Le journal d'une femme de chambre

- 1964

- Tous publics

- 1h 37m

IMDb RATING

7.4/10

10K

YOUR RATING

A sophisticated and self-assured woman from Paris joins a middle-class rural estate as a maid and causes quite a stir among the variously uptight, perverse and violent inhabitants.A sophisticated and self-assured woman from Paris joins a middle-class rural estate as a maid and causes quite a stir among the variously uptight, perverse and violent inhabitants.A sophisticated and self-assured woman from Paris joins a middle-class rural estate as a maid and causes quite a stir among the variously uptight, perverse and violent inhabitants.

- Director

- Writers

- Stars

- Awards

- 1 win & 2 nominations total

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

This is only my second Bunel film (The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie), and I am fascinated with the way he portrays the upper crust. here we have an odd family with some strange habits. Didn't you always think they were like that. It's the old joke about how you can determine class bu how two couples sit in a car. Lower class - men in front and women in the back; middle class husbands and wives sit together; upper class husbands sit with the other's wife.

Show fetishes, randy husbands, cold wives, rape and murder are all here amidst a fascist France. They are always going on about the republicans, ours would fit right in with the anti-semitism and xenophobia.

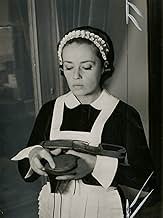

Among all this is the classic acting of Jeanne Moreau, a classy chambermaid, who is even willing to marry a fascist to prove him guilty of murder and rape. In the end, she turns out to be just an opportunist.

It would probably be more enjoyable knowing more about 1930s France, but it was still a classic.

Show fetishes, randy husbands, cold wives, rape and murder are all here amidst a fascist France. They are always going on about the republicans, ours would fit right in with the anti-semitism and xenophobia.

Among all this is the classic acting of Jeanne Moreau, a classy chambermaid, who is even willing to marry a fascist to prove him guilty of murder and rape. In the end, she turns out to be just an opportunist.

It would probably be more enjoyable knowing more about 1930s France, but it was still a classic.

The best thing about Bunuel is his ruthless lucidity, and it's thoroughly on display here. All his films start from the conviction that no one is to be pitied - or even if they are, Bunuel, like life, will not oblige, and neither the audience nor the person concerned should expect it of them. Which is not to say that all abuses are right - the film postulates that between fascist and violent criminal there is little difference, and then, true to lucid form, makes it clear at the end that evil does *not* automatically bring about its own destruction; a fact not to be lamented but fought over. Bunuel said he thought it was his most erotic film. It's not an unreasonable claim. There's not a single sex scene. Go figure.

Buñuel once said, "Bourgeois morality is for me immoral and to be fought. The morality founded on our most unjust social institutions, like religion, patriotism, the family, culture: briefly, what are called 'the pillars of society'."

I mention this, not to alienate people who might find such a statement offensive, but to suggest insight into his point of view. A viewpoint vigorously defended in this anti-bourgeois, rural tale that has a kick like a mule. Buñuel's truths are just as applicable today but, by putting them in 1930s France, he sweetens the bitter pill with a coating of sex, storytelling and the reassuring fiction that 'things have maybe moved on since then.'

Célestine impresses us. Intelligent, attractive and sophisticated - but she nevertheless needs to earn her living in service. She takes the train from Paris to work as a chambermaid at a country estate. In this lap of wealth, she deals with a panoply of dodgy people. A brutish handyman. A frigidly overbearing Madame Monteil. Madame's lecherous husband and her kinky father. Remarkably, none of these are portrayed as stereotypes. Characters are well fleshed out as Buñuel pits one against another. Madame Monteil earns our sympathy as she confides sexual shortcomings to the priest, who is in turn well-meaning if hopelessly out of touch. Doddering old Monsieur Rabour, although at first shockingly abhorrent with his fixation on women's feet, probably has nothing more harmful than a shoe fetish. "Would you mind if I touch your calf?" he asks (but goes no further up her leg). Is Célestine playing a dangerous game? Is she a libertine? Or just one step ahead of her audience?

The first half of Diary of a Chambermaid is delightful saucy comedy. Buñuel's famed surrealism, that make films like Un Chien Andalou or L'Âge d'Or so formidable, is nowhere to be seen. Nor do we have to grapple with the distanciation of Exterminating Angel, his Brechtian masterpiece of just two years earlier. But be warned, gentle reader. The second half is not only grislier, but by the end Buñuel will have pulled the rug from under your feet. It can be a bleak experience.

Quite apart from a clever story, Diary of a Chambermaid offers many delights, both to casual viewers and serious film analysts. Depending on your viewpoint, Moreau's many-sided performance is either a triumph for feminism or stands feminism on its head. It strips bare the bourgeoisie and capitalist, presenting the rising tide of French fascism as xenophobic intolerance - one we can recognise as replicated in many countries or patriotic cults even today. The hypocrisy of the upper classes is one of 'fur coat and no knickers'; whereas the pious protestations of the lower ranks are shown as the facade from which they lust after the coat itself.

Class-struggle is mirrored by sex-as-power. To men, sex becomes a celebration of might, whether physical, social or financial. To women, it is the potential to entrap with allure. She is always present and always unattainable. Through this implied promise of sexual gratification she bends men to her will. And still projects an aura of 'purity'. Our handyman tortures a goose before killing it rather horrible, but in a way does it add to his raw animal charm? And is Buñuel really just telling a story? Or is he manipulating his audience to drive the point home?

This is also Buñuel's only film made in anamorphic widescreen format. Although not showy, the cinematography is powerful. Credits open to the sound of a rushing steam train. We watch, through Célestine's eyes, the countryside flash by. A wide angle lens increases the sense of movement, as if we are propelled by an unstoppable force.

When Joseph tries to kiss Célestine at night by the bonfire, his posture is that of a vampire. A snail crawling across the a dead and violated body in the woods is as vivid and shocking as anything from Buñuel's earlier catalogue of slit eyeballs and dead donkeys. But it is Buñuel's acerbic vision of all that is wrong, in all layers of society, that is so chilling.

At one point, Monsieur Rabour is reading the French author JK Huysmans. Huysman's view of the world was as pessimistic as Buñuel, but it is Buñuel that makes it so all-encompassing. The festering fascist mob who cheer for Chiappe in our film, are honouring the same chief of police who prohibited Buñuel's L'Âge d'Or (after fascists destroyed the cinema where it was being shown). There were few governments that liked Buñuel, and we can see that the feeling was mutual.

The film is more political than it is entertaining, which may alienate some viewers who start off liking it. Even the title seems cynical I don't recall any suggestion of her keeping a journal. Diary of a Chambermaid is a great vehicle for Moreau, who gets to play so many characters in one. A criticism often levelled at mainstream cinema is that women tend to be decoration in male-driven plots. Célestine (or 'Marie' as she is called in another dig at Catholic - or class - depersonalisation) doesn't so much take over the driving seat as suggest a new perspective from which she is in control. Audiences will divide on whether they ultimately like her or not.

Things may have moved on. Domestic service is less harsh in most parts of the world where it survives today. Fascism has been replaced with virulent if not yet such obvious forms of rampant and aggressive nationalism. Sex is not always a game of power. But forces of immorality still pose in white robes and high office. 'Commoners' still aspire to the evils they decry. The purity of a saint is maybe needed to 'enjoy' Diary of a Chambermaid. But Buñuel stood up for his beliefs. Today, most viewers may content themselves with standing up for his cinematic skills.

I mention this, not to alienate people who might find such a statement offensive, but to suggest insight into his point of view. A viewpoint vigorously defended in this anti-bourgeois, rural tale that has a kick like a mule. Buñuel's truths are just as applicable today but, by putting them in 1930s France, he sweetens the bitter pill with a coating of sex, storytelling and the reassuring fiction that 'things have maybe moved on since then.'

Célestine impresses us. Intelligent, attractive and sophisticated - but she nevertheless needs to earn her living in service. She takes the train from Paris to work as a chambermaid at a country estate. In this lap of wealth, she deals with a panoply of dodgy people. A brutish handyman. A frigidly overbearing Madame Monteil. Madame's lecherous husband and her kinky father. Remarkably, none of these are portrayed as stereotypes. Characters are well fleshed out as Buñuel pits one against another. Madame Monteil earns our sympathy as she confides sexual shortcomings to the priest, who is in turn well-meaning if hopelessly out of touch. Doddering old Monsieur Rabour, although at first shockingly abhorrent with his fixation on women's feet, probably has nothing more harmful than a shoe fetish. "Would you mind if I touch your calf?" he asks (but goes no further up her leg). Is Célestine playing a dangerous game? Is she a libertine? Or just one step ahead of her audience?

The first half of Diary of a Chambermaid is delightful saucy comedy. Buñuel's famed surrealism, that make films like Un Chien Andalou or L'Âge d'Or so formidable, is nowhere to be seen. Nor do we have to grapple with the distanciation of Exterminating Angel, his Brechtian masterpiece of just two years earlier. But be warned, gentle reader. The second half is not only grislier, but by the end Buñuel will have pulled the rug from under your feet. It can be a bleak experience.

Quite apart from a clever story, Diary of a Chambermaid offers many delights, both to casual viewers and serious film analysts. Depending on your viewpoint, Moreau's many-sided performance is either a triumph for feminism or stands feminism on its head. It strips bare the bourgeoisie and capitalist, presenting the rising tide of French fascism as xenophobic intolerance - one we can recognise as replicated in many countries or patriotic cults even today. The hypocrisy of the upper classes is one of 'fur coat and no knickers'; whereas the pious protestations of the lower ranks are shown as the facade from which they lust after the coat itself.

Class-struggle is mirrored by sex-as-power. To men, sex becomes a celebration of might, whether physical, social or financial. To women, it is the potential to entrap with allure. She is always present and always unattainable. Through this implied promise of sexual gratification she bends men to her will. And still projects an aura of 'purity'. Our handyman tortures a goose before killing it rather horrible, but in a way does it add to his raw animal charm? And is Buñuel really just telling a story? Or is he manipulating his audience to drive the point home?

This is also Buñuel's only film made in anamorphic widescreen format. Although not showy, the cinematography is powerful. Credits open to the sound of a rushing steam train. We watch, through Célestine's eyes, the countryside flash by. A wide angle lens increases the sense of movement, as if we are propelled by an unstoppable force.

When Joseph tries to kiss Célestine at night by the bonfire, his posture is that of a vampire. A snail crawling across the a dead and violated body in the woods is as vivid and shocking as anything from Buñuel's earlier catalogue of slit eyeballs and dead donkeys. But it is Buñuel's acerbic vision of all that is wrong, in all layers of society, that is so chilling.

At one point, Monsieur Rabour is reading the French author JK Huysmans. Huysman's view of the world was as pessimistic as Buñuel, but it is Buñuel that makes it so all-encompassing. The festering fascist mob who cheer for Chiappe in our film, are honouring the same chief of police who prohibited Buñuel's L'Âge d'Or (after fascists destroyed the cinema where it was being shown). There were few governments that liked Buñuel, and we can see that the feeling was mutual.

The film is more political than it is entertaining, which may alienate some viewers who start off liking it. Even the title seems cynical I don't recall any suggestion of her keeping a journal. Diary of a Chambermaid is a great vehicle for Moreau, who gets to play so many characters in one. A criticism often levelled at mainstream cinema is that women tend to be decoration in male-driven plots. Célestine (or 'Marie' as she is called in another dig at Catholic - or class - depersonalisation) doesn't so much take over the driving seat as suggest a new perspective from which she is in control. Audiences will divide on whether they ultimately like her or not.

Things may have moved on. Domestic service is less harsh in most parts of the world where it survives today. Fascism has been replaced with virulent if not yet such obvious forms of rampant and aggressive nationalism. Sex is not always a game of power. But forces of immorality still pose in white robes and high office. 'Commoners' still aspire to the evils they decry. The purity of a saint is maybe needed to 'enjoy' Diary of a Chambermaid. But Buñuel stood up for his beliefs. Today, most viewers may content themselves with standing up for his cinematic skills.

Bunuel's 'Diary Of A Chambermaid' was released in between two of his surreal masterpieces 'The Exterminating Angel' and 'Simon Of The Desert'. It is, on the surface at least, a lot more conventional as either of those, maybe that's why it doesn't get as much attention as it deserves. I don't know why it is rarely mentioned when people discuss the very best of Bunuel, but for me it's almost as great as 'Viridiana' and 'Belle De Jour'. The story was previously filmed by Renoir in the 1940s, but I haven't seen that version, so I can't say how different Bunuel's approach to the material is. As Bunuel claimed not to have seen it either I don't feel so bad. Jean Moreau, the beautiful star of Truffaut's 'Jules And Jim' and countless other Euro art film favourites, gives a brilliant performance as the enigmatic Celestine, maid to The Monteils, a very odd family living in pre-War France. Bunuel includes some of his usual comments about sexual deviance, and France's future under the Nazi occupation haunts the whole film, but what is most interesting to me about the picture is its subtlety and ambiguity. Like 'Belle De Jour' I think each repeated viewing will reveal more, and opinions on its meaning will depend on the individual viewer. Personally I'm still exploring Bunuel's extraordinary body of work. It is exciting doing so. I've probably only seen a third of his output so far, but I've yet to see a movie made by him that is less than fascinating. 'Diary Of A Chambermaid' just might be his most underrated film. I highly recommend it.

In the 30's, the witty, literate and quite sophisticated chambermaid Céléstine (Jeanne Moreau) comes from Paris to work for the dysfunctional Monteil family in the country, more specifically for the fetishist on shoes and maniac for cleaning Monsieur Rabour (Jean Ozenne). His daughter and mistress of the house Madame Monteil (Françoise Lugagne) is a frigid and arrogant woman, and her husband, Monsieur Monteil (Michel Piccoli), is a hunter and also a wolf with their maids. Their fascist and rude worker Joseph (Georges Géret) feels a sexual attraction for Céléstine, but she repels him. Their neighbor, Captain Mauger (Daniel Ivernel), has a problem with the Monteils and dumps his garbage in their yard, but Céléstine talks to him and is motive of gossips. When Monsieur Rabour unexpectedly dies, Céléstine quits her job but while in the train station, she finds that the girl Claire was found raped and murdered by the police. Céléstine returns to her job convinced that Joseph killed the little girl and trying to find evidences against him.

"Le Journal d'une Femme de Chambre" is a delightful movie of undefined genre drama, black comedy, adventure? where Luis Buñuel again exposes fight of classes, hypocrisy of both the bourgeois and the working class, a historical moment in France with the fascism growing, the ridiculous role of the clerical and an unsolved murder case. The story is centered in Céléstine, but the motives why a woman with her profile accepts a job in a rural area is never clear. The identity of the rapist and killer of Claire is also not disclosed, there is only a strong insinuation that Joseph killed the girl. The story is very ironic, like for example when Monsieur Monteil is informed that Céléstine and Joseph will marry and requires the sexual favors from Marianne; or the weird fetishism of Monsieur Rabour; or the priest asking for a new roof for the church to Madame Monteil; or the conclusion with Captain Mauger changing his will and serving the mistress and smart Céléstine on their bed. My vote is seven.

Title (Brazil): "O Diário de uma Camareira" ("The Diary of a Chambermaid")

"Le Journal d'une Femme de Chambre" is a delightful movie of undefined genre drama, black comedy, adventure? where Luis Buñuel again exposes fight of classes, hypocrisy of both the bourgeois and the working class, a historical moment in France with the fascism growing, the ridiculous role of the clerical and an unsolved murder case. The story is centered in Céléstine, but the motives why a woman with her profile accepts a job in a rural area is never clear. The identity of the rapist and killer of Claire is also not disclosed, there is only a strong insinuation that Joseph killed the girl. The story is very ironic, like for example when Monsieur Monteil is informed that Céléstine and Joseph will marry and requires the sexual favors from Marianne; or the weird fetishism of Monsieur Rabour; or the priest asking for a new roof for the church to Madame Monteil; or the conclusion with Captain Mauger changing his will and serving the mistress and smart Céléstine on their bed. My vote is seven.

Title (Brazil): "O Diário de uma Camareira" ("The Diary of a Chambermaid")

Did you know

- TriviaThis is Luis Buñuel's only film in the anamorphic widescreen format.

- GoofsAt the train station, Célestine is supposed to be returning to Paris but she's waiting on the wrong side of the tracks: In one shot, one can clearly read "Direction Paris" on the other side.

- ConnectionsFeatured in À propos de Buñuel (2000)

- How long is Diary of a Chambermaid?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Release date

- Countries of origin

- Language

- Also known as

- Diary of a Chambermaid

- Filming locations

- Production companies

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Box office

- Gross worldwide

- $126

- Runtime1 hour 37 minutes

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 2.35 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content

Top Gap

By what name was Le journal d'une femme de chambre (1964) officially released in India in English?

Answer