AVALIAÇÃO DA IMDb

7,2/10

5 mil

SUA AVALIAÇÃO

Um jornalista de televisão está pessoalmente envolvido na violência que ocorre em torno da Convenção Nacional Democrata de 1968.Um jornalista de televisão está pessoalmente envolvido na violência que ocorre em torno da Convenção Nacional Democrata de 1968.Um jornalista de televisão está pessoalmente envolvido na violência que ocorre em torno da Convenção Nacional Democrata de 1968.

- Prêmios

- 2 vitórias e 4 indicações no total

Avaliações em destaque

10jzappa

One of the most truthful moments I've seen in a film in a long time: We hear MLK speaking on TV, a professional cameraman watching. We hear King's immortal words which have resounded through the decades, and when Forster finally speaks, he says, "God, I love shooting on film." Medium Cool is full of moments like this, where we see or hear something that plugs into what we're truly thinking, disconcertingly enough, at times when what we're thinking seems to obviously be something else. In Medium Cool, we respond to these things and, some forty years later, aren't quite sure what's real and what's not. This most head-on and seemingly makeshift of films was released in 1969 to reaction and surmise. Five years before, it would have been deemed unintelligible to the general movie audience. What happened, I suppose, is that by then we'd become so trained by the quick-cutting, idea suggestion and stream of consciousness of concepts in TV commercials that we process more quickly than feature-length movies can move. We get cinematic fast-sketch. And we like movies that recognize our intelligence.

Traditional film narratives pronounce themselves: We know all the main techniques/content and archetypal characters. Haskell Wexler's Medium Cool is one of several movies of the late 1960s and '70s that's conscious of these things about movie audiences, like Seconds, Easy Rider, Mean Streets, Who's That Knocking At My Door, The Graduate, The French Connection, etc. Of the bunch, Medium Cool is probably the most visceral. That may be since Wexler, for most of his career, has been a cinematographer, and so he's conditioned to see a movie pertaining to what's being shown and not shown on-screen more than its dialogue and story.

Wexler fabricates a fictional story about the TV cameraman, his passion, his profession, his girl and her son. There is also documentary footage about the riots during the Democratic convention. There is a chain of conscious scenarios that supposes reality (women taking marksmanship practice, the TV crew confronting black militants). There are fictitious characters in actual documentary scenes and vice versa. The misstep would be to segregate the real-life elements from the made-up. They're all equally meaningful. The National Guard troops are no more real than the love scene, or the artificial collision that ends the film. All the images have significance due to the way they are connected to each other.

Wexler induces our recollection of the zillions of other movies we've seen to import things about his plot that he never elucidates on screen. The essential account of the romance (young professional falls in love with war-widow, eventually obtains companionship of her resentful son) is surely not innovative. If Wexler had formalized it, it would have been commonplace and dull. Rather, he specializes in the emblematic and important features of this histrionic (the boy likes pigeons, the woman is a teacher, the location is Uptown, the time is the Democratic convention, the woman feels more authentic to the cameraman than the model he's living with). And these are the scenes Wexler shoots. The leftovers of the relationship are implicit and never shown, eschewing the often essentially unnecessary 2 on our way from 1 to 3.

And Medium Cool also sees not images but their purpose: Wexler doesn't see the hippie kids in Grant Park as hippie kids. He doesn't see the clothes or the folkways, and he doesn't hear the words. He distinguishes their purpose; they are there completely owing to the National Guard being there, and the opposite. Both sides have a purpose just when they encounter one another. Without the encounter, all you'd have would be the kids, dispersed all over the country, and the guardsmen, dressed in civilian clothes and spending the week on their daily grinds. That's interesting too, but it's not what they are that's significant in this film; it's what they're doing there.

Medium Cool is ultimately so seminal, and engaging, owing to the way Wexler braids all these components together. He has made a nearly consummate model of the movie of its time. Since we are so conscious this is a movie, it feels more pertinent and authentic than the graceful fictitious artifice of most other films, including better ones. This befits the last scene all by itself, that chance event that occurs for no reason at all. Chance events are invariably chance events, not fate, not God's will, not karma, and they never occur for a greater purpose. When we get it, it hit me that it's the first movie collision I've ever seen that we weren't anticipating for five minutes before.

Traditional film narratives pronounce themselves: We know all the main techniques/content and archetypal characters. Haskell Wexler's Medium Cool is one of several movies of the late 1960s and '70s that's conscious of these things about movie audiences, like Seconds, Easy Rider, Mean Streets, Who's That Knocking At My Door, The Graduate, The French Connection, etc. Of the bunch, Medium Cool is probably the most visceral. That may be since Wexler, for most of his career, has been a cinematographer, and so he's conditioned to see a movie pertaining to what's being shown and not shown on-screen more than its dialogue and story.

Wexler fabricates a fictional story about the TV cameraman, his passion, his profession, his girl and her son. There is also documentary footage about the riots during the Democratic convention. There is a chain of conscious scenarios that supposes reality (women taking marksmanship practice, the TV crew confronting black militants). There are fictitious characters in actual documentary scenes and vice versa. The misstep would be to segregate the real-life elements from the made-up. They're all equally meaningful. The National Guard troops are no more real than the love scene, or the artificial collision that ends the film. All the images have significance due to the way they are connected to each other.

Wexler induces our recollection of the zillions of other movies we've seen to import things about his plot that he never elucidates on screen. The essential account of the romance (young professional falls in love with war-widow, eventually obtains companionship of her resentful son) is surely not innovative. If Wexler had formalized it, it would have been commonplace and dull. Rather, he specializes in the emblematic and important features of this histrionic (the boy likes pigeons, the woman is a teacher, the location is Uptown, the time is the Democratic convention, the woman feels more authentic to the cameraman than the model he's living with). And these are the scenes Wexler shoots. The leftovers of the relationship are implicit and never shown, eschewing the often essentially unnecessary 2 on our way from 1 to 3.

And Medium Cool also sees not images but their purpose: Wexler doesn't see the hippie kids in Grant Park as hippie kids. He doesn't see the clothes or the folkways, and he doesn't hear the words. He distinguishes their purpose; they are there completely owing to the National Guard being there, and the opposite. Both sides have a purpose just when they encounter one another. Without the encounter, all you'd have would be the kids, dispersed all over the country, and the guardsmen, dressed in civilian clothes and spending the week on their daily grinds. That's interesting too, but it's not what they are that's significant in this film; it's what they're doing there.

Medium Cool is ultimately so seminal, and engaging, owing to the way Wexler braids all these components together. He has made a nearly consummate model of the movie of its time. Since we are so conscious this is a movie, it feels more pertinent and authentic than the graceful fictitious artifice of most other films, including better ones. This befits the last scene all by itself, that chance event that occurs for no reason at all. Chance events are invariably chance events, not fate, not God's will, not karma, and they never occur for a greater purpose. When we get it, it hit me that it's the first movie collision I've ever seen that we weren't anticipating for five minutes before.

Haskell Wexler, a cinematographer by trade, practically invented the technique invented we know today as "cinema verite" with this striking drama that plays so much like a documentary, you'd never guess it was fiction without being told. It's less a story and more a voyeuristic look into the lives of ordinary people thrust into extraordinary circumstances, in this case reporters who are covering a political convention and other Chicago locals who are just minding their own business when the legendary riots break out at the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

Even more groundbreaking is the approach Wexler takes in framing the film's final scenes. He had ample warning that there would potentially be some unrest at the convention, so he decided to thrust his cast right into the thick of it, sending them to the foyer and front entrance of the Chicago Convention Center and the crew right along to film the events. No one knew exactly what would happen, making this perhaps the most creative and timely piece of "improvised" drama in the history of filmmaking up to this point.

Every documentary filmmaker who chooses to make his/her film about actions and events rather than simply a bunch of talking heads owes a debt to Wexler and his creative team on "Medium Cool".

Even more groundbreaking is the approach Wexler takes in framing the film's final scenes. He had ample warning that there would potentially be some unrest at the convention, so he decided to thrust his cast right into the thick of it, sending them to the foyer and front entrance of the Chicago Convention Center and the crew right along to film the events. No one knew exactly what would happen, making this perhaps the most creative and timely piece of "improvised" drama in the history of filmmaking up to this point.

Every documentary filmmaker who chooses to make his/her film about actions and events rather than simply a bunch of talking heads owes a debt to Wexler and his creative team on "Medium Cool".

A rare directorial outing by all-time great cinematographer Wexler, this is generally acknowledged as the most politically radical film ever produced by a major studio. In freewheeling, semi-improvised, ideologically calculated scene after scene, it depicts an apolitical television cameraman's awakening of consciousness and abandonment of the role of passive observer. The class and race politics are four notches up on any comparable contemporary studio feature, that's for sure - with the surprisingly patient explanation of how 6-o-clock-news ideology oppresses minority communities, leading in to a love affair with a working-class single mother instead of some vanguard hippie, you could even argue that this Americanization of Godard has better ideological legs than the master himself. Sure it meanders a tad, and the stylistics can date, but there's nothing else in any movie ever that compares with the climax, as the actors make their way through actual documentary footage of the 1968 Democratic convention and attendant street battles. I mean, how did such a finely balanced mix of integrated narrative, Euro-tics, American underground film and straight-up documentary even occur to them? And how did they then manage to actually pull it off with honors? Pretty damned impressive.

This is one of the great American movies. The reasons for its obscurity have everything to do with mass consumerism in the late 20th century and nothing to do with its quality. In my opinion this film captures the essence of the late 1960s better than Easy Rider, The Graduate, or any of the other popular films that have come to be associated with that era.

Wexler combines a very European (Italian Neorealist/French New Wave) style with a very American subject matter in a way that comes across as completely natural. It is an art film that plays like watching the evening news.

It is exciting both formally, and culturally: not only does it provide a lasting document of the late 1960s counter-culture in conflict with the aging, square America of the Eisenhower era, it more specifically does a fine job of representing the more general cultural conflict of rural people (here white Appalachians) thrust into the Yankee city environment.

All this, and the movie is fun to watch, not some intellectualized snorefest. It a great movie.

Wexler combines a very European (Italian Neorealist/French New Wave) style with a very American subject matter in a way that comes across as completely natural. It is an art film that plays like watching the evening news.

It is exciting both formally, and culturally: not only does it provide a lasting document of the late 1960s counter-culture in conflict with the aging, square America of the Eisenhower era, it more specifically does a fine job of representing the more general cultural conflict of rural people (here white Appalachians) thrust into the Yankee city environment.

All this, and the movie is fun to watch, not some intellectualized snorefest. It a great movie.

Absorbing, thought provoking and, above all, a unique record of an important "place & time", why "Medium Cool" still fails to gain the attention it deserves remains one of life's great mysteries.

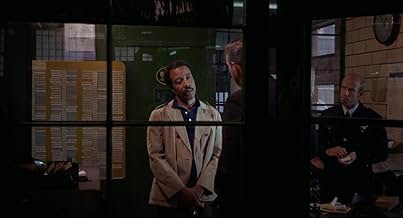

First off, it's a pretty good if somewhat disjointed story two "world-wise" middle class news reporters are sent to film the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago and become unwittingly involved in its political demonstrations, the inner city problems that have precipitated them, and the lives of a single mother and her young son in this harsh, confusing and seriously under-privileged world. Its acting, in particular from Robert Forster as the lead reporter and the 13 year old Harold Blankenship as the son, is excellent and at times so effective that it's difficult to remember you're watching a rigidly sequenced film rather than a social documentary. And, it's overlaid with some quite stunning cinema-photography from director Haskell Wexler, one of America's very best exponents of the art, backed up by a perfectly pitched late 60's soundtrack.

Good enough so far, but that's just the start. Add-in its extensive live footage from the streets of Chicago as the riots develop, taken by the film's camera crew as they themselves are caught-up in a very "real" political drama, its ominous sequencing of the build up of events from a fun "day in the park" for the hippies/yippies to serious "police state" level violence, its equally chilling images of what was going on inside the Convention Hall while all of this was taking place, and the clever and disturbing scenes of the mother's desperate search for her lost son as Wexler films her within the increasingly anarchic crowds of demonstrators & troops actually on the streets at the time, and you've got something very special.

Part film and part documentary, not all of what you think is "real" in "Medium Cool" is, and the lines between live and acted scenes are sometimes confusingly and frustratingly blurred, as in the famous call from one of the camera crew of "look out Haskell this is real" as a tear gas canister lands in front of them, which was in fact over-dubbed afterwards. But that's the whole point of the film as the final, almost startling scenes reveal. How far is the media in control? Is what you're seeing real, distorted or contrived? Wexler's brilliance is to take this underlying theme and to mould it into a fascinating exploration of inner city life, American society in a period of huge change, and the power/needs of the media in a TV dominated world, while, in parallel, producing a gripping record of what it's like to be in the centre of a demonstration that's spiralling out of control. Juxtaposing the impersonality of reporting with the very personal situations that are involved, it raises a whole series of questions on the way without falling into the trap of most films of the era in trying to ram home too many answers. And, as a result, it remains as relevant today as it did then.

Quite rightly regarded as one of the best "counter culture" films of the late 60's and much richer and more thought provoking than this classification usually implies, it remains one of the most under-rated films out there.

First off, it's a pretty good if somewhat disjointed story two "world-wise" middle class news reporters are sent to film the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago and become unwittingly involved in its political demonstrations, the inner city problems that have precipitated them, and the lives of a single mother and her young son in this harsh, confusing and seriously under-privileged world. Its acting, in particular from Robert Forster as the lead reporter and the 13 year old Harold Blankenship as the son, is excellent and at times so effective that it's difficult to remember you're watching a rigidly sequenced film rather than a social documentary. And, it's overlaid with some quite stunning cinema-photography from director Haskell Wexler, one of America's very best exponents of the art, backed up by a perfectly pitched late 60's soundtrack.

Good enough so far, but that's just the start. Add-in its extensive live footage from the streets of Chicago as the riots develop, taken by the film's camera crew as they themselves are caught-up in a very "real" political drama, its ominous sequencing of the build up of events from a fun "day in the park" for the hippies/yippies to serious "police state" level violence, its equally chilling images of what was going on inside the Convention Hall while all of this was taking place, and the clever and disturbing scenes of the mother's desperate search for her lost son as Wexler films her within the increasingly anarchic crowds of demonstrators & troops actually on the streets at the time, and you've got something very special.

Part film and part documentary, not all of what you think is "real" in "Medium Cool" is, and the lines between live and acted scenes are sometimes confusingly and frustratingly blurred, as in the famous call from one of the camera crew of "look out Haskell this is real" as a tear gas canister lands in front of them, which was in fact over-dubbed afterwards. But that's the whole point of the film as the final, almost startling scenes reveal. How far is the media in control? Is what you're seeing real, distorted or contrived? Wexler's brilliance is to take this underlying theme and to mould it into a fascinating exploration of inner city life, American society in a period of huge change, and the power/needs of the media in a TV dominated world, while, in parallel, producing a gripping record of what it's like to be in the centre of a demonstration that's spiralling out of control. Juxtaposing the impersonality of reporting with the very personal situations that are involved, it raises a whole series of questions on the way without falling into the trap of most films of the era in trying to ram home too many answers. And, as a result, it remains as relevant today as it did then.

Quite rightly regarded as one of the best "counter culture" films of the late 60's and much richer and more thought provoking than this classification usually implies, it remains one of the most under-rated films out there.

Você sabia?

- CuriosidadesThe line "Look out, Haskell, it's real!" was actually dubbed in after the shooting. It was supposedly what Haskell Wexler was thinking to himself and he wanted to include it.

- Erros de gravaçãoWhen Eileen enters the L looks for Harold, she is wearing a white hair band, but when they show her sitting on the L, the hair band is missing.

- Citações

John Cassellis: If I gotta be afraid in order for your argument to work, then you got no argument.

- Cenas durante ou pós-créditosStuds Terkel is credited as "Our Man in Chicago".

- Versões alternativasDue to copyright disputes, all video releases feature some different songs on the soundtrack from the theatrical version.

- ConexõesEdited into O Show Não Pode Parar (2002)

- Trilhas sonorasSweet Georgia Brown

by Ben Bernie, Kenneth Casey and Maceo Pinkard

Performed by Brother Bones

Courtesy of Tempo Records

Played during roller derby scene

Principais escolhas

Faça login para avaliar e ver a lista de recomendações personalizadas

- How long is Medium Cool?Fornecido pela Alexa

Detalhes

Bilheteria

- Orçamento

- US$ 800.000 (estimativa)

- Tempo de duração1 hora 51 minutos

- Mixagem de som

- Proporção

- 1.85 : 1

Contribua para esta página

Sugerir uma alteração ou adicionar conteúdo ausente

Principal brecha

By what name was Dias de Fogo (1969) officially released in India in English?

Responda