Um correspondente de guerra frustrado, incapaz de encontrar a guerra que lhe foi pedido para cobrir, toma o caminho arriscado de apropriar-se da identidade de um conhecido traficante de arma... Ler tudoUm correspondente de guerra frustrado, incapaz de encontrar a guerra que lhe foi pedido para cobrir, toma o caminho arriscado de apropriar-se da identidade de um conhecido traficante de armas morto.Um correspondente de guerra frustrado, incapaz de encontrar a guerra que lhe foi pedido para cobrir, toma o caminho arriscado de apropriar-se da identidade de um conhecido traficante de armas morto.

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Artistas

- Prêmios

- 5 vitórias e 2 indicações no total

- Robertson

- (as Chuck Mulvehill)

- Hotel Clerk

- (não creditado)

- Murderer's accomplice

- (não creditado)

- Cameraman

- (não creditado)

Avaliações em destaque

Directed by Michelangelo Antonioni and written alongside Mark Peploe and Peter Wollen, 'The Passenger' is an intriguing, atmospheric drama exploring the complexities of truth, identity and isolation. It is a subtle, low-key film that doesn't rely on garrulous dialogue to forward the narrative, and is open to interpretation in many ways. Antonioni strikes a perfect balance between visual and oral storytelling, using Locke's journey to contemplate the impermanence of identity, the mysteries of truth and the devastation of alienation. Though Locke escapes from his unfulfilling life, he cannot run from his past. Nor can he escape the past associated with his new identity, or the fate attached to it.

Here, one could say that Antonioni is suggesting that identity is not something one can easily define or control, but rather something that one has to constantly negotiate and question. He uses Locke's story to posit that identity is not necessarily a source of meaning or fulfilment, but rather one of confusion and alienation. Furthermore, the alienation Locke feels is not just with his environment and with those around him, but with himself. He struggles throughout the film with his sense of purpose, and only by embracing his alienation does he find a potential source of new perspectives and experiences. In this way, Antonioni shows how alienation can positively affect one's life.

Additionally, the notions of truth and reality being stable and fixed concepts are put to question, as every character in the film is involved in a lie, in one way or another. The world of 'The Passenger' is one riddled with contradictions and uncertainties, in terms of perception and beliefs. The film shows us that truth is elusive, and not necessarily a source of clarity or certainty, but rather one of befuddlement and melancholy. As is the case with the themes of identity and alienation, Antonioni's exploration of truth and reality is one that feels consistently fresh and intriguing throughout 'The Passenger'; making its narrative one that you'd be hard pressed to forget.

Despite this depth and complexity of narrative, it is the cinematography that is the real draw here, which is epic and atmospheric. Luciano Tovoli's utilisation of long takes and natural lighting creates a realistic and immersive style contrasted with the alienating world Locke finds himself in. His artful framing and composition carries symbolic, expressive meanings- such as the use of windows and mirrors to create frames within frames, suggesting Locke's entrapment and isolation.

Tovoli also makes excellent use of zooms, pans, tilts and tracking shots to create dynamic and fluid transitions between spaces and perspectives, mirroring Locke's search for truth and identity. His handling of a seven-minute tracking shot at the end of the movie is particularly breath-taking; perhaps one of the finest such sequences ever put to film. This intense scene acts as a metaphor for Locke's journey, as well as creating a contrast between the realistic and symbolic, challenging our perception and understanding of reality, as it shows us things that are not possible or logical.

Through its use of long takes, deep focus and natural lighting- creating a modernist, minimalist aesthetic that reflects the characters' alienation- the film is reminiscent of Antonioni's previous 'L'Avventura' trilogy; though in colour and on location. Conversely, some may compare the visual aesthetics to those of Yasujiro Ozu or Robert Bresson, who used natural lighting to generate a realistic and contemplative style that explored the human condition in a profound, assured way. Whatever the case, the cinematography of 'The Passenger' is arguably its greatest strength, enhancing the film's themes and narrative by creating a contrast between the realistic and the symbolic; while always remaining visually stunning.

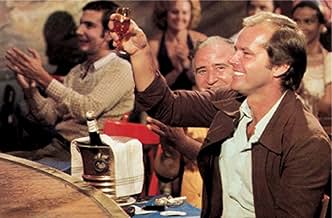

'The Passenger' stars Jack Nicholson as Locke, delivering a measured performance that rivals his similarly understated efforts in 'The King of Marvin Gardens' and 'Five Easy Pieces.' From his opening moments- trapped in the desert unable to communicate with anyone- to his last, Nicholson mesmerizes. Consistently underplaying it, he never sets a foot wrong performance-wise, sharing an easy chemistry with co-star Maria Schneider that makes watching them together a real treat. For her part, Schneider brings a light touch to proceedings and- though her role is a little underwritten- shines throughout; leaving an indelible impression on the viewer.

Having said all that, if you don't appreciate abstract, existentialist films, or narratives that are open to interpretation and draped in mystery and intrigue; 'The Passenger' may not be for you. It is a complex film that doesn't clearly or definitely state its intentions or explain its meanings. Beautifully shot and strongly acted, 'The Passenger' examines some profound themes in a mature, understated way, and is a highlight of Antonioni's oeuvre. If you do appreciate the abstract, the mysterious and the profound, then hop on board 'The Passenger': it's one hell of a ride.

Some may find the opening twenty minutes of the film, where there is virtually no dialogue, hard-going but this perfectly illustrates the sparse and confusing environment of the North African desert where the film begins. We are also treated to a marvellous scene between Locke and the man whose identity he later assumes where a tape recording and flashback are ingeniously merged into one and then separated again. Antonioni creates a mood that is almost indefinable throughout, a kind of hollow detachment which is exactly the perspective that Locke has on the world which has gradually worn him down yet the director still manages to conjure up power and simple romance between Locke and the girl he meets who is played by Maria Schneider. The film was not a hit at the box-office which is not surprising considering it's uncommercial style but artistically and cinematically it is a triumph of innovation.

Despite its power and polemic against journalism, Professione: Reporter is also an understated movie from start to finish, made for a grown-up audience. Nothing is spelt out for you. However, the movie is strewn throughout with powerful and evocative visual clues, so it's nonetheless up to you as an attentive viewer to pick up (the early scene of Locke's Jeep getting stuck in the African desert sand, anyone?), or even soak them up unconsciously. As with all Antonioni, every shot in this movie is worthy of analysis and admiration. Bergman once said about the Italian that he could create some arresting individual images, but was incapable of stringing them all together in the sequence of a palatable movie: sorry Ingmar, old man - as much as I feel in awe of your craft, you're talking nonsense, here. However, I can't believe Antonioni once had the cheek to say he improvises each scene as he goes along (see his IMDb quotes page). There isn't a chance in hell these meticulously crafted, immaculately framed and composed movies are not also carefully premeditated. Clearly, Antonioni was trying to start a myth about himself along the lines of the one about Mozart composing his music straight onto the page, as dictated by God. In Professione: Reporter, I was especially in awe of the sequence involving the single long take from the window of Locke's last hotel room in an unnamed, dusty Spanish village. Regarding Maria Schneider, it truly is a shame she wasn't the star in a greater number of successful movies. Her ambiguity makes it very difficult to keep one's eyes off her when she's on screen. She looks like a cross between a boy, a girl and something cutely ape-like (I mean it in a good way!).

I would like to warn viewers of the inclusion of footage of a real execution - again, this was a film within the film. Personally, I found it very disturbing, which is why I'm mentioning it here.

"I'd like to enquire about flights," Locke asks a hotel clerk. He seeks to escape his past. Later in the film, as he rides a cable cart, Locke spreads his arms and soars like a bird. He's flying, finally enjoying a brief moment of freedom.

The theme of identity, and Locke's name itself, immediately recalls the writings of English philosopher John Locke. Locke believed in the concept of the "tabula rasa" or blank slate. He believed that it was our experiences that defined us as people and that the only way to escape who we are is to effectively erase our history and cut ourselves off from experiences.

Throughout his writings, Locke emphasised the individual's freedom to author his or her own soul. Each individual was free to define his character, but his basic identity as a member of the human species could not be altered. So Locke had two ideas at war. Firstly the belief that the individual was free to author his own life, and secondly the belief that human nature is rigid and unchangeable. It is from this presumption of a free, self authored mind, combined with a sense of rigid human nature, that the Lockean doctrine of "natural" rights is derived.

In Antonioni's film, Nicholson articulates these ideas himself. He is trapped between wanting to be free and having to fulfil duties/roles/tasks embedded in the new persona he has acquired. While responding to a comment that all PLACES are the same, he even argues that it's actually the PEOPLE that are the same. That everyone conforms to specific cultural archetypes. The film's original title, "Profession: Reporter", highlights this point best.

Nicholson's character is desperate to escape this. Like his character in "Five Easy Pieces", he wants some unmappable freedom. He wants to be an individual. Beyond this, though, he wants to stay blank. In what is perhaps the film's most joyous moment, a female character asks Locke what he's running from. He tells her to turn her back to the front of the car. What occurs next is an instant of spontaneous elation and giddy happiness, as she watches the road rush away behind them.

But what people fail to notice during this scene, is that she is in fact watching the past. By facing her previous experiences (which Locke refuses to do) she is happy. Happiness comes from her memories and past encounters, while Locke is miserable simply because he refuses to acknowledge his past experiences.

Throughout the film Locke is asked whether he thinks "the landscape" is beautiful. Once he answers "no", another time he absent mindedly answers "yes", but Antonioni stresses that Locke is really not paying attention. Locke intentionally avoids absorbing beauty or new experiences in an effort to remain in a constant state of rebirth.

These themes are culminated in a brilliant "blind man" story towards the end of the film. Locke, a journalist who specialises in seeing and recording the truth, is painfully attuned to what he calls the "dirt" of the world. As such, he chooses to remain blind. A blank slate.

Antonioni is particularly good at endings and the final shot of "The Passenger" really elevates the whole film. Like the dead man, whose identity he took on, Locke dies alone and face down in a bed. His ex wife pops up and states that she never knew him, but nobody seems to care.

9/10- A great film, worth two viewings. It captures a profound sense of isolation and sadness. Antonioni's camera seems to capture the immense tiredness of the body. Rather than portray experiences, he shows what remains of past experiences. He shows what comes afterwards, when everything has been said. The middle portion of the film is slow and seems to be lacking some sort of superficial drama, but things build nicely and the final payoff well is worth the wait.

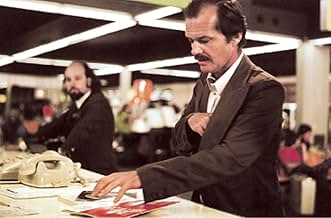

As with the director's most celebrated film, Blowup (1966), The Passenger also deals with the ideas of sight and perception, and with a character - in this case a writer/television reporter - who literally creates his own story as the film progresses. With these factors in places we have an absolutely fascinating piece of work; one filled with endless ideas of interpretation and reinterpretation as we look at the accumulation of character information and the vague scenes that seem to suggest the background of this character in relation to his decisions that come to inform the direction of the plot. With this, we again come back to that central notion of identity and how it governs our journey through life, with the earliest scenes showing Nicholson's character to be lost (both literally and figuratively) in a pensive, limbo-like existence and finding his way out of this torturous situation by attempting to step into the shoes of a completely different character (again, an idea expressed in both the literal and metaphorical sense of the term). These ideas are depicted through Antonioni's fantastic use of time and space, as he places Nicholson, first as an insignificant speck in the midst of the African desert, and then eventually against an ever changing backdrop of exciting and exotic European locales, to literally convey his lack of significance within the world that he inhabits.

Nevertheless, the real enjoyment of the film comes from the eventual realisation that this character makes on the nature of existence and his place within it, and how Antonioni suggests this through his typically rigid and starkly beautiful direction and the actual mechanisms of the plot. As ever with Antonioni's work, the narrative here is structured in a subjective and episodic manner, moving from one scene to the next while offering us snatches of information that we can collect and consider within the perspective of that penultimate scene that seems to put the rest of the film into a kind of context. The director also uses flashbacks and cutaways to scenes that we assume have some precedence over the journey that the character is taking, though again, it could just as easily be connected to the political climate that the film suggests through the documentary footage shot by Nicholson's character before his eventual self-imposed exile from himself. Here, the implication of the film's English title becomes clear, with the character of David Locke becoming a literal passenger in his own life; an empty vessel just drifting through existence with no real interaction, boxed in by the confines of a disintegrating marriage and tied to a job that is slowly sucking the very essence from his being.

Though the film is as minimal and subtle as many of Antonioni's earlier films, such as his grand cinematic gesture, the so-called "alienation trilogy", comprising of the films L'avventura (1960), La Notte (1961) and L'Eclisse (1962), the ultimate themes are incredibly affecting and heartbreaking in their finality; with Locke becoming the representation of the literal lost soul, a ghost in his own life who finds escape through imitation, only to end up reliving the same nightmare as if trapped within some endless loop. For me, it is easy to identify with the ideas here; with the central concept of remaking your own life as someone else entirely - or to live our lives from another perspective - coming back to the often mistaken belief that the grass is always greener on the other side. This notion is suggested throughout the film, from the first very meeting between Locke and the enigmatic Robertson, to that final scene between David and the mysterious girl, in which Locke relates the somewhat heartbreaking parable of the blind man who, after finally regaining his sight on the eve of his 40th birthday, is literally overwhelmed by what a terrible state the world is in.

Metaphors run rife through the film, from Antonioni's visual abstractions within the frame, to the subtle use of wordplay within the script. The ending then ties the whole thing together with a masterful display of technical virtuosity and one of the great, enigmatic questions of Antonioni's career. It is sad, mostly in the same way that the endings of La Notte and L'Eclisse were sad, suggesting a thread of resigned disappointment and the rejection of escape in favour of the easiest option. Ultimately though, the film is deeper, more affecting and more fascinating than any of this particular review might suggest; with Antonioni producing one of his very greatest films, aided by the excellent performances from Nicholson and Maria Schneider, and that continually evasive and hypnotic tone of wandering melancholy, as we move slowly towards that inevitable final, and one of Antonioni's boldest and most purely defined artistic statements.

Você sabia?

- CuriosidadesWhen Michelangelo Antonioni received his honorary Oscar in 1995, the Academy asked Jack Nicholson to present it to him.

- Erros de gravaçãoThere are a couple of inaccuracies in the displayed details of Locke's Air Afrique air ticket that was evidently issued in Douala, Cameroon in August 1974. The name of Fort-Lamy (Chad's neighboring capital city) became N'djamena in early 1973, and Paris is written in Italian ("Parigi") which would not have occurred in French-speaking Douala.

- Citações

The Girl: Isn't it funny how things happen? All the shapes we make. Wouldn't it be terrible to be blind?

David Locke: I know a man who was blind. When he was nearly 40 years old, he had an operation and regained his sight.

The Girl: How was it like?

David Locke: At first he was elated... really high. Faces... colors... landscapes. But then everything began to change. The world was much poorer than he imagined. No one had ever told him how much dirt there was. How much ugliness. He noticed ugliness everywhere. When he was blind... he used to cross the street alone with a stick. After he regained his sight... he became afraid. He began to live in darkness. He never left his room. After three years he killed himself.

- Cenas durante ou pós-créditosLeo, the MGM lion, which normally precedes the opening credits of MGM movies, has been supplanted by "BEGINNING OUR NEXT 50 YEARS". Leo then returns in the center with "GOLDEN ANNIVERSARY" on either side of it.

- Versões alternativasSeven minutes were added to the 2005-2006 re-release version, including a brief shot of a nude Maria Schneider in bed with Jack Nicholson in the Spanish hotel.

- ConexõesFeatured in Z Channel: A Magnificent Obsession (2004)

Principais escolhas

- How long is The Passenger?Fornecido pela Alexa

Detalhes

- Data de lançamento

- Países de origem

- Central de atendimento oficial

- Idiomas

- Também conhecido como

- The Passenger

- Locações de filme

- Fort Polignac, Algéria(desert scenes, setting: Chad)

- Empresas de produção

- Consulte mais créditos da empresa na IMDbPro

Bilheteria

- Faturamento bruto nos EUA e Canadá

- US$ 620.155

- Fim de semana de estreia nos EUA e Canadá

- US$ 24.157

- 30 de out. de 2005

- Faturamento bruto mundial

- US$ 769.503