Guests

- Juma XipaiaIndigenous activist from the Xipaya people of the Amazon.

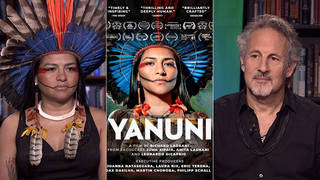

- Richard Ladkanifilmmaker.

The documentary Yanuni profiles Indigenous chief and activist Juma Xipaia, who has survived six assassination attempts while defending her people’s land from illegal gold miners and deforestation. Shortlisted for a 2026 Academy Award, the film highlights her fight for Indigenous sovereignty and the preservation of the Amazon, her historic appointment as Brazil’s first secretary of Indigenous rights and the challenges faced during the administration of former President Jair Bolsonaro.

Democracy Now! recently spoke with Juma Xipaia, as well as director Richard Ladkani.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

We look now at a new documentary about the Indigenous activist and land defender Juma Xipaia in Brazil. She’s leader of the Xipaya people and the first woman to serve as chief of Brazil’s Middle Xingu region. Over the years, she has survived six assassination attempts while confronting illegal gold miners, land grabbers and multinational corporations threatening her ancestral land. The film Yanuni has been shortlisted for an Oscar for best documentary. This is the trailer.

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] She is not just a forest. She is our mother and the cure.

REPORTER 1: Indigenous people dying at alarming rates.

REPORTER 2: Victims of the onslaught of illegal mining.

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] We’ve been at war for a very long time.

This is an emergency situation. And that responsibility is yours. It is yours!

You have no idea what it’s like to lose a child, to have your house invaded, to be expelled from your own land. You have no idea!

REPORTER 3: The creation of the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples marks a pivotal moment in the fight for Indigenous rights.

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] What’s it like to be a minister?

Are we being foolish to be optimistic?

HUGO LOSS: [translated] Just two days, and I’m going for another meeting.

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] I’m also going to another meeting.

Oh my God in heaven! I forgot to pick up Tuppak.

They are watching us. You can’t trust anyone. I’m worried. They are so violent.

HUGO LOSS: [translated] It will be fine.

We identified that this is an illegal mining base. So we will destroy it.

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] Don’t let our people be separated.

UNIDENTIFIED: [translated] Juma, get back!

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] Alcebias, can you hear me? It’s Juma.

Are you listening to me?

AMY GOODMAN: That’s the trailer for Yanuni. And this is another clip, featuring our guest, the Indigenous leader Juma Xipaia.

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] They’re invading, stealing our territories. The rivers, they’re drying up, turning into pathways of rock and mud. We’ve been at war for a very long time.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Juma Xipaia speaking in the new film Yanuni, which has been shortlisted for an Academy Award. Juma joins us now in our New York studio. And we’re joined by the film’s director, Richard Ladkani. His other films include Jane’s Journey, about Jane Goodall, who we have interviewed many times, and you can go to democracynow.org to see those interviews.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! It’s such an honor to have you with us, Juma. If you can start off by talking about what is at stake in the Amazon, why you have decided to dedicate your life to saving the Amazon and the lands of your people?

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] I am from the Xipaya people. And in my childhood, I used to listen to — that my people didn’t exist, that they were extinct already. But they did exist. All my people existed. And we were in our territory, so we needed to fight to demarcate our territory. And there were a lot of invaders and loggers and fishers saying that that was their land. And I kept listening that my people didn’t exist. And how we don’t exist? We’re here. Our memories are here. Our ancestors are here. So we understood that it was a fight not only to defend the forest and demarcate the territory. It was a fight for our existence. And I learned that. And I usually say, since I was in my mom’s womb, this fight, not only in the Amazon, but in entire Brazil and world, was since the invasion of Brazil.

So, what’s at stake right now, it’s not only our territories and the minerals and the natural resources, but mainly our existence. So, for many centuries, it wasn’t just denied, our existence as Xipaya, but many other peoples, because you used to have clean water, clean food, and we were defending that. And when you see big projects from invaders, from small invaders, but great projects that see us as a problem because we are defending the forest, we defend with our own lives every day, because we believe in the importance that it has, not only as food source and clean water, but also all the beings that have the right to exist there.

So, I learned that since I was a child, because it was what my grandmother used to do. It was what her mother used to do, and her grandmother used to do, so all these generations before me. I only exist as a woman, Indigenous woman, a Xipaya, and the territory Xipaya, because my ancestors fight for that and kept our knowledge alive so I could be living today, so I could live today. So I learned from the very beginning it was an option to defend, not only for me, so I would do exactly what my ancestors did for the next generations, which is to keep our forests standing and our people and our science and our culture and spirituality along with it in our territory.

AMY GOODMAN: Richard Ladkani, you have directed this film. What made you decide to focus on Juma? Talk about the years that you have spent on this.

RICHARD LADKANI: Well, when I started this film, I was really looking for, like, a voice of the Amazon. I was looking for someone who could represent it and touch us emotionally. And I went through a long list of people who was given to me by researchers and journalists. And Juma came up last, actually.

And the reason it was hard also to get to her is because Juma had just survived her sixth attempt on her life and was in hiding, and she didn’t want to talk to anyone. She was basically done with the world and has retreated into the forest.

This journalist friend of ours convinced her to meet me and to have a talk. And as soon as I met her for the very first time, I realized that this is going to be the voice, because she has an amazing way of speaking from the heart and reflecting upon what is actually happening in the Amazon. And I cried on that very first call, because it was so moving, what had happened to her and 15, 20 years of crisis in her life and so many terrible things. But I felt that she can touch — if she can touch me like that, she will touch the world. And that’s how I decided, in the moment, that, you know, this would be the voice.

But it was hard, because she was living a life, you know, in crisis. She was threatened. And I needed to convince her, as well, that this is a good idea, you know, to put herself out there and speak to the world through a film. So I wanted to give her as much power and security as possible by also offering a producer credit and really asking her to lead the way and just kind of take me on this journey, please, so I can document your life for the world. And I knew it was going to be a journey of trust.

AMY GOODMAN: This is astounding. Six assassination attempts against you. Talk about when these assassination attempts started, how old you were, and who is trying to kill you.

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] This is a very sensitive part. We didn’t show that in the Yanuni movie, because one of the things that Richard said to me when he proposed to me this project, when I was at a four years of silenced retreat, forced retreat — I was trying to study. Just I was trying to study medicine, and I used to live in front of the university. And just crossing the street was a big risk for me. So, when Richard came to my life, I was in forced silence retreat, too, so I could stay alive. So, of course, I didn’t want to talk with Richard or anything or anyone. It was just a matter of security and angry and frustration.

All of this because I’m never going to accept corruption into leadership. I’m never going to accept people negotiating with other corporations to negotiate our rights. It doesn’t matter if it’s a big or a small project, because this is spread all over Brazil. Especially in the Amazon, it’s no different. So, when you’re young and a woman and a mother and a leader and be a cacica, this bothers a lot of people, not only the people that are trying to implement big projects in the Amazon that don’t respect our Constitution, that guarantees the free prior consultation to Indigenous people, but also causes a lot of impact for us to communicate clarity and to visualize this process of destruction and be able to denounce that. So it’s obvious that people will see me and other people that do what I do as something dangerous, as somebody dangerous.

And all this is the way they will find to silence us, because this is what they did with other leadership in the Amazon and in Brazil. They try to silence, offering money, offering titles and work and the government, a lot of harassment and violence, attempts to silence people and also attempts to kill. So, there’s no way specifically who is trying to kill, if it’s a political and if it’s a corporation, because from where I come from, from the level of Brazil and Indigenous, the situation is very violent against Indigenous women and youth, and in the Amazon it’s no different.

The world talks about the Amazon, like we had the COP30 in Belém just now. And today I have a vision of the Amazon. And people really want to talk about the Amazon. People want to talk about the Amazon. But only the Amazon, most people look at it as a commodity, as profit, and not looking at territory rich in — rich in people, not only natural resources, rich in wisdom. And what we do in this territory is go a lane that’s keeping the forest standing. We are holding — we are holding the world. We’re sustaining the world standing, so your life and my life.

So, when you do that, you’re fighting against a lot of corporations and financial interests. So there’s no way to say, “Oh, give me a name who’s trying to kill.” There’s a lot of names. There are a lot of people that don’t want me to be here talking about this right now. So, my presence here, Indigenous people defending the territory and our lives, this bothers a lot of people. People, they don’t want me to just be silenced, but they want to silence all Indigenous people.

AMY GOODMAN: Richard, set up this clip for us that we’re about to play from the film, with the man on the ground, the protesters, and his being shot.

RICHARD LADKANI: Well, during the times of Bolsonaro, when we started filming, there were these violent protests where the Indigenous people come to the capital Brasília to —

AMY GOODMAN: And let’s just be very clear that Jair Bolsonaro is now in prison, the former president of Brazil.

RICHARD LADKANI: Exactly, yeah. No, absolutely. And during his reign of power, so to say, he was treating Indigenous people without respect, you know, calling them names and everything. And he was asking invaders to go in and grab what is theirs, you know, and no matter what the cost or the violence or whatever. And that was the reasons the Indigenous people went to Brasília to protest. And they were very often violently kind of, you know, kicked back, but with tear gas, with rubber bullets, sometimes shot at. You know, it was a very violent time. And that’s exactly the time when we started filming.

And what I couldn’t believe was the role Juma played in this fight, because she was a real leader. And when people were falling, being hurt, injured, and even, you know, killed, she would stay, and she would not budge. And she would — like, no one is left behind. You could feel that. And she was the last one there. When everyone ran, she was there protecting this one man from tear gas. It was remarkable.

AMY GOODMAN: And this is what we see in this clip from the film, Yanuni.

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] Stop! Ask them to stop. We have people on the ground. Stop, please! Why? Why are you doing this?

AMY GOODMAN: Juma. So, that’s a clip from Yanuni, but it’s not just a clip from a film, Juma. This is a part of your life. Describe who this man is on the ground — did he die? — and also your decision to stay with him, even as the Brazilian Bolsonaro troops opened fire.

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] It was one of the hardest moments of my life. It took me a moment to watch this scene, this entire scene that you just watched, because it brought a lot of memory that we’ve been facing for a long time during the Bolsonaro government, especially during that time we were protesting. This genocide government never — we never stopped resisting. We never accepted silence. We kept going to Brasília. We also occupied Brasília, which was also our territory. So, we were doing vigilance and camping around there, so we could alternate and rotate people that are awake and sleeping, because at any time, anyone could come armed and start, you know, attacking us inside the camp. So it was a constant vigilance.

And this specific day, we felt — that before the attack started, we felt something, because we were surrounded by armed people and also with horses, riding horses. They closed all the exits from where we had arrived. And we realized that they had shields, and they were, like, closing, enclosing us in this space, so we knew something was going to happen. So, a few days before, there was no protection barrier there. We could go back and forth. And this day specifically, they put a barrier that we couldn’t go across, and we couldn’t even reach the shade, because the sun was also very intense. So we felt spiritually that something was coming.

And it didn’t take too long for the — they start shooting. So, Alcebias is the guy on the ground. I didn’t know him at that moment. I didn’t know who he was. I knew that he was a relative, an Indigenous person, so I ran. How we could help him? Because most people were worried about women and children, because there were a lot of women and children there. And when we saw the shootings, let’s take — let’s get him out of there, because he got a lot of rubber shots, and something reached his lungs, too, so he couldn’t breathe, and that’s why he passed out. So, our biggest concern was to not let him die there, that we would be able to get support for him and move him there. And every time the first responders tried to get there, the police didn’t stop shooting, so they couldn’t reach us.

When we get to the movie, that portion of the movie, and we are under there, and they still do the tear gas, that was — the gas couldn’t — it was under — we were covered, so the gas couldn’t really dissipate. So I couldn’t think straight at that moment. But one thing that I knew, we knew that all these protests, we know that we go, but we don’t know if we’re going to come back. But I knew why we were there, and I was willing to do what needed to be done to either stay with him there or even get shot there or even die there. But I was happy, and it’s a just cause. It’s a just fight. It’s a search for justice. If I am to be afraid, I won’t leave my house, because threats are constant. But that was a moment of decision that I chose to be with him.

Did Alcebias — did he survive? And after that, we got support for him. The first responders came. For the fifth time when they tried to reach them, they were able to. I don’t remember very much, because after that, I passed out. And then, when I woke up, I was on the other side, because I was carried out that way. And the next time I got news from him was at 2:00 in the morning when I got a phone from the person that was with him. And then I went there and knew he was breathing through machine, and he was conscious, but he was still feeling all the shots, and he was still alive. So, it was just in this moment that I could cry, that I started crying after all that happened. So I had the relief sensation: “OK, great, he’s alive, so we made it.”

And that was when I found out that he was Alcebias from the Pará, from Roraima, and he was the coordinator of the youth people there. And in that moment, I didn’t even know even who he was. I just knew he was an Indigenous, a relative. And that’s where I got this headdress, which is a sacred headdress. And then I was to Roraima, where they hosted me, and with a lot of respect. And it’s a territory, a very strong territory, an organization very strong there, a governance very strong. I have the best examples and models of leadership are there. And it was a big surprise for me that he was the coordinator of the youth there. And he was trying to strengthen his work there and his resistance there, and all the violence, that together we could do this, because one of the things that we are taught, never leave anyone behind.

AMY GOODMAN: You mention your headdress, Juma. And I was wondering if you can describe it for our radio and television audience. Where are the feathers from? And how, in the film, the whole audience becomes centered, because you do this ceremony at the beginning, each time you come out on a stage.

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] It’s a symbol of strength and resistance. So, when I put the headdress down, when I do this, it’s to bring all the forest, all the strength of the people, not only my people, but all peoples, especially the — from Roraima, where this headdress comes.

And who made this for me was a big leadership youth in [inaudible]. And he dreamed about this, this headdress, and then he gifted this to me when I went there. I had one that was smaller — I think you saw in the movie. And when he came with this, “Xipaia” — he came to me and said, “I had a dream with these birds, and I had a dream that I was making this headdress for you. And I thought it was for me in the beginning, but actually it was for you. So, this is a cocar that belongs to you.” And he gifted this to me.

And I don’t wear any other cocar, only this one. And it was blessed and sacred and protected by the guardians of the forests, through the mother of Alcebias, who’s the guy who was shot with the rubber ball. And she is a shaman woman, and she has a lot of wisdom. And she’s also in the movie protecting me, showing her protecting me. And the bird he dreamed was the hawk and the macaw. The hawk is inside, and outside is the red macaw.

And this brings the protection and the forest together to help me connect. It’s not just an accessory. It’s not an earring. It’s protection. It’s the forest with me. It’s the wisdom with me. It’s bringing the territory with me whenever I go somewhere. When I put the headdress down, I’m reconnecting with my origins and bringing this protection and strength with me. It’s a way that I can also greet and show respect and respect to other people around me.

AMY GOODMAN: And the painting on your face, your eyes, the red paint from your eyes across your temples, and then the black line from your lips to your ears, their significance?

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] Yes, they do. Every time that we go to — mainly, to defend the territory through some action, we paint our bodies. We prepare ourselves. It’s not just girl. There are specific paintings when you are children, when you’re adult, when it’s a marriage, for grieving. And it’s a way of asking for protection.

This specific painting, the red is urucum. It’s something that I carry with me since 2017. It comes from Acre, from the Ashaninka people. It’s very special. It lasts a long time. And it’s what I use not just to be beautiful, but to bring the protection of that territory and our ancestors. And the black one is the jenipapo, which is also a fruit. Urucum is also a small fruit. We use to body paint, also for medicine, and also to use in food. And jenipapo, the black, it’s also a fruit. And we use for medicine, as well, and food and also body paint. I didn’t bring the jenipapo, because we can’t bring the seeds here; otherwise, I’ll show it to you. But this is a way also of not only paint your body, but to strengthen and resist.

AMY GOODMAN: This is a story about your fight for the Amazon, for your people, for the land, defending the land. And it’s a love story between you and your husband, Hugo Loss, who works for IBAMA. And here, I want to ask you about the new president, about President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. He is the person who set up IBAMA, which is what Hugo is involved with, going after illegal miners. So, first, talk about Lula and the difference he has made when it comes to defending the rainforest.

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] One of the things that I learned, especially after being in the government, which was a place where I never — a space I never thought that I would be, I learned, since I was there because of the birth of the ministry — so, Sônia Guajajara invited me, and I — at first, I thought —

AMY GOODMAN: The Ministry of Indigenous Affairs, the first one ever in Brazil, that Sônia Guajajara is the head of?

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] Exactly. So, my biggest concern to be in the ministry was to be part of government. I never thought that I would be part of the government, because we were in — we were fighting against the Bolsonaro government. And we kept seeing big projects coming into the Amazon and other Indigenous territories and projects that were impacting the territory, so our relationship with the government was never friendly. It wasn’t ever good. Much the opposite, it was always very violent.

So, as much as Lula is different as a president, even though we were very insecure about that, but when I had a talk with Minister Sônia, we thought this is a different moment. We are — we weren’t just working for the government, Lula government. We were working for the peoples. And it was something that we earned because of all the movements and fights and things that we did and partnerships that we had, that actually helped us to have that ministry created. And Lula committed himself with the Indigenous peoples and defending the Amazon.

But one thing that I learned, being in this space, being part of the Ministry of Indigenous People, I learned that the structure of the government is very Bolsonarista independently, if it’s Lula or Bolsonaro in power. So, it wasn’t Bolsonaro in seat, per se, but there are a lot of people inside the government with the same train of thought, with the same kind of thinking, taking — in very high positions inside the government. So I saw that from very up close, the difficulty of Lula implementing public policies for Indigenous peoples, and also the defending of the Amazon and deforestation and expelling loggers.

When we come to this new government of Lula, we have a country that has been abandoned in relationship to Indigenous public policies. So it was a big challenge to be there. So we needed a lot of collective strength and collective — organization strength from IBAMA, FUNAI, because in the previous government, they lost their structure. People were fired. People were expelled. And they were monitored by the intelligence agents in Brazil. Like, Hugo was persecuted, and other defenders and agents from IBAMA, but other Indigenous leaders were being tracked by the government.

So, we come to the Lula government. Lula, it wasn’t just about acting against this violence and stop deforestation, but it was also structuring institutions like IBAMA and FUNAI and the federal police that lost resources because they were trying to end these institutions in the previous government. So, in relationship to Indigenous people, one of the things that we’re very clear, that we wouldn’t be able to resolve all the problems and violence in the Indigenous territories in four years of government, but we can start.

And what we saw inside the government Lula that was different is that they act very different. Bolsonaro used to strengthen the institutions that he used to invade our territories, while Lula, there is a decrease in deforestation in the Amazon. We have demarcated territories. We had some people being expelled from mining. But this is far from the ideal vision, not only about territory Indigenous, but we — when we talk a broad way of talking about the planet, when we talk about what the Amazon and other biomes do for the world, goes beyond Brazil. So, of course, that we need committed people in the defense of the territories and our rights and demarcation of our territories. This is paramount. But the big difference between Lula is this. But does this resolve all the problems? No, it does not. But we also have — we also have approval from the government fracking in the mouth of the Amazon River.

But the big difference is, today, we’re not only at the streets protesting. We’re also inside the government, building our own public policies according with our own needs, in our own Indigenous perspective. So, the fight continues beyond government. Beyond the government, we want the ministry to exist. We want our public policies that support our territorial needs. But our perspective is to continue in the government advancing our policies to support grassroots communities, Indigenous communities in the territories. Whether a new government, a new Bolsonarista comes back, we need to continue. So, independently of government, our fight continues.

AMY GOODMAN: Richard Ladkani, can you set up this next clip? You know, it is amazing that you were able to accompany Hugo Loss, the husband of Juma, on this police action in the Amazon. It is so incredibly dangerous, what he and his team face when they go after illegal miners.

RICHARD LADKANI: Yeah, so, it’s like the Environmental Protection Agency of Brazil. So they’re like government special forces that are allowed and capable to go into the Amazon. They have a team of very specially trained soldiers that go heavily armed against illegal mining sites, often giant gold factory ships that suck up the mud of the river, and then bind the mud with mercury. So they poison the rivers to get the gold that binds with the mercury. And these machines need to be destroyed.

So, Hugo goes in with his team and tries to do what he can on these missions to kind of mitigate risks to the environment, and it’s very, very dangerous. Often these places are run by cartels, heavily armed. So, when they arrive, they don’t know if they’re going to be fired at, if, you know, there’s going to be real resistance. Very often they run off into the forest, but I’ve seen them shoot back out of the forest. So, what they do sometimes is to use tear gas to first clear the area of people, to mitigate risk, but it’s very dangerous.

I’ve been on four of these missions. They’re like two weeks long. You sleep in the forest. You sleep in the jungle or on a beach somewhere. But it’s highly effective. It’s highly effective. And IBAMA has been extremely successful since they started, by actually bringing down the illegal mining and also deforestation that is attached to that by 50% since they started under the Lula government. So, that’s the clip.

AMY GOODMAN: So, this clip in Yanuni features Juma’s husband, Hugo Loss, who is head of special operations for IBAMA, Brazil’s main environmental agency.

IBAMA AGENT 1: [translated] Go, go, go!

IBAMA AGENT 2: [translated] The oxygen tank is going to explode.

IBAMA AGENT 1: [translated] Damn! Let’s go. Go!

HUGO LOSS: [translated] It’s stuck! Who did this [bleep] here?

IBAMA AGENT 3: [translated] That’s strong as hell, [bleep]!

IBAMA AGENT 1: [translated] Shoot with the rifle.

Jump over here, everyone.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that’s a clip from Yanuni. Richard, describe, especially for our radio audience, who was just hearing the noise. We’re looking at a fire.

RICHARD LADKANI: Yeah. So, what happens is they bring in these mattresses that they find on ships, and they put them onto the machine of the — like the engine of that ship. And they place oxygen tanks that they find also on the ship below these mattresses, so when they start lighting it up, they want this ship to explode, so that the engine is destroyed for good and can never be used again. But what happened in that moment was there was something wrong with the chain that tied our boat to the ship. It jammed. And as they had already started to fire, you could hear the danger rising, and you could feel the pressure mounting. But we couldn’t get away, because the boat was chained, and the chain jammed, and we couldn’t get it off. So they started — they couldn’t approach anymore, because the fire was too hot. So everyone started shooting at the chain from a moving boat. They were using a machine gun, a shotgun, pistols. They must have fired 50, 60 shots to get away.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, they’re not shooting the people. They’re blowing up these mining sites.

RICHARD LADKANI: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Who are the people?

RICHARD LADKANI: So, the people that work on the ships, they’re usually very poor people from the surrounding villages that volunteer — not volunteer, that get hired for very low pay. They maybe make $20 a day or $30 a day. But they are hired by these cartels. And so, IBAMA never arrests these people. They just want them to run off and go back to their villages. What IBAMA does is that they destroy the machines, that cost $200,000, $300,000, one ship like that. So it really hurts the cartels when they are able to blow up 20, 30 ships or so in 10 days.

AMY GOODMAN: And how many are there in the rainforest?

RICHARD LADKANI: How many of these ships?

AMY GOODMAN: Yeah.

RICHARD LADKANI: Thousands. Thousands and thousands. There’s probably 3,000, 4,000 mining sites across the Amazon, and each one has, like, maybe 10 ships, you know, around the area. So, it’s a total mess. And, you know, it’s very hard to destroy.

AMY GOODMAN: And, to say the least, very dangerous. This is another clip from Yanuni featuring Juma.

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] Are those who have lived for so many centuries inside these concrete boxes even capable to feel our suffering, our pain? I really don’t know if they’re even listening to us. Are you listening to me?

AMY GOODMAN: A clip from Yanuni. So, Juma, you have come to the United States, where this film, that you have also produced, is shortlisted for an Oscar. From here in our New York studio, you’re flying to Los Angeles and then to San Francisco for all of these screenings of Yanuni. Share your message, and also talk about the title of this film. Talk about Yanuni.

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] First of all, it was a big surprise for me. I never imagined to be the character of a movie or a producer, much less to be here in the United States with you and and bring Yanuni and to echo the voice of the forest to the world. When the invitation to be in this project came, I immediately said, “No. Why am I keep speaking? Why keep denouncing these great projects if people are not listening? How many times have I denounced violence, murder attempt and also violence against leadership and also sexual violence against women and children within this context of big projects entering territories?”

So, all this process of violence, until Richard sees me and finds me and proposes about this project, I thought, “No,” because every time that I believed in media and other people from around the world, when people came to me and Belo Monte Dam was being built, the entire world was talking about Belo Monte. Many people from the media were there, and everybody was interviewing me and other leadership, will say — they would come and say, “We’re going to share your voice to the world. We’re going to denounce.” But on the every basic day, daily, I couldn’t even cross the street. The constant violence against me silenced not only me, but many other women and other leaders.

My territory is in the region of Altamira, that for many years was considered the most violent city in Brazil. And all of that made me question. All the time that I spoke, I suffered violence and silencing. Why would I believe in this project? Why would I believe that this project would work? So, my feeling and the initial feeling was of frustration and distrust. And I kept saying, “I need to stay silent so I can stay alive.” And that moment, I wasn’t even with my children, because I needed to be safe, so it was a moment where I believed that being in silence was synonymous to being alive.

And when Richard comes to me and talk about this project, one of the things that caught my attention was, “Juma, I don’t have a script to present you. I want us to build this together. I want you to lead. I want you to feel that this is your project. What do you want to say to the world? You can do that. I want to do this with you. I don’t want to just do a movie about the Amazon.” And I thought, “This is different. I believe in this. I believe people being — Indigenous people being consulted.” So I saw this an opportunity to speak to the world, not only to denounce, but also to show that the Amazon and this violence is not a story. It’s a reality. It’s not in the past, that it’s still present.

People and leaders like me, they are impeded to go to the university and also to the free will to just go and also get health. So, what I really wanted right now was to be in my territory and be with my family. I wanted to be able to finish my medicine program to take care of the people in my territory. This is all I wanted. I didn’t want it to be like protesting in the streets of Brasília or any other part of the world. I really just wanted to have the right to be woman, youth, daughter and mother, and to exist in my own territory as it was in my childhood.

So, not only having our rights denied, but also living under threats, I understood that it wasn’t just about me. It was about all other Indigenous peoples and leaders who were going through the same thing or even worse. So, to accept this project was to accept to break the silencing. It was to believe that, yes, we can reach other parts of the world and bring information. So, be as a producer, it wasn’t just about the name or about awards. It was about staying alive. It was thinking about how to bring the voice beyond the Amazon and Brazil, and bring it to the world, and say Indigenous people are considered vulnerable.

And all this threat that happens in the Amazon, it doesn’t start from the Amazon. It comes from other gray financing and projects that come to our territory, saying that it’s development, but what actually happens in my community is destruction that these projects do, and we are there. The dam, the energy, the development, to them, doesn’t come to our territory. It goes to big corporations. It goes to outside of the Brazil. It goes to banks, banks that are financing these projects. So, the only reason we only have strong territories right now, because the big development are destroying our territories, not only in Brazil, but the world.

So, our vulnerability is caused to divide our people, to exploit our last natural resources that exist in the Amazon and in Brazil. But places like this are becoming more and more rare and disputed. And that’s why, when we talk about government, most people say that Indigenous people are bearing government plans, are a problem to government plans, because we don’t see development as the same thing. Development, to me, is quality of life, is being able to be with my family. It’s to be able to eat food without toxins, and clean water. It’s my kids being able to go to the river and bathe, and not just see mud, which is what’s happening to the rivers in the Amazon. And it’s not just about our lives. It’s all kinds of lives that have the right to exist like mine and yours. Many species, we’re losing. And that’s why we are in complete disequilibrium.

And Yanuni, it’s a call. It’s a call to action. It’s a call to say to defend the Amazon and to save these sacred territories and these last natural resources is not just my responsibility or responsibility of Indigenous people. It’s our responsibility. It’s our life that is at risk and at stake. This is what’s at stake at big tables, where big governments are deciding about our lives and deciding our future.

And that’s why I accepted to be part of this movie, because it’s a way to communicate, a way to get support. There’s no way to defend the territory today the way I used to do when I was a child. Our canoes and our bow and arrows are not enough, because today we fight against organized crime that are fully armed. They have draggers that cost like 3 million. We deal with people with a lot of resources that are doing this exploitation inside the territories. And that’s why I’m here, that I believe, for many reasons, I need to say this fight, it’s not fiction. It’s not romantic. It has serious consequences.

And I remember some moments in my life as me, as a woman and mother, I was very afraid, and many times I felt like giving up, because I kept asking myself, “What else do we need to do?” And you reminded me with your look, a look at a very special person I had in my territory. That was Jane Goodall. There was a moment that she was there in the territory talking. And I asked her why — at that age, I was so scared for her. When we went to the forest, she got out of the boat. She didn’t want anybody’s help to get off the boat. She just got off the boat by herself and entered the forest. And my dad was like, “What the heck is she doing? Somebody needs — somebody’s gonna get her.” I was afraid that the jaguar was going to get her. And she was just like, “I’m fine. The jaguar won’t get me.” And I’m like, “Oh my god! Why was she so stubborn in that moment?” We were trying to accompany her, and on the other side, other way, we were like, “Wait.” She was more than — she was older than 80 years old, her mental health better than many youth people, with so much physical disposition. She was in my territory.

And talking with her, it was so — it made all the difference for me, because I was questioning myself: “Why do I have to leave my territory, leave my family? I just want to be here. I just want to be able to just live and not just only fight and resist. I’m tired of this. I want to be able to live as a normal person.” And this conversation with Jane was — made me realize I couldn’t feel tired, I couldn’t lose hope, because that woman, with that age, still have dreams and hope, made me realize — it renewed my sense of life and to believe in me as a woman and in a better future, and not only look at the threats, but also look at the future with hope. And that changed my life.

And I believe that it’s exactly that I am doing here, to believe that Yanuni can reach the world with this message. And don’t let threats and tiredness be stronger than me, my ancestors taught me. I saw that in an Indigenous person — non-Indigenous person, as well, like I saw in my ancestors. She also inspired me, and not only me, but I think she inspired many people. And it’s with this commitment that I come here with Yanuni and Richard and Hugo and all the crew from the movie.

AMY GOODMAN: And Yanuni is the name of your newborn little girl.

JUMA XIPAIA: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Before we go, I just wanted to ask you to respond to what happened in Venezuela in the last days. Here you are in the United States. President Trump has just abducted the Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. He says Latin America, that this is our hemisphere. He will run Venezuela indefinitely. If you can respond as an Indigenous woman from next door, from Brazil?

JUMA XIPAIA: [translated] I think that his interest is not to govern Venezuela. It’s not. He’s not trying to free Venezuela from the narcotraffic. This is his excuse. He wants what’s under the soil in Venezuela, which is oil and the natural resources. This is his only objective, to invade and take a territory that does not belong to the United States, to interfere.

You know, I don’t agree with Maduro’s government. This is not what I’m defending. My vision, my perspective goes beyond government. It’s not about United States and Venezuela, Trump or Maduro, but my way of seeing this is to see this process of invasion and colonization and to steal our territory, our resources, ending any way of sustainable life. So, all the impacts that Venezuela is suffering and is coming, as well, it’s not going to just stay in the borders of Venezuela, Colombia and Brazil. It will be a world impact. It will be a planetary impact. We’re all going to suffer the consequence of this.

We’re talking about places that has the greatest portion of natural resources on the planet. So these places are being taken, forced taking, armed taking, not with the objective of protecting humanity or the peoples. The only objective is to explore and to take the wealth of that territory, not only from the Venezuelans. And this is very dangerous. If you look to Venezuela, it’s the same process of invasion and colonization of other countries, and that, for sure, the goal is not just to take Venezuela. The impact, just it’s going to impact the world economy. We have an impact, because even in the COP30 final letter, we didn’t even mention an even Trump sanctioning 60 organizations from the U.N. This is all about the exploration of all natural resources.

And with this exploration, you see that the planet is exhausted in resources. When a woman have a child, we need time to recover our body, to heal our wounds, to be strong again. How long does the planet have to recover itself? You don’t frack petrol in one or two years. It takes a long time for them to come back. And we don’t have that time on this planet. When you look at this line of production, we don’t have that time to clean the impact of this project. Venezuela also has Amazon. There are rivers in Venezuela that also reach Brazil. So, the impact is not only the economy, world economy, but we will have a climate impact. So, the climate injustice is not just for Venezuela. It’s for the world, the planet as a whole.

So, the people that are watching this on TV or reading that as news, it sounds like it’s not their problem, as if this is not reaching them. But it will. It will reach beyond the borders of Brazil and all borders of the world. So, yes, we all should care and be bothered about what’s happening right now in Venezuela, because what’s going to be the next country that this story is going to repeat itself?

So, I’m not surprised by what’s happening, because when you look at timeline, it’s the same exactly that is happening. The big difference now is that we don’t have a lot of time like we had before. Our time is shortening. So there is a way we need to start talking and act and support, be in a network of support and help to protect who protects. So, there is a way that we can organize ourselves as society, because people keep thinking that the politicians are the one that have power. The power is in the people. The power is in us. So we need to rise up, not to go to war, but to have hope and to change this context and to think about the collective well-being, and not think just about economy and the exploration of natural resources.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you, Juma, for joining us, as well as Richard Ladkani. Richard Ladkani is the director of Yanuni, the film that features Juma Xipaia, the Indigenous activist and land defender in Brazil. The film has been shortlisted for best documentary feature in the Academy Awards, and Juma is also a producer of that film. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

Media Options