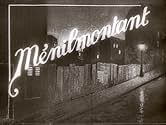

Ménilmontant

- 1926

- 38 min

AVALIAÇÃO DA IMDb

7,8/10

2,9 mil

SUA AVALIAÇÃO

Adicionar um enredo no seu idiomaA couple is brutally murdered in the working-class district of Paris. Later on, the narrative follows the lives of their two daughters, both in love with a Parisian thug and leading them to ... Ler tudoA couple is brutally murdered in the working-class district of Paris. Later on, the narrative follows the lives of their two daughters, both in love with a Parisian thug and leading them to separate ways.A couple is brutally murdered in the working-class district of Paris. Later on, the narrative follows the lives of their two daughters, both in love with a Parisian thug and leading them to separate ways.

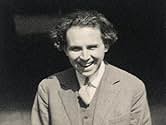

- Direção

- Roteirista

- Artistas

Avaliações em destaque

The Ménilmontant depicted here by Dimitri Kirsanofff is a far cry from the picturesque village of Charles Trenet's famous chanson. The grim and narrow cobbled streets provide a backdrop for a film of which the subject matter is that of conventional melodrama but which has been raised by Dimitri Kirsanoff to the level of cinematic art.

The stylistic effects he employs are those of Impressionism, notably rapid montage, superimposition and flashbacks but never at the expense of the narrative and nigh-on a century later the film's emotive power has not diminished and remains a devastating piece of social realism which concerns two orphaned sisters who are eventually reconciled, having been betrayed by the same man.

Suffice to say the lynchpin is the director's wife and muse Nadia Sibirskaia whose face is adored by the camera and whose performance as the younger sister is stunning in its simplicity.

The mood of the film is heightened by the newly composed score of the talented Paul Mercer.

This is the second and indeed oldest surviving film of Russian émigré Kirsanoff and although to my knowledge he never again reached such heights this piece of ciné poetry guarantees his immortality.

The stylistic effects he employs are those of Impressionism, notably rapid montage, superimposition and flashbacks but never at the expense of the narrative and nigh-on a century later the film's emotive power has not diminished and remains a devastating piece of social realism which concerns two orphaned sisters who are eventually reconciled, having been betrayed by the same man.

Suffice to say the lynchpin is the director's wife and muse Nadia Sibirskaia whose face is adored by the camera and whose performance as the younger sister is stunning in its simplicity.

The mood of the film is heightened by the newly composed score of the talented Paul Mercer.

This is the second and indeed oldest surviving film of Russian émigré Kirsanoff and although to my knowledge he never again reached such heights this piece of ciné poetry guarantees his immortality.

Menilmontant (1926) was, in the modest context of the alternative cinema circuit, a smash hit. It's great success allowed filmmaker Dimitri Kirsanov to go on making films, and also helped Jean Tedesco to stay in business as an exhibitor.

Like Kirsanov's first film, Menilmontant (again starring Kirsanoff's first wife, the beautiful Nadia Sibirskaia) tells a story without the use of inter-titles. It is often said that the filmmakers cinema is poetic, but one must add that in his second film he explored the poetics of violence and degradation.

The story begins and ends with two unrelated, but similarly filmed and edited murders. In each case, the grisly event does not grow organically out of the plot, but seems to surge out of a world welling with violent impulses.

Menilmontant uses practically all of the typical stylistic devices of cinematic impressionism, but it is hard to consider it as in any way representative of the movement. It's overwhelming, virtually unrelieved violence and despair seem to infect its own storytelling agency, upsetting what in other filmmakers' works would be clearly delineated relations of parts to the whole.

The film contains several bursts of rapid editing, for example, but they are not rhythmic in any simple, narratively justified way (in the manner of Abel Gance, for example); their meter is complicated and unsettling, worthy of an Igor Stravinsky. The film offers several notable examples of subjective camera work, but typically these become slightly unhinged, with no absolute certainty as to which character's experience in being rendered.

Menilmontant is, quite deliberately, a film in which the formal center cannot hold, because it is about a world in which this is also true. Although certainly not a Surrealist work, it shares with Surrealism no only a fascination with violence and sexuality, but also a display of forces and transcend, and question the boundaries of, individual human consciousness.

Kirsanov concluded his Menilmontant with a shot of impoverished and exploited young women fashioning artificial flowers in the poorest district of Paris, he provided us the most comprehensive image, aesthetic and social, of this form of cinema. Through a panoply of stylistic experiments and through glorious close-ups of the incomparably fragile face of Sibirskaia, Kirsanov thought he had shaped a harsh milieu into an exquisite flower. But a flower for whom? Menilmontant would become a major film on the cine-club and specialized cinema circuit, but never played to the people of the working class quatier that gave it its title. This was not Kirsanov's public anyway, for he came from the Russian aristocracy. In 1919, having fled the Revolution, he was reduced to playing his beloved cello in movie houses just to be able to eat. He must have been tempted to imagine himself and his music as an unappreciated flower in the crude milieu of mass art.

Seen this way, Menilmontant becomes a personal triumph of art over industry, of the icon of Sibirskaia over the brutal world of plot and spectacle that constitutes ordinary cinema. That triumph is signaled in the miracle of the film's narration, the first French film without titles, a tale told completely through the eloquence of its images. The dark alleys of the nineteenth arrondissment, the streetlights listening on the Seine, and the pathetic decor of shabby apartments are all redeemed by art. No silent film more clearly bewails the fate of art in our century, more obviously appeals to connoisseurs of the emotions roused by artificial flowers.

Like Kirsanov's first film, Menilmontant (again starring Kirsanoff's first wife, the beautiful Nadia Sibirskaia) tells a story without the use of inter-titles. It is often said that the filmmakers cinema is poetic, but one must add that in his second film he explored the poetics of violence and degradation.

The story begins and ends with two unrelated, but similarly filmed and edited murders. In each case, the grisly event does not grow organically out of the plot, but seems to surge out of a world welling with violent impulses.

Menilmontant uses practically all of the typical stylistic devices of cinematic impressionism, but it is hard to consider it as in any way representative of the movement. It's overwhelming, virtually unrelieved violence and despair seem to infect its own storytelling agency, upsetting what in other filmmakers' works would be clearly delineated relations of parts to the whole.

The film contains several bursts of rapid editing, for example, but they are not rhythmic in any simple, narratively justified way (in the manner of Abel Gance, for example); their meter is complicated and unsettling, worthy of an Igor Stravinsky. The film offers several notable examples of subjective camera work, but typically these become slightly unhinged, with no absolute certainty as to which character's experience in being rendered.

Menilmontant is, quite deliberately, a film in which the formal center cannot hold, because it is about a world in which this is also true. Although certainly not a Surrealist work, it shares with Surrealism no only a fascination with violence and sexuality, but also a display of forces and transcend, and question the boundaries of, individual human consciousness.

Kirsanov concluded his Menilmontant with a shot of impoverished and exploited young women fashioning artificial flowers in the poorest district of Paris, he provided us the most comprehensive image, aesthetic and social, of this form of cinema. Through a panoply of stylistic experiments and through glorious close-ups of the incomparably fragile face of Sibirskaia, Kirsanov thought he had shaped a harsh milieu into an exquisite flower. But a flower for whom? Menilmontant would become a major film on the cine-club and specialized cinema circuit, but never played to the people of the working class quatier that gave it its title. This was not Kirsanov's public anyway, for he came from the Russian aristocracy. In 1919, having fled the Revolution, he was reduced to playing his beloved cello in movie houses just to be able to eat. He must have been tempted to imagine himself and his music as an unappreciated flower in the crude milieu of mass art.

Seen this way, Menilmontant becomes a personal triumph of art over industry, of the icon of Sibirskaia over the brutal world of plot and spectacle that constitutes ordinary cinema. That triumph is signaled in the miracle of the film's narration, the first French film without titles, a tale told completely through the eloquence of its images. The dark alleys of the nineteenth arrondissment, the streetlights listening on the Seine, and the pathetic decor of shabby apartments are all redeemed by art. No silent film more clearly bewails the fate of art in our century, more obviously appeals to connoisseurs of the emotions roused by artificial flowers.

10sandover

Poverty, disillusion, and yet grace graces the screen when Nadia Sibirskaya nods to the old man who offers her some food to chew. That scene, that means her social grace, brought me tears and elated me at once - miracles, oh yes, do and do happen and move.

One should note that the old man does not reciprocate, in fact does not look at her at all, and this marks Kirsanoff's extraordinary finesse: if there was some kind of "communication" between the two, THIS would be melodramatic; for I do not think this film is a melodrama, at least the way we have come to mean one. To deny that the story is something that could have "happened", is to deny the film's class and émigré conscience.

On the other hand I am not sure I would claim, as another reviewer did, that this is Zola-like; we would then be a bit far from "Menilmontant"'s drastic, dislocated lyricism.

Watch the cutting close-ups the two times Sibirskaya's eloquent face witnesses a violent scene: the camera, a bit dislocated each time, and unafraid to jump and shut transitive seconds.

Watch the scene where she strongly contemplates something and starts descending the steps to the river: there is a sense of menace and imminent loss, I am not sure I ever witnessed before in a film: this is film-making on the heights; as is the camera work which frames hesitant feet on the steps, and hushes astonishingly their turning round.

Watch the protagonist's face after she arguably loses her virginity: inscrutable and fascinating, not allowing us truly tell if the vision of her wandering in the woods is one of innocence lost or burgeoning sexuality. But there is, that is a visceral sense of feminine enjoyment, perhaps close to a Balthus painting mood.

At the end one is left with a sense of bifurcation: with sisters reconciled, we are left with a confusing and not redeeming crime. We don't know who or why exactly and if the girl involves herself out of vengeance, private reasons or what you will; that makes it all the more unsavory and artistically right.

Then the camera looks disjointedly up into the Parisian sky, and hands resume their work of artificial bouquets; yes, the film seems to suggest, this is all what one is left with, artificial bouquets and handiwork.

Two sisters, two deflorations, two crimes, twice the work of flowers: the work of the two Kirsanoffs genial, amazing sensibilities.

One should note that the old man does not reciprocate, in fact does not look at her at all, and this marks Kirsanoff's extraordinary finesse: if there was some kind of "communication" between the two, THIS would be melodramatic; for I do not think this film is a melodrama, at least the way we have come to mean one. To deny that the story is something that could have "happened", is to deny the film's class and émigré conscience.

On the other hand I am not sure I would claim, as another reviewer did, that this is Zola-like; we would then be a bit far from "Menilmontant"'s drastic, dislocated lyricism.

Watch the cutting close-ups the two times Sibirskaya's eloquent face witnesses a violent scene: the camera, a bit dislocated each time, and unafraid to jump and shut transitive seconds.

Watch the scene where she strongly contemplates something and starts descending the steps to the river: there is a sense of menace and imminent loss, I am not sure I ever witnessed before in a film: this is film-making on the heights; as is the camera work which frames hesitant feet on the steps, and hushes astonishingly their turning round.

Watch the protagonist's face after she arguably loses her virginity: inscrutable and fascinating, not allowing us truly tell if the vision of her wandering in the woods is one of innocence lost or burgeoning sexuality. But there is, that is a visceral sense of feminine enjoyment, perhaps close to a Balthus painting mood.

At the end one is left with a sense of bifurcation: with sisters reconciled, we are left with a confusing and not redeeming crime. We don't know who or why exactly and if the girl involves herself out of vengeance, private reasons or what you will; that makes it all the more unsavory and artistically right.

Then the camera looks disjointedly up into the Parisian sky, and hands resume their work of artificial bouquets; yes, the film seems to suggest, this is all what one is left with, artificial bouquets and handiwork.

Two sisters, two deflorations, two crimes, twice the work of flowers: the work of the two Kirsanoffs genial, amazing sensibilities.

Dmitri Kirsinov's Menilmontant is considered to be a landmark in the art of film-making. The story is sparse, melodramatic, and brief. The film is barely twenty minutes long. A young girl leaves home after a somewhat vague hatchet murder takes place. She spends time in the seedy streets of Menilmontant, a medieval suburb of Paris. She drifts through a relationship with her sister and man friend.

If you are looking for a strong story and character development, you may be missing the point. Kirsanov was trying to manipulate images in such a way as to get a reaction from his viewer. The bigger story is just a convention on which to hang his moody images. The axe murder with its choppy editing is a very early use of this sort of emotive technique. You are one moment under the flailing axe, interleaved with fast cuts of a howling victim. Later in the film the younger sister is the center of a blurry sensual reverie, her body and her grim surroundings in and out of focus. Silent film as art needs to be taken on its own terms. Kirsanov and other early filmmakers helped to define the way we view, and how we understand the film narrative. That understanding of how the film story works was established quite some time ago, which needs remembering by those of us not around in 1926. It was not foreordained that fast editing, double exposure and other techniques would come into their own. Someone had to prove the power of a restrained use of these formal ideas. Kirsanov did this in 1926.

If you are looking for a strong story and character development, you may be missing the point. Kirsanov was trying to manipulate images in such a way as to get a reaction from his viewer. The bigger story is just a convention on which to hang his moody images. The axe murder with its choppy editing is a very early use of this sort of emotive technique. You are one moment under the flailing axe, interleaved with fast cuts of a howling victim. Later in the film the younger sister is the center of a blurry sensual reverie, her body and her grim surroundings in and out of focus. Silent film as art needs to be taken on its own terms. Kirsanov and other early filmmakers helped to define the way we view, and how we understand the film narrative. That understanding of how the film story works was established quite some time ago, which needs remembering by those of us not around in 1926. It was not foreordained that fast editing, double exposure and other techniques would come into their own. Someone had to prove the power of a restrained use of these formal ideas. Kirsanov did this in 1926.

After the violent and brutal death of their parents, two sisters leave to the big city to live. There, one of the sisters falls in love with a young man, but he is unfaithful and she is left having to deal with her own lost dreams and a baby without a job or a friend.

This is an interesting experimental film. It shows a lot more violence and sex than typically shown at the time, and yet it is very contemplative and serene in parts. However, as a subject of lost dreams, mostly it's very tragic. The image of interest here is the recurring motif of water. Water seems to provide all of the "insanity," including the boy seemingly coming from a spilt water barrel and a long montage of the woman contemplating something drastic as she looks out over the river.

It's powerfully affecting. It's strongest when hectic, during death or violence (beginning and end) or the sudden change from the serene quiet of the country to the speed and confusion of the city. It is a tragedy in every way, as lives are shattered in one way or another until a rather biting climax.

--PolarisDiB

This is an interesting experimental film. It shows a lot more violence and sex than typically shown at the time, and yet it is very contemplative and serene in parts. However, as a subject of lost dreams, mostly it's very tragic. The image of interest here is the recurring motif of water. Water seems to provide all of the "insanity," including the boy seemingly coming from a spilt water barrel and a long montage of the woman contemplating something drastic as she looks out over the river.

It's powerfully affecting. It's strongest when hectic, during death or violence (beginning and end) or the sudden change from the serene quiet of the country to the speed and confusion of the city. It is a tragedy in every way, as lives are shattered in one way or another until a rather biting climax.

--PolarisDiB

Você sabia?

- CuriosidadesPauline Kael said this was her favorite film of all time.

- Versões alternativasThis film was published in Italy in an DVD anthology entitled "Avanguardia: Cinema sperimentale degli anni '20 e '30", distributed by DNA Srl. The film has been re-edited with the contribution of the film history scholar Riccardo Cusin . This version is also available in streaming on some platforms.

- ConexõesFeatured in The language of the silent cinema 1895-1929 - Part II: 1926-1929 (1973)

Principais escolhas

Faça login para avaliar e ver a lista de recomendações personalizadas

Detalhes

- Tempo de duração38 minutos

- Cor

- Mixagem de som

- Proporção

- 1.33 : 1

Contribua para esta página

Sugerir uma alteração ou adicionar conteúdo ausente

Principal brecha

By what name was Ménilmontant (1926) officially released in Canada in English?

Responda