Um detetive particular assume um caso que o envolve com três criminosos excêntricos, um magnífico mentiroso e sua busca por uma estatueta incomparável.Um detetive particular assume um caso que o envolve com três criminosos excêntricos, um magnífico mentiroso e sua busca por uma estatueta incomparável.Um detetive particular assume um caso que o envolve com três criminosos excêntricos, um magnífico mentiroso e sua busca por uma estatueta incomparável.

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Artistas

- Indicado a 3 Oscars

- 8 vitórias e 4 indicações no total

Charles Drake

- Reporter

- (não creditado)

Chester Gan

- Bit Part

- (não creditado)

Creighton Hale

- Stenographer

- (não creditado)

Robert Homans

- Policeman

- (não creditado)

William Hopper

- Reporter

- (não creditado)

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Elenco e equipe completos

- Produção, bilheteria e muito mais no IMDbPro

Avaliações em destaque

Sam Spade and Miles Archer are detectives, the private type who you can give directives, after meeting with a dame, there then begins a deadly game, with a group who seem to have, their own perspectives; although they all have as their goal a missing falcon, and soon there are some folks, who find their souls gone, as beneath the dark veneer, there are those quite insincere, as you'll find after a number of liaisons; as the story ratchets up the threads combine, and at the centre of the plot's a large waistline, that speaks with eloquence and intent, as deep within, passions ferment, in a film that is a classic of its time.

Great cast, great story, great film - but isn't Sydney Greenstreet outstanding!

Great cast, great story, great film - but isn't Sydney Greenstreet outstanding!

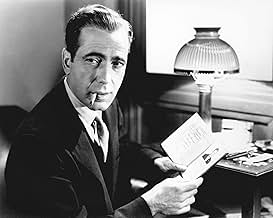

Not only is "The Maltese Falcon" one of the first prototypical examples in what would be the subsequent 10 years of great film noir movies, it's also the first movie in the exemplary directing career of John Huston (from the screenplay he adapted from Dashiell Hammett's Sam Spade novel). And, even though Bogart had been acting throughout the '30s in mostly supporting roles opposite great actors (like Edward G. Robinson, James Cagney, etc.) and actresses (Bette Davis, Ida Lupino, Ann Sheridan, etc.), this role was to make him a bankable star & lead.

Like many films in the noir genre, the unnecessarily complicated plot devices are secondary to lighting, mood, tone, and the imperfect cast of characters. It's not as absolutely inscrutable as "The Big Sleep," but more or less tied with "Out of the Past" on the hard to follow scale. Mary Astor was an old pro by this time, and she'd said that the motion picture newbie, Sydney Greenstreet, was scared to death during his scenes, though you'd certainly never know it from the result.

Huston managed to find a little cameo appearance for his father, Walter Huston as the mysterious Captain Jacoby. And the matte black statuette of the title is perhaps the ultimate example of what Hitchcock called the "MacGuffin," and as Bogart tells his cop friend at the end: "It's what dreams are made of." Indeed.

Like many films in the noir genre, the unnecessarily complicated plot devices are secondary to lighting, mood, tone, and the imperfect cast of characters. It's not as absolutely inscrutable as "The Big Sleep," but more or less tied with "Out of the Past" on the hard to follow scale. Mary Astor was an old pro by this time, and she'd said that the motion picture newbie, Sydney Greenstreet, was scared to death during his scenes, though you'd certainly never know it from the result.

Huston managed to find a little cameo appearance for his father, Walter Huston as the mysterious Captain Jacoby. And the matte black statuette of the title is perhaps the ultimate example of what Hitchcock called the "MacGuffin," and as Bogart tells his cop friend at the end: "It's what dreams are made of." Indeed.

"The Maltese Falcon", scripted and directed by Hollywood first-timer John Huston (from Dashiell Hammett's novel), would go on to become an American film classic. Humphrey Bogart chews the scenery in his star-making turn as acid-tongued private eye Sam Spade, whose association with the beautiful and aloof Brigid O'Shaughnessy (Mary Astor), neurotic Joel Cairo (Peter Lorre), and morbidly obese Kasper Gutman (Sydney Greenstreet, in his Oscar-nominated screen debut) over the recovery of the title object, sets in motion a movie experience that is as much crackling as it is dazzling. While much of the action and dialogue is considerably dated by modern standards, the film's essential power to mystify and entrance remains undiminished despite its age. While this was the third adaptation of Hammett's story (the first was made in 1931 and the second was "Satan Met a Lady" (1936)), this is also the best remembered and most praised, due largely in part to Bogart's seemingly effortless portrayal of the tough but softhearted, world-weary hero. Mary Astor and Lee Patrick were, respectively, the definitive femme fatale and girl Friday, and the villianous roles of Cairo, Gutman and Wilmer (Elisha Cook Jr.) were equally remarkable. What may not be wholly obvious is the fact that these three men have homosexual tendencies (as given in the novel), but just look at what's given: Cairo's delicate speech and manner, Wilmer's questionable quick tempered attitude towards Spade (could this be covering up the fact that he finds Spade attractive?) and Gutman's clutching of Spade's arm when Sam arrives at his hotel room. A polished film noir that gave rise to Bogart's mounting popularity. (Sidenote: The character of Sam Spade was originally offered to George Raft, who turned it down. Raft also turned down "Casablanca" (1942), "High Sierra" (1941) and William Wyler's "Dead End" (1937), all of which went to Bogart and helped to boost his star status. Bogart had Raft to thank for his enduring popularity.) A must-see masterpiece. ****

Humphrey Bogart died nearly fifty years ago, but polls still put him at the top of all-time Hollywood stars. What turns a man into a legend? The man himself wasn't much: a slight build, not too tall, no Stallone muscles to swell his suit. What he had in classic films like `The Maltese Falcon' was a voice that cut through a script like a knife. `The Maltese Falcon,' directed by John Huston in 1941, reprised Dashiell Hammett's thriller. (It had been filmed before.) Hammett practically invented the tough guy so deep in cynicism nobody could hope to put anything past him. The novel, thick with plot, wasn't easy for director John Huston to untangle. Few people who cherish this film can summarize its story in a sentence or two. I'll try. San Francisco private eye Sam Spade (Bogart) is pulled into the search for a fabulously valuable statue by a woman who seeks his help. First, his partner is killed, then Spade pushes through her lies to uncover connections to an effete foreigner (Peter Lorre) and a mysterious kingpin (Sydney Greenstreet). The story unfolds like a crumpled paper. But the whodunit becomes less important than how we respond to the strong screen presence of Bogart and his co-stars. That's what makes `The Maltese Falcon' a classic. We see more and appreciate more each time we watch it. The art of Huston and Bogart doesn't come across until a second or third viewing. Huston invented what the French called film noir, in honor of Hollywood films (often `B' movies, cheap to make, second movies in double features) that took no-name stars into city streets to pit tough guys, often with a vulnerable streak, against dangerous dames. Audiences knew that when the tough guy said, `I'm wise to you, babe,' he'd be dead within a reel or two. Bogart was luckier than most noir heroes, but it cost. Struggling to maintain his own independence against the claims of love or his own penchant towards dishonesty the Bogart hero can do little better than surrender, with a rueful shrug, to the irony his survival depends on. The climax of `The Maltese Falcon' ranks with the last scene of `Casablanca,' another Bogart vehicle, in showing how the tough guy has to put himself back together after his emotions almost get the better of him. That assertion of strength, bowed but not broken, defines the enduring quality of Bogart on screen. For Huston, telling this story posed a different problem. Telling it straight wasn't possible too many twists. Huston chose to focus on characters. One way to appreciate Huston's choices is to LISTEN to the movie. Hear the voices. Notice how in long sequences narrating back story, Huston relies on the exotic accents of his characters to keep us interested. Could we endure the scene in which Greenstreet explains the history of the Maltese falcon unless his clipped, somewhat prissy English accent held our attention? Also, we watch Bogart slip into drug-induced sleep while Greenstreet drones on. Has any director thought of a better way to keep us interested during a long narrative interlude? And is there a bit of wit in our watching Bogart nod off during a scene which, if told straight, would make US doze? All of this leads to the ending, minutes of screen time in which more goes on, gesture by gesture, than a million words could summarize. He loves her, maybe, but he won't be a sucker. The cops come in, and the emotional color shifts to gray, the color of film noir heroes like Bogart. Bars on the elevator door as Brigid descends in police custody foreshadow her fate in the last image of Huston's film. But after the film, we're left with Spade, whom we like and loathe, a man whose sense of justice squares, just this once, with our own, maybe. Black and white morality prevails in a black and white movie, but Sam Spade remains gray and so does our response to this film classic.

I love this movie. I didn't love it until I'd watched it a couple of times.

And I didn't love it quite so much until I'd read Harvey Greenberg's "Movies on Your Mind."

But I now think that, within the strictures of its budget, it's about as good as it can get. Sam Spade is a marvelous character in this film. He gives practically nothing away, while gathering information from others simply by letting them talk, kind of like a shrink.

And it's hard to believe that they could have found a cast that fit the templates of the novel so perfectly. Sidney Greenstreet IS the "fat man." Peter Lorre IS the queer. My nomination for best scene: When Greenstreet attempts to peel off the black enamel from the captured bird and finds that it's nothing but lead and begins to hack away at it, as if it were alive and he were trying to kill it. Nothing is more amusing than a fat man lipid with rage.

If you see this one, and I hope you do, make note of the phenomenal black and white photography. (I hope you have a good connection.) Watch, for instance, the glissade of the camera when Bogart says, "You have brains. Yes, you do."

In case you're worried about this being too sophisticated for enjoyment by an ordinary audience, I should mention that I showed this (in one connection or another, I forget) to a class of Marines at Camp Lejeune. They enjoyed the hell out of it, especially the scene in which Mary Astor kicks Peter Lorre in the shins.

Don't miss it.

And I didn't love it quite so much until I'd read Harvey Greenberg's "Movies on Your Mind."

But I now think that, within the strictures of its budget, it's about as good as it can get. Sam Spade is a marvelous character in this film. He gives practically nothing away, while gathering information from others simply by letting them talk, kind of like a shrink.

And it's hard to believe that they could have found a cast that fit the templates of the novel so perfectly. Sidney Greenstreet IS the "fat man." Peter Lorre IS the queer. My nomination for best scene: When Greenstreet attempts to peel off the black enamel from the captured bird and finds that it's nothing but lead and begins to hack away at it, as if it were alive and he were trying to kill it. Nothing is more amusing than a fat man lipid with rage.

If you see this one, and I hope you do, make note of the phenomenal black and white photography. (I hope you have a good connection.) Watch, for instance, the glissade of the camera when Bogart says, "You have brains. Yes, you do."

In case you're worried about this being too sophisticated for enjoyment by an ordinary audience, I should mention that I showed this (in one connection or another, I forget) to a class of Marines at Camp Lejeune. They enjoyed the hell out of it, especially the scene in which Mary Astor kicks Peter Lorre in the shins.

Don't miss it.

Você sabia?

- CuriosidadesThree of the falcon statuettes made for the production still exist and are conservatively valued at over $1 million each. This makes them some of the most valuable film props ever made; indeed, each is now worth more than three times what the film cost to make.

- Erros de gravaçãoWhen Spade backslaps Cairo, and Peter Lorre's head snaps to the left, he's wearing a polka dot bow tie, but when his head snaps back to the right, his cravat has become striped.

- Citações

Joel Cairo: You always have a very smooth explanation ready.

Sam Spade: What do you want me to do, learn to stutter?

- Versões alternativasAlso available in a computer colorized version.

- ConexõesEdited into Contos da Cripta: You, Murderer (1995)

Principais escolhas

Faça login para avaliar e ver a lista de recomendações personalizadas

Detalhes

- Data de lançamento

- País de origem

- Idioma

- Também conhecido como

- Relíquia Macabra

- Locações de filme

- Bush Street, San Francisco, Califórnia, EUA(death of Miles Archer)

- Empresa de produção

- Consulte mais créditos da empresa na IMDbPro

Bilheteria

- Orçamento

- US$ 375.000 (estimativa)

- Faturamento bruto nos EUA e Canadá

- US$ 18.180

- Faturamento bruto mundial

- US$ 41.740

- Tempo de duração

- 1 h 40 min(100 min)

- Cor

- Proporção

- 1.37 : 1

Contribua para esta página

Sugerir uma alteração ou adicionar conteúdo ausente