AVALIAÇÃO DA IMDb

6,8/10

5,3 mil

SUA AVALIAÇÃO

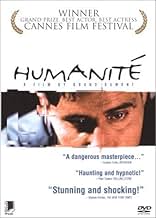

Cuando una niña de 11 años es violada y asesinada en un tranquilo pueblo francés, un detective que ha olvidado cómo sentir las emociones, debido a la muerte de su propia familia en algún tip... Ler tudoCuando una niña de 11 años es violada y asesinada en un tranquilo pueblo francés, un detective que ha olvidado cómo sentir las emociones, debido a la muerte de su propia familia en algún tipo de accidente, investiga el crimen.Cuando una niña de 11 años es violada y asesinada en un tranquilo pueblo francés, un detective que ha olvidado cómo sentir las emociones, debido a la muerte de su propia familia en algún tipo de accidente, investiga el crimen.

- Prêmios

- 3 vitórias e 3 indicações no total

Darius

- L'infirmier

- (as Daniel Leroux)

Robert Bunzi

- Le policier anglais

- (as Robert Bunzl)

Avaliações em destaque

"The power of cinema lies in the return of man to the body, to the heart, to truth" - Bruno Dumont

In L'Humanite, by Bruno Dumont (La Vie de Jesus), Pharaon de Winter (Emmanuel Schotte) is a Police Superintendent called upon to investigate the murder and rape of an 11-year old girl. Flaunting almost every cinematic convention, the film is not about solving a crime but a 2 1/2-hour poem of mood, time, silence and spirit. Set in northern France in the director's hometown of Bailleul, the characters are unglamorous members of the working class. Dumont devotes long stretches of the film to simply observing Pharaon going about his life: eating an apple, tending his garden, watching a soccer game on television, interacting with his mother, or being a friend to his neighbor Domino (Severine Caneele), a rugged factory worker and her obnoxious bus-driver boyfriend Joseph (Philippe Tullier). He is an unlikely cop, a passive, stoop-shouldered, and empathetic man who would sooner kiss a prisoner on the lips or stroke his neck as browbeat him. Pharaon sees the suffering of the world and wants to hold it in his hands and stroke it. Schotte's performance is so expressive that his best actor award at Cannes was criticized because most people thought he wasn't acting, just being himself.

As the film opens, a man is walking in the distance alone across a grassy hill. Suddenly as the camera moves in for a close-up, he collapses in the mud and just lays there for a while. Is he dead or alive? Did he commit the crime? In the next scene, he is sitting in his car listening to harpsichord music and we discover that he is a policeman talking in a barely audible voice to his superior. The film cuts away to the battered body of an 11-year old girl, her torn and bloody vagina graphically shown as the police gather. Pharaon maintains the same anguished, enigmatic look on his face throughout that makes us uncertain if he is the murderer or the Second Coming of Christ. We know very little about him except that he "lost" his wife and child a few years ago, but it is never made clear whether he lost them or they lost him. Signs of passion or involvement are rare but come with a sudden ferocity, as when he is walking across the crime scene and starts to scream at the top of his lungs, a sound drowned out only by the passing Eurostar train.

L'Humanite is an involving and disturbing film that you cannot feel lukewarm about. It is profoundly moving but often agonizingly slow and virtually unwatchable in some of its graphic details (you may never want to have sex again after watching these mechanical exercises). The climax of the film is as perplexing as the beginning with an ambiguous resolution that I'm not quite sure what to make of. What I do know is that I felt as vitally alive watching this film as I did the first time that I saw Leolo by Jean-Claude Lauzon. L'Humanite is a breath of fresh air on the turgid cinema landscape and Dumont is as honest and challenging a director as I've seen in quite a long time. His film continually forces us to question what we are looking at and, as the title suggests, keeps bringing us closer and closer to the core of what makes us truly human.

In L'Humanite, by Bruno Dumont (La Vie de Jesus), Pharaon de Winter (Emmanuel Schotte) is a Police Superintendent called upon to investigate the murder and rape of an 11-year old girl. Flaunting almost every cinematic convention, the film is not about solving a crime but a 2 1/2-hour poem of mood, time, silence and spirit. Set in northern France in the director's hometown of Bailleul, the characters are unglamorous members of the working class. Dumont devotes long stretches of the film to simply observing Pharaon going about his life: eating an apple, tending his garden, watching a soccer game on television, interacting with his mother, or being a friend to his neighbor Domino (Severine Caneele), a rugged factory worker and her obnoxious bus-driver boyfriend Joseph (Philippe Tullier). He is an unlikely cop, a passive, stoop-shouldered, and empathetic man who would sooner kiss a prisoner on the lips or stroke his neck as browbeat him. Pharaon sees the suffering of the world and wants to hold it in his hands and stroke it. Schotte's performance is so expressive that his best actor award at Cannes was criticized because most people thought he wasn't acting, just being himself.

As the film opens, a man is walking in the distance alone across a grassy hill. Suddenly as the camera moves in for a close-up, he collapses in the mud and just lays there for a while. Is he dead or alive? Did he commit the crime? In the next scene, he is sitting in his car listening to harpsichord music and we discover that he is a policeman talking in a barely audible voice to his superior. The film cuts away to the battered body of an 11-year old girl, her torn and bloody vagina graphically shown as the police gather. Pharaon maintains the same anguished, enigmatic look on his face throughout that makes us uncertain if he is the murderer or the Second Coming of Christ. We know very little about him except that he "lost" his wife and child a few years ago, but it is never made clear whether he lost them or they lost him. Signs of passion or involvement are rare but come with a sudden ferocity, as when he is walking across the crime scene and starts to scream at the top of his lungs, a sound drowned out only by the passing Eurostar train.

L'Humanite is an involving and disturbing film that you cannot feel lukewarm about. It is profoundly moving but often agonizingly slow and virtually unwatchable in some of its graphic details (you may never want to have sex again after watching these mechanical exercises). The climax of the film is as perplexing as the beginning with an ambiguous resolution that I'm not quite sure what to make of. What I do know is that I felt as vitally alive watching this film as I did the first time that I saw Leolo by Jean-Claude Lauzon. L'Humanite is a breath of fresh air on the turgid cinema landscape and Dumont is as honest and challenging a director as I've seen in quite a long time. His film continually forces us to question what we are looking at and, as the title suggests, keeps bringing us closer and closer to the core of what makes us truly human.

This film has been praised as shocking, fascinating, and hypnotic; and I can only conclude that I'm not easily shocked, fascinated, or hypnotized. I was lulled to sleep several times, and watched the film over the course of several days. The film is quite sedately paced. An example:

You get a shot of Pharoan looking at his boss's collar. The shot of the collar holds long enough for you to think "Hm, he sweats a lot." The shot holds long enough for you to think "okay, I got that, thanks. He sweats a lot." Then it holds long enough for you to think "All right already! Go wake up the editor."

A sequence like that would not be a problem when the cinematography is particularly good, except the cinematography in this film is not. It is competent, straightforward, unstylized, perhaps even dull; in other words, the cinematography serves the story perfectly.

The sedate pacing might not be a problem with different cinematography, which would affect the story for the better: the film is a psychological exploration, yet the people we're meant to sympathize with are typically shown in long shots or in closeup but with largely unchanging expressions. If something is going on behind the eyes, we can only guess what it is; and from the slack-jawed expression, we guess that what it is might not even be particularly profound. Wounded, yes, sad, yes, but we've seen that before and better, and it's nothing new. We need a reason to care *this time*, and for many people that reason won't be there.

The main character is a cipher, perhaps deliberately so, but the result is a film that doesn't tell you anything, and doesn't even tell you why it doesn't tell you anything--not the nihilism or the weary practicality of some noir films, but merely a bloated anecdote with an obscure or missing point. Unfortunately the anecdote, aside from being quite slow, is also almost completely humorless. The result is a film only for people with extraordinary patience and good will.

You get a shot of Pharoan looking at his boss's collar. The shot of the collar holds long enough for you to think "Hm, he sweats a lot." The shot holds long enough for you to think "okay, I got that, thanks. He sweats a lot." Then it holds long enough for you to think "All right already! Go wake up the editor."

A sequence like that would not be a problem when the cinematography is particularly good, except the cinematography in this film is not. It is competent, straightforward, unstylized, perhaps even dull; in other words, the cinematography serves the story perfectly.

The sedate pacing might not be a problem with different cinematography, which would affect the story for the better: the film is a psychological exploration, yet the people we're meant to sympathize with are typically shown in long shots or in closeup but with largely unchanging expressions. If something is going on behind the eyes, we can only guess what it is; and from the slack-jawed expression, we guess that what it is might not even be particularly profound. Wounded, yes, sad, yes, but we've seen that before and better, and it's nothing new. We need a reason to care *this time*, and for many people that reason won't be there.

The main character is a cipher, perhaps deliberately so, but the result is a film that doesn't tell you anything, and doesn't even tell you why it doesn't tell you anything--not the nihilism or the weary practicality of some noir films, but merely a bloated anecdote with an obscure or missing point. Unfortunately the anecdote, aside from being quite slow, is also almost completely humorless. The result is a film only for people with extraordinary patience and good will.

In this case, largely one man's reality, although several others are involved. I hesitate to make literary comparisons, because film is a visual medium with its own immediacy, but the central characters of the novels by Emmanuel Bove and Patrick Susskind ("The Pigeon" in particular) put me very much in mind of Pharaon de Winter, the "hero" of this film and is one reason I love it. The inwardness,the soulful need that is barely understood by the man himself, the sometimes interminably slow pace bring a profound melancholic tone that I have rarely experienced on the screen.

I agree with others who've posted here, this isn't a film for everyone. But if you are moved by the deep existential reflection and quiet, sensitive behavior of a person who can empathize out of his/her own pain, I would recommend this movie.

I agree with others who've posted here, this isn't a film for everyone. But if you are moved by the deep existential reflection and quiet, sensitive behavior of a person who can empathize out of his/her own pain, I would recommend this movie.

The French writer-director Bruno Dumont achieves something rarely accomplished since TAXI DRIVER and ERASERHEAD: a way of looking at the world entirely afresh. Unlike those movies--or the recent, Expressionist CLEAN, SHAVEN--Dumont doesn't distort the physical world, make it elastic or dreamlike. But he somehow makes us feel the world is being recorded by a very wise child from another planet. Everything, absolutely everything, from human behavior to wind rippling over a field of grass, is seen as never before. Ezra Pound's injunction to "make it new" is stamped on every frame.

Pharaon is a slow-witted police superintendent who is anything but pharaonic. He had a girlfriend and a baby, now dead. (We are not told how.) He is friends with Domino, a big-boned, sensitive, slatternly woman next door, and Joseph, her handsome beau, with whom she seems to never stop having sex. In their small town, a little girl has been raped and murdered. Pharaon pursues this case, as he pursues a sort of inarticulate love for Domino. Along the way, a light dawns in Pharaon--a dreadful light. He becomes sensitive to the suffering of all living things--a pig hurt by the suckling of her young, all the way to a motorist getting a beating outside police headquarters. The effect this has is to create a kind of moral schizophrenia in Pharaon: he can filter out nothing. Like an overlap of Raskolnikov and Prince Mishkin, Pharaon takes both the world's sin and sufferings on his back.

But this gives only the barest outline of the experience of L'HUMANITE, which is not about its plot. Indeed, the relationship of Dumont's handling of the materials of cinema to the story itself is unique in my experience of narrative moviemaking. Like Abbas Kiarostami in his recent work, Dumont uses the landscape not to illustrate the story, but to propose a dialectic against it. Where the landscape acts as an argument for life in Kiarostami's TASTE OF CHERRY, here it does something else. It vibrates with feeling. In its childlike gaze at the hardness of people and things, L'HUMANITE tries to get at the shifting feelings underneath--the emotions and sensations so elusive there are no words for them. The movie proves that literary means--finding names--are unnecessary. Dumont finds aural-visual-rhythmic means to voice those emotions.

His techniques can be daring, appalling. Pharaon, gradually overwhelmed by the world's thousand and one cruelties, starts to spontaneously embrace (relative) total strangers, in scenes one can imagine giving audiences giggles. Dumont doesn't care.

L'HUMANITE is the kind of movie that, while you're watching it, you feel can drive you crazy in places, but which you know you'll live with and re-play in your head for the rest of your life. And Cannes naysayers to the contrary, all the performances in this movie--all of them, down to the tiniest--are perfect.

A note: I would like to thank the other people who wrote about L'HUMANITE on IMDB. With no other movie have I felt I learned so much by reading other people's responses, and particularly noting the details they chose to underline. For the authenticity and unabashedness of everyone's responses, I am truly grateful.

Pharaon is a slow-witted police superintendent who is anything but pharaonic. He had a girlfriend and a baby, now dead. (We are not told how.) He is friends with Domino, a big-boned, sensitive, slatternly woman next door, and Joseph, her handsome beau, with whom she seems to never stop having sex. In their small town, a little girl has been raped and murdered. Pharaon pursues this case, as he pursues a sort of inarticulate love for Domino. Along the way, a light dawns in Pharaon--a dreadful light. He becomes sensitive to the suffering of all living things--a pig hurt by the suckling of her young, all the way to a motorist getting a beating outside police headquarters. The effect this has is to create a kind of moral schizophrenia in Pharaon: he can filter out nothing. Like an overlap of Raskolnikov and Prince Mishkin, Pharaon takes both the world's sin and sufferings on his back.

But this gives only the barest outline of the experience of L'HUMANITE, which is not about its plot. Indeed, the relationship of Dumont's handling of the materials of cinema to the story itself is unique in my experience of narrative moviemaking. Like Abbas Kiarostami in his recent work, Dumont uses the landscape not to illustrate the story, but to propose a dialectic against it. Where the landscape acts as an argument for life in Kiarostami's TASTE OF CHERRY, here it does something else. It vibrates with feeling. In its childlike gaze at the hardness of people and things, L'HUMANITE tries to get at the shifting feelings underneath--the emotions and sensations so elusive there are no words for them. The movie proves that literary means--finding names--are unnecessary. Dumont finds aural-visual-rhythmic means to voice those emotions.

His techniques can be daring, appalling. Pharaon, gradually overwhelmed by the world's thousand and one cruelties, starts to spontaneously embrace (relative) total strangers, in scenes one can imagine giving audiences giggles. Dumont doesn't care.

L'HUMANITE is the kind of movie that, while you're watching it, you feel can drive you crazy in places, but which you know you'll live with and re-play in your head for the rest of your life. And Cannes naysayers to the contrary, all the performances in this movie--all of them, down to the tiniest--are perfect.

A note: I would like to thank the other people who wrote about L'HUMANITE on IMDB. With no other movie have I felt I learned so much by reading other people's responses, and particularly noting the details they chose to underline. For the authenticity and unabashedness of everyone's responses, I am truly grateful.

This French oddity from second-time director Bruno Dumont is a masterpiece. Four minutes into the film I was ready to switch it off, but once I'd settled into the rhythm of the film I was transfixed. That took about 20 minutes, and once I'd finished the film I re-watched those first 20 minutes again.

A policeman investigates the brutal murder of a young girl in a French town and that's pretty much it. It's even less than that in some respects. For example the girl is found in the opening minutes, but it's 50 minutes before any real investigation begins. Instead it focuses on the policeman (Pharaon) and his two friends (lovers Domino and Joseph). They go to the beach, to a restaurant, stand outside their houses having stunted conversations and generally wasting the day away. Pharaon goes for a bicycle ride and tends to his allotment. Essentially nothing happens. There are maybe four or five actual plot points altogether, and the rest is filled with chat of the "Hi, how are you?" variety, long shots of people walking or driving, or opening doors. The entire film follows a kind of rhythmic cycle that becomes hypnotic if you allow it.

Which brings us to the actors. The DVD notes say they're all non-professionals. Not amateur actors, but real people who are acting for the first time. The actor who plays Joseph does reasonably well, but Domino is excellent (and it's an extremely brave performance for any actress).

Emmanuel Schotte (as Pharaon) is amazing. It's simply one of the greatest performances I've ever seen. Imagine Travis Bickle with 99pc of the anger taken out. Then cross him with Forrest Gump (with non of Hanks' caricature or comedy). Cast a non-actor who looks like a cross between Clive Owen and Alfred Molina and you're somewhere close. He's a very unlikely cop. He's wide-eyed, innocent, and simple. He's slow and deliberate. Brief comments from other characters tell us his wife and child died two years ago, and he looks like a man still stunned, as if he'd just heard the news. This is never hinted at once; we don't ever see what he was like before, no one ever tells him "You've changed", but the audience gets the feeling this is a man suffering desperately from the pain of grief. Most of this is expressed in Schotte's eyes which are desperately sad.

This low-key little film requires patience. Without Schotte's performance I don't think there'd be much of a film here. Be prepared for an extremely slow film, but one that's never boring. It will polarise opinion like few other films I've seen so I can't recommend it to everyone (and there are some very graphic sex scenes), but I thought it was amazing.

A policeman investigates the brutal murder of a young girl in a French town and that's pretty much it. It's even less than that in some respects. For example the girl is found in the opening minutes, but it's 50 minutes before any real investigation begins. Instead it focuses on the policeman (Pharaon) and his two friends (lovers Domino and Joseph). They go to the beach, to a restaurant, stand outside their houses having stunted conversations and generally wasting the day away. Pharaon goes for a bicycle ride and tends to his allotment. Essentially nothing happens. There are maybe four or five actual plot points altogether, and the rest is filled with chat of the "Hi, how are you?" variety, long shots of people walking or driving, or opening doors. The entire film follows a kind of rhythmic cycle that becomes hypnotic if you allow it.

Which brings us to the actors. The DVD notes say they're all non-professionals. Not amateur actors, but real people who are acting for the first time. The actor who plays Joseph does reasonably well, but Domino is excellent (and it's an extremely brave performance for any actress).

Emmanuel Schotte (as Pharaon) is amazing. It's simply one of the greatest performances I've ever seen. Imagine Travis Bickle with 99pc of the anger taken out. Then cross him with Forrest Gump (with non of Hanks' caricature or comedy). Cast a non-actor who looks like a cross between Clive Owen and Alfred Molina and you're somewhere close. He's a very unlikely cop. He's wide-eyed, innocent, and simple. He's slow and deliberate. Brief comments from other characters tell us his wife and child died two years ago, and he looks like a man still stunned, as if he'd just heard the news. This is never hinted at once; we don't ever see what he was like before, no one ever tells him "You've changed", but the audience gets the feeling this is a man suffering desperately from the pain of grief. Most of this is expressed in Schotte's eyes which are desperately sad.

This low-key little film requires patience. Without Schotte's performance I don't think there'd be much of a film here. Be prepared for an extremely slow film, but one that's never boring. It will polarise opinion like few other films I've seen so I can't recommend it to everyone (and there are some very graphic sex scenes), but I thought it was amazing.

Você sabia?

- CuriosidadesThe body of the raped little girl was a silicone cast.

- Citações

[first lines]

l'inspecteur de police Pharaon De Winter: I'm coming.

- Versões alternativasItalian distributor BIM originally removed about 2 minutes of sex footage from the Italian theatrical release in order to avoid a 'not under 18' rating. When the press criticized this self-censorship attempt, the distributor reissued the film in its original, integral form.

- Trilhas sonorasLe Vertigo, Rondeau. Modérément

from "Pièce de Clavecin"

Music by Pancrace Royer

Performed by William Christie

Courtesy of harmonia mundi

Principais escolhas

Faça login para avaliar e ver a lista de recomendações personalizadas

- How long is Humanité?Fornecido pela Alexa

Detalhes

- Data de lançamento

- País de origem

- Centrais de atendimento oficiais

- Idiomas

- Também conhecido como

- Humanity

- Locações de filme

- Bailleul, Nord, França(Village)

- Empresas de produção

- Consulte mais créditos da empresa na IMDbPro

Bilheteria

- Faturamento bruto nos EUA e Canadá

- US$ 113.495

- Fim de semana de estreia nos EUA e Canadá

- US$ 10.075

- 18 de jun. de 2000

- Tempo de duração2 horas 21 minutos

- Cor

- Mixagem de som

- Proporção

- 2.35 : 1

Contribua para esta página

Sugerir uma alteração ou adicionar conteúdo ausente