AVALIAÇÃO DA IMDb

7,1/10

12 mil

SUA AVALIAÇÃO

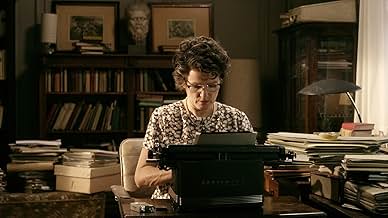

Um olhar sobre a vida da filósofa e teórica política Hannah Arendt, que relatou para The New Yorker sobre o julgamento do líder nazi Adolf Eichmann em Jerusalém.Um olhar sobre a vida da filósofa e teórica política Hannah Arendt, que relatou para The New Yorker sobre o julgamento do líder nazi Adolf Eichmann em Jerusalém.Um olhar sobre a vida da filósofa e teórica política Hannah Arendt, que relatou para The New Yorker sobre o julgamento do líder nazi Adolf Eichmann em Jerusalém.

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Artistas

- Prêmios

- 8 vitórias e 18 indicações no total

Leila Lallali

- Student Laureen

- (as Leila Schaus)

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Elenco e equipe completos

- Produção, bilheteria e muito mais no IMDbPro

Avaliações em destaque

Margarethe von Trotta's Hannah Arendt is a film about thinking. Moreover, it's in favour of it. It so values thinking that it offers some elegant speeches and debate, sans computer generated spectaculars.

Barbara Sukowa portrays the German Jewish philosopher during the period she covered the Adolf Eichmann trial in Israel for The New Yorker. The film confronts the controversy Arendt raised when (i) she redefined Eichmann not as a monster but as an ordinary nobody, exemplifying "the banality of evil," (ii) she reported that some Jews collaborated with the Nazis, resulting in more deaths than chaos would have caused, and (iii) she said she loves her friends but not any "people," in this case, the Jews. On all three counts she was condemned for abandoning her people. Today, at a remove from the heat of that moment, she was clearly correct on all counts. For more see www.yacowar.blogspot.com.

Not loving the Jews was not being anti-Semitic but refusing to emotionalize her consideration of the issues. Arendt was opposed to the blanket love of any group of people, not based on personal engagement, because such nationalist or other group identification precluded the thoughtful consideration of any issues around them. She most valued a rational, thoughtful approach that was not prejudged or proscribed by any -ism or convention. As for some Jews' collaboration, she simply reported facts that arose at the trial. (Indeed, Rudolf van den Berg's new film Suskind details precisely that collaboration.) Nor was that observation anti-Semitic, for the possibly well-intentioned collaboration in the face of horrid danger is a plausible response among any people. Arendt was pilloried for facing the facts and for rejecting myths. That's what historians are required to do and apparently what philosophers periodically have to remind them to do.

Barbara Sukowa portrays the German Jewish philosopher during the period she covered the Adolf Eichmann trial in Israel for The New Yorker. The film confronts the controversy Arendt raised when (i) she redefined Eichmann not as a monster but as an ordinary nobody, exemplifying "the banality of evil," (ii) she reported that some Jews collaborated with the Nazis, resulting in more deaths than chaos would have caused, and (iii) she said she loves her friends but not any "people," in this case, the Jews. On all three counts she was condemned for abandoning her people. Today, at a remove from the heat of that moment, she was clearly correct on all counts. For more see www.yacowar.blogspot.com.

Not loving the Jews was not being anti-Semitic but refusing to emotionalize her consideration of the issues. Arendt was opposed to the blanket love of any group of people, not based on personal engagement, because such nationalist or other group identification precluded the thoughtful consideration of any issues around them. She most valued a rational, thoughtful approach that was not prejudged or proscribed by any -ism or convention. As for some Jews' collaboration, she simply reported facts that arose at the trial. (Indeed, Rudolf van den Berg's new film Suskind details precisely that collaboration.) Nor was that observation anti-Semitic, for the possibly well-intentioned collaboration in the face of horrid danger is a plausible response among any people. Arendt was pilloried for facing the facts and for rejecting myths. That's what historians are required to do and apparently what philosophers periodically have to remind them to do.

An intense look at the trouble life of philosopher and political theorist Hannah Arendt , who reported for The New Yorker on the war crimes trial of the Nazi Adolf Eichmann . It deals with her American personal experiences , as in 1950 , Hanna (Barbara Sukowa) became a naturalized citizen of the United States along with her husband Heinrich Blucher (Axel Milberg) . Arendt served as a visiting scholar at the University of California, Berkeley, Princeton University, and Northwestern University. In the spring of 1959, she became the first woman lecturer at Princeton ; Arendt also taught at the University of Chicago , The New School in Manhattan and Yale University . Furthermore , in the movie appears some flashbacks about her relationship with Martin Heidegger (Klaus Pohl) . Hanna was was a German-American political theorist as well as a prestigious philosopher . Arendt's work deals with the nature of power, and the subjects of politics, direct democracy, authority, and totalitarianism.

This is a brooding and thought-provoking biographic drama about the notorious philosopher focusing mainly the Eichman trial . Stands out the wonderful acting by Barbara Sukowa who is terrific in the title role . Support cast is frankly excellent such as Axel Milberg as her husband Heinrich Blucher , Janet McTeer as the writer Mary McCarthy and Julia Jentsch as her helper , the latter also starred another good film about Nazism titled ¨Sophie Scholl¨ . The motion picture was well directed by Margarethe Von Trotta and it belongs a trilogy dealing with Nazism , formed by ¨Roxa Luxemburg¨ also starred by Barbara Sukowa and ¨Rosenstrasse¨or Street of roses .

The picture is based on real events about Hanna Arendt life ; Arendt's first major book was entitled, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), which traced the roots of Stalinist Communism and Nazism in both anti-Semitism and imperialism . In her reporting of the Eichmann trial for The New Yorker, which evolved into Eichmann in Jerusalem : A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963), she coined the phrase "the banality of evil" to describe Eichmann. She raised the question of whether evil is radical or simply a function of thoughtlessness, a tendency of ordinary people to obey orders and conform to mass opinion without a critical evaluation of the consequences of their actions and inaction.Arendt was sharply critical of the way the trial was conducted in Israel. She also was critical of the way that some Jewish leaders, notably M. C. Rumkowski, acted during the Holocaust. This caused a considerable controversy and even animosity toward Arendt in the Jewish community. Her friend Gershom Scholem, a major scholar of Jewish mysticism, broke off relations with her. Arendt was criticized by many Jewish public figures, who charged her with coldness and lack of sympathy for the victims of the Shoah/Holocaust. Due to this lingering criticism, her book has only recently been translated into Hebrew.

This is a brooding and thought-provoking biographic drama about the notorious philosopher focusing mainly the Eichman trial . Stands out the wonderful acting by Barbara Sukowa who is terrific in the title role . Support cast is frankly excellent such as Axel Milberg as her husband Heinrich Blucher , Janet McTeer as the writer Mary McCarthy and Julia Jentsch as her helper , the latter also starred another good film about Nazism titled ¨Sophie Scholl¨ . The motion picture was well directed by Margarethe Von Trotta and it belongs a trilogy dealing with Nazism , formed by ¨Roxa Luxemburg¨ also starred by Barbara Sukowa and ¨Rosenstrasse¨or Street of roses .

The picture is based on real events about Hanna Arendt life ; Arendt's first major book was entitled, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), which traced the roots of Stalinist Communism and Nazism in both anti-Semitism and imperialism . In her reporting of the Eichmann trial for The New Yorker, which evolved into Eichmann in Jerusalem : A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963), she coined the phrase "the banality of evil" to describe Eichmann. She raised the question of whether evil is radical or simply a function of thoughtlessness, a tendency of ordinary people to obey orders and conform to mass opinion without a critical evaluation of the consequences of their actions and inaction.Arendt was sharply critical of the way the trial was conducted in Israel. She also was critical of the way that some Jewish leaders, notably M. C. Rumkowski, acted during the Holocaust. This caused a considerable controversy and even animosity toward Arendt in the Jewish community. Her friend Gershom Scholem, a major scholar of Jewish mysticism, broke off relations with her. Arendt was criticized by many Jewish public figures, who charged her with coldness and lack of sympathy for the victims of the Shoah/Holocaust. Due to this lingering criticism, her book has only recently been translated into Hebrew.

The film "Hannah Arendt" depicts an intriguing and contradictory intellectual but avoids examining the political core of the famous controversy it recounts. Arendt stirred a furor with her 1963 writings on the Israeli government's trial in Jerusalem of the Nazi Adolf Eichmann. She characterized Eichmann, who had organized the transport of European Jews to the death camps, as a banal bureaucrat rather than a singular monster. She wrote that European Jewish leaders, too, were responsible, by administering submission to the Nazis when even futile resistance and chaos might have allowed more Jews to survive. The public attacks on Arendt are shown. She was pilloried, particularly by Jewish intellectuals, as an unfeeling Nazi sympathizer and self-hating Jew. The New School's move to fire her is also enacted.

But the film, which shows Arendt as shocked to learn that she has hurt the feelings of many Jews, including long-time friends, does not reveal that she had broken with the Zionist leaders in 1942 when they called for a Jewish state rather than the bi-national Palestine she supported. The Zionists opposed measures to rescue Jews from the Nazis other than those that herded them to Palestine. They claimed, however, that their takeover of Palestine was all about saving Jews from a unique evil -- a claim unchallenged by most liberals as well as the Stalinist left. Arendt's analysis hit the Zionists' guilty conscience and undermined the rationale for their nationalist project. The film ignores these crucial political elements, and presents Arendt's strong defender and friend only as novelist "Mary" without disclosing that Mary McCarthy was an anti-Stalinist and anti-Zionist who called Zionism the "Jewish final solution."

Director Margarethe von Trotta's failure to explore this relevant history leaves her film interesting but superficial when it could have been brave and timely. Arendt's famous topic, thoughtless compliance with evildoers in power, needs our attention today more than ever. Fifty years after the "Banality of Evil" controversy, U.S. liberals and progressives are blindly uncritical of a leader who spies on millions and remotely executes foreigners and citizens in the name of national security. A militarily mighty Zionist state is still free to massacre innocents, shielded by this unquestioned U.S. power and the old sacred cow that Israel is the only safe haven for Jews. Arendt might have had some juicy comments about the "banality of filmmaking."

Rita Freed

But the film, which shows Arendt as shocked to learn that she has hurt the feelings of many Jews, including long-time friends, does not reveal that she had broken with the Zionist leaders in 1942 when they called for a Jewish state rather than the bi-national Palestine she supported. The Zionists opposed measures to rescue Jews from the Nazis other than those that herded them to Palestine. They claimed, however, that their takeover of Palestine was all about saving Jews from a unique evil -- a claim unchallenged by most liberals as well as the Stalinist left. Arendt's analysis hit the Zionists' guilty conscience and undermined the rationale for their nationalist project. The film ignores these crucial political elements, and presents Arendt's strong defender and friend only as novelist "Mary" without disclosing that Mary McCarthy was an anti-Stalinist and anti-Zionist who called Zionism the "Jewish final solution."

Director Margarethe von Trotta's failure to explore this relevant history leaves her film interesting but superficial when it could have been brave and timely. Arendt's famous topic, thoughtless compliance with evildoers in power, needs our attention today more than ever. Fifty years after the "Banality of Evil" controversy, U.S. liberals and progressives are blindly uncritical of a leader who spies on millions and remotely executes foreigners and citizens in the name of national security. A militarily mighty Zionist state is still free to massacre innocents, shielded by this unquestioned U.S. power and the old sacred cow that Israel is the only safe haven for Jews. Arendt might have had some juicy comments about the "banality of filmmaking."

Rita Freed

I didn't know an awful lot about philosopher Hannah Arendt before I saw this movie. Now I know a lot more about her, and about the way she thinks. After seeing the film, I have even read some articles about her work.

If that's what director Margarethe von Trotta had in mind when making this film, she succeeded. Her film documents an important chapter in the story of Arendt's life: her articles about the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem, and the ensuing tsunami of negative reactions. The reason for those negative reactions was the way Arendt regarded Eichmann: not as a monster, but as a man 'incapable of thinking', a dimwit who just followed orders. This fitted her theory of 'the banality of evil': the worst kinds of evil are often the result of not thinking for oneself.

Veteran actress Barbara Sukowa portrays Arendt as a difficult and complex woman, who is a brilliant philosopher but also stubborn, arrogant and single-minded. In one scene, we see her lying on a couch, when the phone rings. On the other end of the line is her editor, who faces a deadline and asks if she is making progress with the articles. 'Of course I'm working hard, and it would be nice if I could continue working instead of chatting on the phone', she answers. After that, she returns to the couch, lies down and continues smoking her cigarette.

Sometimes it seems that Arendt is incapable of feeling, just as Eichmann is incapable of thinking. Even when her best friends turn away from her, she continues insulting them by telling them 'she doesn't love the Jewish people'. She means it in a philosophical way - you can't love a people the way you love individuals. But nevertheless, it comes across as cold-hearted and insensitive.

Arendt is clearly an interesting person. But that doesn't make 'Hannah Arendt' an interesting film. From a cinematographic point of view, the movie doesn't have much to offer. It's a rather straightforward account of this episode in Arendt's life. The only thing that adds a little depth to the film are the flashbacks of the romantic affair she had with her teacher, the famous philosopher Martin Heidegger, who sympathized with the Nazis. The film suggests that this affair influenced the way she regarded Nazis such as Eichmann, but doesn't make this explicit. In my view, the film is interesting as a history lesson about this remarkable woman, but not as a great cinematographic experience.

If that's what director Margarethe von Trotta had in mind when making this film, she succeeded. Her film documents an important chapter in the story of Arendt's life: her articles about the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem, and the ensuing tsunami of negative reactions. The reason for those negative reactions was the way Arendt regarded Eichmann: not as a monster, but as a man 'incapable of thinking', a dimwit who just followed orders. This fitted her theory of 'the banality of evil': the worst kinds of evil are often the result of not thinking for oneself.

Veteran actress Barbara Sukowa portrays Arendt as a difficult and complex woman, who is a brilliant philosopher but also stubborn, arrogant and single-minded. In one scene, we see her lying on a couch, when the phone rings. On the other end of the line is her editor, who faces a deadline and asks if she is making progress with the articles. 'Of course I'm working hard, and it would be nice if I could continue working instead of chatting on the phone', she answers. After that, she returns to the couch, lies down and continues smoking her cigarette.

Sometimes it seems that Arendt is incapable of feeling, just as Eichmann is incapable of thinking. Even when her best friends turn away from her, she continues insulting them by telling them 'she doesn't love the Jewish people'. She means it in a philosophical way - you can't love a people the way you love individuals. But nevertheless, it comes across as cold-hearted and insensitive.

Arendt is clearly an interesting person. But that doesn't make 'Hannah Arendt' an interesting film. From a cinematographic point of view, the movie doesn't have much to offer. It's a rather straightforward account of this episode in Arendt's life. The only thing that adds a little depth to the film are the flashbacks of the romantic affair she had with her teacher, the famous philosopher Martin Heidegger, who sympathized with the Nazis. The film suggests that this affair influenced the way she regarded Nazis such as Eichmann, but doesn't make this explicit. In my view, the film is interesting as a history lesson about this remarkable woman, but not as a great cinematographic experience.

Folks, this is what Philosophy is all about: taking a stand which is not always popular and being able to justify it for the ages. Hannah Arendt is only in this century beginning to receive her due as the most perspicuous political philosopher of the 20th century. After all, it was Ms Arendt who first observed that post-Hiroshima, a conventional war could never again be fought and won. But rather, all pre-emptive invasions who devolve into occupations - that rather than full-scale war or revolutions - the world would sink increasingly into a mire of entropic violence. Her controversial thesis in Eichmann In Jerusalem - yet another masterpiece of at least five in her canon, is that mass atrocities are not committed by idiosyncratic madmen who erect vast engines of evil in which the followers (citizens of the state) serve as the 'cogs' – but rather the architectonic of evil consists in the actions of rather ordinary people who for various reasons and rationalizations refuse to think about the ramifications of what they're doing. I mention this point because I've studied Ms Arendt's work for over three decades, lived in Greenwich Village when she was teaching at the New School, and when I saw the film premiere at the Santa Barbara Film Festival this past January – I felt that most of the scant audience did not get the point any more than her contemporaries. The film-making is excellent. To dramatize philosophic ideas is challenge in itself. Von Trotta, in the old European style, makes her films with a regular group of actors, and, while the performances were effective throughout, in real life, Hannah Arendt was not nearly so physically engaging and Mary McCarthy quite a bit more – which, I believe had something to do with the development their respective moral characters. All in all, a great, not merely a good, film – and one of the few worth seeing thus far this year – unless, of course, the attributes of fast and furious 6 or iron man 3 overwhelm.

Você sabia?

- CuriosidadesFor a deeper understanding of this story, one might care to watch Operação Final (2018), which depicts the undercover mission to find and extract Adolf Eichmann from Argentina and bring him to trial in Israel. Showing the background of an operation sanctioned by PM David Ben-Gurion, the film gives a glimpse of the complexity of Eichman's character, his futile attempts to justify his actions and tell his side of the story.

- Erros de gravaçãoWhen Arendt stands on the terrace of her hotel in Jerusalem at looks across the Valley of Hinnom at the Old City, there are Israel flags flying from the Tower of David complex. However, the Old City of Jerusalem was still under Jordanian control in 1961.

- Citações

Hannah Arendt: You describe a book I never wrote.

Siegfried Moses: A book that will never be allowed in Israel. And won't appear anywhere else either if you have any decency left.

Hannah Arendt: You ban books, and lecture me about decency!

- ConexõesFeatured in Kino Kino: Hannah Arendt (2013)

Principais escolhas

Faça login para avaliar e ver a lista de recomendações personalizadas

- How long is Hannah Arendt?Fornecido pela Alexa

Detalhes

- Data de lançamento

- Países de origem

- Central de atendimento oficial

- Idiomas

- Também conhecido como

- Hannah Arendt

- Locações de filme

- Empresas de produção

- Consulte mais créditos da empresa na IMDbPro

Bilheteria

- Faturamento bruto nos EUA e Canadá

- US$ 717.205

- Fim de semana de estreia nos EUA e Canadá

- US$ 31.270

- 2 de jun. de 2013

- Faturamento bruto mundial

- US$ 8.880.936

- Tempo de duração

- 1 h 53 min(113 min)

- Cor

- Mixagem de som

- Proporção

- 2.35 : 1

Contribua para esta página

Sugerir uma alteração ou adicionar conteúdo ausente