IMDb RATING

7.2/10

15K

YOUR RATING

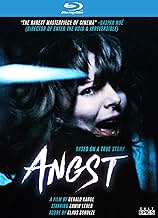

A troubled man gets released from prison and starts taking out his sadistic fantasies on an unsuspecting family living in a secluded house.A troubled man gets released from prison and starts taking out his sadistic fantasies on an unsuspecting family living in a secluded house.A troubled man gets released from prison and starts taking out his sadistic fantasies on an unsuspecting family living in a secluded house.

- Director

- Writers

- Stars

Robert Hunger-Bühler

- Off-Text

- (voice)

Silvia Ryder

- Daughter (Silvia)

- (as Silvia Rabenreither)

Karin Springer

- Daughter

- (voice)

Josefine Lakatha

- Mother

- (voice)

Helmut Hrdina

- Prison Guard

- (as Major Helmut Hrdina)

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

Angst is without a doubt one of the best serial killer flicks in the history of cinema. And some would say The Best. And I can tell you, it's damn close.

Angst follows a serial killer who is released from prison after a 10 year incarceration. What takes place is shocking and original film-making. What this man does is just start up where he left off. It's basically just following around the killer and just getting to know him. Oh and his victims, but in a more or less personal way. Eesh.

Angst excels in all facets. The acting by the main character, the serial killer, is flat out great, in an insane sort of way. He looks the part, and definitely acts the part. The scene when he's in the car is unforgettable. Throw in great cinematography, direction and writing, and the fact that this is a truly disturbing, realistic look into a serial killer's obsessive habits, it easily makes this one of the best serial killer movies of all time.

Angst follows a serial killer who is released from prison after a 10 year incarceration. What takes place is shocking and original film-making. What this man does is just start up where he left off. It's basically just following around the killer and just getting to know him. Oh and his victims, but in a more or less personal way. Eesh.

Angst excels in all facets. The acting by the main character, the serial killer, is flat out great, in an insane sort of way. He looks the part, and definitely acts the part. The scene when he's in the car is unforgettable. Throw in great cinematography, direction and writing, and the fact that this is a truly disturbing, realistic look into a serial killer's obsessive habits, it easily makes this one of the best serial killer movies of all time.

This relatively obscure German film is very well-done. It's about a schizophrenic man who murders uncontrollably. The film features very innovative camera work (at the time) which includes a recurring POV shot that will impress, no doubt. What makes this film tough to watch is the very realistic murder scenes, which include a graphic rape/murder and the long, drawn-out drowning death of an invalid. It reaches levels of intensity seen in other great psycho films like Seul Contre Tous and Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. The lead actor is very convincing, and makes you feel sorry for him as well as loathe him. A highly recommended film.

7pvsp

A very well photographed B-movie who puts the audience inside the mind of a compulsive killer. A strange film halfway between Michael Haneke for the story (I didn't know anything about the film and I thought It was haneke's one) and Stanley Kubrick for the cinematography (many references to "clockwork orange"). Actors performances are incredible considering they are dead half the film and their corpses are pulled and strechted across long single shots. An hypnotic movie with only narrative voice and great moments of cinema (especially the last action scene in the tunnel). One detail of importance : 22 years after the shooting, this film looks like it was shot last month. I wonder what became this director ? Any news ?

A very disturbing, chilling, thrill ride of movie made by what should have and or could have been a very interesting filmmaker. It really is a shame that Angst was the filmmakers only film. What direction would his career have gone? At any rate I really appreciate this movie and it's contribution to the genre.

Word on the street is this is a super intense, gruelling, claustrophobic serial killer film. They're not lying. But it's important to get to note why, especially in this case: why this type of violence enthralls so much? And I mean apart from any particular on-screen nastiness. More virulent films have been made, much nastier. Why this fascinates is a completely different beast than say, something like Hostel.

It's the easiest thing to make us cringe and shy away, but to fervently want to keep watching?

The popular opinion is this works so well exactly because of how contained and straight-forward. There are no distractions from the concentrated moment we first encounter: a inmate giving himself a shave on his day of parole. There are no allusions to anything else but private madness and nothing to escape to for comfort or respite, except perhaps sheer exhaustion. This man is going to go on a crime spree again as soon as he's out of prison, we can tell this much. We can tell it's going to unravel the way we secretly hope it does.

Well, this is fine and makes some sense. But doesn't adequately explain to my mind. No, why this works so viscerally - and ties in with other interests of mine in film - I believe has all to do with the cinematic eye.

Now most films operate on the assumption that you want to experience a world as real as possible. Every advance in cinematic technology - sound, color, the recent fad of 3D - is a step in that direction. We want to escape more vividly and more urgently than ever. And what most films do to abet that escape is to let loose a few threads of story and place, hopefully open enough if we are in caring hands, that we can be trusted to attach ourselves from own experience. The tighter the weave of the threads from that point on, the closer we are lassoed to the cinematic world. Editing and camera are assigned invisible ways; they have to work without us getting to notice.

The Soviets changed all that very early in the game. Here a very world was assembled by the eye. There was no story, it was all a matter of calligraphic (dynamic overlapping) watching. Welles, and less famously Sternberg before him, unpacked these notions by letting it fall on the eye of the camera to join fragments together.

(this particular eye was first conceived by the Buddhist but that's another story altogether).

Now this is rumored to be the DP's project working under an alias, a Polish man who knows the camera. The opening shot exhibits masterful knowledge of Welles; a crane shot that establishes location by joining together many different planes of perspective. It would have been a film to watch with just this mode, that others like Argento and DePalma exercised in adventurous flourishes of spatial exploration.

It's actually a little more elaborate than that. We have two eyes instead of the one. The first is the killer's eye, tightly screwed and always at eye-level as he prowls around. Interior monologue plays out in voice-over, itself taken from the diaries of an actual killer, and meant to recast everything as internal space: victims are an invalid, an old woman and her daughter, each one mapping to a person that deeply wounded in the past as we find out. So we have exceedingly tormented soul spilled out and contorting physical space, very much like Zulawski practiced. Another Pole, another piece of the puzzle.

The second eye you will notice is always mounted on a crane and pulled upwards in steep ascends. A bird's eye far removed from human madness, which is the Buddhist eye of woodblock prints. To the film's credit, and this is a lot of its power for me, it remains abstract enough that we may use this perspective as we are inclined: is it a godless and uncaring or a merciful eye, pulling us from the carnage or skipping to the next?

It's the easiest thing to make us cringe and shy away, but to fervently want to keep watching?

The popular opinion is this works so well exactly because of how contained and straight-forward. There are no distractions from the concentrated moment we first encounter: a inmate giving himself a shave on his day of parole. There are no allusions to anything else but private madness and nothing to escape to for comfort or respite, except perhaps sheer exhaustion. This man is going to go on a crime spree again as soon as he's out of prison, we can tell this much. We can tell it's going to unravel the way we secretly hope it does.

Well, this is fine and makes some sense. But doesn't adequately explain to my mind. No, why this works so viscerally - and ties in with other interests of mine in film - I believe has all to do with the cinematic eye.

Now most films operate on the assumption that you want to experience a world as real as possible. Every advance in cinematic technology - sound, color, the recent fad of 3D - is a step in that direction. We want to escape more vividly and more urgently than ever. And what most films do to abet that escape is to let loose a few threads of story and place, hopefully open enough if we are in caring hands, that we can be trusted to attach ourselves from own experience. The tighter the weave of the threads from that point on, the closer we are lassoed to the cinematic world. Editing and camera are assigned invisible ways; they have to work without us getting to notice.

The Soviets changed all that very early in the game. Here a very world was assembled by the eye. There was no story, it was all a matter of calligraphic (dynamic overlapping) watching. Welles, and less famously Sternberg before him, unpacked these notions by letting it fall on the eye of the camera to join fragments together.

(this particular eye was first conceived by the Buddhist but that's another story altogether).

Now this is rumored to be the DP's project working under an alias, a Polish man who knows the camera. The opening shot exhibits masterful knowledge of Welles; a crane shot that establishes location by joining together many different planes of perspective. It would have been a film to watch with just this mode, that others like Argento and DePalma exercised in adventurous flourishes of spatial exploration.

It's actually a little more elaborate than that. We have two eyes instead of the one. The first is the killer's eye, tightly screwed and always at eye-level as he prowls around. Interior monologue plays out in voice-over, itself taken from the diaries of an actual killer, and meant to recast everything as internal space: victims are an invalid, an old woman and her daughter, each one mapping to a person that deeply wounded in the past as we find out. So we have exceedingly tormented soul spilled out and contorting physical space, very much like Zulawski practiced. Another Pole, another piece of the puzzle.

The second eye you will notice is always mounted on a crane and pulled upwards in steep ascends. A bird's eye far removed from human madness, which is the Buddhist eye of woodblock prints. To the film's credit, and this is a lot of its power for me, it remains abstract enough that we may use this perspective as we are inclined: is it a godless and uncaring or a merciful eye, pulling us from the carnage or skipping to the next?

Did you know

- TriviaPig's blood, not stage blood, was used for the stabbing scene, for the sake of additional realism.

- GoofsWhen the daughter picks up the knife with her mouth it suddenly has changed into an upright position.

- Quotes

[first lines]

The Psychopath: The fear in her eyes and the knife in the chest. That's my last memory of my mother. That's why I had to go to prison for four years, even though she survived.

- Alternate versionsTwo versions of the film exist, the 87-minute version originally released to theatres and a 79-minute version that would be considered the director's cut. The longer version includes a prologue that was added by director Gerald Kargl in response to theatrical distributors who felt the film was too short. It includes a brief murder scene of K's first victims and a narrator recalling details of the man's youth, details which are mostly redundant with some of the narrative reflection later in the film. The shorter version, known as Kargl's preferred version, eliminates those eight minutes entirely.

- ConnectionsEdited into Erwin Leder in Fear (2015)

Details

Box office

- Budget

- €400,000 (estimated)

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content