IMDb RATING

7.0/10

1.6K

YOUR RATING

Two male musicians fall in love, but blackmail and scandal makes the affair take a tragic turn.Two male musicians fall in love, but blackmail and scandal makes the affair take a tragic turn.Two male musicians fall in love, but blackmail and scandal makes the affair take a tragic turn.

- Director

- Writers

- Stars

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

This film deals with a prosperous man who encounters a sleazy blackmailer who discovers that he is gay. (This silent rarity is a good reason for film preservation!)

A much later film "Victim", deals with a similar subject.

A much later film "Victim", deals with a similar subject.

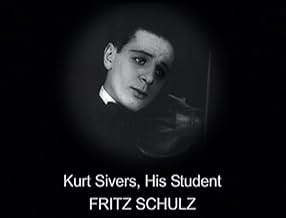

It is hard to vote for this film, because it is really just the shreds of a film. The odd thing is that ONLY the parts of the story relevant to gay sensibilities remain: the relationship between the violinist Paul Körner (Veidt) and his youthful protegé, the scenes of all-male partying, Paul making a pass at the man who turns out to be a blackmailer, and apparently the slide-show lecture on the sexual continuum (though perhaps this was reconstructed from the historical sexologist's actual slide shows?). Besides this, there is the skeleton of the legal plot: Paul reading about suicides and knowing what's behind it, the judge giving the blackmailer 3 years and Paul one week, and Paul coming home to kill himself.

What you don't see is any scene at all with a woman in it, except for one where young Paul runs in terror from a whorehouse. Evidently there were two sets of parents and a young woman all active in the original film, and they all ended up being cut from the final film.

There is not much development of the character of the boy Paul loves--it is not quite clear from the end whether he mourns Paul as a self-sacrificing friend, a great violinist, or the love of his life. Paul himself, in an extended flashback, evidently realized he was gay at the moment a whore kissed him; the fill-in titles explain that a young woman of dubious morals kissed the boy at a point after his story has disappeared from the surviving clips of the film. So presumably the boy has realized that, since he does not like being kissed by a woman, he must be gay and love Paul after all. It's an odd logic, redeemed only by Veidt's combination of sensuality and morality (great moment when he starts eagerly kissing a pick-up and then is horrified when the man asks for money).

Veidt is pretty amazing. The man played vampires or at least exotic sexual predators, Jews, Nazis in Allied films, a Devil's Island inmate--every kind of marginal monster; in one movie he seems to be playing Jesus. When he played kings, he played them mad and/or deformed. Yet he gave every character an edge, a dignity, a strength that made you feel it wasn't right if he got shot in the back. In this film, he looks rather like Cesare from Cabinet of Dr. Caligari but the same skeletal-elegant physique and haunted quality (and haunted makeup) become expressions of human sorrow, longing, and a frail nobility of character.

It is interesting to compare this film to Victim, made 42 years later. In both stories, the protagonist is a man who discovered and explored his sexual feelings for other men as a schoolboy; as a mature adult, having achieved a position of great prestige, he becomes involved in an unconsummated relationship with a much younger man who admires him passionately. In both stories, a law makes homosexuals an easy target of blackmailers, and both men attempt to defy the blackmailers and the law. In the 1919 movie, however, Körner, after attempting to redirect his sexual desires by various means, accepts himself as the way he is and lives a gay lifestyle (or so we may assume from his activities at the drag ball). When he is confronted with the prospect of marriage, he sends his parents or prospective girlfriend to a sexologist so that they, too, can accept him as he is. If he does not try to seduce his protegé, it is presumably from a sense that it would be wrong to exploit his position of power over a very young, indeed virginal, student (and the boy is horrified when he realizes that the relationship is potentially sexual). Melvin Farr, on the other hand, has succeeded in redirecting his sexual desires: he is married to a cool blonde and together they are confident that he is, if not completely heterosexual, completely monogamous. No gay bars for him. The boy with whom he is in love, on the other hand, is frankly gay and would like to seduce his hero. In both stories, the tragic "victim" is the man who, openly and unreservedly gay, is vulnerable to blackmail, tries to protect the man he loves, and finally kills himself. The earlier movie has a distinguished doctor arguing that there is a sexual continuum which is natural and good, and should not be subject to legal penalties or blackmail; the later movie just has examples of presumably good (eminent) men who happen to have secret homosexual sides, and the hero's nobility lies in going to bat for a working-class boy who could not keep his own sexuality secret.

I am struck by the fact that both the tragic victims look physically frail--thin, as if worn to a bone in the hope that if they turn sideways they will be overlooked by society. Both the ambiguously sexual survivors are heartier types, physically more solid and substantial, though of course Dirk Bogarde could out-edge even Veidt.

What you don't see is any scene at all with a woman in it, except for one where young Paul runs in terror from a whorehouse. Evidently there were two sets of parents and a young woman all active in the original film, and they all ended up being cut from the final film.

There is not much development of the character of the boy Paul loves--it is not quite clear from the end whether he mourns Paul as a self-sacrificing friend, a great violinist, or the love of his life. Paul himself, in an extended flashback, evidently realized he was gay at the moment a whore kissed him; the fill-in titles explain that a young woman of dubious morals kissed the boy at a point after his story has disappeared from the surviving clips of the film. So presumably the boy has realized that, since he does not like being kissed by a woman, he must be gay and love Paul after all. It's an odd logic, redeemed only by Veidt's combination of sensuality and morality (great moment when he starts eagerly kissing a pick-up and then is horrified when the man asks for money).

Veidt is pretty amazing. The man played vampires or at least exotic sexual predators, Jews, Nazis in Allied films, a Devil's Island inmate--every kind of marginal monster; in one movie he seems to be playing Jesus. When he played kings, he played them mad and/or deformed. Yet he gave every character an edge, a dignity, a strength that made you feel it wasn't right if he got shot in the back. In this film, he looks rather like Cesare from Cabinet of Dr. Caligari but the same skeletal-elegant physique and haunted quality (and haunted makeup) become expressions of human sorrow, longing, and a frail nobility of character.

It is interesting to compare this film to Victim, made 42 years later. In both stories, the protagonist is a man who discovered and explored his sexual feelings for other men as a schoolboy; as a mature adult, having achieved a position of great prestige, he becomes involved in an unconsummated relationship with a much younger man who admires him passionately. In both stories, a law makes homosexuals an easy target of blackmailers, and both men attempt to defy the blackmailers and the law. In the 1919 movie, however, Körner, after attempting to redirect his sexual desires by various means, accepts himself as the way he is and lives a gay lifestyle (or so we may assume from his activities at the drag ball). When he is confronted with the prospect of marriage, he sends his parents or prospective girlfriend to a sexologist so that they, too, can accept him as he is. If he does not try to seduce his protegé, it is presumably from a sense that it would be wrong to exploit his position of power over a very young, indeed virginal, student (and the boy is horrified when he realizes that the relationship is potentially sexual). Melvin Farr, on the other hand, has succeeded in redirecting his sexual desires: he is married to a cool blonde and together they are confident that he is, if not completely heterosexual, completely monogamous. No gay bars for him. The boy with whom he is in love, on the other hand, is frankly gay and would like to seduce his hero. In both stories, the tragic "victim" is the man who, openly and unreservedly gay, is vulnerable to blackmail, tries to protect the man he loves, and finally kills himself. The earlier movie has a distinguished doctor arguing that there is a sexual continuum which is natural and good, and should not be subject to legal penalties or blackmail; the later movie just has examples of presumably good (eminent) men who happen to have secret homosexual sides, and the hero's nobility lies in going to bat for a working-class boy who could not keep his own sexuality secret.

I am struck by the fact that both the tragic victims look physically frail--thin, as if worn to a bone in the hope that if they turn sideways they will be overlooked by society. Both the ambiguously sexual survivors are heartier types, physically more solid and substantial, though of course Dirk Bogarde could out-edge even Veidt.

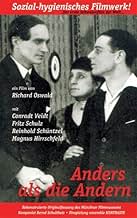

"Anders als die Andern" (Different from the Others) is a 1919 German film starring Conrad Veidt that was pieced together and shown at one point on public television.

About a law on the books that makes homosexuality a crime, it had a very short run in Germany before being pulled, and people who attended the movie were harassed.

The lead is played by a German actor familiar to American audiences, usually for portraying a bad guy, Conrad Veidt. Despite dying in 1943, Veidt had a nearly 30-year career in films. Here he plays possibly the first gay character in cinema who, with such a law in place, is a target for a blackmailer.

A very interesting film with a wonderful performance by Veidt. Only part of the movie remains, but it has been put together as well as can be expected - it is, after all, a mere 102 years old. It's amazing how relevant some of the material in it remains today.

About a law on the books that makes homosexuality a crime, it had a very short run in Germany before being pulled, and people who attended the movie were harassed.

The lead is played by a German actor familiar to American audiences, usually for portraying a bad guy, Conrad Veidt. Despite dying in 1943, Veidt had a nearly 30-year career in films. Here he plays possibly the first gay character in cinema who, with such a law in place, is a target for a blackmailer.

A very interesting film with a wonderful performance by Veidt. Only part of the movie remains, but it has been put together as well as can be expected - it is, after all, a mere 102 years old. It's amazing how relevant some of the material in it remains today.

It's a wonder any of this film exists; if not for the wear of age (it's said that most films of this era are lost), one would think censorship and the Nazis would have annihilated it. Yet, much of the footage remains. The Kino release of the reconstruction fills in the rest of the story with explanatory intertitles and still photographs, nearing the film's original runtime. That's the first wonder.

The second is its message of tolerance and understanding of homosexuals. Message films, social realist films, or "enlightenment films" were not too common in the silent era, probably because the lack of sound takes away from the capacity to lecture. Lois Weber is an exception that I'm familiar with; she made a career out of selling morals to audiences. "Different from the Others" includes the tact of a self-referential scene, which Weber broadened to more interesting depths in her best work. This is a film pleading for the equality of homosexuals, and it features a lecture within the lecture doing the same: the "sexoligist" Magnus Hirschfeld giving a slideshow presentation, which is attended by Else. I think it makes the film more honest, and, at the same time, it's a way for the filmmakers to be as blunt as possible.

It's difficult to appreciate the film aesthetically, anymore. The gay nightclub scenes are frank, but the film seems to shy away from too much intimacy between homosexuals. "Philadelphia" (1993) has been criticized for it's lack of a kiss, too, so I suppose it's asking too much of a film from 1919. The camera-work appears rather static, as well. On the other hand, Conrad Veidt was an admirable man and quite an actor. This is as much bravery from a prominent actor as you'll ever see. And, he was outspoken against the Nazis, as opposed to Emil Jannings, probably the other major male star of German silent film. Although Veidt's performance is much in the style of the time, he shows the right balance of effeminacy without being stereotypical.

Other than Veidt, the film isn't of much entertainment or artistic value. The film's message, however, is very important, even today; as the reconstruction introduction says, Germany, while a generally liberal government and populace today, Paragraph 175 wasn't repealed until 1994. And, there's the marriage debate in the US and elsewhere. "Different from the Others" is powerful in that way.

The second is its message of tolerance and understanding of homosexuals. Message films, social realist films, or "enlightenment films" were not too common in the silent era, probably because the lack of sound takes away from the capacity to lecture. Lois Weber is an exception that I'm familiar with; she made a career out of selling morals to audiences. "Different from the Others" includes the tact of a self-referential scene, which Weber broadened to more interesting depths in her best work. This is a film pleading for the equality of homosexuals, and it features a lecture within the lecture doing the same: the "sexoligist" Magnus Hirschfeld giving a slideshow presentation, which is attended by Else. I think it makes the film more honest, and, at the same time, it's a way for the filmmakers to be as blunt as possible.

It's difficult to appreciate the film aesthetically, anymore. The gay nightclub scenes are frank, but the film seems to shy away from too much intimacy between homosexuals. "Philadelphia" (1993) has been criticized for it's lack of a kiss, too, so I suppose it's asking too much of a film from 1919. The camera-work appears rather static, as well. On the other hand, Conrad Veidt was an admirable man and quite an actor. This is as much bravery from a prominent actor as you'll ever see. And, he was outspoken against the Nazis, as opposed to Emil Jannings, probably the other major male star of German silent film. Although Veidt's performance is much in the style of the time, he shows the right balance of effeminacy without being stereotypical.

Other than Veidt, the film isn't of much entertainment or artistic value. The film's message, however, is very important, even today; as the reconstruction introduction says, Germany, while a generally liberal government and populace today, Paragraph 175 wasn't repealed until 1994. And, there's the marriage debate in the US and elsewhere. "Different from the Others" is powerful in that way.

10Venarde

A frank story of homosexual love and tragedy made 85 years ago, featuring such amazing things as a same-sex dance hall and a drag ball as background to dramatic scenes. It still packs a wallop, thanks to its purpose as an impassioned plea for justice and a wonderful central performance by the Conrad Veidt. Kino has just released this reconstructed version of about 50 minutes, based in large part on a print discovered in Moscow, with intertitles and a few stills telling the rest. It's a an effective drama and a fascinating history lesson. A good bit is still missing, but the most amazing things turn up, so maybe more of Anders als die Andern will as well. To have this much is wonderful.

Did you know

- TriviaMagnus Hirschfeld, a prominent sexologist, co-wrote the screenplay and made a cameo appearance as The Doctor, with whom Paul Korner consults. A scene resembling that of the modern-day LGBT scene existed in Weimar Germany, albeit underground, and the scene at the gay bar featured actual LGBT individuals. The screenwriter and author Anita Loos said of this period, in 1923: "Any Berlin lady of the night might turn out to be a man: the prettiest girl on the street was Conrad Veidt, who later became an international film star." (It was Hirschfeld who coined the term 'transvestism.')

- Alternate versionsThere is an Italian edition of this film on DVD, distributed by DNA srl, "DIVERSI DAGLI ALTRI: Alle Origini Del Cinema Gay - Special Edition" (4 Films on a single DVD: Mikaël, 1924 + Fireworks, 1947 + Un chant d'amour, 1950 + Anders als die Andern, 1919), re-edited with the contribution of film historian Riccardo Cusin. This version is also available for streaming on some platforms.

- ConnectionsEdited into Gesetze der Liebe (1927)

- How long is Different from the Others?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Release date

- Country of origin

- Languages

- Also known as

- Different from the Others

- Filming locations

- Berlin, Germany(unknown scenes)

- Production companies

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

- Runtime50 minutes

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.33 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content