Alice no País das Maravilhas

Título original: Alice in Wonderland

AVALIAÇÃO DA IMDb

6,7/10

1,1 mil

SUA AVALIAÇÃO

Adicionar um enredo no seu idiomaA girl named Alice falls down a rabbit-hole and wanders into the strange Wonderland.A girl named Alice falls down a rabbit-hole and wanders into the strange Wonderland.A girl named Alice falls down a rabbit-hole and wanders into the strange Wonderland.

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Artistas

Jo Maxwell Muller

- Alice's Sister

- (as Jo Maxwell-Muller)

Michael Redgrave

- Caterpillar

- (as Sir Michael Redgrave)

Anthony Trent

- Fish Footman

- (as Tony Trent)

- …

Wilfrid Lawson

- Dormouse

- (as Wilfred Lawson)

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Elenco e equipe completos

- Produção, bilheteria e muito mais no IMDbPro

Avaliações em destaque

Working with a shoestring budget director Jonathan Miller was able to persuade an impressive cast (Peter Sellers, Sir Michael Redgrave, Sir John Gielgud, Peter Cook, Alan Bennett, Michael Gough, Wilfred Brambell, Wilfred Lawson, Leo McKern, Malcolm Muggeridge, Finlay Currie) to make cameo appearances in his BBC production of "Alice in Wonderland". The results are mixed, with some bright spots (especially the few improvisations Miller left in).

Miller dresses his cast like Victorians, rather than making them look like animals (after all, he says in his commentary, the typical way of doing Alice is to take big stars and then cover them up with animal heads so you can't see who they are).

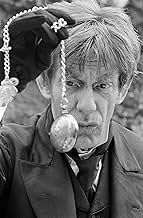

He takes the book literally. For instance, the Hatter and the March Hare are mad in a real way rather than the typically overblown cartoonish way. Peter Cook's Hatter is soft-spoken, laughing and agreeable, his lines always sounding like non sequiturs; while Michael Gough's March Hare is defensive, suspicious, and genuinely troubling.

The best scene, which probably best captures what Miller was working for, was Muggeridge's Gryphon and Gielgud's Mock Turtle. The fey White Rabbit of Wilfred Brambell ("A Hard Day's Night") is a delight. Peter Sellers, appearing all too briefly, has an amusing bit of business (Miller in his commentary doesn't like it but it suits the scene admirably and in this case Sellers the slapstick authority knew what he was doing better than the director -- the scene cries out for what he does). Michael Redgrave is phenomenal in his all-too-brief turn as the caterpillar, but the scene is damaged by truncating the poem "You are Old, Father William" to the point that it makes no sense on any level. Peter Cook's Hatter is engaging at first but his one-note madness is quickly tiresome. More interesting at the tea party is Wilfred Lawson's Door Mouse (watch his hands -- he knows his business); and Michael Gough ("Batman"), who has an aura of danger.

The pros in the cast all do their best, and no fault can be found with the big-name stars who are doing good work for peanuts.

Miller's concept of Alice is the primary reason the film ultimately doesn't work. The girl he chose as Alice has a very interesting face, and is wonderfully untraditional. Sometimes her delivery (heard half in voice-over and half in dialog) shows promise. But Miller, probably to accentuate the dreamlike fixation, has her walk through the movie like a somnambulist, not becoming involved. The little emoting he does allow is almost always to show Alice's rudeness. For the most part her facial expression is fixed and unengaged, and this is Miller's fault.

The cutting from scene to scene is abrupt. Part of this is probably Miller's continued obsession with the working of dreams, and partly because a lot of transitional material was cut out at the request of the bigwigs to make the show move faster. And because Miller is quite literal with Carroll, he makes the mad tea party actually have the monotonous languor of people trapped in a long afternoon tea that will never stop -- and it becomes tedious.

Oddly, on the DVD, far better than the movie is the director's audio track. Jonathan Miller gives a full 80 minute's description of what he tried to do (and what price limitations left him able to do); and when the movie is seen in that light, it makes a lot more sense. Sometimes Miller explains why things were done, sometimes he desperately tries to justify what was done. In all cases, his commentary is interesting and he never falls into the trap of describing what's going on, but always why it's going on.

The movie looks good, and individual turns by actors are superb, but the whole is less than the sum of its parts.

Miller dresses his cast like Victorians, rather than making them look like animals (after all, he says in his commentary, the typical way of doing Alice is to take big stars and then cover them up with animal heads so you can't see who they are).

He takes the book literally. For instance, the Hatter and the March Hare are mad in a real way rather than the typically overblown cartoonish way. Peter Cook's Hatter is soft-spoken, laughing and agreeable, his lines always sounding like non sequiturs; while Michael Gough's March Hare is defensive, suspicious, and genuinely troubling.

The best scene, which probably best captures what Miller was working for, was Muggeridge's Gryphon and Gielgud's Mock Turtle. The fey White Rabbit of Wilfred Brambell ("A Hard Day's Night") is a delight. Peter Sellers, appearing all too briefly, has an amusing bit of business (Miller in his commentary doesn't like it but it suits the scene admirably and in this case Sellers the slapstick authority knew what he was doing better than the director -- the scene cries out for what he does). Michael Redgrave is phenomenal in his all-too-brief turn as the caterpillar, but the scene is damaged by truncating the poem "You are Old, Father William" to the point that it makes no sense on any level. Peter Cook's Hatter is engaging at first but his one-note madness is quickly tiresome. More interesting at the tea party is Wilfred Lawson's Door Mouse (watch his hands -- he knows his business); and Michael Gough ("Batman"), who has an aura of danger.

The pros in the cast all do their best, and no fault can be found with the big-name stars who are doing good work for peanuts.

Miller's concept of Alice is the primary reason the film ultimately doesn't work. The girl he chose as Alice has a very interesting face, and is wonderfully untraditional. Sometimes her delivery (heard half in voice-over and half in dialog) shows promise. But Miller, probably to accentuate the dreamlike fixation, has her walk through the movie like a somnambulist, not becoming involved. The little emoting he does allow is almost always to show Alice's rudeness. For the most part her facial expression is fixed and unengaged, and this is Miller's fault.

The cutting from scene to scene is abrupt. Part of this is probably Miller's continued obsession with the working of dreams, and partly because a lot of transitional material was cut out at the request of the bigwigs to make the show move faster. And because Miller is quite literal with Carroll, he makes the mad tea party actually have the monotonous languor of people trapped in a long afternoon tea that will never stop -- and it becomes tedious.

Oddly, on the DVD, far better than the movie is the director's audio track. Jonathan Miller gives a full 80 minute's description of what he tried to do (and what price limitations left him able to do); and when the movie is seen in that light, it makes a lot more sense. Sometimes Miller explains why things were done, sometimes he desperately tries to justify what was done. In all cases, his commentary is interesting and he never falls into the trap of describing what's going on, but always why it's going on.

The movie looks good, and individual turns by actors are superb, but the whole is less than the sum of its parts.

This is an experimental TV-movie from the BBC's "Wednesday Play" anthology. That series was always willing to risk trying something different, and this ambitious, low-budget "Alice" is certainly different. I don't exactly *enjoy* this film, but it's certainly fascinating.

I appreciate it as an experiment in what television could do. I admire the cast of iconic and talented Britons who wouldn't normally coincide in the same project: Peter Sellers, John Gielgud, Leo McKern (in drag as the Duchess), Michael Redgrave, Peter Cook, Wilfrid Brambell, Alan Bennett, Malcolm Muggeridge, etc.

I also admire the creativity it took to imagine this quintessentially British tale accompanied by Ravi Shankar music.

Some viewers may find the film too creepy and surreal, but the original book is pretty disturbing to begin with. This film is fairly incoherent, but then so is the book, which follows the ever-shifting logic of a dream.

The biggest problem (aside from pacing that now seems too leisurely) is that Miller's production assumes you already know what's going on. For instance, it assumes you know that the two men dressed as... um... men are actually the Gryphon and the Mock Turtle.

In other words, this is an "Alice" for people who are already overdosed on adaptations of "Alice," and who might appreciate a weirdly different take on the familiar story. Or to narrow that audience a bit, people age 12 and up who might appreciate a different take on the story.

I appreciate it as an experiment in what television could do. I admire the cast of iconic and talented Britons who wouldn't normally coincide in the same project: Peter Sellers, John Gielgud, Leo McKern (in drag as the Duchess), Michael Redgrave, Peter Cook, Wilfrid Brambell, Alan Bennett, Malcolm Muggeridge, etc.

I also admire the creativity it took to imagine this quintessentially British tale accompanied by Ravi Shankar music.

Some viewers may find the film too creepy and surreal, but the original book is pretty disturbing to begin with. This film is fairly incoherent, but then so is the book, which follows the ever-shifting logic of a dream.

The biggest problem (aside from pacing that now seems too leisurely) is that Miller's production assumes you already know what's going on. For instance, it assumes you know that the two men dressed as... um... men are actually the Gryphon and the Mock Turtle.

In other words, this is an "Alice" for people who are already overdosed on adaptations of "Alice," and who might appreciate a weirdly different take on the familiar story. Or to narrow that audience a bit, people age 12 and up who might appreciate a different take on the story.

"Who am I?" asks a shabbily dressed, scruffy-haired incarnation of Lewis Carroll's immemorial little girl lost. Of course, the answer's come in various forms ever since such cinematic endeavors as Cecil Hepworth's "Alice in Wonderland," made in 1903 (at 12 minutes, the longest British film of the day; Cecil, you'll remember, two years later made the world's first "dog star" with his monumentally successful "Rescued by Rover," which was shown so many times that the celluloid literally deteriorated, forcing the filmmakers to completely "re-produce" it two more times; his "Alice in Wonderland," unfortunately, did not boast such a success, and thus all we have today is something that looks as though it tumbled down the rabbit hole one too many times). But enough of this sluice at the bottom of the March Hare's treacle well, eh?

Made for the BBC's The Wednesday Play television series, Jonathan Miller's take on the subject matter is, as is traditionally the case, a unique one. With a budget approximating nothing more than his usual "taped stage plays" for which he previously gained great renown (think preter-PBS), Miller decided to illustrate what Alice would have gone through had all of her nonsensical dreams been steeped in the quotidian reality of her ordinary life. There are no talking birds, no storytelling mock turtles, no dormice living in teacups. In fact, short of a crude cut-out superimposition of a very ordinary looking "Cheshire cat" flying in the sky (a la the Teletubbies' eerily omniscient baby in the sun), there's really no special effects or anything that would evince this one of being the least bit chimerical

that is, unless you know the story of Alice in Wonderland already. Ostensibly, what Miller is doing here is showing us the curious, towheaded girl's "adventures" set in a world where people merely sound like birds and look like supine caterpillars sitting loftily back in their Victorian chairs and wondering aloud, "Who are you?" Imagine Wizard of Oz, but without all the costumes, flying monkeys, and mercurial trees pulling at the heroine's hair.

Suddenly, we along with Alice find ourselves in a land where we were already (that is, of course, if we were a haughty 11-year-old girl wandering lackadaisically through our castellated house in the late 19th century). What we see is the "reality" of the dreamworld of Alice's waking life.

And this is exactly what Miller captures in this version of the epic "children's" tale for stoners and mathematicians. In fact, the only real sense of "dreamland" we can extract from Miller's vision is a kind of proto-Gilliam realm of canted camera angles and unsettling juxtapositions of close-up faces in deep-focus environments (think Brazil or particularly Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas, which clearly owes both its visual and aural style to Mr. Miller). Truthfully, after watching this late 60's stark, black-and-white opus (if ever so disjointed and flawed), one would have to assume that Terry Gilliam took much of his artistic sensibility from what is definitely far more than a simple made-for-TV broadcast.

With a quadrille of British mainstaysPeter Cook as the Mad Hatter, Sir John Gielgud as the Mock Turtle, Alan Bennett as the Mouse, an uncredited Eric Idle, and the King of Hearts himself, Peter SellersJonathan Miller, with lilting, ethereal score by Ravi Shankar, does what no other director has done to date with this timeless urtext: he shows us what would have happened had Alice stayed awake during her infamous tour through dreamland.

PS: If this one doesn't do it for you, try out Czech filmmaker Jan Svankmajer's nightmarish Alice (1988), which must be the most haunting adaptation of Alice's adventures yet put on celluloid.

Made for the BBC's The Wednesday Play television series, Jonathan Miller's take on the subject matter is, as is traditionally the case, a unique one. With a budget approximating nothing more than his usual "taped stage plays" for which he previously gained great renown (think preter-PBS), Miller decided to illustrate what Alice would have gone through had all of her nonsensical dreams been steeped in the quotidian reality of her ordinary life. There are no talking birds, no storytelling mock turtles, no dormice living in teacups. In fact, short of a crude cut-out superimposition of a very ordinary looking "Cheshire cat" flying in the sky (a la the Teletubbies' eerily omniscient baby in the sun), there's really no special effects or anything that would evince this one of being the least bit chimerical

that is, unless you know the story of Alice in Wonderland already. Ostensibly, what Miller is doing here is showing us the curious, towheaded girl's "adventures" set in a world where people merely sound like birds and look like supine caterpillars sitting loftily back in their Victorian chairs and wondering aloud, "Who are you?" Imagine Wizard of Oz, but without all the costumes, flying monkeys, and mercurial trees pulling at the heroine's hair.

Suddenly, we along with Alice find ourselves in a land where we were already (that is, of course, if we were a haughty 11-year-old girl wandering lackadaisically through our castellated house in the late 19th century). What we see is the "reality" of the dreamworld of Alice's waking life.

And this is exactly what Miller captures in this version of the epic "children's" tale for stoners and mathematicians. In fact, the only real sense of "dreamland" we can extract from Miller's vision is a kind of proto-Gilliam realm of canted camera angles and unsettling juxtapositions of close-up faces in deep-focus environments (think Brazil or particularly Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas, which clearly owes both its visual and aural style to Mr. Miller). Truthfully, after watching this late 60's stark, black-and-white opus (if ever so disjointed and flawed), one would have to assume that Terry Gilliam took much of his artistic sensibility from what is definitely far more than a simple made-for-TV broadcast.

With a quadrille of British mainstaysPeter Cook as the Mad Hatter, Sir John Gielgud as the Mock Turtle, Alan Bennett as the Mouse, an uncredited Eric Idle, and the King of Hearts himself, Peter SellersJonathan Miller, with lilting, ethereal score by Ravi Shankar, does what no other director has done to date with this timeless urtext: he shows us what would have happened had Alice stayed awake during her infamous tour through dreamland.

PS: If this one doesn't do it for you, try out Czech filmmaker Jan Svankmajer's nightmarish Alice (1988), which must be the most haunting adaptation of Alice's adventures yet put on celluloid.

Jonathan Miller's version of "Alice In Wonderland" is at times both very beautiful to watch and somehow mildly boring to sit through. Boring perhaps because of the detached performance of Anne-Marie Mallik who plays Alice. Jonathan Miller has Mallik play Alice as a girl who watches her own dream fantasy of 'Wonderland' from the outside of the looking glass rather than someone who has gone through the looking glass. It's almost as if Alice knows that she's dreaming and is able to control her own dreams, yet is somehow bored and barely amused with the dream world she has created. Mallick walks through 'Wonderland' as a somnambulist chaser. Transitions from scene to scene include drowsy dissolves or close ups of Mallick in all of her hair brushed beauty staring away from the camera. Large sections of Mallik's dialog are heard by way of voice over while the other actors work around her silence acting in the gaps.

One of "Alice's" strengths is in the rest of the compiled cast. There are some very good performances, most notably Wilfred Brambell as the White Rabbit, John Gielgud as the Mock Turtle, Peter Cook as the Mad Hatter and Michael Gough as the March Hare and of course, Peter Sellers as the King of Hearts. It's too bad that with the two most brilliant comedic minds of the mid 1960's, that of Peter Sellers and Peter Cook, that more freedom wasn't given to explore the comic possibilities these two could give to the story. But having this comedic freedom was not to be part of Miller's vision. Miller describes on the audio commentary of the DVD his dislike for two ad-libs provided by Cook and Sellers. Apparently because of the tight shooting schedule, there wasn't any time for lengthy re-shoots of the two ad-libs that made it into the final cut. Thank goodness for small compromises, I would hate to think of anything Sellers or Cook did on film that would be lost to the cutting room floor.

Even though Jonathan Miller's artistic resume up until the release of this film could boast of a man steeped in the comedic tradition of the Cambridge Footlights and the ground breaking satirical group 'Beyond The Fringe', his version of "Alice In Wonderland" surprisingly finds itself mostly miles away from humor. However, what it lacks in humor it makes up for in the haunting sitar backing music by Ravi Shankar.

This isn't a bad movie, just terribly frustrating and surprisingly boring at times. The good news is that it's only an hour long. This is a trip you should take; just don't get your hopes up too high.

For fans of Monty Python, look for Eric Idle in the choir near the end of the film. He appears at around the 58-minute mark.

7/10 Clark Richards

One of "Alice's" strengths is in the rest of the compiled cast. There are some very good performances, most notably Wilfred Brambell as the White Rabbit, John Gielgud as the Mock Turtle, Peter Cook as the Mad Hatter and Michael Gough as the March Hare and of course, Peter Sellers as the King of Hearts. It's too bad that with the two most brilliant comedic minds of the mid 1960's, that of Peter Sellers and Peter Cook, that more freedom wasn't given to explore the comic possibilities these two could give to the story. But having this comedic freedom was not to be part of Miller's vision. Miller describes on the audio commentary of the DVD his dislike for two ad-libs provided by Cook and Sellers. Apparently because of the tight shooting schedule, there wasn't any time for lengthy re-shoots of the two ad-libs that made it into the final cut. Thank goodness for small compromises, I would hate to think of anything Sellers or Cook did on film that would be lost to the cutting room floor.

Even though Jonathan Miller's artistic resume up until the release of this film could boast of a man steeped in the comedic tradition of the Cambridge Footlights and the ground breaking satirical group 'Beyond The Fringe', his version of "Alice In Wonderland" surprisingly finds itself mostly miles away from humor. However, what it lacks in humor it makes up for in the haunting sitar backing music by Ravi Shankar.

This isn't a bad movie, just terribly frustrating and surprisingly boring at times. The good news is that it's only an hour long. This is a trip you should take; just don't get your hopes up too high.

For fans of Monty Python, look for Eric Idle in the choir near the end of the film. He appears at around the 58-minute mark.

7/10 Clark Richards

Beautifully filmed in a satiny black & white reminiscent of old photographs, this 1966 BBC adaptation of "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland" may displease purists for its less than conventional, as well as decidedly minimalist, approach. It's not a traditional rendering of Lewis Carroll, and doesn't pretend to be; there are no phantasmagoric sets or actors encased in over-sized costumes or big musical numbers or fancy photographic effects. The Alice of this production is a taciturn, stony-faced girl who is neither frightened nor fascinated by her experiences in Wonderland, which is mostly made up of the interiors and exteriors of old English mansions and houses. But in its unorthodox way, it brings Carroll's text to life in a way I don't recall experiencing in other adaptations of the Alice books.

It's apparent that in creating this alternative Alice, producer-director Jonathan Miller expects you to be already familiar with its source; he's evidently assuming you will recognize what he's chosen to leave in as well as leave out, as well as his re-imagined settings. Only a few of the actors are made to look anything like the characters in the Tenniel drawings, such as Leo McKern as the Duchess or Peter Cook as the Mad Hatter; you're basically on your own when it comes to spotting the White Rabbit or Caterpillar or Frog Footman, all of whom are dressed "normally" in period costumes. (Presenting the Carrollian characters as real people isn't a new idea; I recall a TV adaptation of Alice starring Kate Burton in which Humpty Dumpty was portrayed by an elderly man in a rocking chair.)

By tossing out entire scenes, characters and exchanges that were in the book, Miller gives us a sparer, edgier retelling of the Wonderland story, but doesn't stray too far from the original. Why such a sullen, passive Alice? My guess is, this is supposed to be an Alice who fully realizes that she's in a dream and treats her surroundings accordingly.

And so this Alice (played by a charming Anne-Marie Mallik) sits looking bored and disinterested during the Mad Tea Party. Other productions customarily play this scene with all kinds of manic energy, but in this film, the tea party is deliberately drawn out with long, open rhythms reminiscent of an Antonioni or Resnais film. (Alice's Adventures in Marienbad, anyone?) And seemingly for the first time, while I was listening to the Mad Hatter, the March Hare and the Dormouse prattle away, their nonsense started to make wonderful sense. It's easy enough for an actor to recite lines like, "What day of the month is it?," but here, the performers sound like they really mean what they say (and say what they mean).

That same emphasis on dialogue is apparent in the beach scene with the Mock Turtle, played by Sir John Gielgud, and the Gryphon, played by Malcolm Muggeridge. The Mock Turtle's words never sounded so delightful to me before, and thank goodness Gielgud didn't have to deliver them through some huge Mock Turtle mask. This scene also provides one of the movie's most striking images, of the Mock Turtle, the Gryphon and Alice walking barefoot along the shore, with Gielgud softly singing the "Lobster Quadrille" a cappella.

For those seeking a more conventional book-to-film translation of "Alice," I would suggest the 1972 British movie musical starring Fiona Fullerton, complete with elaborate sets and costumes and velvety color photography and songs. Although it was slammed by the relatively few reviewers who saw it, I thought it nicely conveyed a dreamlike quality of its own, especially in its transitions - I found it much more enjoyable than the 1933 Paramount movie or the 1951 Disney animated feature.

But if you think you've had your fill of Alice movies and TV shows, then I urge you to try this one - I think it makes Lewis Carroll sound fresh all over again. (There's very interesting musical accompaniment by Ravi Shankar.) And for a wonderfully acted movie about the real- life Alice Liddell Hargreaves and Lewis Carroll, I urge you to see "Dreamchild" - but that's another review.

It's apparent that in creating this alternative Alice, producer-director Jonathan Miller expects you to be already familiar with its source; he's evidently assuming you will recognize what he's chosen to leave in as well as leave out, as well as his re-imagined settings. Only a few of the actors are made to look anything like the characters in the Tenniel drawings, such as Leo McKern as the Duchess or Peter Cook as the Mad Hatter; you're basically on your own when it comes to spotting the White Rabbit or Caterpillar or Frog Footman, all of whom are dressed "normally" in period costumes. (Presenting the Carrollian characters as real people isn't a new idea; I recall a TV adaptation of Alice starring Kate Burton in which Humpty Dumpty was portrayed by an elderly man in a rocking chair.)

By tossing out entire scenes, characters and exchanges that were in the book, Miller gives us a sparer, edgier retelling of the Wonderland story, but doesn't stray too far from the original. Why such a sullen, passive Alice? My guess is, this is supposed to be an Alice who fully realizes that she's in a dream and treats her surroundings accordingly.

And so this Alice (played by a charming Anne-Marie Mallik) sits looking bored and disinterested during the Mad Tea Party. Other productions customarily play this scene with all kinds of manic energy, but in this film, the tea party is deliberately drawn out with long, open rhythms reminiscent of an Antonioni or Resnais film. (Alice's Adventures in Marienbad, anyone?) And seemingly for the first time, while I was listening to the Mad Hatter, the March Hare and the Dormouse prattle away, their nonsense started to make wonderful sense. It's easy enough for an actor to recite lines like, "What day of the month is it?," but here, the performers sound like they really mean what they say (and say what they mean).

That same emphasis on dialogue is apparent in the beach scene with the Mock Turtle, played by Sir John Gielgud, and the Gryphon, played by Malcolm Muggeridge. The Mock Turtle's words never sounded so delightful to me before, and thank goodness Gielgud didn't have to deliver them through some huge Mock Turtle mask. This scene also provides one of the movie's most striking images, of the Mock Turtle, the Gryphon and Alice walking barefoot along the shore, with Gielgud softly singing the "Lobster Quadrille" a cappella.

For those seeking a more conventional book-to-film translation of "Alice," I would suggest the 1972 British movie musical starring Fiona Fullerton, complete with elaborate sets and costumes and velvety color photography and songs. Although it was slammed by the relatively few reviewers who saw it, I thought it nicely conveyed a dreamlike quality of its own, especially in its transitions - I found it much more enjoyable than the 1933 Paramount movie or the 1951 Disney animated feature.

But if you think you've had your fill of Alice movies and TV shows, then I urge you to try this one - I think it makes Lewis Carroll sound fresh all over again. (There's very interesting musical accompaniment by Ravi Shankar.) And for a wonderfully acted movie about the real- life Alice Liddell Hargreaves and Lewis Carroll, I urge you to see "Dreamchild" - but that's another review.

Você sabia?

- CuriosidadesMost of this movie was shot with a 9mm camera lens.

- Erros de gravaçãoIn the scenes with the Mock Turtle, his legs are crossed in all the long shots, but in close-up shots, his legs are in a completely different position; without there being enough time to have changed them from one shot and another.

- Cenas durante ou pós-créditosThe end credits use Lewis Carroll's original ink drawings from his handwritten manuscript (called 'Alice's Adventures Under Ground') now in the British Library.

- ConexõesFeatured in The Worlds of Fantasy: The Child Within (2008)

Principais escolhas

Faça login para avaliar e ver a lista de recomendações personalizadas

Detalhes

- Data de lançamento

- País de origem

- Central de atendimento oficial

- Idioma

- Também conhecido como

- Alice in Wonderland

- Locações de filme

- Empresa de produção

- Consulte mais créditos da empresa na IMDbPro

- Tempo de duração

- 1 h 12 min(72 min)

- Cor

- Mixagem de som

- Proporção

- 1.33 : 1

Contribua para esta página

Sugerir uma alteração ou adicionar conteúdo ausente