AVALIAÇÃO DA IMDb

7,7/10

14 mil

SUA AVALIAÇÃO

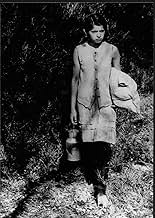

Uma jovem mulher que vive no campo francês sofre humilhações constantes às mãos do alcoolismo e de seus semelhantes.Uma jovem mulher que vive no campo francês sofre humilhações constantes às mãos do alcoolismo e de seus semelhantes.Uma jovem mulher que vive no campo francês sofre humilhações constantes às mãos do alcoolismo e de seus semelhantes.

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Artistas

- Prêmios

- 5 vitórias e 1 indicação no total

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Elenco e equipe completos

- Produção, bilheteria e muito mais no IMDbPro

Avaliações em destaque

Among the best things that can happen to me as a viewer is to watch a filmmaker grow into mastery, and I've just gone through a series of viewing where Bresson grew before my eyes. He wasn't a master before Balthazar in my estimation but he was one now.

See, he had started with ambitious work in Diary of a Priest, but something must have troubled him, the spiritual search was coming off as emotional anguish, resulting in sentimentality. His next three were all about finding ways to quell this, fasting the eye, muting the emotion.

This is all the more reason to celebrate him, because it could have gone either way. He could have turned out film after film where he mutes expression and turns actors into bare stumps and called it pure. But if this was purity, where was the life in which the pure is woven through? Bresson matters I believe because he left the stone floor of his ascetic phase to grow into this, his sculpting phase.

This is a sculpture of moving image and sound, even more so than Balthazar, even more purely about the rooms and spaces in which a young girl faces the duplicity of life. It's all in how he chisels the air with the camera, he does this in three parts.

The day before, with its moments of small everyday cruelty and unexpected kindness alike. She has a beautiful voice but won't sing with her classmates until forced, a passing woman unexpectedly gives her money for the bumping cars, but her dalliance with a boy is cut short and she has to go sit with her father. It's heart-aching because all she needs is someone to mind her and no one does outside of making her behave how they want to, most of us have been savaged this way as kids.

The night of unfathomable emotions out in the woods, and look how masterfully. Why she does what she does in the cabin, why she swears to protect his secret and professes love, perhaps intuitively protecting herself, perhaps asserting herself against authority, this is all as unfathomable as why the man goes back out to commit violence. It's all in that shot where the two men laugh, for no reason other than all this being absurd, beneath a dark sky, and the wind that blows all through the night.

In the third part of the film we have the day after, with this complicated human nature brought to the stark light of what other people think. Bresson shows us judgment and cynicism, and even the old woman's advice about death is waved off; too musty for a young girl, more advice.

So how poignant to see this shift in Bresson? He gives us by the end a more eloquent Jeanne D'arc, now the dogmatist interrogators become your small-minded neighbors and Joan is neither pure nor certain in any way about the truth of what she experienced. No ceremonial death. And how deep it cuts, that she may have wanted to ask her mother for advice, unburden the confusion, but has to go through it alone.

So after a series of Bresson viewings, I will come to rest here. Antonioni would take home the Palm that year but Bresson had conquered his obstacles and arrived fully. The title of Tarkovsky's book best describes what he does here, and you can see the Tati influence as a new tool that he didn't have back in Pickpocket. He sculpts an external time, but now in such a way that the pure is found where it grows roots and rustles, among life.

It would be Tarkovsky's turn now to shoulder this legacy, and Dreyer's, asking himself, what kind of time? We dream and yearn with an asymmetric logic and mingle with our reflection. It would be one of the great leaps in the cinema but for that we'd have to go forward.

See, he had started with ambitious work in Diary of a Priest, but something must have troubled him, the spiritual search was coming off as emotional anguish, resulting in sentimentality. His next three were all about finding ways to quell this, fasting the eye, muting the emotion.

This is all the more reason to celebrate him, because it could have gone either way. He could have turned out film after film where he mutes expression and turns actors into bare stumps and called it pure. But if this was purity, where was the life in which the pure is woven through? Bresson matters I believe because he left the stone floor of his ascetic phase to grow into this, his sculpting phase.

This is a sculpture of moving image and sound, even more so than Balthazar, even more purely about the rooms and spaces in which a young girl faces the duplicity of life. It's all in how he chisels the air with the camera, he does this in three parts.

The day before, with its moments of small everyday cruelty and unexpected kindness alike. She has a beautiful voice but won't sing with her classmates until forced, a passing woman unexpectedly gives her money for the bumping cars, but her dalliance with a boy is cut short and she has to go sit with her father. It's heart-aching because all she needs is someone to mind her and no one does outside of making her behave how they want to, most of us have been savaged this way as kids.

The night of unfathomable emotions out in the woods, and look how masterfully. Why she does what she does in the cabin, why she swears to protect his secret and professes love, perhaps intuitively protecting herself, perhaps asserting herself against authority, this is all as unfathomable as why the man goes back out to commit violence. It's all in that shot where the two men laugh, for no reason other than all this being absurd, beneath a dark sky, and the wind that blows all through the night.

In the third part of the film we have the day after, with this complicated human nature brought to the stark light of what other people think. Bresson shows us judgment and cynicism, and even the old woman's advice about death is waved off; too musty for a young girl, more advice.

So how poignant to see this shift in Bresson? He gives us by the end a more eloquent Jeanne D'arc, now the dogmatist interrogators become your small-minded neighbors and Joan is neither pure nor certain in any way about the truth of what she experienced. No ceremonial death. And how deep it cuts, that she may have wanted to ask her mother for advice, unburden the confusion, but has to go through it alone.

So after a series of Bresson viewings, I will come to rest here. Antonioni would take home the Palm that year but Bresson had conquered his obstacles and arrived fully. The title of Tarkovsky's book best describes what he does here, and you can see the Tati influence as a new tool that he didn't have back in Pickpocket. He sculpts an external time, but now in such a way that the pure is found where it grows roots and rustles, among life.

It would be Tarkovsky's turn now to shoulder this legacy, and Dreyer's, asking himself, what kind of time? We dream and yearn with an asymmetric logic and mingle with our reflection. It would be one of the great leaps in the cinema but for that we'd have to go forward.

After I watched Bresson's "Au Hasard Balthazar" a few years ago, I was advised by a friend to watch "Mouchette" next. I told him I wasn't particularly struck by the character development and the portrayal of humans and emotions in the former, and learned that I had the exact same problems with the latter.

The girl is amazing. Her justified rebellious behavior and her unique and authentic appearance really shine in this movie. Also, the photography in the film is very well done, as I would have dared to expect from Bresson. Technically, this movie certainly is very good.

However, the way people interact in this movie often doesn't make sense to me. And I know movies aren't obligated to be realistic, but this movie certainly has a lot of ingredients on board to make you believe it's trying to be realistic. It's not an absurd or surrealistic film where you won't have to expect to be able to completely understand emotions and social situations. The consequence is - to me at least - that my compassion doesn't know how to handle the situation. First something sad happens, and I get moved, but then there's weird silences or poetic expressions (not necessarily verbal) which don't fit the realistic context and interrupt the immersion if you ask me.

Another friend of mine with whom I discussed this topic mentioned a good point however: perhaps you should let go of the expectation to be moved emotionally. Doesn't the movie just try to display the story, possibly telling you to accept life for what it is without necessarily trying to move you? Well observed, it's possible. I still believe the movie could benefit strongly if it was more emotionally involving though.

I have had this discussion with a lot of people about several movies, and it seems nobody either understands or agrees with me on this subject. Therefore, I'm even more aware of how subjective this point of view is. Obviously, this movie isn't a classic for no reason and I'm sure it has plenty of qualities that let people appreciate it so much. Not entirely my cup of tea though.

The girl is amazing. Her justified rebellious behavior and her unique and authentic appearance really shine in this movie. Also, the photography in the film is very well done, as I would have dared to expect from Bresson. Technically, this movie certainly is very good.

However, the way people interact in this movie often doesn't make sense to me. And I know movies aren't obligated to be realistic, but this movie certainly has a lot of ingredients on board to make you believe it's trying to be realistic. It's not an absurd or surrealistic film where you won't have to expect to be able to completely understand emotions and social situations. The consequence is - to me at least - that my compassion doesn't know how to handle the situation. First something sad happens, and I get moved, but then there's weird silences or poetic expressions (not necessarily verbal) which don't fit the realistic context and interrupt the immersion if you ask me.

Another friend of mine with whom I discussed this topic mentioned a good point however: perhaps you should let go of the expectation to be moved emotionally. Doesn't the movie just try to display the story, possibly telling you to accept life for what it is without necessarily trying to move you? Well observed, it's possible. I still believe the movie could benefit strongly if it was more emotionally involving though.

I have had this discussion with a lot of people about several movies, and it seems nobody either understands or agrees with me on this subject. Therefore, I'm even more aware of how subjective this point of view is. Obviously, this movie isn't a classic for no reason and I'm sure it has plenty of qualities that let people appreciate it so much. Not entirely my cup of tea though.

It seems entirely appropriate that the film opens with the metaphor of birds being snared as this seems to apply not only to Mouchette's life, but to Bresson's approach to the viewer as well.

For what, after all, is the director attempting to do here? Are we really to regard this as an unblinking gaze into the life of an abused, outcast girl? If so, why is Bresson so intent on excluding even the most fleeting moments of joy (or at least humor) that enter even the darkest of lives (I believe a philosopher once said "alas, joy too must have its day")? It is pretty telling that the one scene involving happiness for Mouchette is the most monotonous and lifeless in the picture (the bumper cars). Not only are we not allowed to experience her joy, but Bresson is careful to distance us from the real experience of her pain as well. This is done by the use of "gestures" (particularly prominent in Bresson's later films) that "signify" a character's experience rather than giving us the person's individualized emotional and visceral reactions to events. Thus the assault on Mouchette is shown in a distant, almost pantomimed manner, her relationship with her father is suggested by dropping coins in his hand, a disembodied hand slapping her face, etc. So, are we really to identify with Mouchette, to feel her pain, seeing how her experience of life intersects with our own in only the most symbolic, muted fashion? Is this really "compassion" and is this really Bresson's purpose?

Or is Mouchette a figure that Bresson uses (and dehumanizes), as literally every character in the movie uses her, to achieve other purposes? In this case the selling of a particular view of the world. One which sees the world as a snare, both in its joy and its pain, that is "saved" only by the (symbolic) suffering of the innocent, and transcended/transformed only by death. In other words a viewpoint that that advocates looking beyond (or turning away from)life to find "transcendent" truths. A view based on judgement rather than acceptance. And if this is "the truth" why must so much of what we experience as truth (such as joy, intimacy, occasional feelings of "oneness" with the world) be so forcibly excluded? Are these all really illusions, the world simply a snare? And without acceptance of ALL of Mouchette's reality can she,or any of us, really be redeemed?

Yes, Bresson is a meticulous, incisive, and occasionally powerful filmaker. But is he really honest? Are there some TRUTHS that he can't face (and so desperately restricts his view). In MOUCHETTE we are a little more aware of the puppeteer's strings than usual. 7 out of 10.

For what, after all, is the director attempting to do here? Are we really to regard this as an unblinking gaze into the life of an abused, outcast girl? If so, why is Bresson so intent on excluding even the most fleeting moments of joy (or at least humor) that enter even the darkest of lives (I believe a philosopher once said "alas, joy too must have its day")? It is pretty telling that the one scene involving happiness for Mouchette is the most monotonous and lifeless in the picture (the bumper cars). Not only are we not allowed to experience her joy, but Bresson is careful to distance us from the real experience of her pain as well. This is done by the use of "gestures" (particularly prominent in Bresson's later films) that "signify" a character's experience rather than giving us the person's individualized emotional and visceral reactions to events. Thus the assault on Mouchette is shown in a distant, almost pantomimed manner, her relationship with her father is suggested by dropping coins in his hand, a disembodied hand slapping her face, etc. So, are we really to identify with Mouchette, to feel her pain, seeing how her experience of life intersects with our own in only the most symbolic, muted fashion? Is this really "compassion" and is this really Bresson's purpose?

Or is Mouchette a figure that Bresson uses (and dehumanizes), as literally every character in the movie uses her, to achieve other purposes? In this case the selling of a particular view of the world. One which sees the world as a snare, both in its joy and its pain, that is "saved" only by the (symbolic) suffering of the innocent, and transcended/transformed only by death. In other words a viewpoint that that advocates looking beyond (or turning away from)life to find "transcendent" truths. A view based on judgement rather than acceptance. And if this is "the truth" why must so much of what we experience as truth (such as joy, intimacy, occasional feelings of "oneness" with the world) be so forcibly excluded? Are these all really illusions, the world simply a snare? And without acceptance of ALL of Mouchette's reality can she,or any of us, really be redeemed?

Yes, Bresson is a meticulous, incisive, and occasionally powerful filmaker. But is he really honest? Are there some TRUTHS that he can't face (and so desperately restricts his view). In MOUCHETTE we are a little more aware of the puppeteer's strings than usual. 7 out of 10.

Never before has cinema been this simple and honest. No one makes films with more emotion than Bresson and no one puts less emotion in their films than he. I could cite so many Bressonian cliches and talk of his uniquely personal style which by 1967 was firmly established, especially since he had abandoned the voice-over he used in the 50s. I will point out his use of sound and approach to acting which remain so distinctive and by now so familiar. There is nothing in Mouchette that is new, especially after Balthazar, what remains is the story of Mouchette, told with the utter grace and passion that makes this film a masterpiece that transcends technique, even cinema itself, and makes most cinema look frivolous in the process.

Finally I must mention the films ending, which I rank with that of Balthazar as the most beautiful I have seen.

Finally I must mention the films ending, which I rank with that of Balthazar as the most beautiful I have seen.

My Rating : 9/10

Bresson is heralded as an important filmmaker in world cinema. I absolutely love 'Mouchette' and it is a masterpiece of world cinema. It was on Tarkovsky's top 10 films list he made for Sight & Sound.

Bresson's other famous film Au Hasard Balthasar and Mouchette have common themes of abuse and negligence of the main characters. This film has the formal inevitability of tragedy, and is soaked through with a species of lyrical, desperate sadness. This quality, and the compelling aesthetic seriousness with which Bresson addresses his themes of suffering, compassion and the rural poor, are very remarkable indeed. Mouchette is a visionary, poetic film, fraught with elusive, unsettling meanings: a classic cinematic text.

Bresson is heralded as an important filmmaker in world cinema. I absolutely love 'Mouchette' and it is a masterpiece of world cinema. It was on Tarkovsky's top 10 films list he made for Sight & Sound.

Bresson's other famous film Au Hasard Balthasar and Mouchette have common themes of abuse and negligence of the main characters. This film has the formal inevitability of tragedy, and is soaked through with a species of lyrical, desperate sadness. This quality, and the compelling aesthetic seriousness with which Bresson addresses his themes of suffering, compassion and the rural poor, are very remarkable indeed. Mouchette is a visionary, poetic film, fraught with elusive, unsettling meanings: a classic cinematic text.

Você sabia?

- CuriosidadesIt was rumored for years that the trailer for this film was by Jean-Luc Godard, and he has recently confirmed this by programming it in a self-curated retrospective of his work. The trailer is virtually a miniature essay on (or subversion of) the film, jarringly inter-cutting excerpts from it with a written commentary that calls it "Christian and sadistic."

- Erros de gravação(at around 1 min) The canteen changes position after being dropped.

- ConexõesEdited into Bande-annonce de 'Mouchette' (1967)

- Trilhas sonorasMagnificat

Written by Claudio Monteverdi

Performed by Les Chanteurs de St. Eustache

Conducted by R.P. Émile Martin

Principais escolhas

Faça login para avaliar e ver a lista de recomendações personalizadas

- How long is Mouchette?Fornecido pela Alexa

Detalhes

- Tempo de duração

- 1 h 21 min(81 min)

- Cor

- Mixagem de som

- Proporção

- 1.66 : 1

Contribua para esta página

Sugerir uma alteração ou adicionar conteúdo ausente