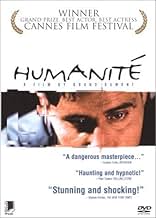

When an 11-year-old girl is brutally raped and murdered in a quiet French village, a police detective who has forgotten how to feel emotions--because of the death of his own family in some k... Read allWhen an 11-year-old girl is brutally raped and murdered in a quiet French village, a police detective who has forgotten how to feel emotions--because of the death of his own family in some kind of accident--investigates the crime, which turns out to ask more questionsWhen an 11-year-old girl is brutally raped and murdered in a quiet French village, a police detective who has forgotten how to feel emotions--because of the death of his own family in some kind of accident--investigates the crime, which turns out to ask more questions

- Awards

- 3 wins & 3 nominations total

- L'infirmier

- (as Daniel Leroux)

- Le policier anglais

- (as Robert Bunzl)

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

You get a shot of Pharoan looking at his boss's collar. The shot of the collar holds long enough for you to think "Hm, he sweats a lot." The shot holds long enough for you to think "okay, I got that, thanks. He sweats a lot." Then it holds long enough for you to think "All right already! Go wake up the editor."

A sequence like that would not be a problem when the cinematography is particularly good, except the cinematography in this film is not. It is competent, straightforward, unstylized, perhaps even dull; in other words, the cinematography serves the story perfectly.

The sedate pacing might not be a problem with different cinematography, which would affect the story for the better: the film is a psychological exploration, yet the people we're meant to sympathize with are typically shown in long shots or in closeup but with largely unchanging expressions. If something is going on behind the eyes, we can only guess what it is; and from the slack-jawed expression, we guess that what it is might not even be particularly profound. Wounded, yes, sad, yes, but we've seen that before and better, and it's nothing new. We need a reason to care *this time*, and for many people that reason won't be there.

The main character is a cipher, perhaps deliberately so, but the result is a film that doesn't tell you anything, and doesn't even tell you why it doesn't tell you anything--not the nihilism or the weary practicality of some noir films, but merely a bloated anecdote with an obscure or missing point. Unfortunately the anecdote, aside from being quite slow, is also almost completely humorless. The result is a film only for people with extraordinary patience and good will.

In L'Humanite, by Bruno Dumont (La Vie de Jesus), Pharaon de Winter (Emmanuel Schotte) is a Police Superintendent called upon to investigate the murder and rape of an 11-year old girl. Flaunting almost every cinematic convention, the film is not about solving a crime but a 2 1/2-hour poem of mood, time, silence and spirit. Set in northern France in the director's hometown of Bailleul, the characters are unglamorous members of the working class. Dumont devotes long stretches of the film to simply observing Pharaon going about his life: eating an apple, tending his garden, watching a soccer game on television, interacting with his mother, or being a friend to his neighbor Domino (Severine Caneele), a rugged factory worker and her obnoxious bus-driver boyfriend Joseph (Philippe Tullier). He is an unlikely cop, a passive, stoop-shouldered, and empathetic man who would sooner kiss a prisoner on the lips or stroke his neck as browbeat him. Pharaon sees the suffering of the world and wants to hold it in his hands and stroke it. Schotte's performance is so expressive that his best actor award at Cannes was criticized because most people thought he wasn't acting, just being himself.

As the film opens, a man is walking in the distance alone across a grassy hill. Suddenly as the camera moves in for a close-up, he collapses in the mud and just lays there for a while. Is he dead or alive? Did he commit the crime? In the next scene, he is sitting in his car listening to harpsichord music and we discover that he is a policeman talking in a barely audible voice to his superior. The film cuts away to the battered body of an 11-year old girl, her torn and bloody vagina graphically shown as the police gather. Pharaon maintains the same anguished, enigmatic look on his face throughout that makes us uncertain if he is the murderer or the Second Coming of Christ. We know very little about him except that he "lost" his wife and child a few years ago, but it is never made clear whether he lost them or they lost him. Signs of passion or involvement are rare but come with a sudden ferocity, as when he is walking across the crime scene and starts to scream at the top of his lungs, a sound drowned out only by the passing Eurostar train.

L'Humanite is an involving and disturbing film that you cannot feel lukewarm about. It is profoundly moving but often agonizingly slow and virtually unwatchable in some of its graphic details (you may never want to have sex again after watching these mechanical exercises). The climax of the film is as perplexing as the beginning with an ambiguous resolution that I'm not quite sure what to make of. What I do know is that I felt as vitally alive watching this film as I did the first time that I saw Leolo by Jean-Claude Lauzon. L'Humanite is a breath of fresh air on the turgid cinema landscape and Dumont is as honest and challenging a director as I've seen in quite a long time. His film continually forces us to question what we are looking at and, as the title suggests, keeps bringing us closer and closer to the core of what makes us truly human.

Dumont makes his bleak, desolate vision obvious right from the start, with the horrendous discovery of a murdered and mutilated child left naked and bleeding in a stark, autumnal field. The image is both shocking and brutal; with Dumont giving us a punch to the stomach right from the very first frame with a lingering close-up of the wound and filleted body parts. It's an image that both establishes and surmises the film as a thematic whole; the loss of innocence being central both with the murder of the child and with the character of Pharaon himself. It is the idea of back-story and the fragile demeanour of Pharaon - and to an extent the evocative performance of non-professional actor Emmanuel Schotte - which anchors the film, giving the audience an emotional spectator. He is also our representation within the film, mirroring the feelings of the audience if not quite our actions. After the aforementioned discovery there are no macho heroics; Pharaon reacts on an emotional level unseen in films of this nature, running back to his car, tears streaming down his face, lost in a kind of detached melancholy that continues throughout the film.

Over the course of the film, the narrative continues to unfold at a slow and deliberate pace, though we quickly realise that the real detective story at hand is not necessarily about the murder of the child, but more importantly, what has happened to make Pharaon the way he is. Has Pharaon had some sinister part in all of this, or is he merely a constant observer. The idea of voyeurism is an important one in Dumont's work, with the camera rarely moving; always static, removed from the context of the scene and merely recording things for our benefit. This gives the film a greater degree of realism, though may be a little tiresome for viewers weaned on a more westernised approach to cinema, with one hypnotic scene in particular finding our central protagonist tending his allotment for what seems like the best part of fifteen minutes.

As the film continues to unfold, and the clues begin to add up, we realise that this isn't going to have a clear-cut, moralistic ending akin to a routine police/crime thriller. Then again, with a central character who lives at home with a controlling mother, who adores the woman who lives down the street and allows her boyfriend to belittle him at every available opportunity and often stands monosyllabic at the back of a room... how on earth could it? With L'Humanité (1999), Dumont has attempted to create a stripped down, bare-naked form of ambient cinema, in which it is the little character details and passages of silence, broken only by shocking violence and mechanical sex, that go towards creating the story.

The ending of the film continues in this same vein and acts as a sort of shocking epiphany, in which every action and subtle line of dialog that has occurred during the epic running time is suddenly given a whole new meaning. Dumont has proved with this, his second feature, that he can reach beyond the tiresome kitchen sink theatrics of his first film, La Vie de Jesus (1997) and incorporate distancing naturalistic techniques (no camera movements, no artificial light, non-professional actors, etc) to create a film that is both horrendous and intoxicating in equal measures. Though enjoy is certainly the wrong word to use with a film this bleak and confrontational, those amongst you who admire the work of forward thinking European auteurs like the aforementioned Michael Haneke, Gaspar Noé and Lars von Trier will certainly admire and appreciate Dumont's shattering tour-de-force.

Still, I managed to get quite a clear impression of the film which is in my opinion a superb one. Although many people find themselves puzzled by the characters (virtually everyone in the show i attended came out of the cinema looking almost personally insulted by the film) i think that if you know and love Dostoevsky's books you won't find them so hard to understand. Pharaon is simply Prince Mishkin. He is assulted by the bluntness and cruelness of existence and the crime he tries to solve - but is overwhelmed with humility, love and compassion to the world. While his friend make love in a way that seems almost like a rape he makes love to the world, to the clods of the earth. When he rides his bicycle his upper body seems to be moving as if he was making love. But most of all he feels diligent compassion to the world and it's assaulters. The film shows the violence everywhere. Pharaon sees this violence and with his deep gaze manages to disarm it (with protesters and with Domino). I think that Pharaon is a really great acting performance. Pharaon like Mishkin in Dostoevky's notebooks 'sees not in the faces of people but in their hearts.'. The investigation taking place is like an investigation of the inner self. Of the human soul, of humanity. It's a category against Humanity and Pharaon's who is the categor manages to find compassion to humanity. Its sort of like an 'apocalypse now' in rural france.

Did you know

- TriviaThe body of the raped little girl was a silicone cast.

- Quotes

[first lines]

l'inspecteur de police Pharaon De Winter: I'm coming.

- Alternate versionsItalian distributor BIM originally removed about 2 minutes of sex footage from the Italian theatrical release in order to avoid a 'not under 18' rating. When the press criticized this self-censorship attempt, the distributor reissued the film in its original, integral form.

- SoundtracksLe Vertigo, Rondeau. Modérément

from "Pièce de Clavecin"

Music by Pancrace Royer

Performed by William Christie

Courtesy of harmonia mundi

- How long is Humanité?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Release date

- Country of origin

- Official sites

- Languages

- Also known as

- Humanity

- Filming locations

- Bailleul, Nord, France(Village)

- Production companies

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Box office

- Gross US & Canada

- $113,495

- Opening weekend US & Canada

- $10,075

- Jun 18, 2000

- Runtime2 hours 21 minutes

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 2.35 : 1

Contribute to this page