Soldier, Journalist, Author, Fabulist, Critic, Satirist

Born June 24, 1842, Along Horse Cave Creek, Meigs County, Ohio

Died Date and place unknown, presumably in Mexico in late 1913 or 1914

The life of Ambrose Bierce is bracketed in mysteries, for no one knows where he was born (precisely) nor where or when he died. He was at once a realist and a fantasist, states of mind combined nowhere else as in "An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge." From a life of horror, bitterness, and tragedy, Bierce forged lasting works of art and fierce humor. He contributed equally to journalism, composition and usage, satire, naturalistic fiction, and--conversely--stories of the supernatural. His book, The Cynic's Word Book, better known as The Devil's Dictionary (1906), is an indispensable work, especially in the current age of prickly feelings and political correctness. In this election season, it's edifying and enlightening to read a few definitions from Bierce's book:

CAPITAL, n. The seat of misgovernment.

DEBT, n. An ingenious substitute for the chain and whip of the slave-driver.

PLATITUDE, n. The wisdom of a million fools in the diction of a dullard.

POLITICS, n. The conduct of public affairs for private advantage.

SUCCESS, n. The one unpardonable sin against one's fellows.

TWICE, adv. Once too often.

VOTE, n. The instrument and symbol of a freeman's power to make a fool of himself and a wreck of his country.

WALL STREET, n. A symbol of sin for every devil to rebuke.

The critic Carey McWilliams made his case for Bierce with these words:

[H]e wrote a half dozen of the finest American short stories, a dozen or so of the most memorable letters and battle pieces, some of the best American satiric verse and . . . he was the greatest American satirist in the classic tradition.

Kurt Vonnegut (another Hoosier) had this to say:

I consider anybody a twerp who hasn't read the greatest American short story, which is "Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge," by Ambrose Bierce.

Part Edgar Allan Poe, part Stephen Crane, part O. Henry, part H.L. Mencken, Ambrose Bierce was wholly himself, an American original and an uncategorizable author.

* * *

Weird Tales published just one work by Bierce. It's called "The Damned Thing," and it appeared in the first year "The Unique Magazine" was in print. It would be wholly inaccurate to say Bierce was only a peripheral figure in the history and development of weird fiction however. Before getting to the main point, we should note that Bierce was separated from Clark Ashton Smith by a single generation of poets, for Bierce was a mentor to George Sterling (1869-1926), the California poet and San Francisco bohemian who was himself a mentor to Smith (1893-1961). I wonder if Sterling's suicide in 1926 could have been a prod to Clark Ashton Smith, for most of his submissions to Weird Tales came after that date. In any case, Smith distinguished himself among contributors to "The Unique Magazine" with his scores of fantastic poems and stories.

As another sidelight, consider the case of Adolphe de Castro (1859-1959), aka Adolphe Danziger (and other aliases). A Polish Jew who immigrated to the United States in 1883, Danziger was at various times a rabbi, dentist, journalist, teacher, publisher, lawyer, and diplomat. Like George Sterling, he sought the advice and guidance of Ambrose Bierce while living in San Francisco. The two men even formed a publishing partnership and collaborated on the story "The Monk and the Hangman's Daughter." Well after Bierce's disappearance and presumed death, Danziger approached H.P. Lovecraft with a planned memoir on the departed author. After some delay and with some revisions and other work by Lovecraft and his friend Frank Belknap Long, Danziger published his Portrait of Ambrose Bierce in 1929. Reviews were mixed. Nonetheless, Danziger, as Adolphe de Castro, also collaborated with Lovecraft on two stories for Weird Tales, "The Last Test" (Nov. 1928) and "The Electric Executioner" (Aug. 1930). I should add that the collaboration seems to have been no such thing: Lovecraft simply reworked de Castro's ideas, effectively functioning as a ghostwriter. You can read more about the whole affair in an article entitled "The Revised Adolphe Danziger de Castro" by Chris Powell, here, and in L. Sprague de Camp's Lovecraft: A Biography (1976).

To be continued . . .

Ambrose Bierce's Story in Weird Tales

"The Damned Thing" (Sept. 1923)

Further Reading

A simple search of the Internet will turn up a lot on Ambrose Bierce. A trip to a university library would likely keep you busy all day.

|

| The Classics Illustrated line adapted the work of Ambrose Bierce to the comic book format. The art is by Gahan Wilson, an artist of the macabre and the author of the last illustration to appear in the original Weird Tales magazine. |

|

| Bierce was also the author of Fantastic Fables, published in 1899, the same year in which George Ade published his famous Fables in Slang. The fable of course is an ancient form, but the form lent itself to twentieth century practitioners such as James Thurber, George Orwell, Don Marquis, and Franz Kafka. |

|

| Here is the dust cover for a Caedmon Record of David McCallum reading "An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge" and "The Damned Thing." Thanks to Garrick for the image. |

|

| Ambrose Bierce and Adolphe de Castro collaborated on an adaptation of the story "The Monk and the Hangman's Daughter." De Castro went on to publish a memoir of his relationship with Bierce and to collaborate with H.P. Lovecraft on two stories for Weird Tales. |

|

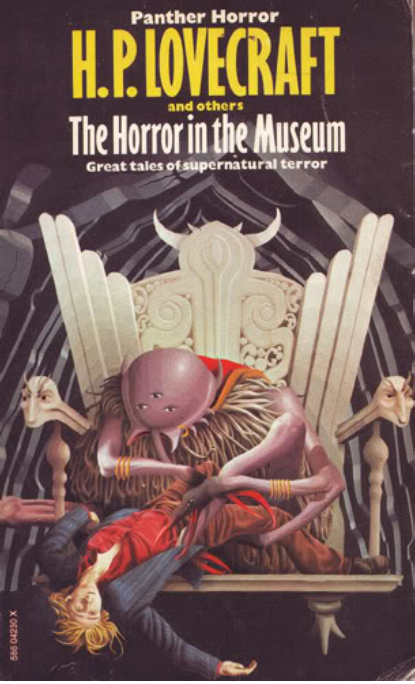

| Those two stories--"The Last Test" and "The Electric Executioner"--appeared in book form in The Horror in the Museum. Here's a paperback version, a British edition that may or may not contain all the tales from the original Arkham House edition. Can anyone attest to its contents? And does anyone know the name of the cover artist? |

|

| A stamp with a portrait of Ambrose Bierce, described as "immensely attractive . . . handsome, debonair, erect, and in the habit of looking out and over life, so to speak, as from an eminence." |

Text and captions copyright 2012, 2023 Terence E. Hanley