AVALIAÇÃO DA IMDb

7,7/10

18 mil

SUA AVALIAÇÃO

A história de uma mulher a quem os preconceitos se separam do marido e do bebê, entrelaçados com outras histórias de intolerância ao longo da história.A história de uma mulher a quem os preconceitos se separam do marido e do bebê, entrelaçados com outras histórias de intolerância ao longo da história.A história de uma mulher a quem os preconceitos se separam do marido e do bebê, entrelaçados com outras histórias de intolerância ao longo da história.

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Artistas

- Prêmios

- 2 vitórias no total

F.A. Turner

- The Dear One's Father

- (as Fred Turner)

Julia Mackley

- Uplifter

- (as Mrs. Arthur Mackley)

John P. McCarthy

- Prison Guard

- (as J.P. McCarthy)

Avaliações em destaque

I first saw this picture as a teenager some thirty years ago. I had no idea what to expect; all I knew was the famous still of Belshazzar's feast which has become one of the best known icons depicting the extravagance of crazy old Hollywood. But I was astounded and bowled over by what I saw. I will make no attempt at a plot synopsis here, since several other reviewers on this site have done so. Most readers already know that Griffith set out to tell four separate stories, laid in four widely spaced historical periods, and that he intercut freely between them, increasing the tempo as the film proceeded, and attempted to bring all four to a climax simultaneously. Clearly he bit off more than he, or anybody, could chew; but the fact that the limits of what cinema could do were being pushed so hard so early is what fascinated me then, and still fascinates me now. I wish to heaven that college film courses would just blow off "Birth of a Nation" and consign it to the oblivion it largely deserves, and show "Intolerance" instead, for this indeed is Griffith's monument, despite its poor state of repair; and at the risk of being technical I would like to address this. I have noticed that the one negative comment running most consistently through the reviews posted on this website is the relative lack of weight given to the French and Judaean sequences relative to the Modern and Babylonian narratives. This is largely the fault of the movie's checkered preservation history. When "Intolerance" failed to make huge sums at the box office, Griffith released the Babylonian and Modern stories as individual features in 1919, reshooting some scenes along the way. He cut up the original negative (gasp!) to do this, and by the time he decided to reassemble the whole movie in 1926, it turned out that all the king's horses and all the king's men couldn't quite put Humpty Dumpty back together again. There was never a shooting script, or a written continuity; Griffith kept the whole thing in his head, and moreover could never stop tinkering with it while it was in release! Consequently, while the Babylonian and Modern stories have survived largely intact, the French and Judaean episodes were depleted by about half. So when we see it now we must recognize that we are viewing a broken sculpture. The movie is a restorer's nightmare; almost a third of its 2000- plus shots exist in variant versions, and the captions were rewritten more than once. But, broken as it is, it's still magnificent. There has never been, and will never again be, anything like it. It has all of Griffith's inconsistencies: subtle and naturalistic acting from Mae Marsh and Robert Harron as the luckless couple in the Modern Story are seen cheek by jowl with outrageous mugging by Walter Long as the Musketeer of the Slums, or Josephine Crowell's Catherine de Medici in France; but no masterpiece on this scale is ever consistent, after all. I love Connie Talmadge's Mountain Girl from Babylon; smart, funny and crazy. Other favorites: Tully Marshall as the villainous Priest of Bel; Seena Owen as the Princess beloved, my personal nomination for Most Fabulous Body of the Hollywood 1910s, never mind the deranged costumes; Alfred Paget as a genuinely humane Belshazzar; Howard Gaye as a believable and totally unforced Jesus. Everything the silent screen of 1916 could do, good, bad, subtle, overblown, crazy or glorious is embodied here; and Griffith never rode so high again. The most satisfactory version currently available, in my opinion, is the Kino on Video edition on vhs and dvd, the one illustrated when you first call the picture up on this site. There are some problems and a few missing bits that I take exception to, but overall this is the version that first time viewers should try.

How on Earth was D.W Griffith able to make this movie back in 1916? Back in the days when the audience were having a hard time focusing on two parallell stories, Griffith gave them four... This is a tremendous spectacle, way ahead of its time, and hardly dated at all. OK, the acting is a little bit over the edge (although Mae Marsh is a personal favourite of mine) and the subtitles are sometimes ridiculous, but the message that this movie brings is absolutely timeless. In fact, this is really the first movie with a vision, an idea. A major influence on Russian director Eisenstein, one has to wonder: Would there have been a Potemkin without this masterpiece? The Birth of a nation is in some ways superior to Intolerance, but for pure strength, innovation and boldness, Intolerance is unsurpassed and unsurpassable. The greatest movie of all times.

I saw a four hour, ten minute version of this as the University of Chicago's Ida Noyes Hall in February, 1993 -- restored with stills and copyright photos, with a new score by Gillian Anderson, featuring the composer conducting the University Symphony Orchestra -- what an experience!

And where, oh where, is this restored version to be seen today?

Somebody get on the copyright owner's case to release the 4:10 version, with Gillian Anderson's score!

This fine film, possibly the quintessential Griffith, has been in the shadow of the notorious Birth of a Nation too long. (Of course, without Birth of a Nation's controversy, this might never have been made). Intolerance has more spectacle than Birth, far more "speaking" parts (if that's not an oxymoron, I don't know what is!), and is far more PC -- but not in a negative way.

See it, in any form you can!

And where, oh where, is this restored version to be seen today?

Somebody get on the copyright owner's case to release the 4:10 version, with Gillian Anderson's score!

This fine film, possibly the quintessential Griffith, has been in the shadow of the notorious Birth of a Nation too long. (Of course, without Birth of a Nation's controversy, this might never have been made). Intolerance has more spectacle than Birth, far more "speaking" parts (if that's not an oxymoron, I don't know what is!), and is far more PC -- but not in a negative way.

See it, in any form you can!

This silent film by director D.W. Griffith is well known to serious movie buffs and historians, but not to today's general public. I doubt that a lot of people these days would have the patience to sit through a film that contained three hours of silence. Nevertheless, the film's technical innovations inspired filmmakers in the 1920's and later, particularly in Russia and Japan. It also inspired filmmakers in the U.S., including Cecil B. DeMille and King Vidor. For this reason, and for other reasons, "Intolerance" is an important film.

The film's four interwoven stories, set in four different historical eras, are tied together thematically by the subject of "intolerance", a word which could be accurately interpreted today as "oppression", "injustice", "hate", "violence", and mankind's general inhumanity.

Griffith's narrative structure, though innovative, is uneven, because he gives more screen time to two of the four stories (the "modern" and the "Babylonian"). Equal time for three stories, thus deleting the fourth, might have worked better.

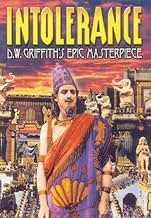

To me, the Babylonian story is the most interesting one because of its more complete coverage, and because of its elaborate costumes and spectacular sets. Even though there is no script, the viewer can easily discern the plot, which suggests that some of today's films might be just as effective, or more so, if screenwriters would downsize the dialogue.

What "Intolerance" offers most of all to contemporary viewers is a sense of perspective. Someone once said that despite the enormous advances in technology, society itself has advanced not at all. That may be true. In the eighty plus years since the film was released, technical advances in film-making have been obvious and impressive. But we are still plagued with the same old human demons of oppression, injustice, hate, violence, and ... intolerance.

The film's four interwoven stories, set in four different historical eras, are tied together thematically by the subject of "intolerance", a word which could be accurately interpreted today as "oppression", "injustice", "hate", "violence", and mankind's general inhumanity.

Griffith's narrative structure, though innovative, is uneven, because he gives more screen time to two of the four stories (the "modern" and the "Babylonian"). Equal time for three stories, thus deleting the fourth, might have worked better.

To me, the Babylonian story is the most interesting one because of its more complete coverage, and because of its elaborate costumes and spectacular sets. Even though there is no script, the viewer can easily discern the plot, which suggests that some of today's films might be just as effective, or more so, if screenwriters would downsize the dialogue.

What "Intolerance" offers most of all to contemporary viewers is a sense of perspective. Someone once said that despite the enormous advances in technology, society itself has advanced not at all. That may be true. In the eighty plus years since the film was released, technical advances in film-making have been obvious and impressive. But we are still plagued with the same old human demons of oppression, injustice, hate, violence, and ... intolerance.

"Intolerance" is D.W. Griffith's apologia for "The Birth of a Nation" mostly in that it surpasses its predecessor's epic scale, thus replying to his critics. "The Birth of a Nation" was a racist film, and nothing in "Intolerance" proves otherwise, but I don't think that's the point, either. And, while Griffith calls his critics hypocrites, it's just as easy to call Griffith one for his racism. Yet, I have no disagreement that his films are art despite their messages. "Intolerance" contains much more agreeable views than "The Birth of a Nation", anyhow: Christian pacifism; support of labor; moderated progressivism; and condemnation of intolerance, hatred and inhumanity throughout the ages.

The narrative structure of "Intolerance" was revolutionary and particularly surprising for a filmmaker who had cemented in cinema a traditional and theatrical form of linear storytelling with his previous work. In "Home, Sweet Home" (1914), Griffith linked four separate stories with a single theme, but with each story told in full before proceeding to the next. With "Intolerance", he employed parallel editing, thus continually crosscutting between time, suspending plots and commenting on stories with other stories, and I think it's ingeniously congruent considering the stories are supposed to run parallel in their morals, or messages on the general theme of intolerance.

The four stories include a modern story, which features a fictional representation of the Ludlow massacre of strikers and a progressive era foundation of busybody reformers that indirectly causes the massacre and directly applies suffering on the central characters. It was originally intended as a complete film in itself and was later released as such under the title "The Mother and the Law". Then, there's the Babylonian story, which was also released by itself, as "The Fall of Babylon". It almost seems to be more likely to have been directed by Cecil B. DeMille than by D.W. Griffith, for all its sex and exotic set design against a historical setting. A contemporary of Griffith, however, DeMille had not yet figured out that formula and may well have been thinking of the Babylonian sequences in "Intolerance" when he did; one of his early pictures and first attempts at an epic, "Joan the Woman" (1917), does demonstrate Griffith's influence on him. Additionally, the sequence features the best performance in the film by ingénue Constance Talmadge as the "Mountain Girl". She, too, seems out of place in a Griffith production, with her sexuality, impropriety and independence. The lesser stories of Christ's life and his crucifixion and the events leading up to the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre aren't especially interesting in themselves, as many have panned. Yet, I don't think that's essential, as they don't stand by themselves, but are part of a whole where they comment on and run parallel to each other and the other narratives.

The stories are connected by explanatory, as well as moralizing and poetical, intertitles and by glimpses of Lillian Gish endlessly rocking the cradle (taken from Walt Whitman). Reportedly, tinting also separated the stories upon initial release. Nearing the climax, however, these separations and transitions evaporate for an ever more merging and rapider plot. "Intolerance" is the apex of Griffith's innovations and developments in editing--the culmination of his achievements in "The Birth of a Nation" and his last-minute-rescue pictures and other Biograph shorts. Along the way, it was usually James and Rose Smith who aided him in the editing room. Doubtless, these achievements, especially in "Intolerance", greatly influenced the Soviet and European montage filmmakers, as well as subsequent filmmaking in general.

With the astounding success of "The Birth of a Nation", Griffith had the opportunity to make almost any film he wanted, and with "Intolerance" having cost nearly $400,000 to make, he did. (The some $100,000 budget for "The Birth of a Nation" had been unheard of in Hollywood.) The film's failure financially ruined Triangle Studios and considerably altered and limited Griffith's filmmaking career from thereon. As "The Birth of a Nation" demonstrated to Hollywood and the world how profitable and popular cinema could be, "Intolerance" told another important lesson on the risks and limitations involved.

Consuming much of the film's budget were Walter L. Hall's Babylon sets, and they are spectacular. They're also surprisingly imaginative and elaborate for D.W. Griffith, whose stagy, open-air sets in previous productions were generally unremarkable--besides those in "Judith of Bethulia" (1914), which pale in comparison. The influence of "Cabiria" (1914) is very evident, but where that film failed to equal the brilliance of its sets with the filming of them, "Intolerance" succeeds. The legendary crane shots are standouts.

Throughout the film, cinematographer "Billy" Bitzer masks the camera lens--more extensively than ever before--creating iris shots, a moving iris shot within a stationary shot and small-scale widescreen effects. Griffith and Bitzer are very much in control of the images, establishing us as spectators. The Babylonian scenes where characters look down at miniatures of the city, I think, also add to this emphasis. And, "Intolerance" is quite a spectacle, especially the Babylonian scenes. Overall, the cinematography, such as some extreme close-ups, is innovative and advanced. Additionally, Griffith and Bitzer once again proved themselves masters of filming battle scenes.

"Cabiria" and the other Italian epics were a great impetus for Griffith to have embarked on his own two epic masterpieces, but the Italian epics were merely super-theatrical, with "Cabiria" as its apex and somewhat of a bridge to Griffith making the epic a cinematic art and a cornerstone of the industry. Moreover, from his pioneering short films at Biograph, to the epics "The Birth of a Nation" and "Intolerance", and to a lesser extent, his work thereafter, nobody has had a greater influence on the course cinema would take than D.W. Griffith.

The narrative structure of "Intolerance" was revolutionary and particularly surprising for a filmmaker who had cemented in cinema a traditional and theatrical form of linear storytelling with his previous work. In "Home, Sweet Home" (1914), Griffith linked four separate stories with a single theme, but with each story told in full before proceeding to the next. With "Intolerance", he employed parallel editing, thus continually crosscutting between time, suspending plots and commenting on stories with other stories, and I think it's ingeniously congruent considering the stories are supposed to run parallel in their morals, or messages on the general theme of intolerance.

The four stories include a modern story, which features a fictional representation of the Ludlow massacre of strikers and a progressive era foundation of busybody reformers that indirectly causes the massacre and directly applies suffering on the central characters. It was originally intended as a complete film in itself and was later released as such under the title "The Mother and the Law". Then, there's the Babylonian story, which was also released by itself, as "The Fall of Babylon". It almost seems to be more likely to have been directed by Cecil B. DeMille than by D.W. Griffith, for all its sex and exotic set design against a historical setting. A contemporary of Griffith, however, DeMille had not yet figured out that formula and may well have been thinking of the Babylonian sequences in "Intolerance" when he did; one of his early pictures and first attempts at an epic, "Joan the Woman" (1917), does demonstrate Griffith's influence on him. Additionally, the sequence features the best performance in the film by ingénue Constance Talmadge as the "Mountain Girl". She, too, seems out of place in a Griffith production, with her sexuality, impropriety and independence. The lesser stories of Christ's life and his crucifixion and the events leading up to the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre aren't especially interesting in themselves, as many have panned. Yet, I don't think that's essential, as they don't stand by themselves, but are part of a whole where they comment on and run parallel to each other and the other narratives.

The stories are connected by explanatory, as well as moralizing and poetical, intertitles and by glimpses of Lillian Gish endlessly rocking the cradle (taken from Walt Whitman). Reportedly, tinting also separated the stories upon initial release. Nearing the climax, however, these separations and transitions evaporate for an ever more merging and rapider plot. "Intolerance" is the apex of Griffith's innovations and developments in editing--the culmination of his achievements in "The Birth of a Nation" and his last-minute-rescue pictures and other Biograph shorts. Along the way, it was usually James and Rose Smith who aided him in the editing room. Doubtless, these achievements, especially in "Intolerance", greatly influenced the Soviet and European montage filmmakers, as well as subsequent filmmaking in general.

With the astounding success of "The Birth of a Nation", Griffith had the opportunity to make almost any film he wanted, and with "Intolerance" having cost nearly $400,000 to make, he did. (The some $100,000 budget for "The Birth of a Nation" had been unheard of in Hollywood.) The film's failure financially ruined Triangle Studios and considerably altered and limited Griffith's filmmaking career from thereon. As "The Birth of a Nation" demonstrated to Hollywood and the world how profitable and popular cinema could be, "Intolerance" told another important lesson on the risks and limitations involved.

Consuming much of the film's budget were Walter L. Hall's Babylon sets, and they are spectacular. They're also surprisingly imaginative and elaborate for D.W. Griffith, whose stagy, open-air sets in previous productions were generally unremarkable--besides those in "Judith of Bethulia" (1914), which pale in comparison. The influence of "Cabiria" (1914) is very evident, but where that film failed to equal the brilliance of its sets with the filming of them, "Intolerance" succeeds. The legendary crane shots are standouts.

Throughout the film, cinematographer "Billy" Bitzer masks the camera lens--more extensively than ever before--creating iris shots, a moving iris shot within a stationary shot and small-scale widescreen effects. Griffith and Bitzer are very much in control of the images, establishing us as spectators. The Babylonian scenes where characters look down at miniatures of the city, I think, also add to this emphasis. And, "Intolerance" is quite a spectacle, especially the Babylonian scenes. Overall, the cinematography, such as some extreme close-ups, is innovative and advanced. Additionally, Griffith and Bitzer once again proved themselves masters of filming battle scenes.

"Cabiria" and the other Italian epics were a great impetus for Griffith to have embarked on his own two epic masterpieces, but the Italian epics were merely super-theatrical, with "Cabiria" as its apex and somewhat of a bridge to Griffith making the epic a cinematic art and a cornerstone of the industry. Moreover, from his pioneering short films at Biograph, to the epics "The Birth of a Nation" and "Intolerance", and to a lesser extent, his work thereafter, nobody has had a greater influence on the course cinema would take than D.W. Griffith.

Você sabia?

- CuriosidadesDuring filming of the battle sequences, many of the extras got so into their characters that they caused real injury to one another. At the end of one shooting day, a total of 60 injuries were treated at the production's hospital tent.

- Erros de gravaçãoOne of the early title cards in the Judean sequence refers to Jesus having been from "the carpenter shop in Bethlehem". Though he was born in Bethlehem, he worked with his father in a carpenter shop in Nazareth, which is why he was known as Jesus of Nazareth.

- Citações

Intertitle: When women cease to attract men, they often turn to reform as a second option.

- Cenas durante ou pós-créditosConstance Talmadge is credited as 'Georgia Pearce' for her performance as Marguerite de Valois in the French Story. She is credited under her own name in the role of The Mountain Girl in the Babylonian Story.

- Versões alternativasThe movie was officially restored in 1989 by Kevin Brownlow and David Gill for Thames Television. It was transferred from the best available 35mm materials, color-tinted per D.W. Griffith's intent, and contains a digitally recorded orchestral score by Carl Davis. This 176-minute version was released on video worldwide, but has never been telecast in the U.S.

- ConexõesEdited into A Queda da Babilonia (1919)

Principais escolhas

Faça login para avaliar e ver a lista de recomendações personalizadas

- How long is Intolerance?Fornecido pela Alexa

Detalhes

Bilheteria

- Orçamento

- US$ 385.907 (estimativa)

- Tempo de duração

- 2 h 43 min(163 min)

- Mixagem de som

- Proporção

- 1.33 : 1

Contribua para esta página

Sugerir uma alteração ou adicionar conteúdo ausente