies without foreign markets for their product. In the years to come Hollywood would seize this unique financial opportunity to break down its only European rival, but before major box-office flops like Fritz Lang's epic rendition of Die Nibelungen (1924) and Metropolis (1927) and FW Murnau's Faust (1926) would bring UFA to its proverbial knees in debt to German banks, little films like The Last Laugh (1924) and Varieté (1925) were the toast of the town in both sides of the Atlantic.

Emil Jannings plays an aging hotel porter who takes great pride and pleasure in his job and especially the lavish uniform that comes with it. In the miserable middle-class neighborhood he lives, being able to wake up in the morning and go to work dressed like in such a prestigious uniform is like being a general. That is until a younger man is hired in his place and he's demoted to the, undignified in his mind, job of lavatory attendant. Not bearing to lose face back home with gossiping neighbors and relatives, the old porter steals back his uniform and returns home as if nothing happened, the uniform a symbol not only of his social status but also of purpose in life.

What is most striking about The Last Laugh is the way Murnau externalizes the psychological in a grand, theatric way that could only work on stage and in silent cinema. Watch for example the look of pure anguish and horror in Janning's face when he's asked to turn in his uniform, stripping it off like he's being skinned alive. Recoiling without it into a state of defeat and abandonment like a man stripped of his own identity, with nothing to live for.

Obsessed with artistic control and exercising complete authority over the minutest details of lighting and décor, German directors pushed for an increasingly studio-bound cinema to the point that UFA in the years between 1919 and 1927 became the best equipped movie studio in the western world. The Last Laugh is no exception. The facades of apartment blocks in the background with light slanting over them, the low-class neighborhood, the busy street in front of the hotel, all of them replicated in great detail within studio limits. It's within this geography that Murnau transposes Jannings' internal world. As is proper for the inward journey of the self the protagonist faces, the aging porter starts at the busy front of the hotel only to find himself exiled in the dark bowels of the basement where he remains hidden, that is until the film's tacked-on happy ending.

The only false note in an otherwise perfect film is the happy ending Murnau and scriptwriter Carl Mayer (of Caligari fame) were forced to devise by UFA executives anxious for the box office success of their movie. It's not that it doesn't work because such a tragic tale precludes a happy ending, after all one of the most memorable endings in all cinema is that of Capra's It's a Wonderful Life and it doesn't get any more saccharine than that, but because it happens in such a tacked-on deus-ex-machina fashion that it feels like a complete cop-out. It's lame now and it was lame then and Murnau no doubt understood that as he flashes a title card (the only title card in the film) more or less apologizing that "that's how the movie would've ended if I didn't have a boss to keep happy so here's a they-lived-happily-ever-after epilogue, take it with a pinch of salt or ignore it altogether". It's noteworthy however that it's not pure schmaltzy tripe. It feels as though Murnau is taking a perverse, vulgar pleasure in delivering what was asked of him.

Exceptionally photographed, with a modern feel to Murnau's camera-work that places it well ahead of its time compared to other silents, a great example of purely visual storytelling without the cumbersome crutches of the title cards, The Last Laugh stands not only as a triumph of Weimar cinema but as masterpiece almost 100 years later.

Der Letzte Mann is nothing short of the epitome of viewing pleasure. Beautifully shot, the urban landscape in which a noble doorman earns his keep (and humanity) is throughout dream-like, infused with a decidedly ethereal quality. Added to a magical visual backdrop is a haunting musical score, highlighted by sweeping cello chords which cut straight to the heart. With regard to prominent themes, the picture speaks volumes about the fragility of human existence and, specifically, human dignity. The shallow and arbitrary nature of a society bent predominantly on the acquisition and elevation of pecuniary wealth, as well as the perseverance of the individual through it all, is illustrated masterfully through both the zenith and nadir of the doorman's existence, as documented in this truly excellent work of the interwar period.

Wusstest du schon

- WissenswertesThe first "dolly" (a device that allows a camera to move during a shot) was created for this film. According to Edgar G. Ulmer, who worked on the film, the idea to make the first dolly came from the desire to focus on Emil Jannings' face during the first shot of the movie, as he moved through the hotel. They obviously didn't know how to make a dolly technically, so they created the first one out of a baby's carriage. They then pulled the carriage on a sort of railway that was built in the studio.

- PatzerWhen the porter comes home with the stolen coat, the third button down (which fell off earlier) is still there until a close-up of him at the door.

- Alternative VersionenThere is an Italian edition of this film on DVD, re-edited in double version (1.33:1 and 1.78:1) with the contribution of film historian Riccardo Cusin. This version is also available for streaming on some platforms.

- VerbindungenEdited into Deutschland Neu(n) Null (1991)

Top-Auswahl

Melde dich zum Bewerten an und greife auf die Watchlist für personalisierte Empfehlungen zu.

- How long is The Last Laugh?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box Office

- Bruttoertrag in den USA und Kanada

- 94.812 $

- Laufzeit

- 1 Std. 41 Min.(101 min)

- Farbe

- Sound-Mix

- Seitenverhältnis

- 1.33 : 1

Zu dieser Seite beitragen

Bearbeitung vorschlagen oder fehlenden Inhalt hinzufügen